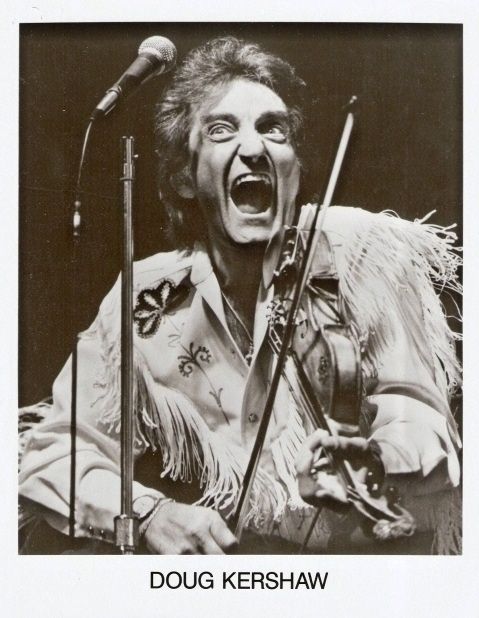

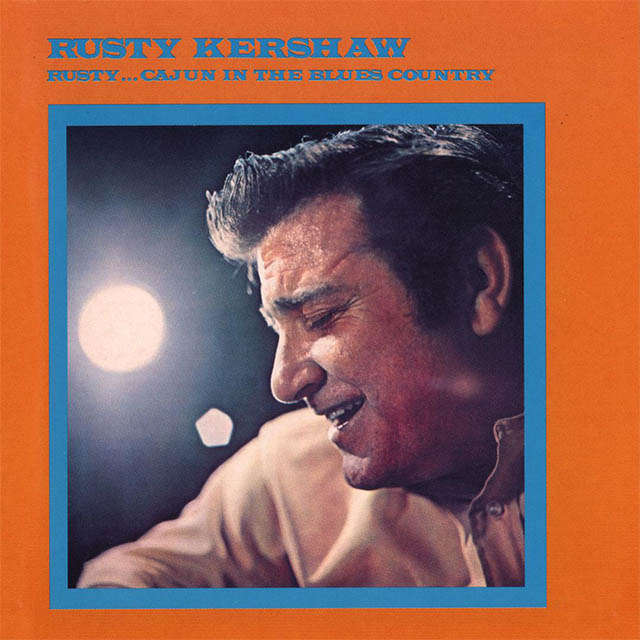

Doug Kershaw is the most famous Cajun musician in history. His brother, Rusty, is not, though you may be more familiar with his work than you realize.

These brothers come from a long tradition of surviving against the odds, against a world that would just as soon see you dead as see you succeed. Starting from nothing but a houseboat in Louisiana, they fought their way through an unscrupulous industry, through honky tonk stages screened off with chicken wire, onto the biggest stages in the business, in order to create some of the greatest music ever made. Then, they battled themselves, their past and their addictions.

Side note: what the hell is “Cajun”? Swamp stuff, right? Well, let’s talk about all of that.

This episode is recommend for fans of: Hardcore History, Neil Young, Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan and discovering unbelievably good music that you’ve never heard.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

In addition to The Library, these books were used for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

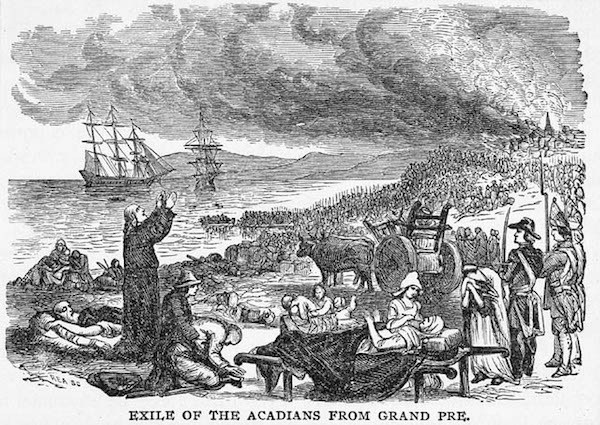

The Grand Derangement

What does the word “Cajun” mean to you? What do you think it means to most people? I think we could ask that question of a hundred different people and get close to a hundred different answers. I can’t tell you what it means but I can tell you where it came from. Or, I can tell you where they came from. Cajuns are people with Acadian ancestors who ended up in Louisiana after being forcibly evicted from eastern Canada by the British in the 1700s, 20 years before the American Revolutionary War. The first Acadians were children of French peasants who, in the early 1600s, colonized the southeastern part of what we today call Canada. It’s worth noting that some percentage of these Acadians were mixed race. Unlike what really happened down by Plymouth Rock, relations between the French settlers and First Nations of Canada, mainly the Mi’kmaq, were actually pretty good. They really did learn local methods of hunting and fishing from the Mi’kmaq. Some of the French men married Mi’kmaq women and started families.

Once trading posts are setup and the Mi’kmaq learn what kind of tools and goods they can acquire by trading furs, it essentially changes the structure of their society. Things seem to be going well. Then, the British Empire begins throwing its weight around. The first capital of Acadia had been established by France in 1605. In 1613, British troops burn it to the ground. During the next hundred years, there are many battles, fought between several nations, over Acadia. By 1713, the British have come out on top but the vast majority of the population is still Acadian and Mi’kmaq. Conflict between Great Britain and France show no sign of calming down, so the British demand an oath of unconditional allegiance from the Acadian people, who, remember,

originally came from France and speak (at least a version of) the French language. But that doesn’t make them inherently unified in allegiance to France or inherently unified in anything, really. Still, for the Acadians to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain could make them obliged in the future to fight for the British against the French or against the Mi’kmaq. That’s a problem. Because, the Mi’kmaq? They aren’t about to concede ownership of their lands to anyone. In fact, they aren’t even aware that France has been claiming ownership of Acadia for a hundred years already. Whether or not it binds the Acadians to take up arms, signing this oath of allegiance to Britain will be viewed by the Mi’kmaq as a betrayal and put Acadian villages at risk of violent raids. So, what the Acadians do here is negotiate an agreement of neutrality with Britain. Their official stance is they just want to stay out of it. Only, some of the Acadians and many Mi’kmaq remain extremely anti-British. Hostilities continue with some regularity over the next 40 years or so, until this all finally comes to a head in what Americans call the French and Indian War, beginning in 1754.

One year into this war, Britain decides there’s really no reason for them to mess with any of this Acadian bullshit. It doesn’t matter who says they’re loyal to Britain or not, who says they’re neutral or not, all the Acadians have to go. British troops round up entire villages, put everyone on boats and ship them off to the 13 British colonies on the east coast of America. In 1758, they begin shipping Acadians all the way over to France and Great Britain. From beginning to end, this process takes about ten years. There were 14,000 Acadians in the area before the first wave of the expulsion. By the year 1764, less than 3,000 are left. And, if this sounds to you like a simple and peaceful relocation of citizens, it is not that. Villages are burned. Families are separated and shipped to different parts of the world on overcrowded ships. Acadians starve to death, drown when ships sink and many of the ones who make it to Great Britain are forced to live in packed warehouses where they die of plague.

Goin’ Down to Louisiana

The British didn’t ship anyone to Louisiana. Among those Acadians who were anti-British from the start was a man named Joseph Broussard. In 1724, when a group of Mi’kmaq attacked the British-occupied capital of Acadia, Joseph Broussard raided alongside them. He fought in and led attacks against the British for the next 40 years until his capture in 1762. The following year, after the war came to an end, Broussard and his family were sent to live in what is now Haiti, then a French territory. By this time, Broussard is in his early 60s and the tropical climate of Haiti doesn’t suit his Acadian constitution. In 1765, he leads a group of 200 Acadians to the Spanish territory of Louisiana. Around 10 months before this, 4 small Acadian families, about 20 people in total, had traveled from Georgia to live in New Orleans. These are the first Acadians to settle in Louisiana.

The Spanish attitude toward the Acadians is super relaxed. They aren’t exactly integrated into mainstream society but they are given land, a six-month supply of food, crop seed, farming supplies and pretty much left alone to pursue their way of life. Nobody cares if they want to keep speaking Acadian French, there are no taxes to pay and the Acadians and Spanish are both predominantly Roman Catholic, which had been one of the big problems between the Acadians and the Protestant English. The Acadians are so comfortable in Louisiana that they write to family members scattered throughout the world to let them know this is a place they can come live in peace. More Acadians make their way to Louisiana.

We can move through the rest of this pretty quickly.

1775: the American Revolutionary War begins. Acadians throughout the colonies take up arms against the British to help The United States gain independence from England. 1803: the Louisiana Purchase brings Louisiana into The United States. Americans move to Louisiana in large numbers to find most of the unclaimed land is swamp and uncleared woodlands. Many Acadians are happy to sell their property for maybe more than it’s worth, move into the backwoods and swamplands, build modest homes and houseboats, get back to hunting and fur trapping as a means of survival, as their ancestors had done. It’s not all of the Acadians doing this and it’s not only Acadians doing this but it comes to be thought of as the Acadian way of life, living off the land in this manner. Over the next hundred years, the way English-speaking Americans say the word “Acadian,” it changes. The Acadian French pronunciation doesn’t emphasize the “a” at the beginning of the word and the “d” probably sounds like a “j” to English ears. What they hear and what they start saying, is “Cajun.”

The early Cajuns wouldn’t necessarily think of themselves as poor. They either have what they need or know how to get it from the land around them and are happy to do so. To people pursuing a more metropolitan way of life, none of that makes any sense. Even other Acadians who stay in the cities take steps to distance themselves from their swampland cousins. As the word “Cajun” begins to take on a derogatory meaning (similar to “hick” or “hillbilly”), more and more of the city Acadians choose to self-identify as Creole instead. The full context of this very ambiguous word is far too complicated to get into here. Suffice to say, in the time and place we’re discussing, it’s seen as classier and more refined to be Creole rather than Cajun, though a strong emphasis on one’s roots is implied by either term. The early Cajuns of Louisiana exist on the outskirts of society and this seems to be, at least partly, a matter of preference. They live in tight-knit communities, which does help to preserve their Acadian traditions, though we only have to look at the language they speak to see how inclusive they are of other cultures. Their version of French borrows elements from Spanish, American Indian and African languages. There would be no cause for this unless these people are a part of the conversation. The weird thing is, when elements of other cultures are co-opted by Cajuns, these things tend to become thought of as Cajun. This is the strength of their culture and how it has survived into the modern age. Cajuns hold on to the past while embracing the present.

Boys in the Band

Some of the earliest Cajun music to be recorded is The Segura Brothers in 1928, doing a song mistakenly labeled as “My Sweetheart Run Away.” Sounds like accordion, triangle, maybe someone tapping their foot a little bit and a voice – that’s it. Admitting that I’m no expert, there is no argument against this being 100% pure Cajun music. If it gets any more Cajun than this, I’m not sure we have a record of it. But the accordion does not come from Acadia and it doesn’t even come from France. Another major instrument in Cajun music is the fiddle. The fiddle comes from neither Acadia nor France and calling it a violin doesn’t make it come from there either. So, two major instruments of Cajun music, neither of which are Cajun, become so in the hands of Cajun players. We could think of this early Cajun music as using whatever instruments are around or easily built to perform in a style handed down from traditional French ballads, which, as we’ve already seen with their language, is a perfectly Cajun thing to do. As in every aspect of the culture, the passing of time sees Cajun music absorbing more elements from nearby genres; country music, in particular, and this one goes both ways. When Cajun music finds mainstream recognition and popularity, it’s on country radio.

Harry Choates’ 1946 recording of the traditional “Jole Blon” is widely regarded as the first hit Cajun song. Probably the most well-known instance of a country musician borrowing from Cajun music is Hank Williams Sr.’s “Jambalaya” in 1952. Some people would say what Hank did there wasn’t so much borrowing from Cajun music as it was lifting the melody of a song called “Grand Texas.” Only, that melody was around for about 20 years before “Grand Texas,” in songs like “Le garcon negligent” by The Guidry Brothers, Happy Fats’ “Gran Prairie,” “Abbeville” by The Jolly Boys and The Louisiana Rounders’ “Allons kooche kooche.” Now, I’ve talked a lot about Western Swing this season, so you may hear some of this music and think it’s just Western Swing with Cajun French vocals. It’s not really that simple because Western Swing is just what happened when country musicians played swing jazz and jazz was practically invented in New Orleans. So, what you’ve got is Texas and Oklahoma borrowing a cup of flour from Louisiana and Louisiana borrowing a cup of sugar from Texas and Oklahoma – it’s all neighborly.

Harry Choates and band

And, all of this, this is how, eventually, in 1969, you end up with Doug Kershaw on TV in the first episode of The Johnny Cash Show, becoming the most famous Cajun musician in history…

You’ll never have a complete understanding of Doug Kershaw until you watch him play. He’s probably the most high energy performer ever associated with country music. I can’t think of anyone else who even comes close and that’s including all the people running around arena stages with pyro going off all over the place. This night, on The Johnny Cash Show, Doug’s wearing a purple crushed velvet suit over a light pink pirate shirt with what looks to be pounds of frilly ruffles exploding out of it. Basically, he’s dressed like Prince a decade before Prince. And, here’s the thing. Johnny Cash is, obviously, a huge star at this time. They gave him his own TV show and this is the first episode. A ton of people are gonna be watching that, no matter what. But, also, Bob Dylan is one of the other guests. In 1966, Bob Dylan used a motorcycle accident that may have never even happened as an excuse to withdraw from public life, bailing on professional obligations, doing no touring and releasing very little of the music he was recording. Even if that wasn’t the situation, he never did and never would do very many performances on television, anyway. So, here, in 1969, when Bob Dylan’s appearance is promoted ahead of time, the word “hype” doesn’t begin to cover it. All of which is to say, Doug Kershaw made the right decision when the show producers gave him a choice. They told him he could have a job playing in the house band for seven shows or he could be featured in a solo spot on one show. He took the solo spot.

A few months later, the Apollo XII astronauts decide their mission control team needs to hear some music and Doug Kershaw becomes one of the first artists to be broadcast from space back to Earth. He’s got a record deal with Warner Brothers. Bob Dylan brings him in the studio to play on some stuff. A pre-Eagles band, called Longbranch Pennywhistle, have Ry Cooder and Doug play on their album. Doug performs at the Newport Folk Festival and spends a week as the opening act for Eric Clapton’s Derek and the Dominos at the Fillmore East. This is all in the year 1969. The rock music world goes head over heels for Doug Kershaw. Circus magazine’s headline reads “Doug Kershaw: Crazy Cajun Fiddler.” He lets his hair grow out some and works up a mean set of mutton chop sideburns to play into the “wild wolf man” image. Audiences eat it up. More TV appearances on Hee Haw, Ed Sullivan, The Dean Martin Show. We’re not talking about a one or two year bump from being on TV once in 1969. Skip ahead to 1973, Doug goes on Midnight Special twice, including the episode with Joe Walsh and Richard Pryor. (Midnight Special will have him back twice more in 1974.) Still in 1973, Loudon Wainwright III releases the album, Attempted Mustache, just after a single called “Dead Skunk” from his previous album accidentally became a Top 20 pop hit. Attempted Mustache opens with “The Swimming Song,” an impossibly addictive song that does not become a pop hit but does become an instant folk music classic. Guess who Loudon brings in to finish up the song? (Hint: it’s Doug Kershaw.)

This isn’t your average overnight success story. Not only because it’s a musician associated with country music crossing over to lasting success with mainstream audiences but also because this isn’t, by any definition of the term, an overnight success story. Doug Kershaw had already sold millions of records with his brother, Rusty, a decade before The Johnny Cash Show. And, while Doug is making these TV show appearances and playing fiddle on big-time recording sessions in Nashville, his brother Rusty is on the other side of the country making one of the most critically acclaimed albums of all time. So, before I can tell you the rest of Doug’s story, before I can tell you Rusty’s story, I have to tell you the story of Rusty & Doug…

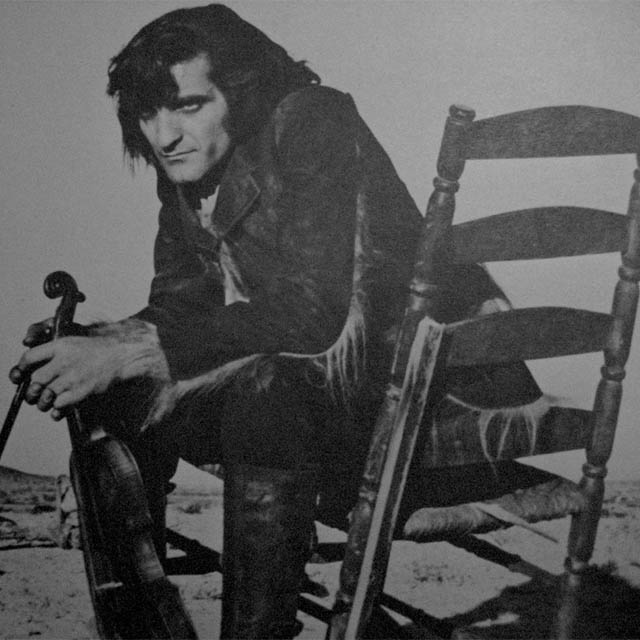

The Cajun Way

Doug Kershaw was born in 1936, the seventh of nine children. His younger brother, Rusty, was born in 1938. And these kids might as well have been born on another planet. They live on a houseboat tied to a tiny island, upstream from the Gulf of Mexico, south of Lake Arthur. Their father’s name is Jack Kershaw. He supports his family by trapping furs, running fishing lines and hunting alligators. Their mother, maiden name Rita Broussard, is a descendant of the Joseph Broussard we heard about earlier. If Cajuns had royalty, we’d be looking at it right now. The Broussards and the Kershaws are intensely musical. Jack plays accordion. Mama Rita plays both guitar and fiddle. Virtually everyone in her family plays at least one instrument. Her brother, Savin, plays several and he’s blind. Doug and Rusty’s older brother, Pee Wee, can play all the instruments their parents play. Doug is five years old when Pee Wee is given a new fiddle. Pee Wee being old enough to go out with Jack every morning to check and run fishing lines, that fiddle gets left on top of a tall cabinet and Doug gets left with strict instructions to leave it alone. When Rita leaves, too, to check and set crab traps, little Doug climbs up there, gets the fiddle down and teaches himself to play by doing what he’s seen everyone else do with the instrument. Until one day, he drops the fiddle and puts a crack in it. Jack’s never whipped Doug before but, when he comes home and sees the damaged fiddle, he tells Doug the only way out of a whipping is if he can play the thing. Doug plays three songs for him. Two of them, he makes up on the spot. This is all according to Doug. There’s no possible way to fact check it and he’s certainly got a reputation for exaggeration but it’s a great story and doesn’t hurt anyone if it isn’t exactly true, so who cares, right? However it happens, he becomes a pro-level fiddle player at a very young age.

In Doug Kershaw’s seventh year on this planet, he finds his father’s body laying on the ground. Jack had shot himself in the head. There are chickens pecking around at what’s left of it until Doug chases them away. As it would anyone, this scene haunts Doug for many years, maybe forever, though he would later say he found peace with his father and became able to understand that Jack had a reason for what he did. What that reason was, I don’t believe Doug ever said. After Jack’s suicide, times get hard for Rita and her children. She moves the entire family in to the town of Lake Arthur and gets a job washing and ironing clothes for 50 cents a day. Doug didn’t have, need or want a pair of shoes until this move to town. He’s so used to sleeping on a houseboat that it takes him weeks to be able to fall asleep in a bed on land. In order to attend school, Doug has to learn how to speak English. Yes, this American swamp baby never learned English because all the family speaks at home is Cajun French. We can assume the same is true for little Rusty.

Doug gets it in his mind to help bring in some money by becoming a shoeshine boy in town. The only problem is he’s too little to fight for a good spot. Working the places that are left, he doesn’t have much luck getting customers until the day he takes his fiddle with him, just to kill time while standing around between shines. Maybe eight years old now, he’s already mastered the instrument. The child prodigy draws a crowd. When he realizes what’s happening, Doug says he’ll only keep playing if some people pay to have their shoes shined between songs. He makes $10.20 that first day and the Kershaws have a new family business. Quickly deciding to cut out the shining shoes part, we soon find Mama Rita onstage at Lake Arthur’s notorious Bucket of Blood, her little boy, Doug, on fiddle beside her. Not “if” but when fights break out, Rita tells Doug to lay down on the stage while he plays so there’s at least a smaller chance he’ll take a direct hit from a flying beer bottle. I don’t know any stories that begin this way and end with that little kid becoming a banker or a doctor or a lawyer. Do you? Typically, a young life put on this road never gets off of it.

Big brother, Pee Wee, has a band of his own until, around the time Doug turns 12, Pee Wee quits that other band, he and Doug start a new band. Doug teaches his little brother, Rusty, to play guitar and The Continental Playboys are in business, playing the stage of every honky tonk that will let a bunch of children inside. You know, the real respectable-type joints. The Continental Playboys mostly perform country music but they sing almost entirely in Cajun French. Their repertoire is built off the jukebox selections around town. This is how Doug explained their early influences in an interview, “When we started playing the bars, we also began to learn the songs off the jukeboxes. We didn’t have a radio or a record player when I was growing up, so jukeboxes were really important to me.” In addition to Cajun music, they would have heard the country greats. like Ernest Tubb and Bob Wills, plus big band stuff by Glenn Miller. Back to Doug: “…and I learned to play it all. I still love to play ‘Stardust.’ You know, there were no labels on the jukebox – it wasn’t country or jazz or Cajun – it was just music.”

Some fans of Cajun music will tell you that Doug and Rusty Kershaw never really made Cajun music. Again, I’m no expert and I don’t really care what anyone wants to call their music but Doug and Rusty Kershaw, the human beings, are as Cajun as it gets. Their approach to music, listening to everything around them and using what they needed from it, that’s Cajun. You’ll even find people out there who say Doug Kershaw isn’t that good of a fiddle player. I gotta give a strong disagree, there, but you don’t have to take my word for it. Michael Doucet is one of the most respected Cajun fiddlers around. In 1975, he was given a grant to study Cajun fiddle under at least five legends of the field. When it comes to Cajun fiddle, he knows what he’s talking about more than I ever will:

I’ve known Doug for 20 years. Some people dismiss him as just a showman who does a lot of crazy things onstage but that’s not the whole story. Don’t forget, he came up the hard way. He was real poor when he was growing up and he played those little bars with the chicken wire around the stages when he was just a kid. The things he sings about in “Louisiana Man” may sound romantic and rural but that’s the story of hard life. You can’t fault him for wanting to have more than that. You know, I’ve played with lots of old-timers and they all have their own rhythm and when I’ve played with Doug, he has it too. It’s an amazing amalgamation of notes, melodies and rhythms that you can’t fake. –Michael Doucet

So, all those wild man stage antics sometimes get in the way of him playing a song as well as he could, sure. This is not classical music. Fiddle, not violin. It’s Doug doing what he learned to do as a small child in honky tonks: entertain the people in the room. The Continental Playboys may have been doing Ernest Tubb songs but, if you could take a time machine back there, I’m certain you’d see Doug dancing around as he played like every song was “Diggy Liggy Lo.”

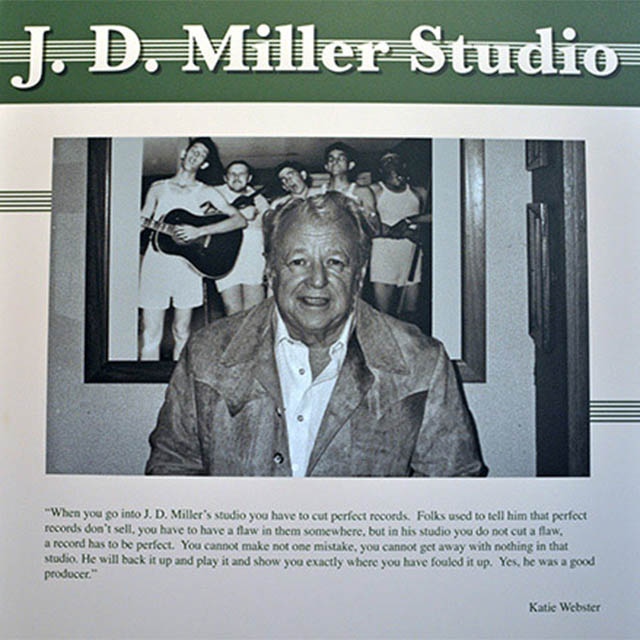

In the Back Room

When Doug is about 15 and Rusty about 13, they leave The Continental Playboys to make music of their own, singing in English, as Rusty & Doug. In Crowley, Louisiana, there’s this guy, named JD Miller. Most people who’ve seen that name were looking at who’s credited with writing Kitty Wells’ “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels.” Miller has a small building that passes for a recording studio in this place and time and a little label he’s calling Feature Records. There’s a picture of a Rusty & Doug recording session in Miller’s studio. Everyone is wearing only underwear because the studio has no air conditioning. It’s so hot and so humid in there, they just strip to record. As far as I can tell, the only Rusty & Doug single to actually be released on Feature is in 1953, called “It’s Better to Be a Has Been Than Be a Never Was.” I think the b-side is a lot better. If you don’t know the term “blood harmony,” then go back and listen to The Louvin Brothers episode of this podcast. It’s one of the most downloaded episodes. I think you’ll like it. At this point, in this story, The Louvin Brothers have already perfected their close harmony style but not very many people have heard it. Rusty and Doug sing in close blood harmony, which you can hear on their first b-side, “No No It’s Not So.”

JD Miller is listed as the only writer on the a-side and a co-writer on the b-side. Here’s the thing about that. One of the songs Doug Kershaw plays on his Johnny Cash Show appearance is “Diggy Liggy Lo.” That song was written by a man called Terry Clement and his brothers. JD Miller is not one of Terry Clement’s brothers but he’s listed as the only writer of “Diggy Liggy Lo” because… Well, because when you’re dealing with a bunch of swamp kids, you make the rules. At no point in my research for this episode did I come across Doug Kershaw talking about ever writing any song with JD Miller. When Doug talks about writing “No No It’s Not So,” it sure seems like he thinks he wrote that by himself. Maybe JD Miller really was the only writer of Rusty & Doug’s first a-side but I’ve got to wonder if him only having half the writing credit on the b-side is why it ended up on the b-side. The one book most people use as a source for info on Miller makes vague references to “royalty disputes” between Miller and the artists he recorded for Feature, while also glossing over the fact that Miller started Reb Rebel records to release non-satirical, non-ironic, white supremacist records by acts like Johnny Rebel. So, I don’t think anyone really has any idea what was going on down there, in Crowley, Louisiana, in the early 1950s or who deserves credit for what.

In any case, Rusty & Doug’s single on Feature goes nowhere. But JD Miller has a connection with Acuff-Rose in Nashville and, in 1954, Acuff-Rose launches Hickory Records. Kind of like the situation we heard about last week between Curb Records and RCA, when Miller finds someone he thinks is good enough, he records them and sends their stuff up to Hickory. If they like it, that artist’s records come out on Hickory with better distribution and promotion. And, you know, it’s pretty weird, but a lot of Rusty & Doug’s records for Hickory in that first year or two have JD Miller listed as a writer, if not the only writer. Miller has a cowrite on their Hickory debut, a song Doug wrote, called “So Lovely Baby,” with piano player Wiley Barkdull singing a prominent bass part. With the Acuff-Rose machine behind them, “So Lovely Baby” goes to #14 on the country chart. We’re in 1955, so Doug’s around 19 years old and Rusty’s about 17. They’ve done a bit of touring and playing with other bands. In 1954, Doug was briefly in Pete Drake’s Atlanta Georgia band, Sons of the South, which somehow also included Jack Greene, Joe South, Jerry Reed and Roger Miller, before any of these people were famous. The success of “So Lovely Baby,” their first hit, leads to Rusty & Doug joining the star-making program, The Louisiana Hayride, from 1955 to 1957. The legendary guitar player, Hank Garland, joins their band for a little while. By 1956, Rusty & Doug are appearing on The World’s Original Jamboree, out of Wheeling, West Virginia, and, in 1957, these young men become members of the Grand Ole Opry. This whole time, their sound is moving around a lot but they’re absolutely nailing everything they try. Around 1956, Rusty & Doug put out a honky tonk number which you could maybe even call an early trucking song, “Going Down the Road.” The song demonstrates a very mature understanding of song structure. These kids may both still be in their teens at this point and the music they’re composing is top-shelf for artists of any age. In 1957, they record the rockabilly-ish “Hey Mae” with Hank Garland on guitar. In the second half of the 1950s, these kids are making it happen. But, just like The Louvin Brothers, just when everything’s getting going good, the war screws up everything.

Rusty & Doug were made members of the Grand Old Opry at the tail end of 1957. I can’t tell if Doug was actually drafted or knew he would be and decided to enlist. Whatever happened, Rusty signs up with him so they can serve at the same time and get it out of the way. While waiting to ship out, both brothers take whatever session work they can find in Nashville. You can hear Rusty playing guitar on an Osborne Brothers song, “There’s a Woman Behind Every Man.” You can hear Doug on Bill Monroe’s recording of a Rusty & Doug composition, “Sally Jo.” His unusual guitar playing is featured in the also quite unusual intro. The Kershaws had recorded more than enough material for Hickory to keep releasing Rusty & Doug singles while they’re in the service but, without them around to tour or play the Opry or do anything at all to promote their records, well, it’s not a good situation.

Fight Your Fight

In the spring of 1957, The Everly Brothers had a #2 pop hit with “Bye Bye Love” and they stayed hot until 1962. As you can imagine, this entire time there is no shortage of close harmony brother acts ripping off the Everly sound. The popularity of that sound may have helped Rusty & Doug get on the Opry (even though Doug would later insist the Everlys had copied their style) but when the Kershaws come back, in the middle of 1960, it’s to a world where Rusty & Doug’s vocal style is no longer very special. Doug remembers sitting on the ground at his apartment, broke, about to be evicted:

I was just coming out of the Army and I was sitting on the stairs writings songs. And all of a sudden I thought: if I could have anything I wanted right now, what would it be? The first thing that popped into my head was not to be ashamed of being a Cajun. See, nobody ever explained that to me when we were growing up. They took our language away. They wouldn’t let us speak French. –Doug Kershaw

He’s talking about what we heard earlier when he started school and had to learn English but he’s also talking about what we heard before that, about the word “Cajun” taking on a derogatory meaning. Since 1921, it was Louisiana law that public education be taught exclusively in the English language. Children who struggled to transition to English from Cajun French were mocked by other students and punished by teachers. Speaking Cajun French in school could get you beaten with a yardstick or worse. By the 1940s, the decade the Kershaw kids moved into town and started going to school, some Cajun parents had completely stopped teaching and speaking their own language to their children so they’d have an easier time assimilating, making kids like Doug and Rusty even more rare, even more singled out for negative attention. Here, in 1960, the only way out Doug can see is to own his Cajun blood, be proud of the people and place he came from, let the world know who and what Doug Kershaw is. Of course, I’m telling you the story of how he came to write the song, “Louisiana Man.” Not as straight of a line from Point A to Point B as you may expect. Hearing the song, not many people would guess that it’s the sound of two boys learning how to accept their own heritage. The pride comes across as fully formed, as if it were always there. When this song comes out in 1961, it’s more than just a hit. Their recording of it only goes to #10 on the country chart but sales and radio play have it 4 spots away from the Billboard Hot 100. It’s estimated to have been covered over 800 times by everyone – just, everyone. Don Rich uses it as an excuse to get his fiddle out on a Buck Owens album. Of course, Jimmy C. Newman crushes it. The Killer kills it. George Jones did it with Gene Pitney. Bobbie Gentry takes it in a pretty weird direction. Bob Luman’s cover is great. And, we can’t forget The Gosdin Brothers. In 1971, Connie Smith’s cover goes to #14. You get the idea. And Doug gets the royalty checks. There’s no telling how many millions of records this song has sold. Of course, a lot of these covers happened after Doug’s 1969 appearance on The Johnny Cash Show but some of them were way before. In fact, it’s quite possible that one cause for Doug’s slingshot resurgence after the TV show is thousands upon thousands of people realizing he not only wrote a song they know and love but that the lyrics are about his life. We’re still years before that, though…

The same day Rusty and Doug record “Louisiana Man,” they lay down a cover of that Clement brothers song, “Diggy Liggy Lo,” and their version of the Cajun traditional, “Jole Blon.” These guys are clearly all-in on getting back to their roots and long before anyone could know how successful it would be for them to do so. When the hype over their recording of “Louisiana Man” begins to calm down, they put out “Diggy Liggy Lo” as a single and it goes to #14. The Kershaw boys are back in the family business. Their final recording session for Hickory gives us “Cajun Joe, The Bully of the Bayou.” Awesome song, not a hit. In 1962, Rusty & Doug move to RCA-Victor to put out “Cajun Stripper,” sung in Cajun French. Because of the title and the fact that, unless you speak Cajun French, you have no idea what they’re singing and whooping and hollering about, it comes off as more than a little dirty. Awesome song, also not a hit. But Rusty & Doug could have toured for decades on “Louisiana Man” & “Diggy Liggy Lo,” alone. Throw in that the live show had to have been incredible and they’re probably set for life. Except, in 1964, Rusty develops a psychological allergy to just about everything you have to do to keep a career in music going. From an interview, done much later:

I just couldn’t stand the grind of tourin’ and the same set every night. I like to play from the top of my head. Once you practice and get all the parts stuck together, that’s what you’ve done – you’re stuck. It takes the life out of it. To me, it’s ‘oh man we gotta play this motherfucker again?’ –Rusty Kershaw

Rusty & Doug are splitsville. Rusty goes back to Louisiana, becomes an electrician and, unfortunately, develops an addiction to uppers and alcohol. The world doesn’t hear much from Rusty over the next five years.

Doug either, because he takes some time to relax, enjoy the success he’s had and think about what he wants to do next. Music being the only answer this guy would ever end up at, in 1968, he goes to Buddy Killen at Tree Publishing Company and says he’s ready to get to work. Buddy Killen is part owner and in-house producer at Tree. At the time, he’s got a great relationship with Warner Brothers. So, he signs Doug to Tree, gets him a deal with Warners and they begin working on Doug’s first solo album. The Cajun Way includes re-recordings of “Jole Blon,” “Louisiana Man” and, if you’ve ever wondered why some people say it one way, other people say it another, “Diggy Liggy Lo” is retitled “Diggy Diggy Lo” this time because that’s how Doug has always sung it. But the song on this album Doug seems to care the most about is a new one he’s written and it’s pretty weird. The title is “You Fight Your Fight and I’ll Fight Me.” He starts off by singing about Napoleon trying to conquer the world and that takes you to the chorus: there’s never been a man alive to live his life and die fully satisfied / I’ve got my problems and I’ve got my good / you’ve got yours and that’s how it should / that’s how it should be, that’s how it should be / you fight your fight and I’ll fight me. The second verse, naturally, is about Hitler: soon come Adolf Hitler / he was to follow Napoleon / the world was his aim, his aim was the world / he would succeed where Bonaparte had failed / France was not first, neither was Spain / Poland was it the Furher had hit. He’s going pretty far out of his way to make these syllables fit the meter and rhyming scheme but the anti-war, “fix your own problems instead of bothering anyone else” message is clear. Then, the last verse kicks off with the line “red man is Indian, white man is what, black man is Negro, yellow is not.” I can’t imagine this is supposed to mean anything except “racism is bad” but I honestly don’t know how these words get us there. Anyway, Doug “fights” for this song to be the first single from The Cajun Way and it does not chart at all. But Johnny Cash has already got on board this train. The Cajun Way’s liner notes are written by Cash and he sets up that appearance on his TV show, launching Doug Kershaw into the mainstream as a solo artist, regardless of the weird first single he chose from his album. The next single is “Diggy Diggy Lo,” followed by “Orange Blossom Special.” You know, fiddle stuff, giving the people what they want and getting all the things we already talked about in return.

Cajun in the Blues Country

In the middle of 1970, Rusty Kershaw comes out of nowhere with an amazing solo album. For some reason, his liner notes are written by a well-known preacher, named Bill D. Campbell, and written terribly but it’s a rare source of information on Rusty’s life. He recaps the success Rusty had as a duo with Doug, then tells us just how bad of an alcoholic Rusty has become since that time. We’re talking two fifths of whiskey a day plus all the amphetamines it takes to stay conscious long enough to drink that. He doesn’t go into details but Rusty messed around and did something that got him put in jail for two weeks, then sent to rehab and, now, he’s back. I’d even go further than to say Rusty is back. He’s better than ever. The album is called Cajun in the Blues Country, which is a clever way of telling you three of the genres combined on the album. I would throw funk in there, too. I don’t want to build it up too much but you’ve got to check it out.

First of all, there’s the session musicians: Weldon Myrick on pedal steel, Gary Scruggs on harmonica, Bob Wilson on piano, Karl Himmel on drums, Tim Drummond on bass, Charlie Daniels on guitar and, naturally, big brother Doug is there to play fiddle and be his producer. Rusty isn’t listed with these guys for doing anything. There’s a picture on the back of him holding an acoustic guitar. I’d be surprised if he didn’t play an instrument or two somewhere on the album but it’s his voice we’re here to talk about because, wow. On the intro to “This Day and Time,” he sounds like Nina Simone. Then, there’s “The Country Boy,” which seems at least semi-autobiographical. It’s the usual story of a country boy going to the big city and getting his head spun around by everything. When he realizes he’s got his own way of doing things, the entire song changes and Rusty gives his full throat to the chorus. In my opinion, this is a very good album but it did not sell very well – which would be tragic, except, if it had and Rusty Kershaw had become a superstar on his own, then he likely wouldn’t have been available to make what I and many other people consider to be the greatest of all Neil Young’s albums.

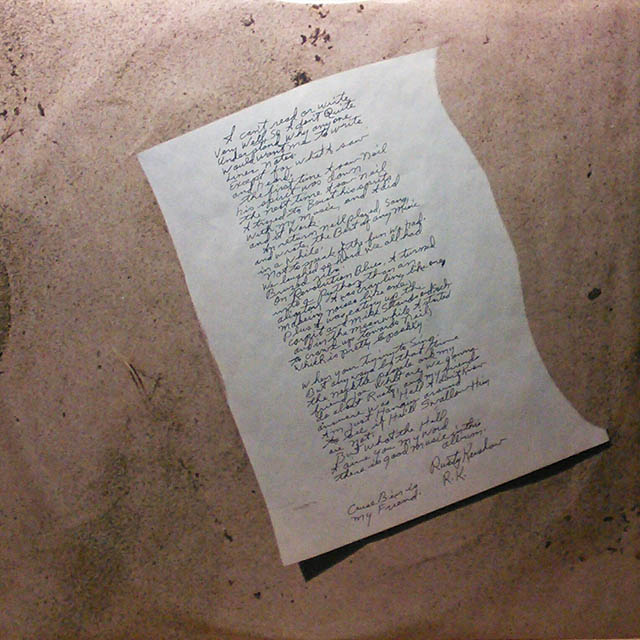

Before we get into this, I want to read you the liner notes Rusty Kershaw wrote for On the Beach because these liner notes are for sure the first experience I ever had with Rusty Kershaw and that’s probably also true for a lot of people reading this. One whole side of the album sleeve is, I assume, a reproduction of Rusty’s handwritten cursive:

I can’t read or write Very Well, so I don’t Quite Understand Why anyone would want me to write liner notes. Except for what I saw and heard. The first time I saw Neil his spirit was down. The next time I saw Neil I tried to Boost his spirits with my music, and I did and it work. In return Neil played, Sang, and wrote, the Best of any Music in a While. Not to speak of the fun we had. We laughed so hard we all had Bruzed ribs. On Revolution Blues, I turned into a Python, than an aligator, I was crawling like one, making noises like one. Plus I was eating up the carpit and mike stands and such. and in the meanwhile I started to crawl up towards Neil, Which is pretty Spooky. When you’re trying to sing. But anyways by that time the necktie people ask my friend Joe What are we gonna do about Rusty, and my friends answer was Hell I don’t know I’m just Hanging around to see if He’ll Swallow Him or not. But what the Hell I give you my word there is good music in this album. –Rusty Kershaw, R.K. Cause Ben is my Friend.

These are truly bizarre liner notes, right? The wildest part is they’re all about to make perfect sense. Now, I’m going to do that thing some of you hate. If you’ve never heard On the Beach, if you’re even slightly curious about it and you can stand to delay the rest of this story, then I would recommend listening to it before finishing this episode and I would recommend being in whatever frame of mind is suggested to you by the cover of the album. On the Beach is not one of those things where you have to know the story of how it was made to appreciate it. Not having any frame of reference for what you’re hearing may even be a huge part of the magic. I really don’t know. It became my favorite Neil Young album the first time I heard it and it has been my favorite since that day. I didn’t know any of the things I’m about to say. Maybe you’ll love it, too. Maybe you’ll hate it. Either way, I suspect the story of how it came into being will make perfect sense to you.

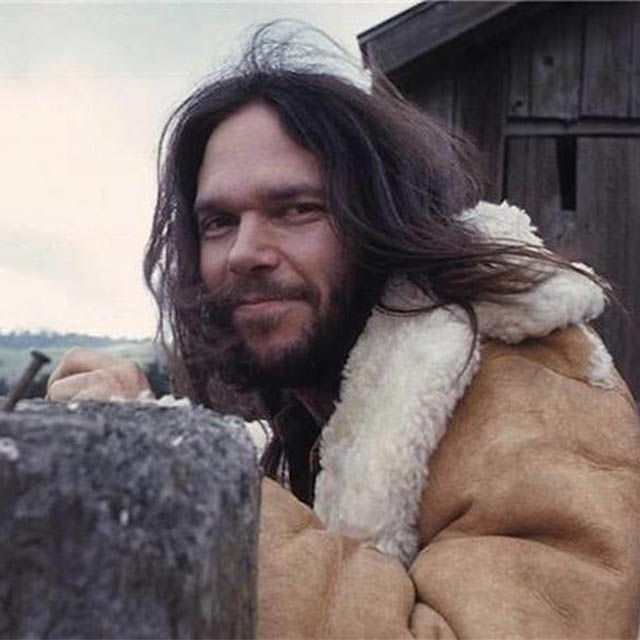

Okay, if you don’t know anything about Neil Young, here’s what you need to know. He was in a very good and successful rock band, called Buffalo Springfield. They broke up and he pursued a solo career, while also joining another great and successful rock band, called Crazy Horse, while also working with David Crosby, Stephen Stills and Graham Nash as Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. In other words, Neil Young is a really big deal. In just a second, he’s going to become the biggest deal. 1971: Neil is in Nashville, Tennessee to perform on The Johnny Cash Show. While here, he meets a local music producer who’s recently opened up his own studio and, funny thing, Neil happens to have already heard and loved the sound of some music recorded in this studio. He’s been planning for a while to do a live acoustic album but, after this serendipitous meeting, he decides he wants to try recording in this studio. And he wants to do it right now, tonight. This producer scrambles to get musicians in there for the session, which, it’s Nashville, so not really an issue. The short-notice pedal steel guitarist ends up being Ben Keith. You’ve heard Ben on Patsy Cline’s “I Fall to Pieces” and you’ve heard him on Neil Young’s Harvest because that’s the album they’re about to start making in this studio. Neil Young is famous for making whatever kind of music he wants to make and not really caring what anyone expects from him. With Harvest, which I would not call straight-up country music but is certainly country-influenced, he accidentally makes 1972’s best selling album in the United States.

So, Neil Young is now the biggest name in American music and he has to go tour his ass off. During rehearsals for one tour, he calls on the other guitarist from that band Crazy Horse to come help out. Neil is super close with this guy. His name is Danny Whitten, he’s a heroin addict and he shows up in very bad shape. Neil tells Danny, who cannot play guitar in his condition, to just go back to L.A. and try to get it together. Later that night, Neil gets a phone call that Danny has died. In an interview from 1975, Neil says, “That blew my mind. Fucking blew my mind. I loved Danny. I felt responsible. And from there, I had to go right out on this huge tour of huge arenas. I was very nervous and… insecure.” You can hear exactly what he’s talking about because there’s a live album from the tour, called Time Fades Away. It was finally issued on CD in 2017, having been out of print since the initial 1973 vinyl pressing. Neil Young calls it the worst album he’s ever made. But Time Fades Away was only released in 1973 because the album he turned in as a followup to Harvest was Tonight’s the Night. Whether a person loves this album or hates it, they would have to agree that it’s a total shitshow. It is the sound of a devastated human being barely hanging on to reality. So, Tonight’s the Night gets put on a shelf, Time Fades Away (approximately 50% as much of a shitshow) is released instead and Neil begins working on his next album.

An Ambulance Can Only Go So Fast

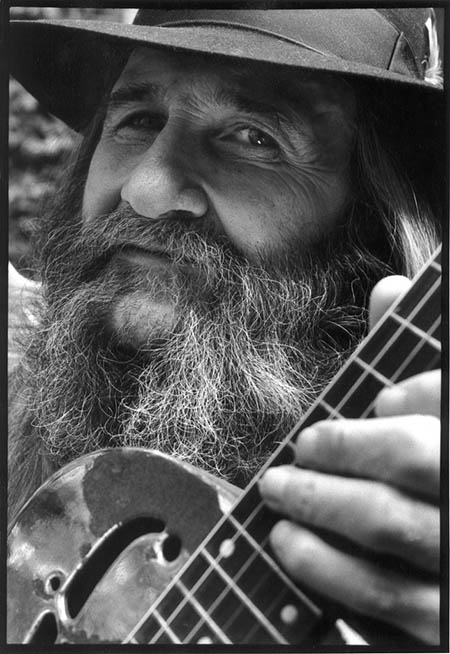

Two of the songs from On the Beach, “Walk On” and “For the Turnstiles,” are recorded with one of Neil’s usual producers, David Briggs. After doing those two songs, David gets really sick and the rest of this album has to happen without him. Other producers are brought in and Ben Keith, that pedal steel player, tries to help out by bringing in Levon Helm and Rick Danko, the drummer and bass player from The Band. Ben also, for some unknown and magical reason, brings in Rusty Kershaw, whom he’d met back in Nashville, sometime around 1956. This crew takes over Sunset Sound Studio and moves in to rooms at the Sunset Marquis Hotel down the street. They only go to the studio to record when inspiration strikes. The rest of the time, they’re just hanging out at this hotel. The list of people stopping by to party at one location or the other is long, including Playboy Bunnies, one of The Everly Brothers and the most famous pornstar in the world, Linda Lovelace.

Rick Danko, Rusty, Jack Good, Doug (1976)

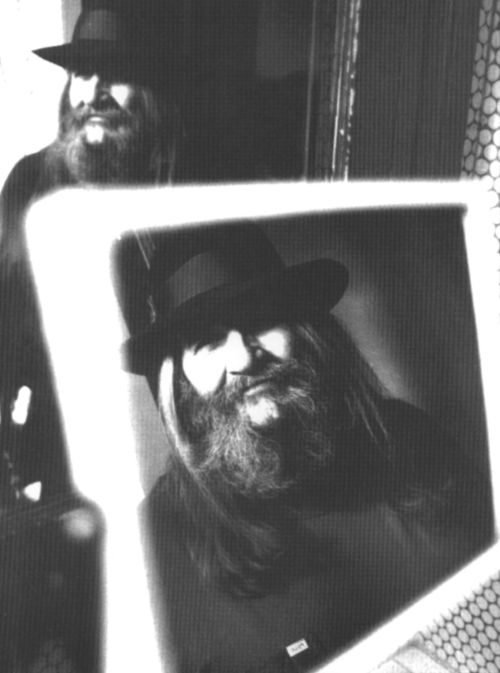

Again, we’re in 1974. It’s about four years after Rusty’s solo album and, if he was sober when he made that, friends, he is no longer. 1970 Rusty was a clean-shaven man with a short pompadour. 1974 Rusty is pretty fat with long, straggly hair and a full swamp beard to match. Tim Drummond, the bassist from Rusty’s 1970 album and Harvest, is here for the On the Beach sessions. He remembers seeing cases of wine and boxes of Fritos being delivered to Rusty’s room. Rusty’s wife, Julie, comes along for the trip and she’s got this recipe for a little treat, called “honey slides.”

It’s just… real poor grade marijuana. Worst you can get on the street… And, you take it and you just get your old lady… If you got one, get her to cook up on the stove… Put that grass in the grinder… Get it real fine, put it in a frying pan, put it on the stove, turn the heat up a little, wait ’til that grass just starts to smoke, just a little bit. Take it off the heat, don’t want to burn it too much. Then you take the honey… Get a half a glass of honey… I hope you ladies are listening, tonight. It’s very important… Just heat that honey right up until it’s slippery… And then mix that grass with it… Take that fine grass that you cooked up… Just ’til it started to smoke and you took it off. Mix those together with a spoon… I think you should eat it after that, yeah. Just eat it after that. Just eat a little of it… Maybe a spoonful or two. You’d be surprised… It just makes you feel fine. –Neil Young

So, the inside scoop with On the Beach is, even if you don’t see his name listed as playing something on a particular song, even if he’s not listed as a producer of anything, Rusty Kershaw is all over everything except those first two songs because he has everyone bombed on honey slides the entire time they’re making this album. Julie Kershaw’s cooking this stuff up by the pound. Ben Keith says, 20 minutes after eating a honey slide, you start forgetting where you are, which, remember, is the very thing Neil Young wants to do at this exact point in his life. Elliott Roberts, Neil’s manager, says, “People passed out. The stuff was like much worse than heroin. Much heavier. Rusty would pour it down your throat and within 10 minutes you were catatonic.” If you haven’t figured out where this is headed, these sessions go way off the rails. Musicians are switched over to instruments they barely know how to play. The shortest song to come out of this is four minutes and four seconds long. The longest and, arguably, best song is nearly nine minutes. Keep in mind, everyone may be losing their shit on honey slides but, for Rusty Kershaw, this is just Monday. Or, who ever even cares what day it is, man? He’s used to this and, as a result, in much better condition than anyone else to take creative control. And that is exactly what he does. If you think I’m playing this up to tell a good story, Neil Young’s own roadie, Willie Hinds, once said On the Beach is Rusty Kershaw’s album, not Neil Young’s.

So, first off, Rusty has no appreciation for the clean look of a professional L.A. recording studio. Right away, they send out for a bunch of old furniture to put in the live room. Neil Young must have really liked this idea because bringing used furniture into recording sessions becomes tradition for him from here on out. A quote from Rusty, “I said ‘shit this is too spiffy. We gotta get this like your livin’ room, man, sitting real close together. Like we’re at home. Either that or let’s put on some suits.’” They get a bunch of easy chairs and lamps. But they mostly leave the lamps off and use candles for lighting. Once the pot and cigarette smoke gets going, nobody in the control room can even see the musicians in the live room; the musicians can barely see themselves or whatever they’re supposed to be doing. Microphones are constantly being knocked away from the source of whatever sound they’re meant to record. Rusty doesn’t play anything on the song “Revolution Blues” but he’s very responsible for the way it sounds, not just because of honey slides. The song is about some killer hippie, Manson family-type shit and Rusty doesn’t think anyone’s playing it like they mean it. Here’s his version of the story…

I said ‘Look man, you don’t sound like you’re trying to start a fuckin’ revolution. Here’s how you start that.’ and I just started breaking a bunch of shit and Ben jumped right in there. I said ‘That’s a revolution muth’ fucker.’ Goddamn that sparked Neil right off. He got it on the next take. –Rusty Kershaw

The next take he’s talking about is when Rusty slithers around on the floor like a snake and all that other stuff from the liner notes. David Crosby plays rhythm guitar on the song and Graham Nash is there, too. Rusty has both of them freaked way the fuck out. There’s one story that may or may not be total bullshit about Rusty pulling a knife on Stephen Stills for trying to take an acoustic guitar out of his hands. According to Julie Kershaw, Rusty goes six weeks without a real night’s sleep. The carpet in his hotel room gets all kinds of red wine stains and cigarette burns from Rusty nodding off. He finally passes out for real one day, after using his pocket knife to stab a note into the outside of his hotel room door. The note just says: DON’T.

As for the parts Rusty actually plays on the album, he’s got his own ideas about how that should go down, too. For one thing, he refuses to practice any song ahead of time. Next, he insists on being as physically close to Neil as possible while recording.

Rusty’s on to that thing. He wants to get that moment – just sit down and ‘I’ll start, then you start goin and we’ll get it’. Some people, once they discover that, they’re so into it that it’s all-encompassing. Nothing else matters. Rusty’s one of ‘em. I was too at one point. He’s a cool cat. Rusty’s fine. He’s wild, boy. –Neil Young

I said ‘Neil, when it’ll move me the most is the first time you play it. You’re gonna do it your very best then – and I can play it with you the first time. We only have to sit real close together.’ Neil said to me later ‘How in the hell do you know how to play this thing the first time I play it? You don’t know what I’m gonna do.’ I said ‘Neil, you carry a heavy vibe and if I’m sittin’ close to you, I can feel what you feel before you play. I know where you’re gonna go.’ –Rusty Kershaw

With how much control he has over everything and people even going so far as to say it’s really a Rusty Kershaw album, it may come as a surprise to learn that he only plays on two songs. They are the final two songs on the album, “Motion Pictures” and “Ambulance Blues.”

Rusty remembers how “Motion Pictures” came together. “Me and Ben and Neil were sittin’ in Ben’s room. Neil started hummin’ something and I started playin’ along with the melody on the steel. Ben started playin’ bass, it sounded so goddamn pretty. Neil picked up a pen and just wrote the words right then.” They went down to the studio and “put that motherfucker down while it was still smeared all over us.” In the album sleeve, “Motion Pictures” has “For Carrie” written in parentheses next to it. That’s Neil’s wife at the time, the actress Carrie Snodgress, whom we heard Neil falling in love with in “A Man Needs a Maid” on Harvest. “Motion Pictures” seems to be Neil’s promise to somehow pull himself out of this crippling depression and make the relationship work again. They divorced soon after this album came out.

Carrie Snodgress, Neil and the caretaker of his ranch

Neil Young says On the Beach is probably one of the most depressing albums he’s ever made but he also says, “Good album. One side of it particularly – the side with ‘Ambulance Blues,’ ‘Motion Pictures’ and ‘On the Beach.’ ‘Ambulance Blues’ – it’s out there. It’s a great take.” Several critics have called this the single best song Neil Young has ever written or recorded. The song prominently features Rusty’s fiddle. Someone could write an entire book about the song “Ambulance Blues.” I would be surprised if nobody ever does. The possible meanings, the historical and cultural references are seemingly endless. If I had to give one meaning to it, I guess I’d say it’s about how attractive nostalgia for the past becomes when the present keeps taking itself away from you. It feels like entering another person’s dream to witness them giving themselves an exorcism.

After they get everything they can get out of the Sunset Strip scene, Neil takes Rusty and a few others out to his ranch for some more recording but these sessions are cut short when word comes in that Carrie Snodgress is headed home after being gone for a while. Neil kicks everyone off the property so he can have privacy to try and save his marriage. After a couple of months playing ringleader for this circus, Rusty Kershaw is out of the picture. At least, until about 20 years later, in 1992, when he decides to make another solo album and asks Ben and Neil to play on it. This is as Neil is in the middle of making Harvest Moon at his ranch, so he invites Rusty to bring his tapes out and record there. Now it’s Neil’s turn to refuse to learn any songs and go for that “natural” first take. Rusty’s album is called Now & Then. His vocals have shifted into Leon Russell territory and I’d expect most fans of On the Beach to enjoy it. Some people say “Future Song” almost feels like a sequel to “Ambulance Blues.”

Rusty Kershaw died of a heart attack in 2001, two days after playing his last show.

Swamp Grass

We left Doug Kershaw back in 1974, still riding that second wave he caught on The Johnny Cash Show.

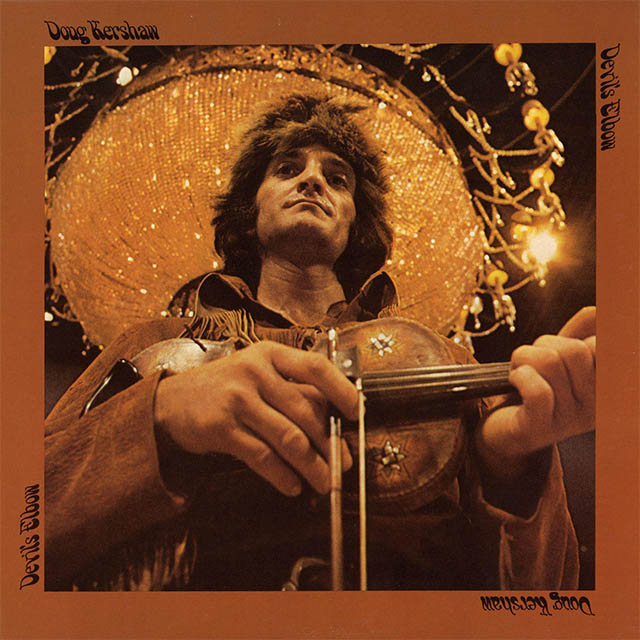

He kept it going for a while but Rusty wasn’t the only Kershaw with a taste for drugs and alcohol. Buddy Killen produced Doug’s albums for nine more years after that first one. In his autobiography, Buddy calls Doug the most difficult artist he ever worked with. Now, the thing about Buddy is he writes about smoking pot like it’s mainlining heroin. He doesn’t go into much detail but weed may have been all Doug was messing with in the beginning. And, yeah, Doug sounds like a pain in the ass in the studio, thinking he’s enough of a big shot to show up late, not listen to anyone, keep engineers there too long – annoying but not that crazy. And he wouldn’t even necessarily have to be stoned to do any of that stuff. There are teetotalers who did every bit of that. Honestly, I’ve got to ask if Buddy Killen should ever have been producing Doug Kershaw in the first place. The albums are good, through the ’70s, even into the ’80s, and they sell well enough, too. But Buddy Killen is a slick Nashville guy and Doug Kershaw is very much not that. Take one of his best albums from the ’70s, Devil’s Elbow. It’s great but I can’t help but wonder how it would sound if Buddy wasn’t treating Doug like some Nashville singer. I mean, he literally uses The Jordanaires on him. Go back a couple albums before this and you’re at Doug Kershaw’s self-titled from 1971. I like the song “Mama Said Yeah.” It’s funky, it’s Doug Kershaw but, then, Jordanaires. Buddy Killen was incredibly talented at what he did. What Doug Kershaw does just happens to be a different thing. As his relationship with drugs moves over to uppers, his behavior in the studio grows more erratic, his working relationship with Buddy worsens until Buddy eventually quits.

Todd Rundgren has a story about meeting Doug around this time. It’s another one that sounds to me like Doug Kershaw just being Doug Kershaw. He could have been 100% sober when this happened but, here you go, make up your own mind. Todd Rundgren is responding to a question about his relationship with Ringo Starr. He says their first time working together…

…a Jerry Lewis telethon in the late ’70s in Las Vegas. Ringo was still something of a drinker at the time. I didn’t really notice. He seemed to be in pleasant spirits. Jerry brought in this fiddle player named Doug Kershaw and made us play behind him and he started playing “Jambalaya” and wouldn’t stop. I got up on one of the drum risers and started directing and we just started playing the song faster and faster until the fiddle player couldn’t keep up any more. That’s the way we made him stop. –Todd Rundgren

In 1978, The Rolling Stones ask Doug to open a show in Dallas. They end up calling him back to the dressing room before the show to jam on “Far Away Eyes.” You can see and hear Doug joining them for that song on the live DVD and album of this concert. It’s not Doug’s fault but it’s one of the worst things I’ve ever heard. Also in 1978, Doug Kershaw has a bit part in Terence Malick’s Days of Heaven. You can spot him in the campfire scene with a bowler hat and some amazing facial hair. In 1981, he moves to the Scotti Bros. label for his album, Instant Hero. The album cover is hilarious. Doug’s basically wearing a Superman costume and he doesn’t look too sure about it. As goofy as the cover is, the album gives him the biggest single of his solo career, a song nobody would ever have expected from Doug Kershaw, “Hello Woman.” It goes #29 country, which, yes, is his biggest solo hit in America. Something else from 1981 is, for some reason, the Dukes of Hazzard TV show soundtrack album has Doug Kershaw all over it. Unless you count the “Hazzard County Boys” backing band, Doug has more songs than anyone else on the soundtrack. I’m guessing this happened because John Schneider, a.k.a. Bo Duke, also has a record deal with Scotti Bros and the soundtrack is on that label. If this is after Doug’s hit with “Hello Woman,” then the label would want to use him as much as they can. Not gonna lie, the soundtrack is pretty good. Check out “Keep Between Them Ditches.”

In 1984, Doug found sobriety. When asked about it, he once said, “I’m more consistent now. I don’t create as much as I used to but I’d rather not create if that’s what it’s going to take. It wasn’t fun anymore. I’m a lot more focused now. I know what I’m doing. I’m paying attention. It may not be as good of a show but I’m playing better than ever before.” As is so often the case, we can safely assume Doug’s substance abuse was part of a battle with depression. Tanya Tucker has a book, called 100 Ways to Beat the Blues, where she got a bunch of different people to relate their experiences with depression. Here’s part of Doug’s section:

When I feel a sadness come upon me, and it still does at times when I’m not paying attention, I’ll take my fiddle out and close my eyes. Then, I just go back in my mind and let the music flow. I think of Mama Rita playing her guitar and singing Jole Blon. Or Daddy jack steering the “going out” boat with his feet so he could save his hands to play the accordion […] When I do this, when I slip back in time to recapture those good, if fleeting, childhood moments – the sounds and colors of all those faisdodos – I feel like – how should I say it? Light. Yeah, that’s it. I feel LIGHT. My mind drifts upward, almost leaving my physical body behind. For a second there, it’s as if I’ve never been judged or criticized or hurt. It’s as if I could never do anything wrong. I feel love, is what I feel. Then it’s over and I’m gone from that old time and place. I’m back in the now time. I don’t dwell on the past, I just plug into it from time to time out of respect for those loved ones who are now gone. And I think that’s the secret. If I were to linger, the blues would hit me like a truck doing ninety miles an hour. So, my advice is this: learn to play the damn fiddle! –Doug Kershaw

As of the night I’m recording this, Doug Kershaw is still performing. Go see him.

Thank you for listening to (and reading) Cocaine & Rhinestones. Every episode of the podcast is written and produced by me, Tyler Mahan Coe.

Every episode, I ask you to share what you just read with one person in your life – friend, a coworker, someone you meet at a party who seems like they might be interested. This week, that mission is going to be very easy. All you have to do is find a Neil Young fan. There’s a good chance they either don’t know much about how On the Beach was made or don’t know all this other stuff about Rusty Kershaw and his brother, Doug.

Next week on the podcast, it’s the final regular episode of the first season and I’m going to be talking about Ralph Mooney. That’s a name too few people know and it’s been my experience that most of the people who do know it don’t even know all the reasons they should know it. It’s going to be another episode with a ton of fantastic music in it and I hope you’ll love it.

-TMC

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [linked, if available]:

- Doug Kershaw – “Mama Said Yeah” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Segura Brothers – “My Sweetheart Run Away” (real title: “La Valse de Bayou Teche”) [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Harry Choates – “Jole Blon” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Hank Williams – “Jambalaya (On the Bayou)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Guidry Brothers – “Le garcon negligent” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Happy Fats & Rayne-Bo Ramblers – “Gran prairie” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Jolly Boys – “Abbeville” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louisiana Rounders – “Alons kooche kooche” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Chuck Guillory & His Rhythm Boys – “Gran Texas” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Doug Kershaw – “Diggy Diggy Lo” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bob Dylan – “I Threw It All Away” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Loudon Wainwright III – “The Swimming Song” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty & Doug – “My Uncle Abel” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Glenn Miller – “Stardust” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty & Doug – “It’s Better to Be a Has Been Than to Be a Never Was” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty & Doug – “No No It’s Not So” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Terry Clement & His Rhythmic Five – “Diggy Diggy Lo” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty & Doug – “So Lovely Baby” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty & Doug – “Going Down the Road” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty & Doug – “Hey Mae” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Osborne Brothers – “There’s a Woman Behind Every Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bill Monroe – “Sally Jo” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Everly Brothers – “Bye Bye Love” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty & Doug – “Louisiana Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Don Rich (Buck Owens & His Buckaroos) – “Louisiana Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jimmy C. Newman – “Louisiana Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jerry Lee Lewis – “Louisiana Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones & Gene Pitney – “Louisiana Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Louisiana Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bob Luman – “Louisiana Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Gosdin Brothers – “Louisiana Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Connie Smith – “Louisiana Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty & Doug – “Diggy Diggy Lo” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty & Doug – “Cajun Joe (The Bully of the Bayou)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty & Doug – “Cajun Stripper” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Doug Kershaw – “You Fight Your Fight and I’ll Fight Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty Kershaw – “Keep on Trying” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty Kershaw – “This Day and Time” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty Kershaw – “The Country Boy” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Buffalo Springfield – “Mr. Soul” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Neil Young with Crazy Horse – “Come On Baby Let’s Go Downtown” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Crosby Still Nash & Young – “Helpless” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Neil Young – “The Needle and the Damage Done” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Neil Young – “Out on the Weekend” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Neil Young – “Yonder Stands the Sinner” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Neil Young – “Roll Another Number for the Road” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Neil Young – “Revolution Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Neil Young – “Motion Pictures” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Neil Young – “A Man Needs a Maid” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Neil Young – “Ambulance Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty Kershaw – “Future Song” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Doug Kershaw – “Jamestown Ferry” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Doug Kershaw – “Hello Woman” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Doug Kershaw – “Keep Between Them Ditches” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rusty & Doug – “Why Cry for You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Excerpted Video

These may be removed from YouTube in the future (for any of a number of reasons) but, for now, here they are:

Commentary and Remaining Sources

Okay, I’ve talked about my personal connection to a few episodes and everyone seems to like it a lot when I do that. So, I’m going to do that again in these Liner Notes but it may take a while because, whether or not it means anything of consequence or it’s merely some kink in human perception of causality, I think coincidence is one of the most interesting things in life and, for me, it’s off the charts, here.

I can’t remember if the first instrument I wanted to play as a child was drums or fiddle. (We’re talking six or seven years old.) I never got good at either. In fact, I never even got a drum kit. But I did get a fiddle and I took some lessons, played at a school recital, all that stuff. I still have that fiddle, mostly because Doug Kershaw scratched his name into it for me. I don’t know why. It’s not something I would have asked him to do unless an adult told me to ask. But he did it and that was nice of him and I would surely also have been enamored with his playing and performing style – so I’ve always liked Doug Kershaw. Not that I’ve always listened to him a lot and own every album or anything but, you know, the idea of Doug Kershaw, like the idea of that person who you think of as your best friend even though you haven’t talked to them in five years. Like that. So when you grow up and then become as obsessed with movies as you are music and you’re going through the Terence Malick films and Doug Kershaw pops up in Days of Heaven, it feels like seeing that best friend. When you later become obsessed with this weird folk song about swimming to the point that you put it on realize for hours at a time while you’re doing other things, only to realize nearly a decade later that the Cajun yell you always assumed was Loudon Wainwright III is actually Doug Kershaw – that one’s a little weird but also cool.

Then, in 2003, On the Beach was issued on CD, having been out-of-print since the vinyl release, similar to Time Fades Away. I used to go to music stores and buy albums based on nothing but the cover. My thinking was, hey, if the people who made this music think this album cover is cool and I also think it’s cool, well, we’ve already got that in common, so maybe the music’s good. There was a display for On the Beach. I liked the cover. I bought it and it immediately blew my mind. There isn’t another album in the world that sounds this way. And, you know, considering the fact it’s a miracle they didn’t burn the recording studio down making it, there’s a great reason for that. And, by the way, I know some Neil Young fans want to argue with me about which one of his albums is more of a shitshow. Listen, I don’t care. That’s not a conversation that’s interesting to me. Time Fades Away wasn’t shelved. On the Beach wasn’t shelved. Tonight’s the Night was shelved. I didn’t write that story, I’m just telling it. But, like I said, I didn’t know anything about it when I first heard On the Beach. It was just the music that got me. The liner notes, I probably read a couple of times, tried to make sense of them, you know, couldn’t and then forgot about. Definitely didn’t even think twice about the last name, Kershaw, and never thought to look into it because the rest of the album packaging gives no indication of how important Rusty was to it. He only plays on two songs. They had him write the liner notes. Whatever.

It was only when reading Shakey, Jimmy McDonough’s biography of Neil Young, that all of this came together for me. It’s an incredible book. If every famous musician had a book like this written about them, then reading those books would be everyone’s favorite hobby and there would be no reason for this podcast to exist. There’s a pretty crazy story here, too. Neil Young is big on documenting everything in his life, so he brings Jimmy on board to write his authorized biography, which takes about eight years of interviews with Neil and everyone who’d been around him. Then, Neil Young decides he doesn’t want the book published and Jimmy has to sue to get it published. So, I think you should read Shakey as soon as you can. It covers everything, from the beginning nearly up until the year 2000. Most of the “making of On the Beach” stuff came from there. The interviews Jimmy did with Rusty Kershaw are amazing. In answering one question, Rusty mentions how he used to be in a country music act with his brother, Doug, and a 10,000 watt lightbulb goes off in my head. All of these things, everything I’ve been talking to you about, become 100 times more interesting and, pretty soon, I’m consumed with discovering as much as I can about, well, all of the things I told you in the episode and even more personal connections that I have to the story.

In researching the episode, I came across an old Kurt Vile interview from nearly ten years ago where he talks about how much his father played Rusty & Doug’s music when he was little. Kurt also says that his own favorite artist biography may be Shakey, so it’s possible Kurt is in a somewhat similar boat with me on this one.

One thing about Danny Whitten’s overdose, it wasn’t heroin and it may have been an accident. He took Valium for arthritis in his knee and he was drinking a lot to try and kick heroin. That’s a classic recipe for an accidental overdose. It may have been a suicidal overdose but it wasn’t with heroin.

While we’re talking about drugs, I could see some people here in 2018 thinking all these stories about honey slides must be full of exaggeration – these guys were all stoner musicians already and they must have had a high tolerance, etc. Well, for one thing, smoking pot and eating it are two extremely different experiences. The other important fact to remember is that this is in the middle of the 1970s. Hell, we’re in 2018 right now and my friend told me a horror story about overdoing it on legal edibles in California last week. So, yeah, I think it’s safe to say these guys were all tripping their faces off.

The Stephen Stills story is that Rusty and Neil are playing together, it’s starting to sound good and Stills must think he’s got an idea for something Rusty should be doing with his part because he goes to take the guitar away from Rusty without asking and Rusty freaks out, pulls a knife on him, etc. Rusty says Neil was telling him to “go ahead” and “do it.” Neil doesn’t remember this happening at all, so I have no idea if it did happen or not.

Some of you may have heard rumors about Rusty Kershaw doing animal sacrifices in his hotel room. I don’t believe this happened. It would not surprise me to learn that Rusty started the rumors himself just to mess with people but it’s easy to see how they could have started on their own. Ben Keith’s lawyer did have to get Ben and Rusty out of some trouble for destroying a hotel room. Standard. Rusty’s “otherness” in being Cajun also comes into play. Then, you’ve got Rusty’s particular brand of humor. He’s got a story about a groupie he was with one time who told him all about some sexual encounters she had with a monkey. Whether or not it’s true, Rusty thinks that story is great. Throw in the rest of his behavior, the knife in the hotel room door, the honey slide filter over everything and, boom, animal sacrifice rumors.

This is a good place to jump into the Cajun stuff. I think many people don’t realize it because, “oh, we love the food and the music,” but, even today, the word “Cajun” can be used in a derogatory way and can come with a stigma attached to it. To say it as plainly as possible, they are a product of ethnic cleansing. Cajuns descend from a displaced people. Doug Kershaw remembers needing to use the bathroom when he was a little boy in segregated Louisiana. The bathrooms were labeled WHITE and COLORED. Doug didn’t know which one he was supposed to use. I don’t know how I could ever begin to understand that or relate to that. But one thing that always bothers me is when the issue of race in country music finds its way into the mainstream news cycle for, you know, two days before everyone goes back to not being a sudden expert on the topic. First, they act like it’s only white people and black people who ever made country music and, second, most of them act like Charley Pride is the only black person who was ever embraced by country music. Half of these articles spell Charley Pride’s name wrong, which should be a pretty good indicator of what we’re dealing with, here. Yes, it would be ridiculous to pretend that there has not been racism and whitewashing in country music. Just as it is ridiculous to pretend there has not been racism and whitewashing in every genre of music that is popular in America. Just as it is ridiculous that every piece like this fails to acknowledge the Mexican artists, American Indian artists, every black artist whose name isn’t “Charley,” Cajun artists and artists from every other culture who did and do play a role in this music. When these journalists do this, they’re committing the exact crime of omission that they’re accusing country music of committing. This is a topic I broached last week with The Judds because it tied into another false narrative about authenticity and because I knew today I’d be talking about Cajuns in country music. These are enormous conversations. They are difficult conversations but they are historical conversations and I intend to continue instigating them.

Speaking of recognizing other cultures and their contributions to country music, Doug Kershaw’s re-recording of “Diggy Liggy Lo” went to #1 in Canada, where country music has always been huge.

I’ll link all the online articles and interviews below but I did want to mention one website, in particular, which is earlycajunmusic.blogspot.com. Whoever made that website is awesome. That’s how I was able to build the partial timeline of the melody that ended up in “Jambalaya” by Hank Williams.

I could see some people wondering how I can defend Buck Owen’s business practices and then talk about how JD Miller took credit for the work of the artists he recorded. I could see some people wondering how I can say “Okie from Muskogee” was satire or Shelby Singleton’s pro-segregation records were just a cash grab and then call JD Miller’s Reb Rebel a white supremacist record label without allowing for these motives to enter into it. Well, these are very clearly different things and there should be no confusion of them as equal. There’s a world of difference between Buck Owens entering into standard negotiations with professional songwriters to receive a percentage of publishing on their songs when he records them and JD Miller putting himself down as the writer of songs that were really written by a bunch of kids who don’t know the first thing about the music business and English isn’t even their first language.

Most of my information on JD Miller came from the book, South to Louisiana by John Broven, which has a lot of great information in it but really does let Miller present a highly sanitized version of what he was doing with Reb Rebel records. It’s not possible to have the full discussion that needs to be had without saying a word that nobody reading this signed up to read when they started this episode, so I can’t get all the way into it, here. But, suffice to say, the author of this book didn’t make Miller get into it either, letting him speak only about the least inflammatory of the material he produced and letting him present his segregationist philosophy as if that represented the beliefs of most white and black people in Louisiana pretty much uncontested. There’s even a story here from an artist named Happy Fats that has to be total bullshit about a van load of black people flagging him down on the road to buy 15 copies of his pro-segregation song because, according to him, the black people of Louisiana liked things segregated and wanted it to stay that way. JD Miller speaking out about being pro-segregation means there’s no possibility of these songs being viewed as satire or a cash grab. But, also, the pro-segregation material is hardly the beginning of the problem, here. I don’t see how I could ever bring myself to use one second of a Johnny Rebel song on this podcast but if I did, then you would immediately understand how much of a difference there is between a satirical song about racism or even a sincerely pro-segregation song and what I would call a hate crime in the form of a song. Again, it’s not something that can be completely unpacked right here and right now but I have a deeply personal loathing for these recordings.

The other book on the music of this area, Swamp Pop by Shane K. Bernard, doesn’t even mention the fact that Miller started Reb Rebel but it does at least call him out for not being the real writer of “Diggy Liggy Lo.”