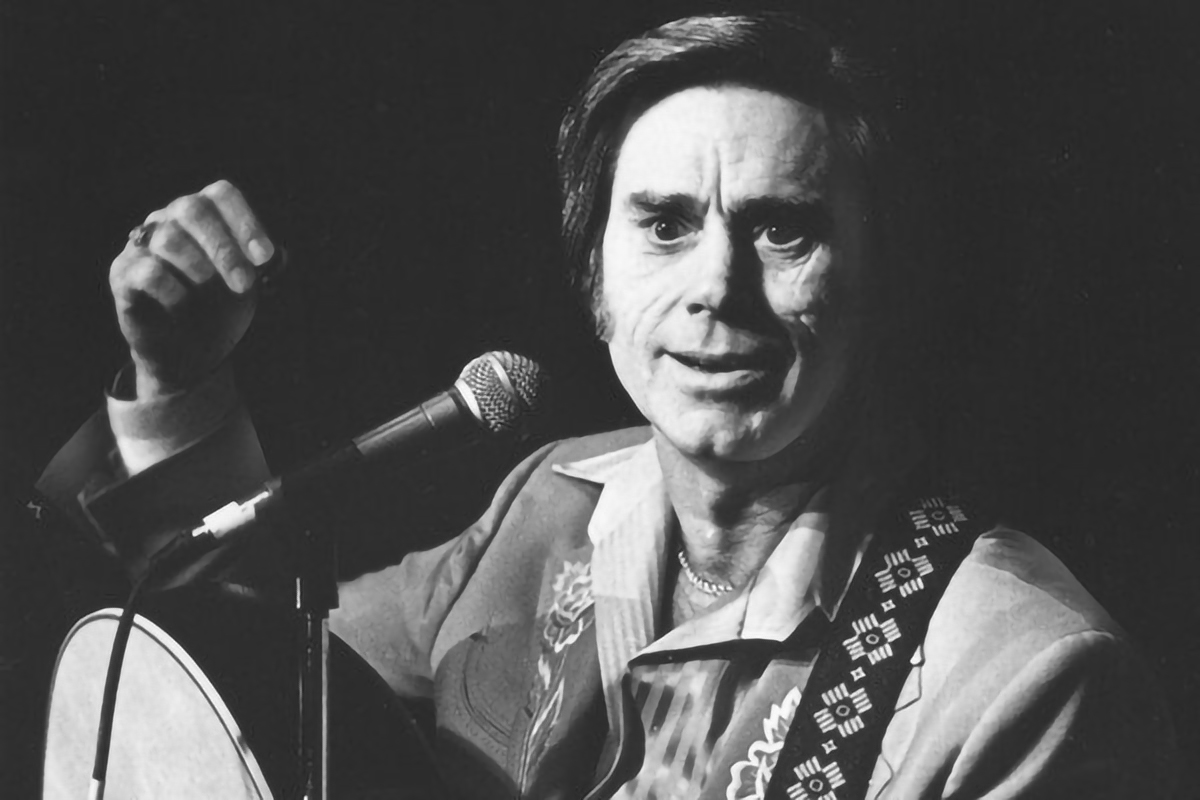

Oh, you’re back to hear more things that will chill you to the bone? Then we can talk about what George Jones’ life was like in the period leading up to and through the biggest hit of his career. If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to be afraid of a demonic duck or try murdering your best friend to test the existence of God, well, these are questions only George Jones can answer but just asking them makes for one jaw-dropping and heartbreaking story.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

My main sources for this episode are all on The Main Library and Season 2 Library pages of this website.

Transcript of Episode

As part of my agreement with Simon & Schuster to publish a book adaptation of Season 2, the transcripts that have been freely available for over a year will be temporarily removed from this website. Please consider ordering a copy of Cocaine & Rhinestones: A History of George Jones and Tammy Wynette through your favorite local bookstore or requesting that your local library order a copy you can check out.

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [with links to purchase or stream where available]:

- Stuff Smith – “You’se a Viper” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Fats Waller – “The Reefer Song” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Victoria Spivey with Lonnie Johnson – “Dope Head Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ethel Merman – “I Get a Kick out of You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Lead Belly – “Take a Whiff on Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Luke Jordan – “Cocaine Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dick Justice – “Cocaine” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Charlie Poole & The North Carolina Ramblers – “Take a Drink on Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones & Johnny PayCheck – “Maybelline” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Someday My Day Will Come” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones & Elvis Costello – “Stranger in the House” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones & Johnny PayCheck – “Proud Mary” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones & Johnny PayCheck – “When You’re Ugly Like Us” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones & Tammy Wynette – “Two Story House” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “If Drinkin’ Don’t Kill Me (Her Memory Will)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones & Georgette – “Daddy Come Home” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Barbara Mandrell – “I Was Country When Country Wasn’t Cool” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Excerpted Video

These videos were excerpted in the episode. For any number of reasons, YouTube (or DailyMotion) may remove them in the future but here they are for now:

Commentary and Remaining Sources

These Liner Notes will be brief.

Because the first George Jones biographies started coming out a few years after Jones’ biggest success and biggest troubles circa “He Stopped Loving Her Today” and because of how much he portrayed Shug Baggott as a villain at the time, which is what he continued doing the rest of his life, Shug became a huge character in the George Jones story, though I’m not sure how much that’s warranted. He’s in this episode of the season and only this one because that seems to me to be the extent of his relevance to the George Jones story. I certainly think it’s more significant that Jones didn’t have modern concepts of alcoholism and addiction explained to him until he was a 50 year old man and that the first time he ever did cocaine it was because some doctor gave it to him every night for a week. Mostly, I think Shug Baggott was just the guy who happened to be there and if it wasn’t him then it would have been someone else. I’ve heard a lot of stories about this man my whole life and I’m not going to repeat anything that isn’t confirmed by credible sources but when I said he became the cocaine dealer to the stars in Nashville, that’s true. Not that this makes him a great humanitarian or anything but, for what it’s worth, the reason he was sentenced to three years in prison is that he wouldn’t roll over on anyone or name names and he never did. When he got out of prison, he became a preacher. At one point, there was an attempt to crowdsource funds for a documentary about him and, though it wasn’t successful, I wish it had been because, well, let’s just say it’s pretty likely Shug Baggott’s name will come up on the podcast again in future seasons.

One thing I thought was interesting given the current state of the abomination that is Lower Broadway in Nashville, when George Jones opened his second Possum Holler location (in Printer’s Alley), he was already talking to the press about how the other nightclubs downtown were starting to cater to a rock audience and how he wanted to keep his place country, which is what he did.

A couple notes on the voices of his split personalities. One, duck voices were a really popular comedy act back in the day, so it’s ultimately impossible to say where Jones picked up his. The clip I used was not actually DeeDoodle but it was George Jones in a recording session for “I Made Her That Way” which took place all the way back in 1965, almost 15 years prior to DeeDoodle’s existence. Looking at that time frame, I’m going to point out the possibility that Jones saw the duck voice routine of a guy named Ray Atkins, who played dobro for Johnnie & Jack. As for the Old Man, if you track down a George Jones songbook titled Song and Picture Folio published by Glad Music in early 1964, you will find a picture of George Jones standing with Walter Brennan.

My main sources for Season 2 are all on the Season 2 Library page.

There are two more George Jones sources I need to give individual commentary in this season’s Liner Notes, so I may as well take care of that here.

First, the autobiography, which I already said in an earlier episode is more like Jones reacting to other people’s memories because by that point he didn’t have many of his own left. It’s an engaging read but has a tendency to inspire more questions than it really answers. If you’re mostly interested in Jones’ recording career, go ahead and skip this book. At one point he straight up says he can’t talk very much about his sessions because he doesn’t remember most of them.

At the other end of the spectrum is The Grand Tour by Rich Kienzle. Rich is the guy who did the booklets for all but one of the George Jones Bear Family box sets also used as sources this season, so he know more about Jones’ recording career than Jones knew about it himself and that’s mostly what Rich chooses to focus on. As a standalone book, this wouldn’t be “the one Jones biography” I’d recommend (but none of them would be or I’d not have spent Season 2 talking about him). Rather, this is a good book for everyone who’s read one or two of the other ones, wants the author to gloss over the salacious bits everyone else spends most of their time on and get to the records, even tracking down sources who were in the studio yet not quoted very much by other authors.

Alright, when the podcast returns, just like Agnes Nixon taught us to do, we’re going back for one last episode on Tammy Wynette.