Ralph Mooney is one of the most important individuals in the history of country music. A legendary pedal steel guitarist, he deserves the reputation he earned on his instrument. However, he deserves a lot more than that. Moon played a major role in upgrading the sound of the entire genre on no less than three separate occasions.

This episode of the podcast backtracks to Bakersfield for a deeper examination of its “sound,” a closer look at some people responsible for it and the story of a man whose story isn’t told nearly often enough. It would be unacceptable to end the first season of a podcast on the history of country music without dedicating an episode to Ralph Mooney. After today, you’ll know why that is.

This episode is recommended for fans of: honky tonk music, the Bakersfield Sound, steel guitar, Wynn Stewart, Waylon Jennings, Ray Price, The Maddox Brothers and Rose, Buck Owens, Merle Haggard, Marty Robbins, Skeets McDonald and road stories.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

In addition to The Library, these books were used for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

Back to Bakersfield

Let’s back up a bit.

In the tenth episode of Cocaine & Rhinestones, we talked about a song because Buck Owens played lead guitar on it. I’ve seen it called the first song with the Bakersfield Sound on it. What is the Bakersfield Sound? Where did it come from?

One guy playing on the song is named Bill Woods. He’s known as the Father of the Bakersfield Sound but that’s less because of his great piano playing and more because of the patriarchal role he served in Bakersfield’s music community. In Bakersfield’s heyday, he led the most popular house band in town, The Orange Blossom Playboys. The musicians he hired were simply the best. Everyone knew it and many of the players who did come to define the Bakersfield Sound came through that band. One of them was Buck Owens. We could argue all day long about what the Bakersfield Sound even is, so I would be a jackass to stand here and tell you any one person invented it. When I talk about the Bakersfield Sound, I’m talking about a style of music performance and a style of music production that Buck Owens made famous and where it went from there – twangy telecaster guitar parts with a high-end tone that could slice right through an AM radio signal, a whirlwind of whining pedal steel guitars and crying fiddles coming in and out of the mix. Oh, and you can take that tube compressor and throw it in the trash because we will not be squashing the dynamics in our tracks, thank you very much. No, not even on the drums. If he hits the kick harder at the end of the verse that’s because it’s supposed to be louder there. In fact, since we have stereo now, pan that all the way into one channel and let the reverb live on the other side. Yeah, sounds good. In other words, this is electric honky tonk music, born out of having to play a blend of several musical genres through awful sound systems for rowdy crowds in loud dive bars. And you don’t have to do anything special in the studio to make it sound good except get out of the way because the people in that room playing those instruments do this for hours, every single day.

If we go back and listen to the rest of that “first Bakersfield Sound” song, we hear that it’s just Western Swing. We begin to wonder if people who say it’s the first song with this sound on it, maybe what they mean is the people responsible for the song. It’s a Sheb Wooley song, done by Bud Hobbs & His Trail Herders. Those “Trail Herders” are Bill Woods & The Orange Blossom Playboys. At the time, that means Bill Woods on piano, Big Roy Lee on bass, Oscar Whittington and Jelly Sanders on fiddle, Tommy Collins on guitar, Johnny Cuviello on drums and Dusty Rhodes on steel. It’s plain as day, these guys can shred some Western Swing. But, then, for less than 15 seconds, Buck Owens’ guitar comes in and, oh – that’s probably what people mean when they say this is the first song with the Bakersfield Sound on it because there it is, right there. Again, I’m not saying Buck Owens gave birth to the Bakersfield Sound but he was damn sure in the delivery room and he made that baby a star. Even if you do think Buck Owens is the walking, talking definition of the Bakersfield Sound, you’ve got to add a lot more than Western Swing to him to get it. Even if you think Buck Owens is the devil and the other guys playing on that session or any of 100 other individuals deserve all the credit, well, they were all listening to and playing the same things. Buck Owens is more famous than any of them and we have much more information on him and his influences. So it doesn’t really matter who we think deserves the credit, if we’re trying to dig up some roots of the Bakersfield Sound, the easiest way is by looking at Buck Owens’ influences.

One time, Merle Haggard said Wynn Stewart’s sound is what influenced him and Buck Owens both. Merle calls Wynn Stewart’s sound the basis of “the West Coast sound.” Now, this is going to piss some people off but under no circumstances, by any definition, was Merle Haggard involved in creating the Bakersfield Sound. His early records sound like they were made in Nashville by the same people producing Marty Robbins. Honestly, at the beginning of his career, he was just a few steps removed from being a Marty Robbins impersonator. There is nothing wrong with that. Marty Robbins is phenomenal. Merle Haggard is phenomenal. But it is a world apart. All of that being said, go listen to Wynn Stewart’s first single, “I’ve Waited a Lifetime.” It came out in 1954, the same year Buck Owens played lead guitar on that Bud Hobbs song, and you absolutely can hear Wynn Stewart’s influence in the music Buck Owens would go on to make, as well as the entirety of anything you want to call the Bakersfield Sound.

So it appears we’re on the right track, here, looking at Buck Owens’ influences. Among many others, here’s who else we’ll find behind this door: Jimmy Bryant, Roy Nichols, Skeets McDonald, Jack Guthrie and The Maddox Brothers with Rose.

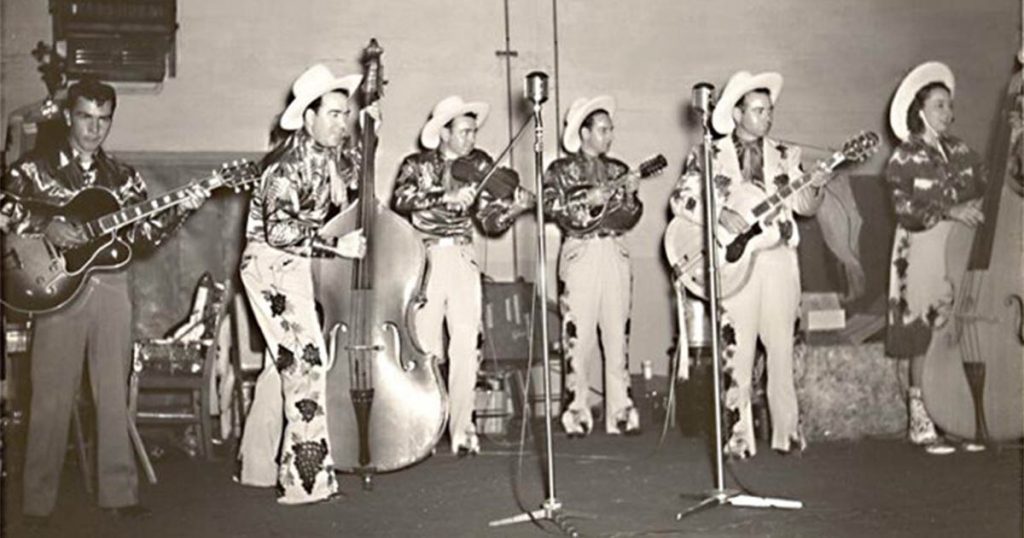

From 1937 to 1956, The Maddox Brothers with Rose made the rowdiest hillbilly music ever recorded. Maybe rock & roll, rockabilly and punk music would have happened if The Maddox Brothers with Rose never existed. Maybe. But they influenced everyone making honky tonk music on the west coast, played and sang like they were jacked up on trucker speed, took flashy western wear to a new extreme and introduced Roy Nichols’ lightning hot guitar playing to the world. From 1948 to 1950, Roy Nichols was in the studio and on the road with The Maddox Brothers. They hired him when he was only 15 years old because he was already that good. Little Buck and Bonnie Owens saw Roy play with The Maddox Brothers and Rose at a stop in Mesa, Arizona. Roy spent 1953 in Lefty Frizzell’s band, which is when a teenaged Merle Haggard saw him play for the first time.

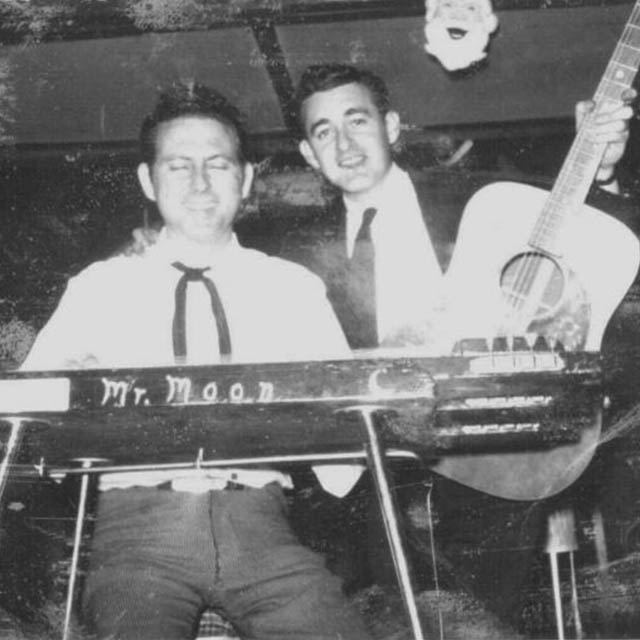

Roy Nichols (left) with The Maddox Brothers & Rose

From 1950 to 1956, Jimmy Bryant was Ken Nelson’s favorite guitar player for session work at Capitol Records. His playing style is a big influence on Buck Owens. Jimmy and his partner, pedal steel guitarist Speedy West, were popular enough to release recordings under their own names, while also playing on hundreds of sides for other artists, like Tennessee Ernie Ford and Sheb Wooley. It’s all great stuff but, apparently, Jimmy Bryant wasn’t the easiest guy to deal with. When Buck Owens came around with his professional work ethic, Ken Nelson started calling Jimmy less and Buck more. We already heard the rest of that story. It includes Buck Owens becoming an iconically successful artist after Capitol Records finally let him control what happened in his own recording session. One of the players on that session was a man Buck refers to in his autobiography as “the great Ralph Mooney.” What’s important to understand, here, is Buck isn’t calling him that because it’s 40 years later and he’s writing his memoirs after everyone went on to make history. Mooney played on every one of Buck’s first seven Top 10 singles but that’s not why he’s calling him great, either. Buck Owens thought of him as “the great Ralph Mooney” right there, in that very first session, because, there, in 1959, Moon was already a part of country music history. See, several years before this, a little song that Ralph wrote came out and instantly altered the course of country music in the second half of the 1950s. And Ralph Mooney’s work in Wynn Stewart’s band is, just as much as anyone or anything else, a main ingredient of the Bakersfield Sound. Somehow, despite all of that, Moon is most well-known for being Waylon Jennings’ pedal steel player in the ’70s and ’80s. Well, today, I’m here to tell you why we’d still be talking about Ralph Mooney if Waylon Jennings had never been born.

Mr. Moon

Ralph Mooney was born in 1928, in Oklahoma. At the age of 12, he moved to California to live with his older sister and her husband. It looks like this brother-in-law is who taught Ralph how to play guitar, fiddle and mandolin. Then, Ralph heard a steel guitar. There’s no telling how many kids tried to imitate the sound of Leon McAuliffe playing “Steel Guitar Rag.” Hopefully most of them didn’t use a knife, which is what Ralph did.

After learning about pedal steel guitars, Ralph built his own out of wooden planks, steel rods and coat hangers. If you’ve never seen a pedal steel in action, it’s a little difficult to explain. A steel guitar is pretty much a guitar built into a tabletop with the strings raised up real high and open-tuned, so you can slide a solid metal bar over them for a unique sound. That becomes a pedal steel guitar when you install a bunch of pedals and levers for your feet and knees to bend certain strings up or down while you play. To anyone who doesn’t play one, it looks like witchcraft but, to fans of country music, it sounds like heaven. This is one of the instruments that critics of the Nashville Sound say was missing from the pop country coming out of Music City starting in the late ’50s. Of course, what they were really used to hearing were the much older and twangier sounds of non-pedal steel and dobro. Pedal steel guitar wasn’t recorded in country music until 1949 when Speedy West played one on Eddie Kirk’s “Candy Kisses.” Eddie was big on the Los Angeles scene, so Ralph Mooney may very well have heard Speedy playing on that song as soon as it came out. Most people will tell you it wasn’t until 1954, when Bud Isaacs played one on Webb Pierce’s “Slowly,” that pedal steel replaced non-pedal steel as the standard in country music. But, way before that, Speedy’s pedal steel guitar, along with Jimmy Bryant’s electric guitar, were signature elements of country, rockabilly and pop songs coming out of L.A.

From 1949 on, Ralph Mooney and everyone else on the West Coast were hearing pedal steel on records by artists like Johnny Horton, Sheb Wooley and Tennessee Ernie Ford. Working from these great influences and his experience on other instruments, Ralph found his way around that homemade pedal steel. And it may not have been lovely to look at but Leo Fender would eventually ask to borrow it to study the design, giving him in return a Fender pedal steel guitar to play on tour.

Ralph’s first band gets hired by a neighbor to play a gig, which leads to more gigs and, pretty soon, Mooney is in the house band of the popular Squeakin’ Deacon radio show in L.A. This is where Ralph Mooney meets Wynn Stewart. The year is 1950. Mooney’s about 22 years old and Wynn is around 16. Here’s how Ralph remembers it, “Wynn and his dad would come in every Sunday to this talent contest that Squeakin’ Deacon held at the Compton Ballroom. He was called ‘Winford’ then. He won that talent contest every time. People hated to see him come in. You’d win a wristwatch and he would come in and show off this arm full of wristwatches.” Winford is winning so many talent shows that he starts going by Win Stewart around the time Mooney begins playing in his band. For the rest of his career, no matter who he’s playing with, Ralph Mooney thinks of himself as Wynn Stewart’s steel player.

Ralph Mooney & Wynn Stewart

In 1954, Wynn gets his first record deal with a little indie label. What’s interesting is Moon remembers playing lead guitar on the session for “I’ve Waited a Lifetime.” Listen to the instrumental break and you can hear the beginning of what we think of as Mooney’s signature sound in the lead guitar. Having played guitar longer, it makes sense that he’d develop his style there and move it over to the pedal steel. The same year, he plays steel on a Terry Fell session for “Get Aboard My Wagon.” It’s a pretty typical steel part. So he isn’t really “Moon” yet but he’s a good steel player and the session work keeps coming in. If you run through some of his pedal steel parts over the next five years, you can hear the progression of his style and how quickly he found a unique voice. Again, the first Wynn Stewart song and the Terry Fell song are 1954. So you could check out Skeets McDonald “Strollin” (1955), rockabilly singer Glen Glenn a.k.a. Glenn Trout “A Hundred Years from Now” (1956), Skeets McDonald again, on a song Mooney helped write, “Keep Her Off Your Mind”(1957), Wanda Jackson “Honey Bop” (1958), brilliant interplay with Wynn Stewart’s vocal on the chorus of “Wishful Thinking” (1959) and, by 1960, Ralph Mooney is such a respected pedal steel guitarist that he’s going in the studio for himself to cut instrumental covers of popular songs, like Eddie Miller’s “Release Me.”

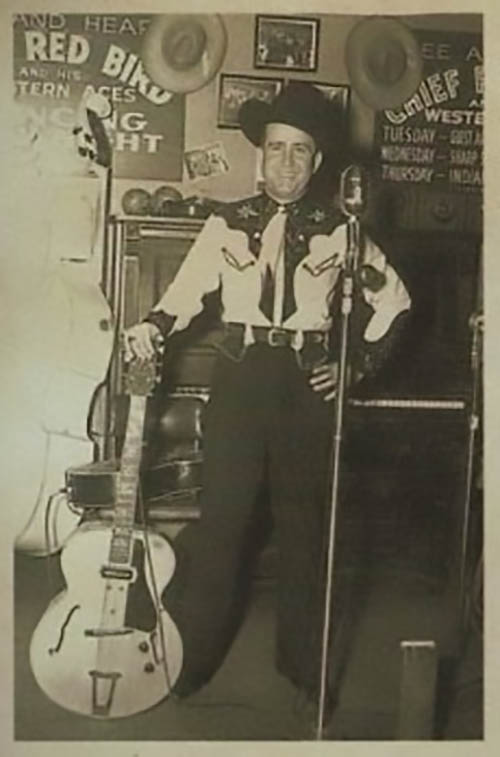

Skeets McDonald

But records never tell the whole story.

Today, with social media and everyone walking around with a camera and the Internet in our pockets, we can forget that whatever went on in any given local music scene 50 years ago, almost all of it went undocumented. What we have are the records, hopefully some studio session logbooks, maybe newspaper clippings here and there for the bigger players and whatever memories survive long enough to make it into an interview when the book gets written, if a book gets written. There are some big cracks in the house that builds and a lot falls through. If you get lucky, the musicians like to party hard enough and act like big enough assholes to each other that the stories are funny enough to remember. Let’s just say I got pretty lucky with this episode.

This Ain’t No Crazy Dream

We’ll start from 1954. For a few years now, Moon and Wynn Stewart have been playing together around Los Angeles. Buck Owens has started driving down from Bakersfield for session work at Capitol Records and, in about another year, he’ll be leading his own house band at the Blackboard in Bakersfield. Musicians in L.A. and Bakersfield are constantly driving back and forth to make whatever money they can playing music. And, actually, for the rest of this story, it’s gonna be impossible to keep track of where everyone is living at any given time because, add Las Vegas, Nevada, and everyone we’re going to talk about is living in one of these places and driving to the other two for paying gigs. For some of these guys, Vegas is probably the worst place in the world to be but several of them like Sin City so much they move there.

1956 is when I hear Ralph Mooney become Ralph Mooney on recordings. That may have happened earlier but it does not matter. By 1957, we’d be talking about Moon even if he’d never touched a pedal steel guitar in his life. Because he wrote “Crazy Arms,” the song that singlehandedly changed the sound of honky tonk music in 1956. Ray Price had the hit with it and it may be difficult now to hear how revolutionary it was then because everything that’s happened since was influenced by “Crazy Arms.” The story goes they were having a hard time getting a good bass sound in the studio. Ray Price suggested the bass play a 4/4 line instead of what would have then been a standard 2/4 bass line. Listen to the bass on Buck Owens’ first single, 1955’s “Down on the Corner of Love.” That’s a 2/4 bass line. That’s what a honky tonk bass player did until Ray Price’s “Crazy Arms” came out in 1956, sounding the way it did. Packing more notes into the bass part got rid of their sound issue. More importantly, it represents a major step toward Ray Price’s signature country shuffle sound. It’s his first #1 record and the song spends five months at #1, nearly half a year at #1. That’s more time at #1 than all but four other songs in the 1900s. And, when the public hears something new that they love that much, it’s not “new” anymore. It’s the way you do it from now on. 1958, Buck Owens’ first session at Capitol where he’s in control, gives him his first hit, “Second Fiddle.” Listen to that Ray Price shuffle, that bass and listen to Ralph Mooney. That’s because of “Crazy Arms.” That’s why Buck Owens thinks he’s “the great Ralph Mooney” the first time he’s got him in the studio.

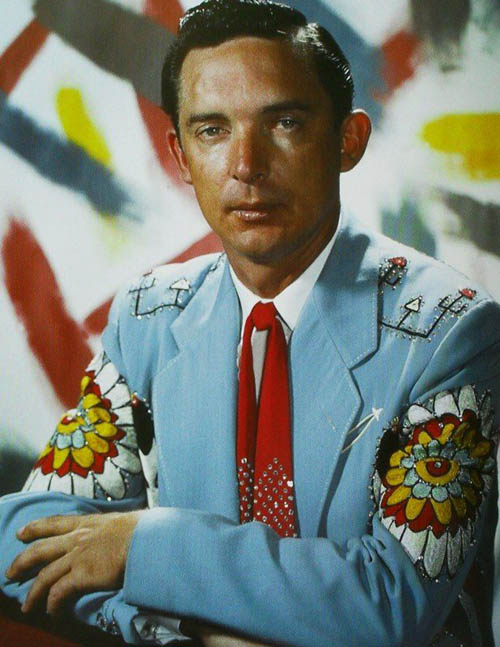

Ray Price

“Crazy Arms” was written by Mooney after his wife left him. Remember when I said Las Vegas was a bad place for some these guys to be? Ralph Mooney is one of those guys. Whatever else he’s doing out there, he’s for sure drinking a lot. According to Waylon Jennings in his autobiography, Ralph is getting “crawling, falling down drunk” let’s say… often. Mrs. Moon catches him with another woman and leaves, inspiring him to write the song with his friend, Chuck Seals. I don’t know exactly when all this happened but Waylon thinks it’s in Las Vegas in 1950. That sounds a little early to me but wherever and whenever the song was written, Hank Cochran tells my favorite version of how it got to Ray Price, so I’m going with him, “This guy in California had a wife who didn’t sing, but he thought she did, and she thought she did, and they would make records and put ’em out. Ralph Mooney was playin’ steel guitar, he was the hot thing out there, and he asked the guy, ‘Why in the hell don’t you start a publishin’ company and put the songs that you record in that company, and [see] what little airplay you get? If you get any at all, at least you’ll get some money from it.'”

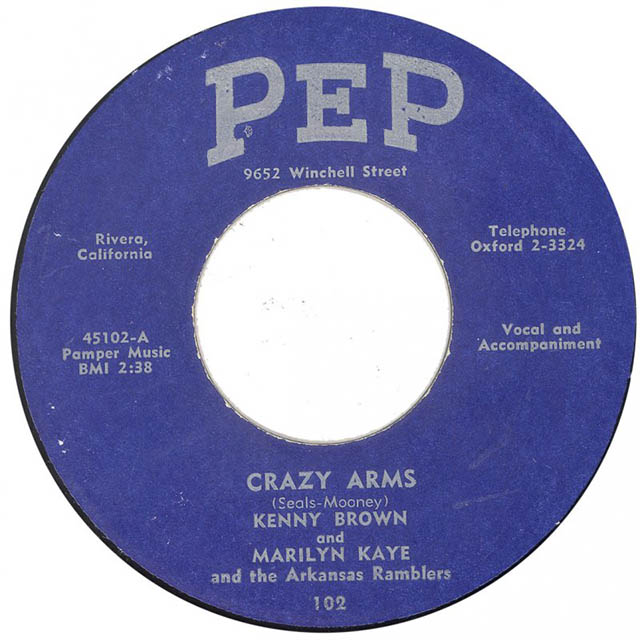

I’ll break in here to point out that Mooney was occasionally getting songs he wrote recorded in the sessions he’d do for Capitol. So, if you go back and look at a song he wrote, like “Ten Years Ago,” recorded by Bobby Austin, produced by Ken Nelson, you’ll see the publishing on that is with Central Songs. If you remember the Buck Owens episodes of this podcast, Hank Cochran’s story means Buck wasn’t the only one paying attention to where some of Ken Nelson’s supplemental income was coming from. Okay, so the guy with the wife who can’t sing gets up and goes to the bathroom and sees a bottle of Pamper Shampoo. He comes back and asks what everybody thinks of Pamper Music as the name of a publishing company. Everyone likes it and the guy asks if anybody has any songs. Back to Hank Cochran, “Ralph Mooney says, ‘Me and Chuck Seals has got a song called – it’s a little weird – called “Crazy Arms.”‘ [The guy] says ‘Well, is it good? You think we can do it? Well let’s try it.’ So they cut “Crazy Arms” on his wife, who couldn’t sing, and shipped it out. And this DJ in Florida played it a little, and he got all these calls – as bad as it was, because the song was so good. Ray Price comes through [the station] and [the DJ] says, ‘Hey, Ray, I’ve got a record that’s the worst you ever heard, by a woman who sings so bad, but the song gets calls you can’t believe every time I play it.'”

To make a long story short, Ray listens to the song, loves it, etc., etc. Hank Cochran’s story is funny enough but the real reason it’s my favorite version is that the guy with a wife who can’t sing is Claude Caviness and Hank calls him “Claude Cavendish” every time he mentions him. This is the same Claude Caviness who owns Pep Records and put out Buck Owens’ first singles, which would make Claude’s wife, Marilyn Kaye, whose recording of “Crazy Arms” that DJ would have played for Ray Price.

Ray takes the song, changes some of the lyrics and has such a big hit with it that Claude travels from California to Nashville to ask if Ray wants to make Pamper Music an actual publishing company, instead of just some words printed on a label. Ray brings in Hal Smith and they get to work, hiring Hank Cochran as their first staff writer, a young Willie Nelson as their second and Harlan Howard as their third. “Crazy,” “Hello Walls,” “Heartaches by the Number” and “Make the World Go Away” are only a few of the all-time legendary hits that come out of Pamper Music. It all started with “Crazy Arms.”

“Crazy Arms” goes on to be recorded by Chuck Berry, Mickey Gilley, Patty Loveless and far too many more artists to list them all here. When Jerry Lee Lewis records an audition for Cowboy Jack Clement at Sun Records in 1956, he plays “Crazy Arms.” In 1979, Ray Price records the song again with Willie Nelson and has a hit with it again. By the way, someone out there found an acetate demo of “Crazy Arms” sung by Wynn Stewart, dated 1954. Though it was never released, that would give him the first known recording of the song.

Two more important things that happen in 1956 are Wynn Stewart gets signed to Capitol Records and introduces Harlan Howard to Buck Owens. Those two go on to write some of Buck’s biggest hits together, including “Tiger by the Tail.” In 1961, Buck Owens will record an entire full-length of Harlan Howard’s material. It’s great. Ralph Mooney plays on it. When Buck hires his first touring pedal steel player, Jay McDonald, it’s specifically because he thinks Jay does an okay job of mimicking Ralph Mooney.

Bright Light City

This whole time, Moon is Wynn Stewart’s guy but he’s taking session work wherever he can get it and playing in other bands, too. Because the thing about Wynn Stewart is that he’s amazing at making records but, when it comes to everything else, Wynn is a total flake. He’s so bad at staying in communication with everyone on his team that he rarely even ends up touring after the release of a new single. He’ll disappear for months at a time, leaving everyone to get by on their own. 1959 finds Ralph Mooney in Gene Davis’ band at the Palomino Club. In 1960, he’s back with Wynn at George’s Round-Up and Roy Nichols is now in the band, too. These are Los Angeles venues. By 1961, Las Vegas is a hot town for country music. To this day, Vegas is a place where you can see once-in-a-lifetime performances from the best musicians in the world and I’m not talking about showrooms on the Strip. The headliners in those showrooms are some of the biggest names in music, meaning they have very, very good bands. Often, the incredible musicians in these bands will get done playing the same songs they play every night for work, head out to a low-key dive to meet up with other incredible players from other a-list bands and play until sunrise just for fun. The last thing they want to play is what they just got done with at their job. Left to their own devices, these musicians are going to cut way loose and dig into some heavy stuff they’d never get away with on the Strip. And they’re playing for the late night party crowds who want to dance, so, in the early 60s, that’s going to mean boogie blues of guys like Howlin’ Wolf and John Lee Hooker or the style of honky tonk music we’ve been calling the Bakersfield Sound, imported straight from California.

Years later, when an interviewer opens by telling Mooney that he’s the one who gave Buck Owens and Merle Haggard the West Coast Sound, the first two words out of Mooney’s mouth are “Wynn Stewart.”

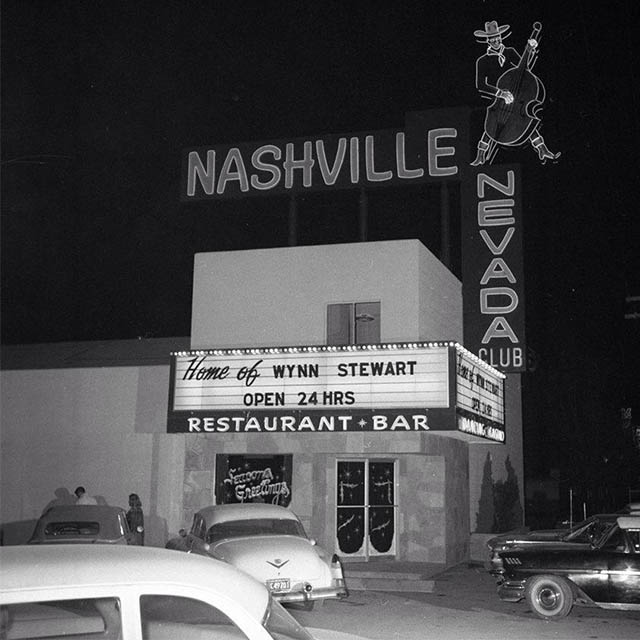

1961, Wynn Stewart is part owner of the Nashville Nevada Club in Las Vegas. His band is the house band. Again, it’s difficult to keep track of who’s living where because everyone’s always driving back and forth between Vegas and L.A. and Bakersfield. One of these trips between Los Angeles and Las Vegas, Mooney and Wynn are having some road beers and they pull over to take a piss next to an abandoned building. I don’t know why they have a can of spraypaint but they do and they paint COMING SOON – WYNN AND MOON on the side of that building. I wonder if they thought they were joking. 1961 is the year Ralph Mooney lays down one of the most recognizable pedal steel intros ever, on Wynn Stewart’s “Big, Big Love.” The song is rightfully recognized as a classic now and it does okay at the time but the real mark Wynn and Moon are about to make on country music together is just by playing the Nashville Nevada Club. The club stays open 24 hours a day. When you add in Wynn’s wonderful band, this is the late night spot. It’s in this room, not anywhere in California, where many hugely influential musicians and artists are first exposed to the Bakersfield Sound. The Bakersfield music scene is great and nationally touring acts do come through but the kind of national acts who tour in a car. Vegas is where all the people with #1 records are running around. Here’s what Moon said in one interview, “There was always a big crowd at the club. Everybody from the country bands would stop by after their set was over. Patsy Cline came by just before she died and told me she was going to record ‘Crazy Arms.'” What Patsy didn’t tell Moon is that she’d already recorded a demo of the song, years earlier. However, she did do “Crazy Arms” again, in her final recording session. The thing about this little Patsy Cline story is there was probably a star that big in the Nashville Nevada Club multiple times a week.

photo by Jay Florian Mitchell, via Nevada State Museum Las Vegas

Here’s what Merle Haggard said about the room, “The sound moved right through your danged body. It was the best sound system I’d ever heard.” It’s somewhere in 1962 that Merle starts showing up at the club. Roy Nichols is on stage playing one night when he sees Merle in the crowd, recognizes him from somewhere and, the way Merle tells it, “He just went to wavin’, almost throwing his guitar at me. He said, ‘Take this son of a bitch and play it for a minute and let me get to the bathroom.’ It was like a guy being thrown into the New York Yankees and they say ‘Hey, pitch one!’ Ralph Mooney said ‘Can you sing?’ I said, ‘Yes, I believe I can sing something.’” They do “Cigarette and Coffee Blues,” some other song and, then, Marty Robbins’ “Devil Woman,” which is not an easy song to sing the right way. I’m so pleased to tell you there’s a fantastic clip of Merle Haggard singing this song, doing his best Marty Robbins’ impersonation for a television audience… with Marty Robbins sitting at a piano, maybe 7 feet away from him. Merle sings it so well the audience can’t help but laugh. When it gets to the chorus, though, you can see Marty’s face and entire body language go from “haha, this is a good impersonation of me” to “hey wait a minute – this guy’s gonna put me out of a job.” The crowd loses it.

Merle tells the rest of the story of being on stage that night at the Nashville Nevada Club, “I was doing that song and in the middle of the dance floor I looked and there was Wynn Stewart, standing and looking at me with his arms crossed and his head kind of cocked over to one side.” Wynn offers Merle double of whatever he’s making, wherever else in Bakersfield, to come join Wynn’s band, be his bass player and backup singer. Everyone jokes that Merle isn’t a very good bass player. Or, I don’t know, maybe they aren’t joking but Merle is such a good singer that nobody really cares. He’s in Wynn’s band for about a year, until he gets a record deal with Capitol in 1963. His first single for Capitol is a brand-new Wynn Stewart composition that Merle asked if he could have, called “Sing a Sad Song.” Wynn’s entire band plays on the session, including Wynn on guitar. When it hits the Top 20, Merle leaves to go become a star.

Slick Slidin’

Wynn Stewart never should have lived in Las Vegas. He’s got a gambling problem, a drinking problem… At one point in the mid-’60s, he’s in such bad shape that his musicians vote him out of his own band. Mooney goes on tour with Merle Haggard for a bit but that doesn’t last very long. They’re up in Minneapolis when a real bad snowstorm hits. It’s so cold the bus won’t start and there’s so much snow they wouldn’t be able to drive anywhere even if it did. Mooney gets cabin fever at the hotel, decides he can get that damned bus started and drive it on home. Well, he does manage to get it started but the driver runs out and stops him from trying to go anywhere. That’s about the end of Ralph Mooney’s days as a Stranger. But you can hear his pedal steel on Merle Haggard’s first four albums, with two Top 5 Singles in there, “I Threw Away the Rose” and “Swinging Doors.”

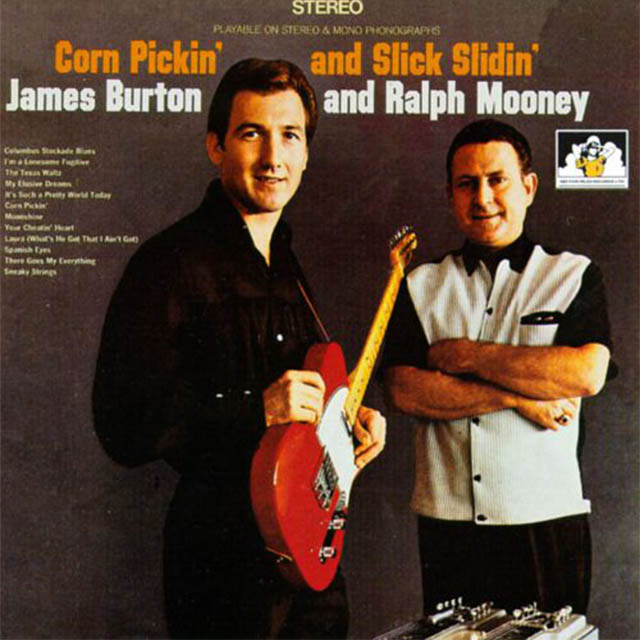

Moon spends the second half of the ’60s with more session work, making an album of instrumentals with James Burton right before James becomes Elvis’ Presley’s guitar player and, as always, off and on with Wynn Stewart. In 1965, Wynn resigns to Capitol Records and, in 1967, he has his only #1 single, “It’s Such a Pretty World Today.” Mooney is somehow not on that session but all his stories of being on the road with Wynn around 1969 give us a great idea of the kind of trouble these guys have always been getting in to.

Apparently, Wynn loves nothing more than to get real drunk and go fishing. They carry fishing poles and tackle everywhere along with all the band’s music equipment. He’ll make himself late to a concert if he sees a pond that looks like it might have some fish in it. Well, this one time, they’re in New Jersey with a week off. Moon and another guy in the band, named Hap Arnold, are staying in this cabin on a lake while Wynn flies home for a few days. When Wynn flies back, he’s bought a bunch of new fishing gear for that lake. He shows up with a fancy rod and tackle box plus bait and a huge bottle of gin. He wants to get fishing right away. First thing he does is haul all that gear out onto the old rundown dock, which collapses, and Wynn loses everything except for that bottle of gin. He doesn’t spill a drop of the gin. Moon and Hap still have their gear, so, after everyone gets done laughing at Wynn, they stay and fish until it’s so late they don’t even have time to cook the fish they caught before they have to leave. For some reason, they leave the fish in the cabin, maybe thinking the next guests will find them and eat them. Only, nobody else stays in that cabin for two weeks. By the time anyone does go in there, the smell is so horrific they’re told to never come back.

Another time, in Iowa, Wynn’s got a radio interview and Moon and Hap tag along since they’ve all three been out drinking the whole night. They’re listening to the station on the way there and Wynn keeps saying he thinks the signal sounds pretty weak for a 50,000 watt tower. They get to the studio. They’re standing around, waiting for the interview, when Wynn notices some big knobs that are not turned all the way up. Figuring that must be why the signal sounded weak in the car, he reaches over, cranks those knobs and blows the radio tubes, killing the station’s entire broadcast signal. Ralph and Hap sneak out the back door.

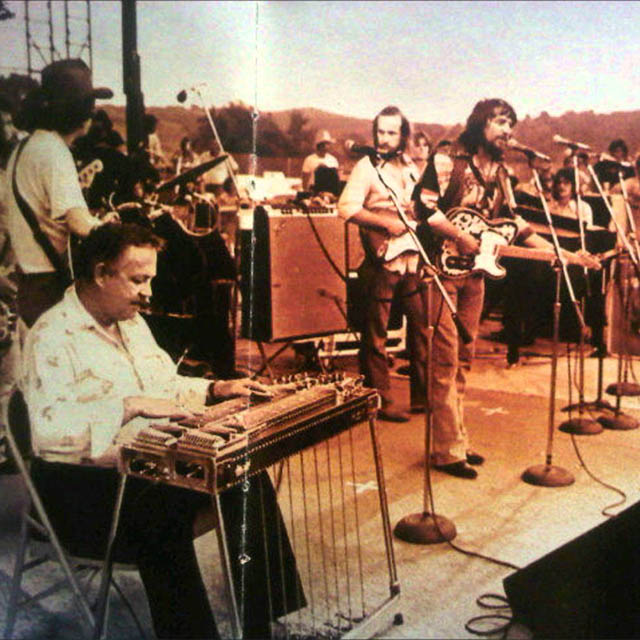

Thanks to Wynn’s #1 hit in 1967, their Vegas stops now have them in the big fancy showrooms, instead of the old honky tonks. One of the things that makes Ralph Mooney such a great pedal steel guitarist is that he truly loves his instrument. He never stops playing. There are so many people with a story about walking around somewhere, hearing Ralph Mooney practicing and hanging around to listen for hours, you get the impression he’d just as soon be homeless, as long as he had a pedal steel guitar. So, even on these showroom gigs, where you usually do at least two sets a night, a lot of times Moon and Roy Nichols will hang around onstage playing together between sets, just for themselves, just to play. The drummer, Richie Albright, is changing in to or out of his stage clothes one night in a dressing room at the Golden Nugget when he hears Moon working on some licks. Richie becomes so invested in what he’s hearing that he falls over on the floor while halfway inside a pair of pants. This is the story of how Ralph Mooney comes to meet Richie Albright’s boss and the man Moon will spend the next 20 years with, Waylon Jennings.

After writing a song that changed the way country shuffles are done, a song that led to Hank Cochran, Harlan Howard and Willie Nelson all writing songs for the same publishing company, after helping to create the Bakersfield Sound and export it to the high-profile music scene of Las Vegas, Ralph Mooney now moves on to a starring role in yet another major upgrade to the sound of country music: outlaw country.

On a Greyhound Bus

From 1971 to 1987, with no exceptions that I know of, every steel guitar part on every Waylon Jennings album is played by Ralph Mooney. Nearly all of the dobro parts, as well, sometimes both on the same song, as in “You Ask Me To.” According to many people who would know, Waylon Jennings is Ralph Mooney’s biggest fan. Richie Albright tells us that Waylon always said there’s only one steel guitar player and his name is Ralph Mooney. We can bank on those words because, in his autobiography, Waylon spends entire paragraphs talking about Moon and the general excellence of the other musicians in his band, The Waylors. In his words, “The band could do just about anything. It didn’t matter what the tune was. It just seemed like somebody would grab a hold of it and go. Get it started in one direction and then change direction, zigging and zagging. Mooney was at the heart of it. He was a cult legend in his own right, a steel-guitar genius, and he was in his heyday. When I played in England and introduced the band, Mooney got a bigger hand than me.” That goes for the records, too, of course. But what Waylon is really talking about here is playing with the band, show to show, out on tour.

There are bands that go out and play the same set of songs the same way in the same order, every single night. Then, there are bands that try to keep it interesting for themselves by throwing some curveballs to each other in the middle of the set, calling out songs they don’t often do, putting the emphasis on the rhythm in a different place, taking the lead breaks away from each other. You can hear a band like this in action by listening to how live performances of the same song will change over the years. Take “Lonesome On’ry & Mean.” You can find a version of that from 1975, in front of a small TV studio audience. Pretty laid back, Moon stays low-key in the first verses with a lick here and there. Compare that with the same song in the 1978 show, known as The Lost Outlaw Concert. They’re in front of a huge crowd and cooking right out of the gate. The tempo’s slightly faster and Moon’s playing busy lead over the entire first verse. That’s what Waylon’s talking about when he goes on to say, “He could be cantankerous but he had a touch on his instrument that went beyond steel decorations. If you weren’t in the pocket for him when he took his ride, you would be by the time he came out the other side. If it was early in the show and things hadn’t quite found their groove yet he had the unique ability to put it there, pumping pedals and stroking the bar across the strings.” This is the way someone would normally be talking about the drummer of a band. When musicians use terms like “in the pocket” or “finding the groove,” they’re always talking about the rhythm section, the drummer and bass player. I’ve never, ever heard someone talk about a pedal steel guitarist controlling the groove this way. Highly unusual. Waylon finds these concerts so fascinating they record every show and listen back to it each night on the bus.

Some of you noticed Waylon calling Ralph “cantankerous.” He goes on to say “if Ralph was shy when he was sober, he could be a holy terror” when he got near the bottle.” Bill Conrad, Waylon’s in-house publicist, has written a film treatment about his time on the job. Mooney is depicted as passing out on his instrument in the middle of a concert. Waylon speaks into the microphone, “The Moon has set.” I don’t know that Bill is even saying that really happened or not but Mooney puts in over 15 years of drinking on tour with Waylon. When country music fan and writer, Chet Flippo, goes on tour with Waylon, around 1972, he sees Ralph Mooney as someone who looks more like a bank teller than one of country’s great sidemen. Then Mooney tells Chet exactly how one goes about cleaning vomit from a pedal steel guitar, saying he’s only ever had to do it himself one time and, hopefully, won’t ever have to again. And Chet notices Moon sipping straight gin during intermissions.

In my opinion, the best Ralph Mooney story of all can be found in Waylon’s autobiography. He says Ralph was, “to say the least, a character,” then tells Chet Atkins’ favorite story about Ralph Mooney. Or, rather, about the fiddle player, Johnny Gimble, recognizing Moon on an airplane. Gimble’s a big Ralph Mooney fan, so he goes up to him saying “I’m Johnny Gimble, the fiddler, and I want you to know that I really love your steel playing. I appreciate your work.” Mooney, presumably drunk, replies, “Aw, fuck you.” So, Johnny goes back to his seat. It’s about a year after that when Gimble sees Ralph again in a recording session. This time, everything seems to be going really well between them, so Johnny asks if Moon remembers the time he told Johnny “fuck you” on the airplane and what exactly did he mean by saying “fuck you” on the airplane? Mooney says, “I meant fuck you.”

Know That It’s Real

Ralph Mooney didn’t spend the rest of his life just riding busses and planes around the world from stage to recording studio to hotel room, drinking gin and telling innocent fans “fuck you.” If you asked him, he’d tell you that he would have starved to death except for those royalty checks from “Crazy Arms.” I’m sure that’s a joke but I’m also sure those checks were nice, so it’s not surprising that he kept writing songs. In 1983, Johnny Rodriguez had a Top 5 Hit with a Ralph Mooney song, called “Foolin’,” produced by Richie Albright. Ralph showed up on some projects for other artists in the ’80s. Neil Young’s Old Ways album from 1985 is not the favorite album of many fans but Moon did great work on it. One of Buck Owens’ final studio albums was 1988’s Hot Dog. He re-recorded “Under Your Spell Again,” which Mooney had played on, so they brought him back to play on it again. In the session, he kept kicking off “Foolin’ Around,” instead of the song he was supposed to do. When Buck came over the studio monitor to tell him he was playing the wrong song, Ralph said, yeah, but he liked that one better.

In 1988, Mooney had a heart attack, quit drinking and quit smoking. Wynn Stewart had died of a heart attack in 1985, at the age of 51. I don’t know if these things informed Mooney’s eventual decision to get off the road but he did retire in the 90s, spending most of the last 15 years of his life quietly at home.

Well, maybe not quietly.

Marty Stuart & Ralph Mooney

Thank you for listening to (and reading) Cocaine & Rhinestones. Not only this episode but the entire first season, which is now at an end. There is no scheduled release date for the second season, as I’ve never done this before, have no way of predicting how long it will take and it’s all going to depend on some things I need to talk about in a minute. There will be a Q&A episode of the podcast released on Feb. 6th. You need to email whatever it is you want to know to questions@cocaineandrhinestones.com by Jan. 30th to have a chance of it being answered on the podcast. Get those questions in soon. BONUS: Cocaine & Rhinestones Season 1 Q&A Episode!

Every episode of the podcast is written and produced by me, Tyler Mahan Coe. Honestly, it takes a lot more than writing and production for this show to happen. Those are just the two things I’m most proud of, so that’s why I say that every time. There are no research assistants. There is no recording engineer, no script doctor, no editor of any kind. It’s all me, which is the way I believe it has to be in order to come out the other side of that process with this podcast. I’ll spare you a list of the details but creating an average episode takes around 100 hours of work. The first season has 14 episodes and it took me seven months to make. If you do all the math, that’s two 40-hour work weeks plus ten hours every weekend, per episode. As you can imagine, it’s not possible for me to have any sort of job while creating Cocaine & Rhinestones. In order for me to be able to keep doing this, Cocaine & Rhinestones has to become my job.

Again, I’ll spare you the details but I went way out of pocket to create the first season of this show. Nobody asked me to do that. I’m not complaining about anything, I’m not saying anyone owes me anything and I certainly don’t regret doing it, as I’ve seen enough of a response to believe it was a smart investment in the future. All I knew when I started was that this is important and that I had to try. I knew I had to let you know what I was capable of doing before you could decide whether or not it has value to you and how much that value may be. You know, the first taste is free. So, I made the decision to do that and that’s what I’ve done. You’ve heard what I can do and what I want to spend the rest of my life getting better at doing. I’m not about to tell you that it will cost money to listen to this show from now on. I don’t ever want to do that because I want as many people as are interested to be able to hear this history of country music. The entire point of doing this is to make as much noise as possible and charging a fee at the gate excludes a ton of people. What I’m about to tell you is that I’ve done what many of you have already asked me to do: I’ve set up a Patreon page for Cocaine & Rhinestones.

I know that many of you have never heard of Patreon. It’s pretty new to me as well, so here’s what it is: it’s a website where you can support this podcast by making a financial contribution every month. This is a way that you can help me continue to make this podcast. My Patreon URL is patreon.com/tylermahancoe and you can go there to read more about how it works, sign up to become a patron and choose how much you want to contribute. We’re talking as little as $2 a month, here. To put that in perspective, the average price of a movie ticket in 2017 was $8.97. Let’s round that down and call it $8. If you choose to send in $2 a month to me for one year, that comes out to $24. So, for the price of three movie tickets, you can do the bare minimum it takes to support one year’s worth of Cocaine & Rhinestones. Of course, if you want to, you can send in more than that. There are multiple tiers at which you can support the podcast and I have a lot of great ideas for how to reward podcast supporters at different levels in the future. For right now, you’re pretty much just doing it because you want to support the podcast. If you feel like I’ve already given you something with the first season and you want to give me something, this is how. If you love the podcast and want me to keep being able to make it and make it even better than it is now, this is how. There are a few minor rewards currently available at different levels. Anyone who contributes anything at all will get access to a patron-only news feed where you’ll see a monthly update post from me. Higher level contributors will be able to vote in a poll to help decide the topic of one episode per season, which is the closest you’re ever going to get to me taking requests. You can go to my page on Patreon to read more about all of that.

There are a couple more things I need to say about Patreon, just to be clear. This is not a tax-deductible charity donation and this is not a way to pay for receiving a product. This is a way to contribute to the process that results in a product that you enjoy or that you think is important. There will be several months a year when new episodes of the podcast are not being released. Those are the months when I’m working hardest on the show. Those are the months when your ongoing support is helping me create Cocaine & Rhinestones. In other words, as you hear me say this, I’m preparing to begin work on the second season of the podcast. All of the money spent on creating the second season will be spent before you hear one minute of the second season. So if you want to help me do that, if you want to become a patron of the show, there is no better time than today.

The final thing I need to say about Patreon is this is only for people who want to know they’re helping me create this podcast and who are in a position to be able to do that. If money is a problem for you right now, do not do this. I need you to understand that I do not want your money if it’s difficult for you to give it to me. Do not neglect your personal well-being to contribute to a podcast, any podcast, I don’t care how much it means to you. I’m not a televangelist. I do not want your last dollar.

If you can’t become a patron right now, you can still help by continuing to tell others about the show. The reason I ask you to share every episode with one person is because that is effective. The audience has grown so much faster than I expected and I know for a fact that’s because of those of you who’ve been talking about it. I appreciate it so much and I need you to keep doing it between seasons. If you want to do more, step it up a notch. Hit those Facebook groups, those subreddits, those message boards – anywhere you aren’t breaking a rule by posting a link – it really does help. Anything you can do to get more people to listen, that matters so much.

One more thing, every episode is made with repeat listening in mind and the entire season was structured with repeat listening in mind. I believe if you start at the beginning of the season and listen back through, you will find it even more satisfying than the first time. I’m not going to tell you where I hid all the easter eggs but there’s a lot of stuff I don’t think you would have noticed the first time through, especially in the song clips.

-TMC

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [linked, if available]:

- Bud Hobbs & His Trail Herders – “Louisiana Swing” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Merle Haggard – “Singin’ My Heart Out” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynn Stewart – “I’ve Waited a Lifetime” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Maddox Brothers & Rose – “George’s Playhouse Boogie” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jimmy Bryant & Speedy West – “Arkansas Traveller” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Sheb Wooley – “Country Kisses” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bob Wills & The Texas Playboys – “Steel Guitar Rag” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Skeets McDonald – “I Got a New Field to Plow” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Eddie Kirk – “Candy Kisses” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Webb Pierce – “Slowly” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tennessee Ernie Ford – “I Ain’t a-Gonna Let It Happen No More” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Skeets McDonald – “Strollin'” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Glen Glenn – “A Hundred Years from Now” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Skeets McDonald – “Keep Her Off Your Mind” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wanda Jackson – “Honey Bop” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynn Stewart – “Wishful Thinking” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ralph Mooney – “Release Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Buck Owens – “Down on the Corner of Love” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ray Price – “Crazy Arms” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Buck Owens – “Second Fiddle” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobby Austin – “Ten Years Ago” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Kenny Brown & Marilyn Kaye – “Crazy Arms” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Chuck Berry – “Crazy Arms” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Mickey Gilley – “Crazy Arms” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Patty Loveless – “Crazy Arms” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynn Stewart – “The Waltz of the Angels” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Buck Owens & His Buckaroos – “Foolin’ Around” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynn Stewart – “Big, Big Love” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Patsy Cline – “Crazy Arms” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Merle Haggard – “Sing a Sad Song” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Merle Haggard & The Strangers – “Swinging Doors” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- James Burton & Ralph Mooney – “Corn Pickin'” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynn Stewart – “It’s Such a Pretty World” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Waylon Jennings – “You Ask Me To” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Waylon Jennings – “Memories of You and I” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Waylon Jennings – “Lonesome, On’ry & Mean” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Rodriguez – “Foolin'” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Marty Stuart (ft. Ralph Mooney) – “Crazy Arms” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Commentary and Remaining Sources

It’s almost always ridiculous when people say one song is the first song to represent this sound or that sound. That’s just not the way that music evolves. Take a song like Bud Hobbs’ recording of “Louisiana Swing.” I would never tell someone that is the first song with the Bakersfield Sound on it. That’s just a thing I’ve seen other people say and in this episode you heard some of my thoughts on that. I’ll go one step further and say I don’t think it’s possible to label any one recording as the first recording of the Bakersfield Sound. Because that sound didn’t come from recording studios. It evolved in honky tonks over a period of time of who knows how long? You could try to make a list of every person you believe is responsible for creating the Bakersfield Sound, then go track down every recording all those people ever made, until you get to the earliest one. Do you really think that’s going to sound anything like what we think of as the Bakersfield Sound? I strongly doubt it. That recording session probably didn’t even happen in California. The Bakersfield Sound happened on stages and then found its way into recording studios. And, yeah, as I mentioned, a certain style of production came to be thought of as the Bakersfield Sound but that was after it was created. That was later. So, I generally regard that sort of “search and label” mission like this as a colossal waste of time.

Now that I’ve said all of that, some of you are thinking, “Okay, well, wait a minute. Didn’t you spend 15 minutes of this episode telling us how the song ‘Crazy Arms’ was the first song to sound like that and how it’s the one song that made all of these other things happen?” Yes. These are very different circumstances. The sound of “Crazy Arms” did not evolve over a long period of time in a local music scene, in recording studios, anywhere. It wasn’t “this band started doing this,” so “that band started doing that” and, eventually, all the bands were doing this new thing. “Crazy Arms” was a big bang. The evolution of that sound happened in the span of maybe an hour, in a recording studio, to fix a very specific problem they were having. We’re literally hearing the recording of the first time that ever happened. And, yeah, it is possible there was some country band, somewhere in the world, who’d hit on the idea of having the bass player use a walking 4/4 line over an entire shuffle instead of going into or out of a measure. But we have no evidence of that being the case and, as far as I know, nobody has ever even made a claim of that being the case. What we do have is the rare song that truly did change the game as much as people think it did, which is “Crazy Arms.” There is no gray area, here. There is before “Crazy Arms” and there is after “Crazy Arms.”

I’m aware that Ray Price gave a lot of interviews saying he brought that 4/4 bass line into the studio, like it was a creative decision that he’d been thinking about for a while. I don’t believe that’s how it happened. In those early interviews, he gives statements like he doesn’t really know what gave him the idea, he was just trying to find his own sound. Yeah, yeah, this is what people do. They accidentally hit on something and then convince themselves it was on purpose. In later years, he started telling the real story, which is that Buddy Killen, the bass player on that recording session, wasn’t getting a good, clean sound. So, Ray suggested a solution and it changed country music forever.

I mentioned that Wynn Stewart re-signed to Capitol Records in 1965. His first deal with Capitol only lasted for about a year because of the things I mentioned in the episode, namely, his singles only performing so-so, largely due to his lack of interest (or ability) in performing the role of a major label recording artist. But I failed to explicitly state that this led to the end of the first contract before mentioning the second one, so there you go.

I should point out that Buck Owens was very clear about being influenced by Wynn Stewart. It’s not like Merle Haggard was the only one going around saying that. I needed to use that Merle Haggard quote there because I needed to address the fact that Merle Haggard had no hand in creating the Bakersfield Sound. Otherwise, everyone who mistakenly believes that would wonder why his influences weren’t discussed more in the episode. And I sincerely do not care if anyone is mad at me for saying Merle Haggard was almost a Marty Robbins impersonator at the start of his career. He was. Listen to the records. Hell, his Marty Robbins impersonation is literally what led to him being in Wynn’s band, which is what led to him recording Wynn’s song with Wynn’s band and that was his first hit. So, yeah, I’m not sorry.

I’m positive that I already have emails from pedal steel guitar players who couldn’t even finish the episode before letting me know how stupid I am. Full disclosure: I am not a pedal steel guitarist but I am fascinated with the instrument and do believe I can say a bit more about the evolution of the sound and functionality of it without sounding like a total dumbass. I said most people will tell you that pedal steel became the big thing in country music when Bud Isaacs played one on Webb Pierce’s, “Slowly.” Then I told you that everyone had actually been hearing pedal steel from Speedy West in California since 1949. These are objective facts. But when 99.9% of people who do not play any version of steel guitar listen to Speedy West’s early pedal steel guitar playing, it probably sounds to them exactly the same as non-pedal steel. There are two very simple reasons for that. The first reason is that people playing these early pedal steels had never played one before. So their initial approach was one they’d already been using on non-pedal steel with one minor change. That minor change is responsible for the second reason it sounds the same to most of us. What we think of as the sound of a pedal steel guitar comes from the pedals and levers being manipulated to bend individual strings while they’re already sounding notes from the instrument. It’s generally accepted that Bud Issacs was the first person to do this on record in the 1953 session for “Slowly” by Webb Pierce, which became a hit the following year. Everyone who thinks that is wrong. Bud Isaacs himself says he did the same thing on earlier recording sessions. It’s just those recording sessions didn’t lead to #1 hit songs, like “Slowly” by Webb Pierce.

To try and explain this in a different way, he played several strings in a chord and then pressed the pedal so two of the notes we were already hearing would bend and we could hear the sound of that bending. What Speedy West and other pedal steel players were doing prior to this was pressing down on a pedal to bend strings before they were played. We, the listener, would then be hearing pre-bent notes without hearing the sound of the bending. Again, for 99.9% of people who do not play steel guitar, this sounds exactly the same as non-pedal steel. But any steel player at the time who wasn’t aware of the pedal innovation and heard them doing this, especially in a chord, it would drive them crazy trying to figure out how they were getting those notes in there. And, if none of what I’m saying right now makes any sense to you at all, that’s why I saved it for the Liner Notes because only pedal steel guitar players are going to care.

I didn’t talk about it in the episode because it honestly didn’t even occur to me that there are people who wouldn’t know about it but the pedal steel intro on Waylon Jennings’ “Rainy Day Woman” is, of course, identical to the one on Wynn Stewart’s “Big, Big Love.” If you knew about that and you were expecting to hear about it, hey, you already knew about it. And if you didn’t know about it, I just told you. Go check it out.

There were some awesome sources used for this episode.

First, there’s Roadkill on the Three-Chord Highway by Colin Escott. The reason I’m talking about that first is that it’s one of my favorite books written about music, period. It’s a collection of biographies on American musicians who are mostly not talked about as often as they should be. Roy Orbison and Jim Reeves are in there but you’ve also got an entire section dedicated to Skeets McDonald and another one dedicated to Wynn Stewart, two of the most underrated artists in country music. I can not recommend this book enough to anyone who enjoyed this episode or, really, any other episode of this podcast. Colin’s approach to music writing is what I aspire to with Cocaine & Rhinestones.

I referenced Waylon Jennings’ autobiography several times. Man, what a book. Listen, if you don’t like to read, you should get the audiobook version because it’s got Waylon reading it himself. It’s so badass. You need that in your life.

The very problematic Buck Owens biography and Buck Owens’ autobiography from the Buck Owens and Don Rich episodes were used as sources for this episode. I don’t feel like repeating myself by talking about them here. If you missed those episodes, you really need to go back and listen to them and listen to those liner notes for everything you need to know about those two books.

Another book I’ve told you about before, How Nashville Became Music City USA by Michael Kosser. This is another book that I think every country music fan should own. I believe I told you about it in the Liner Notes of the Shelby Singleton episode. The title tells you everything you need to know. It’s a great history of Nashville and the people who came to play major parts in Nashville. Hank Cochran’s “Claude Cavendish” story came from this book. It just goes to show that you can personally know someone, they can play a huge part in your career and you can still spend the rest of your life saying their name wrong.

[I forgot to mention it in the recording but Gerald W. Haslam’s Workin’ Man’s Blues: Country Music in California was also used as a source for the episode.]

Lastly, the Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World: Volume 8 on North America is a great resource with a solid entry on the Bakersfield Sound. It’s a nice, little summary overview. However, there is some pedantic speculation on whether or not the Bakersfield Sound even exists because Buck Owens went on to record songs like “Bridge Over Troubled Water” or used a string section, here and there. This is absolutely inane logic. Of course the Bakersfield Sound exists. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Alright, that’s it. I’ll be back in two weeks to answer a whole bunch of your questions. Again, you need to email questions@cocaineandrhinestones.com by January 30th to have any chance of your question being answered in that episode. It’s possible that future Q&A episodes may be an exclusive reward for patrons of the podcast, I don’t know. Make sure to get a question in, if there’s something you want to know. I’ll go ahead and tell you, though, you’re wasting your time if your only question is am I going to do an episode on this artist or that artist. Unless you’ve heard me say otherwise, the answer is “yes,” I’m planning to do an episode on that artist. BONUS: Cocaine & Rhinestones Season 1 Q&A Episode!

If you skip the Q&A episode because you don’t care, you’ll hear from me again at the beginning of season 2. I have no idea how long it will take. Please believe I’ll be working my ass off the entire time between now and then. I want to get it done as soon as possible but I’m also not going to rush anything because some things in this first season were rushed and I know the show could have been better if they weren’t. If you still don’t subscribe to the podcast anywhere, you definitely should – on whatever app you use to listen or subscribe by email so you’ll at least get an email when new episodes come out. When I do have a release date for the second season then I’ll probably make a small trailer episode to announce it and everyone who subscribes will get that.

One more time, I can’t end without saying thank you, again, for listening to this podcast. Thank you so much for listening, for sharing, everything else. I hope I can keep doing this. Thank you.

Ralph Mooney’s obituary in the L.A. Times

Chet Flippo’s eulogy of Ralph Mooney for CMT.com

2003 interview with Ralph Mooney by the Nashville Tennessee Steel Guitar Association

Near to the Maddening Crowd – Texas Monthly oon

History of the West Coast Playboys (Wynn Stewart’s Band) from the Rockabilly Hall of Fame

History of Jim Pierce from the Rockabilly Hall of Fame

Ralph Mooney’s Road Stories with Wynn Stewart from countryclassics.com

“Waymore’s Ghost” (A Working Title/Extended Film Treatment) – No Depression