Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

There were no books used for this episode other than those found in The Main Library and the Season 2 Library. Other main sources below.

Transcript of Episode

A Little War

In the 5th Century A.D., after the fall of the Roman Empire, pretty much all of Europe was up for grabs. Entire nations of people immigrated to the continent while others fled. This was the time of Viking marauders. Anything was yours if you could take it by force, whether your own or that of an alliance made through any combination of wealth, religion, family or fear. Various territories formed themselves into kingdoms, states and republics with names you’ve never heard because they were soon conquered or allied through some treaty and renamed, again and again and again. As political order began to define itself within this chaos, the most successful nations were those with prosperous lands and enough wealth to hire and reward the militaries needed to defend and/or acquire the prosperous lands and wealth. Following great victories, warriors who’d excelled in battle stood (or kneeled) to receive knighthood, money, advantageous marriage, property and serfs, all meted out according to (and possibly including a promotion of) rank and title. In the peacetime which followed war, however brief and intermittent, knights found themselves with too much free time and not enough people to kill. Whether you’re a king or some lesser lord, you don’t want your warrior aristocracy sitting around with no reason to keep themselves or their battle skills in shape. Even worse, you don’t want them conspiring with each other to find a reason to use those battle skills, possibly against you in a coup d’état. By the end of the 10th century A.D., entering the High Middle Ages, a solution had been found: miniature, pretend wars, called “tournaments.” Do not be fooled by the word “miniature.” These pretend wars may not have spanned the lands of entire nations but, like a real war, tournaments were scalable. As the game quickly caught on over the next hundred years, the designated in-bounds area of any given tournament could be an enormous size, as large as all the connecting forests and pastures of the wealthiest participating or sponsoring lords. We’re talking miles of land. Sometimes it was more like acres, sometimes as small as a field or fenced-in enclosure without even enough room to use horses.

No matter the scale, this was different from any earlier combat sport or training exercise. This was medieval warfare with everything but the political grievances and killing… or, at least, without as much. Smaller tournaments were often every man for himself but teams were usually chosen for the larger affairs. And when teams were chosen, it was sometimes arbitrarily but other times according to very real and serious sociopolitical divides, with participating knights grouped onto opposing sides of personal feuds or governmental conflict. For example, teams could be split by which of two countries knights were born in or which country they intended to support in a war everyone knew could start any minute, perhaps even right here and right now if someone gets too worked up to remember the part about not killing each other during this game. The idea was to keep tournaments non-lethal but the idea was also to beat the shit out of each other with blunted swords and larger tournaments typically began with both sides launching a full cavalry charge at each other, so accidents happened. “Accidents” could also very easily be made to happen in such an environment, should personal vendetta or political gain provide sufficient motive. Evidence points to the term “freelance” originating as a noun to describe a knight who was available should any noble house have need of representation in some prestigious tourney. Should said noble house have need for a certain knight to die in the tourney, well, it was probably a good idea to send in a freelance rather than a knight of the house.

Even without contract killing, the very nature of medieval warfare made this an extremely lucrative game for mercenaries. Because in non-tournament war, they did use real weapons to kill people on the other side… but not all people on the other side. Because, in the Middle Ages, all men were not born equal. Infantrymen and commoners died by the thousands in war but if a knight surrendered in battle or you were otherwise able to capture him as a prisoner, the smart thing to do was keep him alive. The closer he sat to a throne by blood or marriage, the more valuable he was as a bargaining chip. If his family happened to be rich (and there’s a solid chance they were), a great ransom could also be demanded for this prisoner’s release. The awesome thing about tournaments is everyone on the other side was a knight. In fact, it was a rule that everyone had to be a knight. In fact, you could say this was the only rule of a tournament, implying all others with this one simple twist on a familiar concept: it’s war, except everyone’s a knight. Since knights were meant to be captured and not killed in war, everyone may as well use blunted swords, etc., etc. In war, real or pretend, when a knight surrendered, his captor was owed a ransom of money, weapons, armor, a horse, whatever was deemed valuable enough to grant any given knight’s release. The particulars of these and other tournament matters were dictated by ever-evolving customs of warfare and “chivalry.”

Like feudalism itself, chivalry is a concept that has been defined and redefined to a point of mass confusion and near meaninglessness. It began not much at all to ensure men held doors open for women. The original scope of chivalric concerns had much more to do with warfare, as knights were primarily weapons of war. The word “chivalry” comes from chevalier, the French word for “knight,” which shares a Latin root with both “cavalry” and caballero, the Spanish word for “gentleman.” All of these words implied at least ownership of a horse, if not full knighthood. “Cavalier” comes from the same place and also meant “knight” before it became an adjective for men who walk around with their heads up their own asses, which (as you’re about to hear) is not a coincidence. Modern misconceptions of chivalry are probably the lasting result of how much fiction in and about this period leans on romantic plot to both rationalize and soften the violent behavior of knights, their typical male protagonists. How to treat a lady of the court (as opposed to a commoner) was covered by chivalry, sure, but nowhere near as much of a priority as how a knight should conduct himself in pursuit of his military obligations toward God, church, country, honor itself and various other personal pledges he may have sworn. It’s often pointed out how remaining faithful to all these loyalties at once would pose quite a challenge, especially in an era prior to concepts like separation of church and state, a time in which popes selected from noble families assigned important government positions to relatives and formed political alliances with kings, who were believed to rule by divine right. Such great potential for internal conflict is what makes the knight an attractive character to storytellers. The very nature of his existence demands sacrificing one loyalty in aggressively violent defense of another, thus revealing his most deeply held convictions. Within a hundred years or so of pretend war between knights becoming a popular form of entertainment to the ruling class, poems, novels and “history” books written in the 12th century changed chivalry forever through epic fantasies about legendary characters doing magical things during a golden age of chivalry (and wizards) that supposedly existed hundreds and hundreds of years before – Saint George killing a dragon, King Arthur and his knights relentlessly questing to become evermore pure while searching for the Holy Grail. Because these stories demanded glorious acts of violence from knights, such behavior was provoked and motivated through artificially inflated romance and fantasy. These extremely popular texts became the instruction manuals of chivalry, documents of contemporary ideals projected on to heroes in a distant and magical past.

It never mattered whether any of it was real or not. People wanted it to be real, so it came true in the way knights of the 12th century and later were expected to behave at court, on the battlefield and in tournaments. Men can turn anything into a competition, even and especially trying to act like the heroes of popular stories. This is how chivalry became the overwrought pageantry of a knight attempting to perform the righteous and lionhearted role society wrote him into because of the books they read, like an actor at a renaissance fair playing the part of someone who probably never even existed. Except, you know, using real swords and killing real people. This “New Age” of chivalry lasted around 500 years, until the beginning of the 17th century, when Miguel de Cervantes (a military veteran who’d been wounded in battle, captured and held prisoner of war for nearly five years) comprehensively mocked this culture to death in Don Quixote. Were there knights during the five hundred-year New Age of chivalry who shirked trends and ignored the expectations placed on them by society? Probably. There were certainly knights who never cared about fighting in miniature wars. But knights who did enter tournaments cared about chivalry a lot. Knights entering of their own volition, whether motivated by ego, honor or whatever else, they’d need to be skilled enough in combat to actually win fights. If they’re already doing the hard part, why not lean into the whole chivalry thing and reap the social benefits? Even those with mercenary motives, attracted to the game by money and prizes, would’ve at least had to pretend because any noble family hiring a knight to represent their house would expect displays of chivalry.

So, largely based on 12th century fairy tales about things that never happened a thousand years earlier, knights entering tournaments began advertising their “romantic” dispositions – their commitment to chivalry – by wearing a lady’s favor. This was some visible token of feminine affection. It could be jewelry, though a more typical favor was a kerchief or similar piece of fabric, sewn and embroidered by a woman (or her servant) for this explicit purpose. Because that’s what the women characters did in the fairy tales. In books, the purpose of a lady’s favor varied according to plot. Most often, it was merely to help a knight carry memories of his beloved on long journeys and dangerous quests or to superstitiously provide God with a nominal excuse to give the knight a safe journey home so he could “return the favor.” Sometimes the lady’s favor was meant as a good luck charm or (more commonly, what with the existence of magic in so many of these stories) an enchanted item granting the knight special powers and/or protection. All of these types of favor could be worn under armor to keep them secret and safe. Not so with favors worn in the new age of chivalry to broadcast a knight fought for the love and honor of a lady, especially as her champion to settle some dispute or perceived insult. This was the favor of the tournament and it was to be proudly displayed for all in the audience to see, perhaps even given to the knight in front of the audience, should he request the favor from a lady in attendance upon entering the field of battle. As with most acts of chivalry, the entire point was to be noticed, otherwise the knights and the ladies could’ve kept all this to themselves.

About a hundred years after 12th century literature married romance to chivalry, this performative aspect of the culture shifted the main attraction at tournaments from epic battles held across miles of woods and pastures back into town, to what before was a side event for only the most skilled warriors, considered much too dangerous for young princes and royal heirs to compete. The one rule for this side event was exactly the same: it’s war, except everyone’s a knight. This war even began with a cavalry charge. The only difference is it was scaled down to one-on-one combat – the joust. Now, being part of a cavalry charge and being the cavalry charge are different. Your chances of dying go way up when it’s just you and one other guy charging at each other on horses, aiming long, sharp sticks at each other, as you’ve each practiced doing thousands of times. And if those aren’t high enough stakes for you, keep in mind this whole thing happened right in front of an audience. The larger team and free-for-all battles continued in the fields and those who wished were able to observe the action from a great distance. However, the details of what happened out there were really only learned after the fact, when all the knights came in and told stories of their accomplishments. The joust distilled combat to brute simplicity and gave everyone a front row seat to the action.

And it was only a little safer than one-on-one combat in a real war. Should two knights of warring houses meet in the wild, again, they’d both want to spare the life of the other and capture him as a prisoner, if possible. But this could be accomplished by spearing the other knight’s leg or killing his horse to take him down to the ground. In front of an audience, such an act would be unchivalrous. The victor of a tournament joust was usually determined by tallying the points each knight received for shattering a lance upon the shield or in-bounds armor of his opponent. There were, however, other paths to victory. Directly striking an opponent’s chest armor or helmet was likely to knock him off his horse and unconscious (perhaps even killing him), thereby securing a win. Should the unhorsed knight remain conscious and choose to keep fighting, the battle continued on the ground with blunted swords until one knight or the other surrendered by removing his own helmet. Win or lose, all of this happened directly in front of a crowd, who watched everything as it took place. They weren’t gonna hear about it later. And, just like that, a knight no longer needed to tell his own stories. Because everyone else started telling the story for him.

As You Wish

When George Jones won a Grammy award for “He Stopped Loving Her Today,” one of the things he said in his very brief acceptance speech was, “I just know that we owe so much to the songwriters in the business because they’re the ones that made it possible for me to be in this position tonight. In my case, it’s Curly Putman and Bobby Braddock from Nashville, TN.” Those are two names you’ll see many more times on this podcast because Jones was correct: just as a song is nothing without a singer, a singer is nothing without a song.

Since there are several songwriters to whom it would’ve been appropriate to give an episode in this season, I ran a series of polls on Patreon for supporters of the podcast to determine which writer it would be. Since such polls are usually won by nothing more than name recognition, it would’ve been pointless to list any other names next to Bobby Braddock. So I didn’t. Instead, I made the candidates anonymous by assigning nicknames derived from their personalities, thereby allowing listeners to vote based on the kind of story they’d like to hear. The choice was between the Author, the Natural, the Earner and the Joker.

The Author puts me in mind of stereotypes we have about novelists, always feeling and experiencing life a bit more intensely than everyone else, often at the cost of mental and emotional anguish, consistently striving toward some breakthrough or masterpiece or reinvention of self. The Author has the whole tortured artist/cynical romantic thing going full-throttle, 24/7.

While the act of creation tortures some, the Natural makes it look as effortless as turning on a light switch. The Natural wrote a #1 pop song at least five years before deciding to pursue songwriting as a profession. Many legendary artists returned again and again to the Natural for their material and the hits, country and pop, kept coming, until suddenly quitting the entire business seemed to come as easy as anything else.

More than just a hit songwriter, the Earner was a real go-getter. Not the only writer here who branched out to other areas of the recording industry. Not the only writer here to play a significant role in discovering a major recording artist. These plot points are, however, a much larger part of the Earner’s story due to the degree of success with such endeavors.

The Joker’s nickname is meant more in the “wild card” sense than the “deranged Batman villain” sense because the Joker would probably be just as happy to sit down and plot some huge prank as they’d be to write another hit song. And when a liquid lunch or late night with a bottle could turn into yet another #1 record, it’s pretty easy to justify having a good time. Work hard, play harder.

The Joker is Glenn Sutton. The Earner is Norro Wilson. The Author is Bobby Braddock. You will hear all those names throughout this season and beyond. Today, though, we’re here to talk about the Natural: Dallas Frazier. We will get into why he quit the music business barely ten years after he began writing hit country songs but, in stepping away from the spotlight, Dallas didn’t leave behind much of a story other than the one told by his body of work. Fortunately for us, that happens to be a fascinating story.

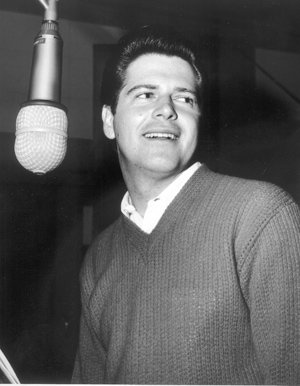

California Cottonfields

Dallas Frazier was born into poverty in Oklahoma in 1939, near the end of the Great Depression. When he was only a few years old, his family moved to California, making them bonafide Okies in the town of Bakersfield, where he grew up. Dallas loved to sing and, being a creative child, he began coming up with his own songs just for fun when he was around ten years old. When he was twelve, he won an amateur talent contest hosted by Ferlin Husky at a Bakersfield dancehall. Ferlin was so impressed, he offered Dallas a job as a backup singer in his band. Dallas accepted and, shortly after, with his parents’ permission, moved into Ferlin’s house for work. He was only fourteen years old when Ken Nelson signed him to an artist contract with Capitol Records, right around the time Dallas got a job singing in the house band of the Cousin Herb Henson’s Trading Post Gang TV show in L.A.

Dallas Frazier (2nd from right) with Herb Henson’s Trading Post Gang

In 1954, the Trading Post band backed up Dallas on his first record for Capitol, Herb Henson’s “Space Command.” This intergalactic fantasy didn’t do much on the a-side and, as is so often the case, young Dallas’ own composition was the b-side of his debut record. The only thing we can do is wonder if Capitol missed the hit with “Ain’t You Had No Bringin’ Up at All.” Much of the intelligence, humor and craft he’d carry through his entire career was already in place on this first recording of a Dallas Frazier composition. As a performer, at fourteen years old he was already confident enough to warp the syllables in words, forcing language to serve his own needs years before everyone would fall in love with Roger Miller for doing the very same thing. When his next couple singles were equally ignored, Capitol released young Dallas from his contract but he continued working with Ferlin Husky, singing on the Trading Post and he joined the cast of Cliffie Stone’s Hometown Jamboree, appearing on L.A. television several times a week for several years and performing alongside the greats of the era, like Tennessee Ernie Ford, Buck Owens, Skeets McDonald and Johnny Horton.

L-R: Dallas Frazier, Tennessee Ernie Ford , Jean Shepard, Tommy Collins

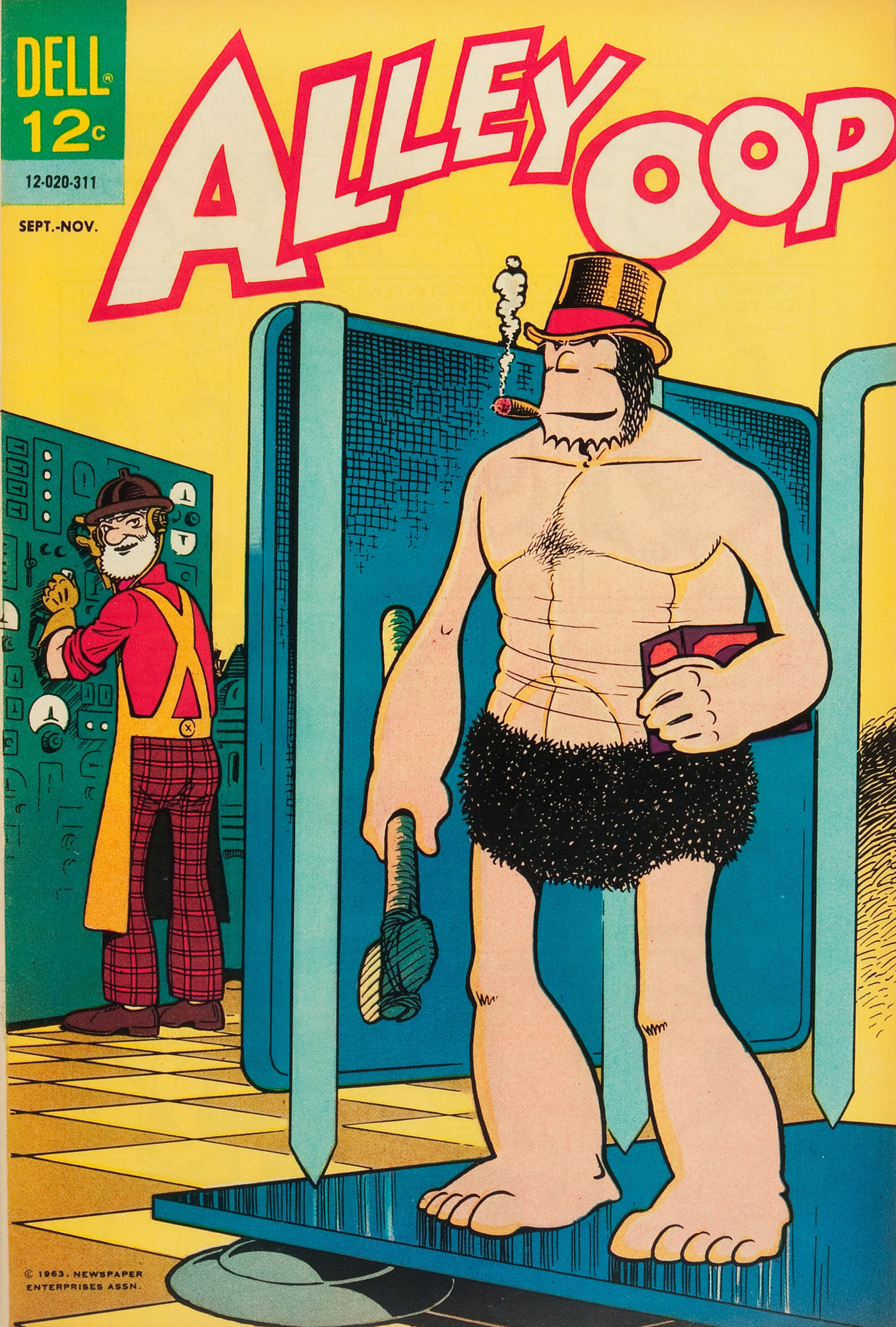

In 1957, when he was about 18 years old, Dallas fell in love with and married a young woman named Sharon. In 1959, a tiny indie label released his next record. Presumably written either prior to meeting Sharon or strictly from imagination, “Can’t Go On” documents Dallas’ maturing voice, as well as his transition to the R&B sound he would keep for most of his recording career. “Can’t Go On” was not a hit. But the next cut of a Dallas Frazier song went #1 pop, #15 pop and #59 pop on three different records at the same time. Dallas wrote the song in 1957, the same year he got married. Even working all those sideman gigs at once didn’t bring in very much money to his household, so Dallas continued taking fieldwork where he could get it, entertaining himself during the hours of manual labor by coming up with songs to sing. On this day he was picking cotton and thinking about the comic strip character, Alley Oop, V.T. Hamlin’s prehistoric caveman from the kingdom of Moo, introduced in 1932 and (as of this recording) still in syndication. Dallas worked his way up and down the rows of cotton while singing about Alley Oop’s wildman adventures and the little ditty must have stuck with him because, in 1960, Gary S. Paxton (of Skip & Flip and, later, “Monster Mash” fame) got a bunch of studio musician friends to record “Alley Oop.” Everyone on the session (including Dallas on background vocals) was allegedly as drunk as it sounds like they were. Released under the name The Hollywood Argyles, this record was a phenomenon, one of those novelty hit sensations nobody could’ve predicted and which still cannot be explained. On its way to #1, it sold over a million copies and spawned several covers, most notably from Dante & The Evergreens, whose record only hit #15 pop in Billboard but Cash Box tracked it as also coming in at #1. The Dyna-Sores’ record going #59 put three versions of the same Dallas Frazier song in the Hot 100 in 1960.

His next single as an artist came out the following year on another little indie label. And his voice sounds great… but there’s not much to “She Made Me Cry” as a composition and the all-out chaos of the arrangement was perhaps a bit much for record buyers who were still a year or two away from shelling out for The Rivingtons’ “Papa Oom Mow Mow” and The Trashmen’s “Surfin’ Bird.”

By the end of 1962, Dallas and Sharon were living in Portland, Oregon. The full reasons for the move are unclear but in a 2012 interview with BronsonsMusic.com, Dallas said he’d “kind of gotten out of the business and all.” Since he and Sharon by this time had some kids and his own records weren’t selling, it seems likely Dallas decided to take the money he made from “Alley Oop” and go try to be a responsible parent instead of a rockstar. However, he was barely in Portland for a year before Ferlin Husky came through on tour. Dallas went to see his old friend and Ferlin asked what he was doing up there, away from all the action. When Dallas said there wasn’t much up there to do, Ferlin talked him into coming to Nashville to write songs for Ferlin’s new publishing company. In late 1963, Dallas once more moved into Ferlin Husky’s house, this time in Nashville, this time bringing his wife and daughters with him and this time Ferlin was in the middle of one of his many divorces. So the Frazier family moved into a place of their own within about six months. In addition to the publishing company, Ferlin Husky owned a gas station, where Dallas took a day job while writing songs on the side. Dallas was still working in the gas station when Ferlin Husky recorded the first country hit on one of his songs, “Timber, I’m Falling” in 1964. On paper, it is a pop song, complete with a baby/maybe rhyme. On record, the strummed banjo and reference to a tree gave Capitol more than enough excuse to ship it to country radio and it wound up charting at #13. Not a bad start to Dallas’ Nashville career.

But Ferlin Husky was then one of the biggest stars in country music and this was only a few years after his “Wings of a Dove” spent ten weeks at #1, nearly breaking into the pop Top 10. So Ferlin was on tour all the time while Dallas was sitting back in Nashville, writing tons of songs that weren’t being recorded or worked by a real publishing company. Ferlin understood the situation and there were no hard feelings when Dallas jumped over to Jim Reeves’ Acclaim Music in late 1964.

Ferlin Husky and Dallas Frazier

The Coolest Guy That Is What Am

Nothing much happened for Dallas at Acclaim until the summer of ’65. Song plugger Ray Baker told Charlie Rich they had a perfect song for Charlie’s recording session the next day. When Ray told Dallas how well the meeting went, Dallas asked which song Ray was talking about and Ray said he figured Dallas would just write one. He did try late into the night but couldn’t come up with anything good, so he set an alarm for 5am, got a couple hours sleep, woke up early in the morning and wrote “Mohair Sam.” Charlie Rich cut the song only hours later in his first session for Smash Records, produced by Jerry Kennedy. That’s Charlie McCoy on one of the hookiest bass intros of all time. When “Mohair Sam” came out as Charlie’s first single on Smash, it hit halfway up the pop Top 40, his first major record since “Lonely Weekends” five years earlier on Sun.

After that, Ray Baker decided to steal Dallas from Jim Reeves and start his own publishing company. They were sitting in a bar one day, drinking beer and thinking up good names for Ray’s new pub. co. when they landed on Blue Crest, the name of an old beer brand from the 1940s. Ray worked with a couple other writers but, according to him, he never had the money to put anyone else on staff, so Blue Crest Music was always pretty much just Dallas Frazier. As soon as he founded Blue Crest, Ray dug through the stack of songs Dallas had written for Ferlin Husky with the understanding he’d split publishing with Ferlin on any unrecorded gems. The song he found has since earned more money than anything else ever written by Dallas Frazier. It was the very first thing he wrote when he came to Nashville…

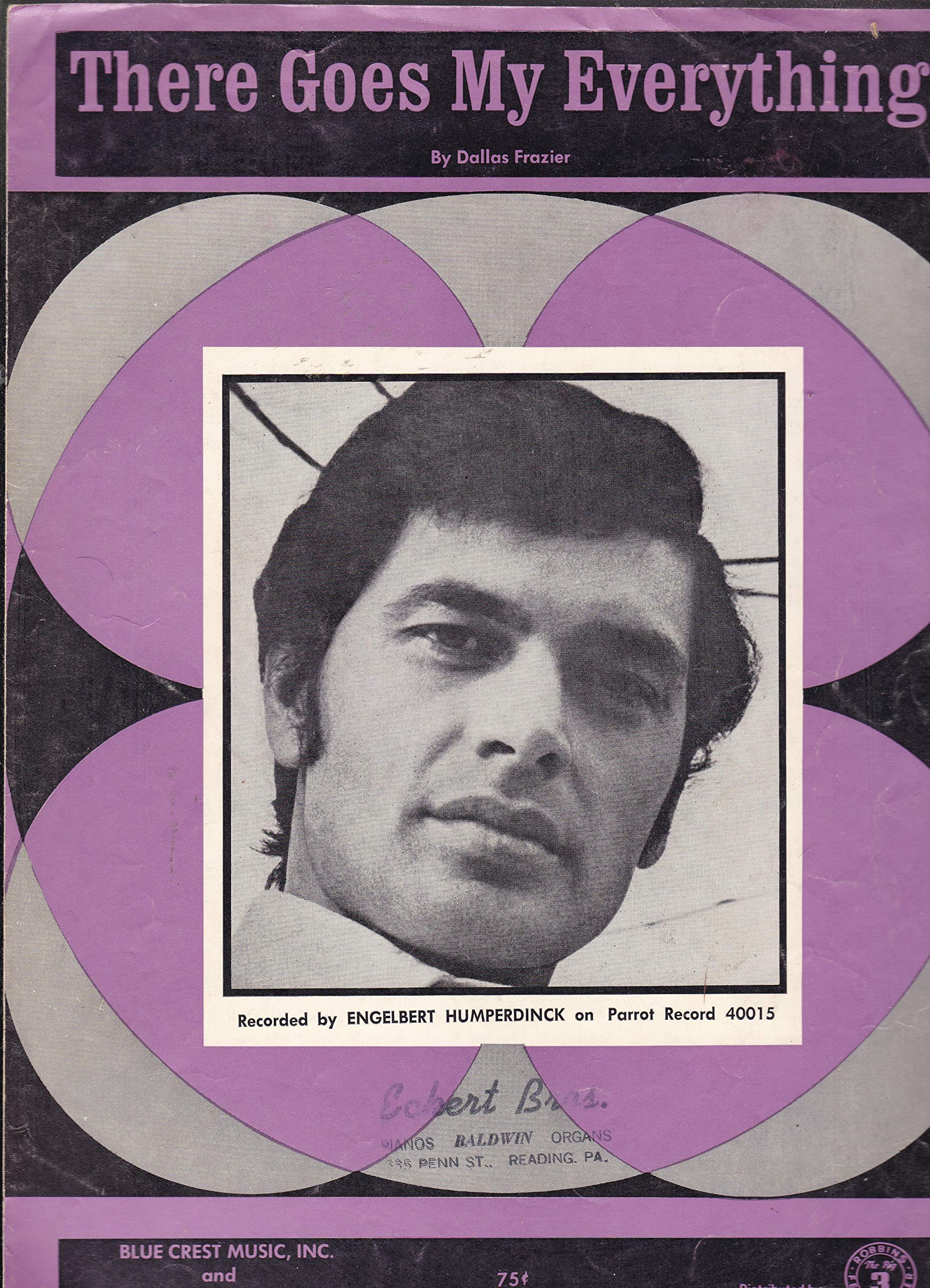

The footsteps referenced at the beginning of “There Goes My Everything” were inspired by the woman Dallas saw leave Ferlin Husky in 1963. Decades later, Dallas told The Tennessean he didn’t put it in the song but, in real life, those footsteps were taking her toward a yellow cab waiting outside. Ferlin was first to cut the song in late 1965 and it came out the following summer. His record didn’t do much but Jack Greene’s wife heard it and convinced her husband to cut the song. Less than two years earlier, Jack Greene was just Ernest Tubb’s drummer. When his version of “There Goes My Everything” (produced by Owen Bradley) came out in late 1966, it became his first major hit, spent seven weeks at #1 on the country chart, made it almost halfway up the pop Hot 100 and created a new genre standard. In 1967, the first year the CMA started handing out awards, they gave “There Goes My Everything” Single and Song of the Year, the album it was on won Album of the Year and Jack Greene won Artist of the Year. By the time all these awards came in at the end of 1967, the song had been covered by country artists Loretta Lynn, Ray Price, The Statler Brothers, Tammy Wynette and George Jones – as well as Del Reeves, Jim Ed Brown, Red Sovine, Wilma Burgess, Kitty Wells, Jimmy C. Newman, The Wilburn Brothers, Jean Shepard and Roy Drusky. Again, those are just the covers that came out within one year of Jack Greene’s record. In the same period, Engelbert Humperdink’s version hit Top 40 radio. It would take way too long to list everyone who has since recorded “There Goes My Everything” because it’s been cut by over 150 artists.

There are hit songs and then there are hit songs that continue to be recorded years and decades after the original hit. “There Goes My Everything” is the second kind of hit song. And that’s the kind Dallas Frazier kept writing. At any point in his career, as he wrote more and more hit songs, there was no telling when a major artist would resurrect something he’d written years earlier for another huge hit single or placement on a top-selling LP. In 1965, The Beach Boys put “Alley Oop” on Beach Boys’ Party!, a Top 10 LP. In 1967, Tom Jones put “Mohair Sam” on the Green, Green Grass of Home LP, which sold half a million copies.

Country Hit Parade

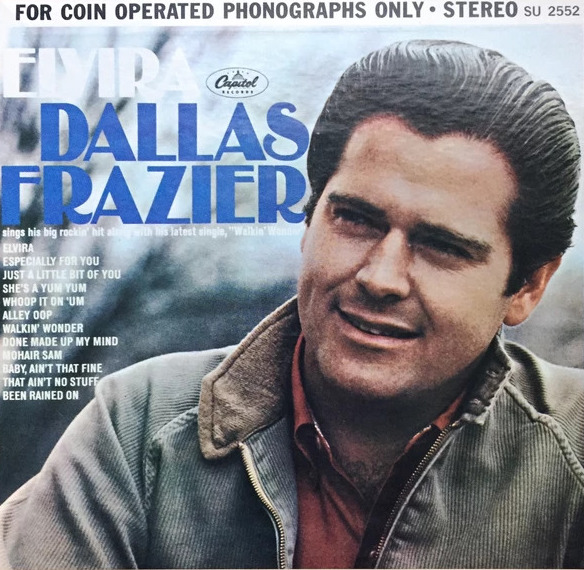

Ferlin Husky got Dallas hooked back up with Capitol Records in 1965. The David Wilkins song “Make Believe You’re Here with Me” didn’t do anything as his first single back. But the title track and lead single of his first Capitol LP made it into the lower half of the pop Hot 100 in 1966. The Elvira in this song is meant to be a woman but this was several years before the Vampira-inspired “Mistress of the Dark” began introducing horror movies on late-night TV and Dallas Frazier’s song wasn’t inspired by any real woman. Rather, he wrote it after driving through East Nashville one day and noticing a sign for Elvira Ave., which he thought was a unique and “funky” name. Before you know it, he had the beginnings of a song about how his heart was “on fire-uh” for Elvira.

Other singles released from his first Capitol LP weren’t as successful but what with Dallas continuing to write massive hits for other artists, the label kept him around long enough to make a second album. And it’s usually pretty interesting to compare Dallas’ versions of his own songs to the versions that became hits for other artists. For one thing, he is a phenomenal singer and easily one of the most soulful hummers in the game, as heard on his version of “Mohair Sam.” But it’s also cool to hear the R&B arrangements he probably had in mind when writing songs which later became hits for country artists. In 1966, Connie Smith took a strings-and-steel-guitar cut on “Ain’t Had No Lovin’” to #2 country. In 1967, on his second Capitol LP, Dallas put down a bass-and-horn-heavy version. We’ve already discussed Melba Montgomery and Gene Pitney performing “Baby, Ain’t That Fine” in a country fashion. Theirs was the first recording and only hit on the song but Dallas’ joyous, horn-filled R&B take is just as compelling. Even though he loved country music, it’s obvious Dallas came to think of himself as more of an R&B singer. Just listen to his version of “Tell It Like It Is” from the same album.

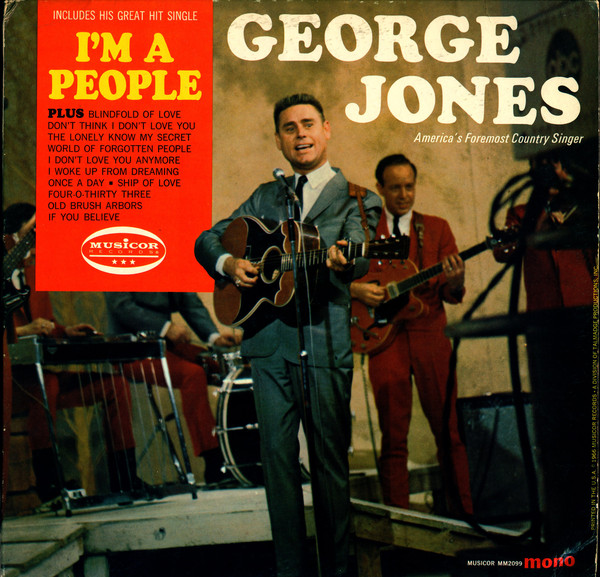

Near the end of 1966, around the time Jack Greene’s “There Goes My Everything” was starting to take off but before anyone realized how monumental of a hit it would be, Pappy Daily bought a 40% stake in Blue Crest Music. This was after Melba & Gene had the hit with “Baby, Ain’t That Fine” and George Jones had already recorded about ten Dallas Frazier songs, so it’s another instance of Pappy finding a way to get in on the action while allowing his artists to keep doing whatever they wanted to do, which was record songs written by Dallas Frazier. One of the Dallas songs George Jones cut prior to this deal was the title track of his 1966 LP, I’m a People. It’s another one of those post-Roger Miller wacky novelty numbers (which, if you haven’t put it all the way together yet, Roger Miller is indirectly responsible for a significant percentage of the worst songs coming out of Nashville during the mid-1960s) but Dallas Frazier was writing wacky novelty hits before anyone ever heard of Roger Miller, so his entries to the field shone brighter than most. The rhyme scheme of “I’m a People” also harkens back to the kind of “talkin’ blues” motifs a young Bob Dylan lifted from Woody Guthrie, here applied to a human being wishing he was a monkey so he wouldn’t have to work or otherwise engage in foolish social endeavors. “I’m a People” was a Top 10 country record in 1966. Perhaps of more enduring quality, the next song on the album was also written by Dallas Frazier. Recorded in June 1965, Johnny PayCheck was still playing bass for the Jones Boys and it’s almost certainly his husky voice in the background of “Don’t Think I Don’t Love You.”

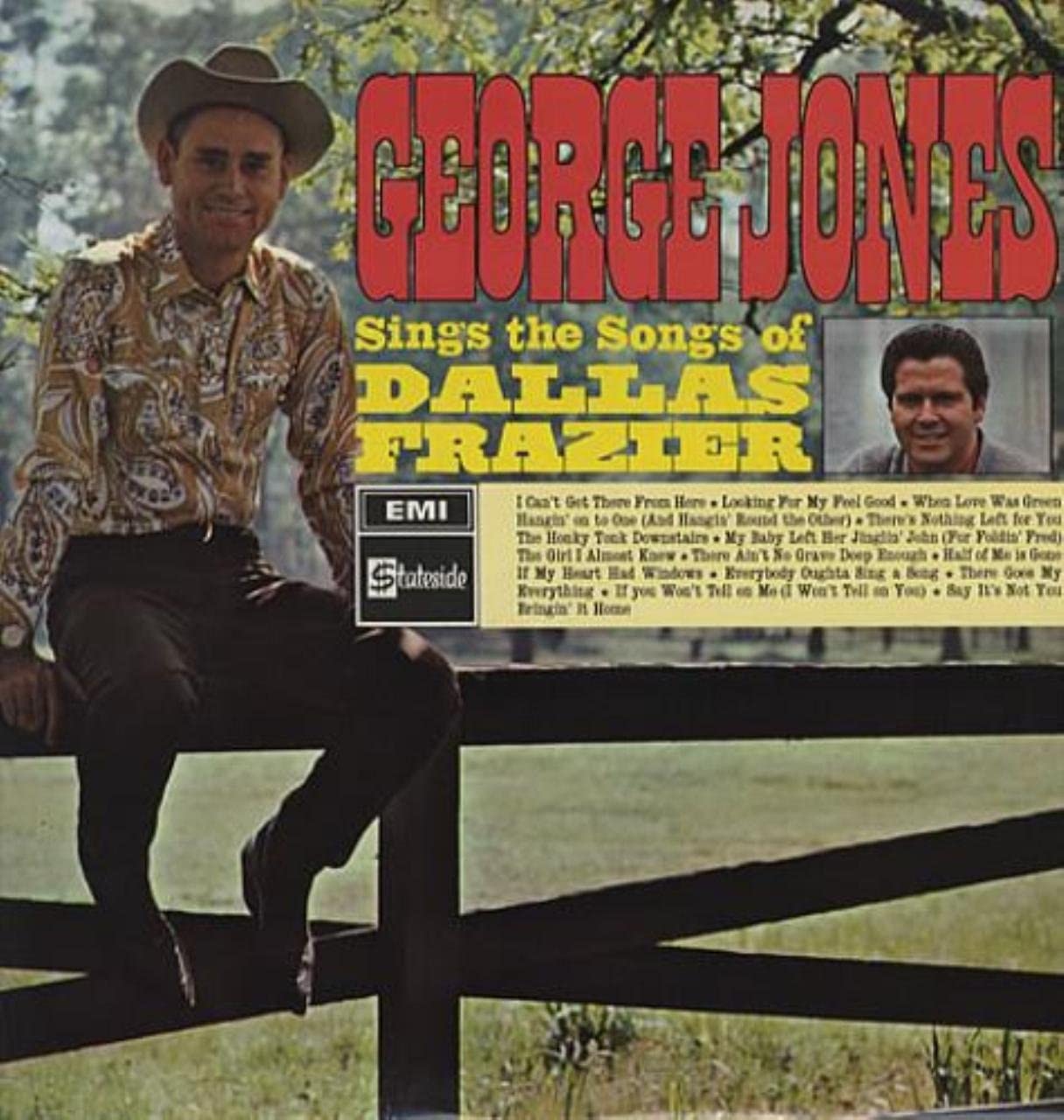

It looks like Pappy Daily’s deal with Blue Crest went into effect in January of 1967, as there’s an exponential increase to the number of Dallas Frazier songs in George Jones’ recording sessions just prior to then. His next a-side written by Dallas was a non-album single selected from a session of nothing but Frazier compositions. After “I Can’t Get There from Here” went Top 5 Country, Jones’ next single was also written by Dallas Frazier. After “If My Heart Had Windows” went Top 10 Country, Jones’ next single (recorded in the same session) was also written by Dallas Frazier and also went Top 10 Country. Since “Say It’s Not You” and “If My Heart Had Windows” were two of the eleven Dallas Frazier songs Jones recorded during two sessions in June 1967, it’s safe to assume Pappy Daily decided those songs were too good to put on the 1968 LP, George Jones Sings the Songs of Dallas Frazier.

Aside from Pappy throwing “I Can’t Get There from Here” on the tracklist as the first song, there were no new singles released from this album but there is also 0% filler. I can say without hesitation this is my favorite George Jones album from beginning to end. This is Jones right in the sweet spot, both vocally and in terms of late ‘60s Nashville Sound production. There isn’t much information available on which A-Team musicians worked the sessions but the pedal steel guitar sounds to me like Lloyd Green and everything he does is masterful. After opening with its lone hit, the album moves into “Lookin’ for My Feel Good,” which kicks off with a frantic, daddy-long-legs guitar part doubled on two electrics while the piano rolls out a similar riff on the low end. As the second verse starts, one of the guitars gets even more frantic, what with Jones still not finding his “feel good.” After that, it’s time for a sad one. On “When Love Was Green,” the pedal steel strings get raked back and forth while Jones rakes through his past for memories of better days. In “Hangin’ on to One (And Hangin’ ‘Round the Other),” Jones can’t give up on his wife or his mistress, which makes for a sticky situation he knows sure isn’t gonna end well and The Jordanaires sound like the bar full of friends he’ll be hanging out with when the whole thing blows up. “Half of Me Is Gone” is an uptempo heartbreak song in which Jones paces the floor of his room, never outpacing the pain. If “The Honky Tonk Downstairs” came out as a single ten years later, after Jones’ on-record persona became synonymous with hopeless alcoholism, it would likely have been a major hit. Here, it’s a preview of things to come. A title like “My Baby Left Her Jinglin’ John (For Foldin’ Fred)” could easily be a swing and a miss on another goofy heartbreak song but Dallas Frazier’s “big money man vs. little money man” imagery immediately sells and never gets bogged down in the concept. The title of “The Girl I Almost Knew” looks like another Cowboy Jack rewrite of “She Thinks I Still Care.” Then you press play and it’s a no-tricks, no-frills, never-gonna-fix-this-broken-heart excuse for Jones to, as Pig Robbins would put it, “moan his ass off.” There’s quite a bit of baritone guitar all over this album but that deep tone is used to most dramatic effect when kicking off “There Ain’t No Grave Deep Enough,” one of those “you left me but I’d always take you back” tracks Jones turned into hit after hit during these Musicor years. And, finally, the album closes on “There’s Nothing Left for You,” showing things have only gotten worse since earlier, when only half of Jones was gone. After the Dallas Frazier LP came out, Pappy Daily packaged “If My Heart Had Windows” as the title track of Jones’ next album, which also featured “Say It’s Not You” and two more Dallas songs. George Jones recorded somewhere around 50 Dallas Frazier songs in the seven years he was on Musicor, so we won’t have time to look at them all.

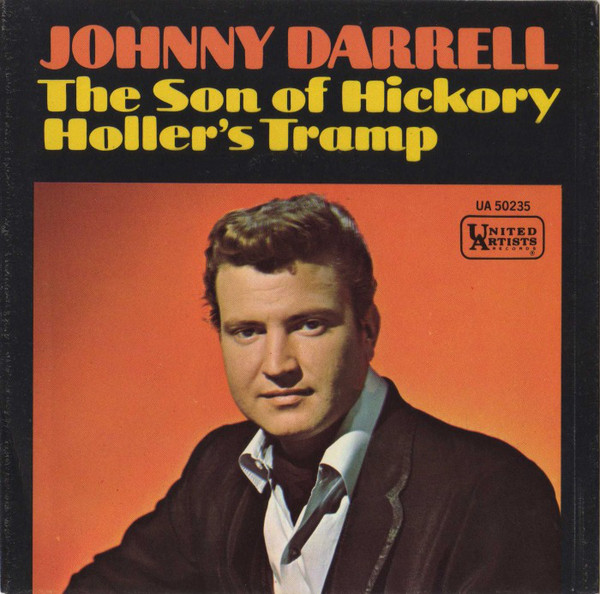

In 1968, Dallas took a little vacation to Florida and came back with “Until My Dreams Come True,” another #1 country song for Jack Greene. There are few higher compliments a country songwriter could receive than Merle Haggard, one of the genre’s greatest singer-songwriters, choosing to record one of your songs. Merle’s 1968 album The Legend of Bonnie & Clyde featured three Dallas Frazier songs: “Love Has a Mind of Its Own,” “The Train Never Stops” and the Charlie Louvin hit “Will You Visit Me on Sundays?” But Dallas’ greatest commercial success of 1968 was definitely “The Son of Hickory Holler’s Tramp,” which is about exactly what it sounds like it’s about: being the forever grateful child of a one-woman red light district in a backwoods town. This is Dallas’ favorite song he ever wrote and it’s one of several great songs – like “Green, Green Grass of Home,” “With Pen in Hand,” “Willing” and “Why You Been Gone So Long” – which country singer Johnny Darrell was first to record only to watch other artists cut the same song to much greater success. Johnny’s late 1967 record on “The Son of Hickory Holler’s Tramp” did make it about halfway up the country Top 40 and this recording of the song was soon followed by Sanford Clark, Merle Haggard, Del Reeves, Nat Stuckey and Bobby Bare. But it was O.C. Smith’s R&B version in 1968 that hit the pop Top 40 in the U.S., #3 in Australia and #2 in the UK.

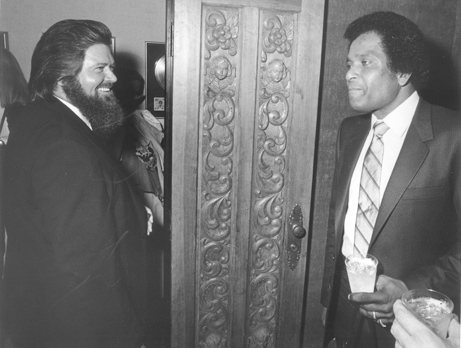

L-R: Lewis Talley, Dallas Frazier, Merle Haggard, Darrell McCall

Everybody Oughta Sing a Song

In 1944, Louis Jordan’s “Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby” hit #1 on Billboard‘s “Folk” chart, as did The King Cole Trio’s “Straighten Up and Fly Right.” And after Billboard came up with the R&B and Country & Western charts in the late 1940s, there was not another record by a Black artist to go #1 country until Charley Pride’s “All I Have to Offer You Is Me” in 1969. The song was written by Dallas Frazier and “Doodle” Owens, who was born and raised in Waco, TX, then came to Nashville, where he soon met and began writing songs with Dallas in the mid-’60s. His first notable co-write with Dallas was “Johnny One Time,” a warning about the love-em-and-leave-em title character, recorded and released as a single by Willie Nelson in 1968. Willie’s record was a minor country hit, leading to several great covers of “Johnny One Time” from Brenda Lee, Loretta Lynn and Melba Montgomery. In January and February 1969, Elvis Presley recorded two Frazier/Owens songs for the From Elvis in Memphis LP, regarded by many fans as his return to serious musical output after years of mostly releasing soundtrack albums for his awful movies. If Elvis sounds like he had a cold on album opener “Wearin’ That Loved on Look,” it’s because he did. The other Frazier/Owens song, “True Love Travels on a Gravel Road,” came pretty deep into side two of the LP. Neither track was selected as a single but the album shipped over 250,000 units upon release and went gold in less than a year. From Elvis in Memphis came out the same month Charley Pride released “All I Have to Offer You Is Me.” It wasn’t his first hit – Charley’s previous seven singles were all Top 10s, beginning with “Just Between You and Me” in 1966 – but it was his first #1 and the first of four #1s written by Dallas Frazier and Doodle Owens. The second was Charley’s next single, “(I’m So) Afraid of Losing You Again.” Following two more #1 records, Charley released another Frazier/Owens song, “I Can’t Believe That You’ve Stopped Loving Me,” featuring a prominent steel guitar part from Lloyd Green. This record went #1 in 1970.

Dallas Frazier with Charley Pride

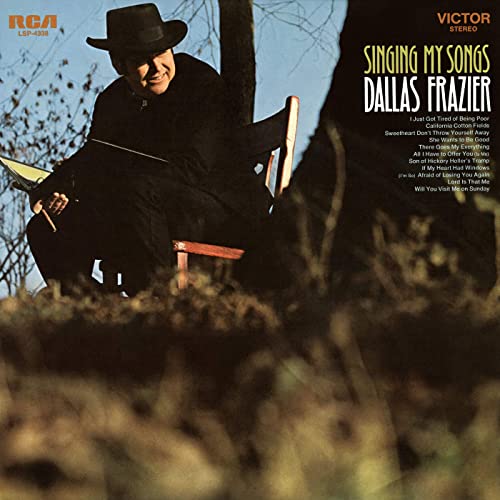

Also in 1970, Dallas Frazier released his third album. After his second LP was largely ignored, Capitol did release a few more singles. “Everybody Oughta Sing a Song” in 1967 was the closest thing he ever had to a country hit, charting at #28. George Jones and Melba Montgomery covered it as an album track the same year. Dallas’ next three singles came close to making the country Top 40 but none of them did. “I Hope I Like Mexico Blues,” written with Doodle Owens, is a great song title and the record follows all the way through. But it evidently fell through the cracks at country radio. I’ve never found a copy of Dallas’ “The Conspiracy of Homer Jones” but Bobbie Gentry must have gotten her hands on one because she cut the song in 1969, though it went unreleased until The Girl from Chickasaw County box set came out about a year after her episode in Season 1. With his singles receiving very little attention, Capitol released Dallas from his contract and he moved over to RCA for his third album, Singing My Songs.

As you’d guess from the title, the idea was for Dallas to record versions of the big hits he’d written for other artists. Since most of those were country hits, this album marks his jump back over to the country side of the genre fence with plenty of Nashville Sound strings and steel guitar in the arrangements, beginning with the leadoff track, “There Goes My Everything.” The album includes two of the hits he and Doodle Owens wrote for Charley Pride. First, “All I Have to Offer You Is Me.” Then, “I’m So Afraid of Losing You Again.” The year before, “Lord Is That Me” was a minor hit for Jack Greene and it was prescient for Dallas to take on this subject matter, since he’d soon begin studying to become a preacher. Dallas wrote “Lord Is That Me” with Whitey Shafer, who got his start in Nashville being underpaid by Ray Baker at Blue Crest, writing with Dallas, “Doodle” Owens and on his own. Many of you have heard George Jones sing Whitey’s song “Between My House and Town,” the second track on Jones’ If My Heart Had Windows LP. Dallas Frazier recorded “If My Heart Had Windows” on this third album… (As his live performances of this song usually begin with a dedication to his wife, it’s worth mentioning here that Sharon was always the inspiration for Dallas’ “true love” songs.) As many great recordings as there are of “Son of Hickory Holler’s Tramp,” the arrangement on Dallas’ version stands apart from the crowd. And the arrangement for his cut of “Will You Visit Me on Sundays?” leans heavier on the strings than most. When Dallas recorded “California Cottonfields” (written with Peanutt Montgomery), he had every reason to assume it would be a hit record by the time this album came out because Merle Haggard put it to tape a few months earlier, in April 1969. But then, for whatever reason (probably “Okie from Muskogee” coming out in the fall of ’69 and changing the trajectory of his entire career), Merle’s version of “California Cottonfields” was shelved until 1971, making the Dallas Frazier recording the first to be released. The only other songs on this album which weren’t already hits for other artists were “She Wants to Be Good,” “Sweetheart, Don’t Throw Your Love Away” and “I Just Got Tired of Being Poor.” I’d suggest the first verse of this last one may have been written from autobiographical experience but I would never accuse Dallas Frazier of stealing candy when he was a little boy. It’s possible Dallas did “I Just Got Tired of Being Poor” because here, too, he had reason to believe it would be a hit by the time his album came out, as George Jones recorded the song in 1969. It went unreleased until 1972, after Jones moved to Epic and Musicor started issuing whatever they had in the vault.

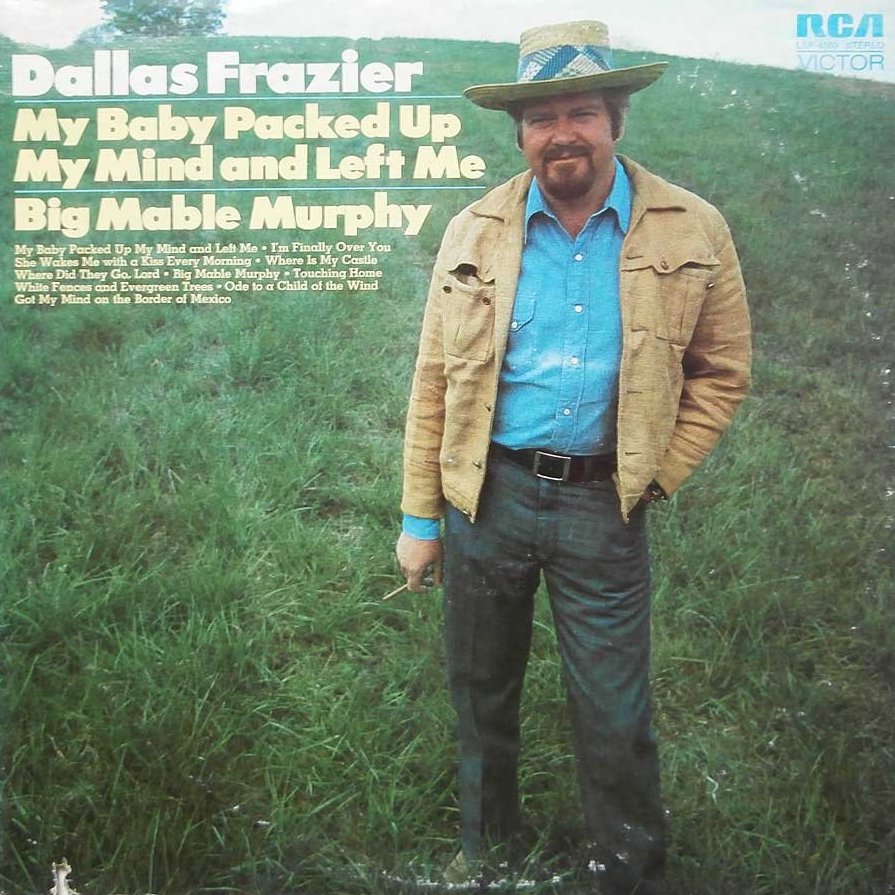

In 1971, the only new hit Dallas wrote (with “Doodle” Owens) was “Touching Home,” a Top 5 country record for Jerry Lee Lewis. However, 1971 was still a very lucrative year for Dallas Frazier because it’s the year Elvis Presley had a Top 10 country record with “There Goes My Everything.” Though it was initially a flop that only began selling after Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars was a hit the following year, David Bowie’s Hunky Dory came out in 1971 and included “Life on Mars?,” now one of his most well-known songs, containing a direct reference to Frazier’s “Alley Oop” in the lyric “look at those cavemen go.” 1971 was also the year RCA released their second and final Dallas Frazier LP. This time he recorded a few of his hits written for other artists; like the Jerry Lee Lewis record “Touching Home;” “Where Did They Go, Lord?,” which charted in the pop Top 40 as an Elvis Presley b-side earlier in the year; and “Where Is My Castle?,” which just missed the country Top 10 for Connie Smith in 1970. But My Baby Packed Up My Mind and Left Me wasn’t a rehash of the previous LP’s concept and features many more original recordings, like the title track and the jazzy “Big Mable Murphy,” yet another Dallas Frazier single which barely missed the country Top 40.

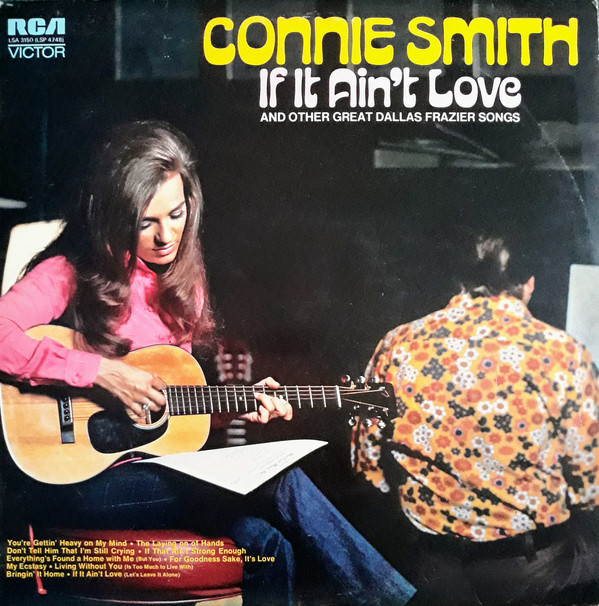

In 1972, Connie Smith became the second country artist to release an entire album of Dallas Frazier compositions, called “If It Ain’t Love” and Other Great Dallas Frazier Songs. Other than “Where Is My Castle,” Dallas also wrote Connie’s Top Ten 1968 record, “Run Away Little Tears,” and (with Doodle Owens) her Top Five 1972 record, “Just for What I Am.” In total, Connie Smith recorded somewhere around 70 songs written by or with Dallas, which is even more than George Jones. While the songs and arrangements on her Dallas Frazier LP are not as uniformly excellent as Jones’ entry to this small field, there’s a reason Jones often said Connie Smith had the best voice of any woman in country music and her album does have several high points. The title track and lead single went Top 10 country because it’s one of the greatest “don’t mess with my body if you don’t want my heart” numbers in the genre. “Living without You” and “Don’t Tell Him That I’m Still Crying” are two of Dallas’ best heartbroken weepers and Connie hooks both all the way home. Speaking of home, “Bringin’ It Home” is one of three songs on the album to feature Dallas as a guest vocalist. You’ll note Christianity becoming an increasingly common theme in his writing and, perhaps not coincidentally, Connie Smith’s albums also began featuring more gospel material in this period.

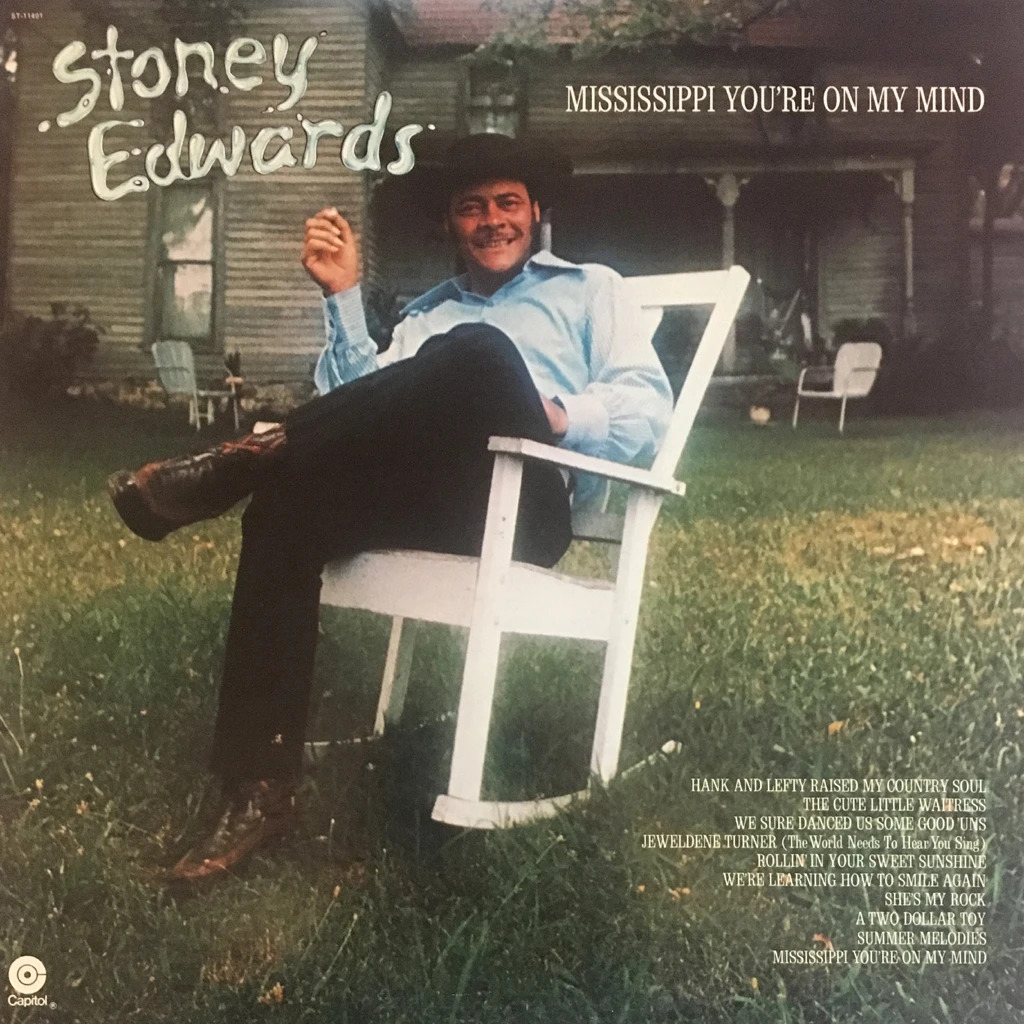

In 1973, Stoney Edwards had a small country hit with “Hank and Lefty Raised My Country Soul,” written by Dallas Frazier and Doodle Owens to be the kind of lionizing anthem you’d expect from the title. The words “country soul” have often been interpreted as a sly reference to the country soul sub-genre of music but anyone who’s actually listened to it knows this is a misunderstanding. As you can hear, he was hardcore country, through and through. In the United States in the 1970s, Stoney Edward’s Irish, Black and American Indian genealogy tracked as simply “Black.” Stoney once told Peter Guralnick, “I was never really accepted by any race. Sometimes I wished I was black as a skillet or white as a damned sheet, but the way I am it’s always been a motherfucker.” After “Hank and Lefty Raised My Country Soul” came out and made at least enough noise for everyone in Nashville who actually gave a shit about country music to pay attention, Stoney happened to find himself in the same bar as Lefty Frizzell one night. Lefty was only two years away from successfully drinking himself to death and, on this night, when someone played “Hank and Lefty Raised My Country Soul” on the jukebox, Lefty was so drunk he couldn’t hold back the tears from hearing the song and so drunk he didn’t have a clue who he was talking to when Stoney Edwards walked up to introduce himself as the singer. After spending the past decade or so feeling like the industry and country music fans forgot about him and moved on, Lefty was blown away by the tribute to him. But then he expressed some kind of frustration over the record being by a Black artist. Only, Lefty used the n-word. Stoney just shook his hand and walked away.

Straighten Up and Fly Right

In late 1972, Dallas Frazier and Peanutt Montgomery wrote “What’s Your Mama’s Name, Child” and Bobby Bare was the first artist to record it. But Tanya Tucker’s version of the song came out first, in February 1973. This was Tanya’s first #1 record and the title track of her second album, which also included a killer version of “California Cottonfields.” Later in 1973, Jeannie C. Riley was the first artist to release a version of “The Baptism of Jesse Taylor,” though only as an album track. By the time he wrote this song with Whitey Shafer, Dallas was at least thinking about becoming a preacher, if not already studying in earnest. (Whitey’s mom had him singing gospel music back in Texas when he was only six years old and this background is probably why Dallas chose to write so many Christian-themed songs with him in this period.) The same month Jeannie C. Riley’s album came out, Johnny Russell released “The Baptism of Jesse Taylor” as a single and it hit #14 on the country chart. Within months, the song was recorded by George Jones, Tanya Tucker, and The Oak Ridge Boys. The Oak Ridge Boys’ cut was not a commercial hit but it did win a Grammy award for Best Gospel Performance.

The Oak Ridge Boys with Dallas Frazier

By 1974, Dallas’ output had significantly slowed, as he’d begun to seriously consider getting out of the music business. His only hit of the year was another #1 for Charley Pride, again written with “Doodle” Owens, “Then Who Am I?” This is a heartbroken love song but the question in the title is basically what Dallas was asking himself more and more often. Was he a good, Christian husband and father? Or was he an alcoholic who wrote songs about drinking and cheating? Was it even possible to serve the Lord while working in secular country music, let alone participating in the barroom culture where so many gears of the business were turned? He wasn’t so sure. Released in 1974, “Champagne Ladies and Blue Ribbon Babies” by Dallas Frazier and Doodle Owens was one of Ferlin Husky’s final charting singles. In 1975, Moe Bandy nearly had a Top 10 hit with “Don’t Anyone Make Love at Home Anymore?,” written by Dallas Frazier.

In 1976, his spiritual struggle having only grown more intense, Dallas decided to take a one year break from the industry, thus entering a thirty-year period during which he was “practically retired.” Even being inducted to the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1976 wasn’t enough to keep him in the business.

However (as previously mentioned), if they’re good enough, a writer’s songs don’t stop working just because he does. In December 1976, Johnny Russell released “The Son of Hickory Holler’s Tramp” as a single. While Johnny’s record would eventually hit the country Top 40, most people who know this song know it from Kenny Roger’s platinum-selling second solo album, his first major success after leaving The First Edition. The rest of the decade was a relatively quiet time for Dallas Frazier compositions. At some point in the middle of the ‘70s, bootleggers started passing around a more complete collection of Bob Dylan’s late ‘60s basement recordings with The Band and everyone got to hear his take on Dallas Frazier’s “Baby, Ain’t That Fine.” That this tape even exists means Dylan must have heard either the Melba Montgomery & Gene Pitney version or the Dallas Frazier version, as those are the only two prior recordings of the song from anyone other than some guy in Iowa named Bobby Hankins, who I doubt Dylan ever heard of.

As the ’70s came to an end, some strange cosmic alignment brought three different Dallas Frazier songs off of old tapes and to the top of the charts within a two year period. The first version of “Beneath Still Waters” to see the light of day was by Carl Vaughn in October of 1968. But George Jones was the first person to record the song a full year earlier in September 1967, which is significant because the melody of “Beneath Still Waters” bears a strong resemblance to “Walk Through This World with Me,” Jones’ big #1 hit from earlier in the year. His cut of “Beneath Still Waters” was never released as a single. The way Emmylou Harris heard the song was through that circle of friends who made their own personal George Jones greatest hits collections and she put the song on her 1979 album, Blue Kentucky Girl. When it was released as a single in January 1980 it went #1 country. A little over a year later, in March 1981, The Oak Ridge Boys released “Elvira” as a single. It went #1 country, #5 pop, won their fifth Grammy award, won Single of the Year at the CMAs and sold over two million copies… despite them ruining the entire thing by failing to sing “my heart’s on fire-uh for Elvira” the way Dallas did on the original recording. Okay, I’m only kidding. But it is kind of strange The Oak Ridge Boys didn’t sing “fire-uh” because they picked up the song from Rodney Crowell’s 1978 version, which has a slower tempo that makes it even more blatant when he leans all the way into the “fire-uh.” Knowing Rodney’s dedication to studying the history of his craft, it’s pretty likely he got the song from Dallas Frazier’s original cut rather than the 1970 album version by The First Edition but – for those keeping score at home – yes, Kenny did choose to sing “fire-uh” like Dallas. Six months after The Oak Ridge Boys released the biggest record of their career, Gene Watson released the biggest record of his career, “14 Carat Mind,” written by Dallas Frazier and Larry Lee Favorite. Maybe Emmylou Harris taking “Beneath Still Waters” to #1 made Dallas want to write some more songs or perhaps he figured there was a way to sneak anti-materialism messages into secular music the way he and Larry did on “14 Carat Mind.” But Dallas did come out of retirement to write this song and sing on the demo tape. He was still using an old reel-to-reel recording unit to make his demos, so Gene Watson almost didn’t even listen to it when going through a box of cassettes. But it was the last thing in the box and he hadn’t heard anything he liked so far, so Gene went and hooked up an old reel-to-reel player and listened to the tape. He knew he was gonna do the song before Dallas was even all the way through the first verse and long before Pig Robbins played one of the greatest piano hooks ever on the session. This was Gene Watson’s only #1 record but it didn’t bring Dallas all the way back to the business. Neither did Patty Loveless having her first Top 10 record with “If My Heart Had Windows” in 1987.

During his thirty-year retirement, Dallas did serve as a minister at various times. His longest run at one pulpit was from 1999 to 2006, as the pastor of a non-denominational church in White House, TN, outside of Nashville. After stepping down from this role in ’06, Dallas said he felt the Lord finally telling him it was okay to work in country music, that it didn’t have to be one or the other, and he got back into giving occasional performances, like his 2009 appearance on The Marty Stuart Show. (For everyone who doesn’t know, in 1997 Marty Stuart married Connie Smith, who I’m pretty sure has recorded more Dallas Frazier songs than anyone on the planet, so it’s safe to assume Marty was pretty stoked about having Dallas as a guest on his show.)

Dallas Frazier still pops up here and there to sing some of his songs every now and then. As of this recording, his most recent album is 2011’s appropriately titled Writing and Singing Again, which includes “The Carousel Girl.”

Thank you for reading Cocaine & Rhinestones. Every episode is written by me, Tyler Mahan Coe. There were a lot of songs covered in this one. As always, I encourage everyone to go listen to those full songs because there’s always a lot more to the story there. That’s why every blog post contains a full list of all the songs discussed, in the order they appear in the episode along with links to buy those songs if they’re available to purchase online.

While you’re on the website, please swing by the Support page to see the various ways you can help me keep making more seasons of this show. For a long time, the only way to contribute was Patreon and that’s still my preferred method because it’s the most consistent. But, in order to remain independent, I’ve added several more options to support the podcast, everything from official merchandise to a wishlist of research materials to a simple PayPal account. Those of you contributing are the only reason I’m able to do this and I sincerely appreciate each of you.

This was mostly a really fun episode to make. It’s pretty evident I’m a huge Dallas Frazier fan, as just about anyone who loves music would have to be. Any of the songwriters included in those Patreon polls would have fit right into what I’m doing here but I was glad when Dallas Frazier won because his story is such a perfect piece of contrast to the main arc of the season. Here’s a man who questioned whether the industry and culture built around creativity such as his was actually good for his health and happiness or that of his loved ones, walked away for several decades and only came back on his own terms. That’s admirable and rare.

I should say it’s important to me that people enjoy this show the first time through. Some of you only read the story once and, if you’re still here, that means you’ve accepted there will be moments where you’re not really sure why I’m talking about something, then that thing comes back around later and it makes sense. However, I’m also aware these are stories most fans will revisit multiple times, so I try to create a similar experience across the whole season for those of you going back through a second or third time. I get the feeling nearly everyone is up to speed on what’s happening here but if anyone out there is still confused regarding, say, why I talked so much about bullfighting, this would be a great point to go back and start the season over from the beginning. You could think of this Dallas Frazier episode as a divider between Act 1 and Act 2. I’m not done answering all the questions I’ve raised and all these threads will continue popping out through the final episode of the season but there are a lot of answers waiting to be found in going through just these first 8 episodes a second time.

When the podcast returns in a couple weeks, we’re gonna get the ball rolling on Act 2, which means bringing Tammy Wynette to center stage.

-TMC

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [with links to purchase or stream where available]:

- Dallas Frazier – “Ain’t You Had No Raisin’ Up at All” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “Space Command” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “Can’t Go On” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Hollywood Argyles – “Alley Oop” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dante & The Evergreens – “Alley Oop” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Dyna-Sores – “Alley Oop” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “She Made Me Cry” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ferlin Husky – “Timber I’m Falling” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Charlie Rich – “Mohair Sam” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ferlin Husky – “There Goes My Everything” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jack Greene – “There Goes My Everything” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Loretta Lynn – “There Goes My Everything” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ray Price – “There Goes My Everything” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Statler Brothers – “There Goes My Everything” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tammy Wynette – “There Goes My Everything” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “There Goes My Everything” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Beach Boys – “Alley Oop” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom Jones – “Mohair Sam” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “Make Believe You’re Here with Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “Elvira” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “Mohair Sam” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Connie Smith – “Ain’t Had No Lovin'” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “Ain’t Had No Lovin'” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “Baby, Ain’t That Fine” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “Tell It Like It Is” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “I’m a People” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Don’t Think I Don’t Love You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “I Can’t Get There from Here” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “If My Heart Had Windows” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Say It’s Not You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Lookin’ for My Feel Good” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “When Love Was Green” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Hangin’ on to One (And Hangin’ Round the Other)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Half of Me Is Gone” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “The Honky Tonk Downstairs” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “My Baby Left Her Jinglin’ John (For Foldin’ Fred)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “The Girl I Almost Knew” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “There Ain’t No Grave Deep Enough” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “There’s Nothing Left for You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jack Greene – “Until My Dreams Come True” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Merle Haggard – “Will You Visit Me on Sundays?” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Darrell – “The Son of Hickory Holler’s Tramp” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- O.C. Smith – “The Son of Hickory Holler’s Tramp” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Louis Jordan & His Tympany Five – “Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby?” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The King Cole Trio – “Straighten Up and Fly Right” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Charley Pride – “All I Have to Offer You (Is Me)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Willie Nelson – “Johnny One Time” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Brenda Lee – “Johnny One Time” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Loretta Lynn – “Johnny One Time” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Melba Montgomery – “Johnny One Time” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Elvis Presley – “Wearin’ That Loved On Look” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Elvis Presley – “True Love Travels on a Gravel Road” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Charley Pride – “(I’m So) Afraid of Losing You Again” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Charley Pride – “I Can’t Believe That You’ve Stopped Loving Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “Everybody Oughta Sing a Sing” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones & Melba Montgomery – “Everybody Oughta Sing a Sing” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “I Hope I Like Mexico Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “The Conspiracy of Homer Jones” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “There Goes My Everything” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “All I Have to Offer You (Is Me)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “(I’m So) Afraid of Losing You Again” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “Lord, Is That Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Between My House and Town” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “If My Heart Had Windows” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “The Son of Hickory Holler’s Tramp” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “Will You Visit Me on Sunday” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Merle Haggard – “California Cottonfields” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “California Cottonfields” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “I Just Got Tired of Being Poor” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “I Just Got Tired of Being Poor” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jerry Lee Lewis – “Touching Home” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Elvis Presley – “There Goes My Everything” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- David Bowie – “Life on Mars?” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Elvis Presley – “Where Did They Go, Lord” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Connie Smith – “Where Is My Castle” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “My Baby Packed Up My Mind and Left Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “Big Mable Murphy” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Connie Smith – “If It Ain’t Love (Let’s Leave It Alone)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Connie Smith – “Living Without You (Is Too Much to Live With)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Connie Smith – “Don’t Tell Him That I’m Still Crying” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Connie Smith & Dallas Frazier – “Bringin’ It Home” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Stoney Edwards – “Hank & Lefty Raised My Country Soul” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobby Bare – “What’s Your Mama’s Name, Child” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tanya Tucker – “What’s Your Mama’s Name, Child” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tanya Tucker – “California Cottonfields” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jeannie C. Riley – “The Baptism of Jesse Taylor” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Russell – “The Baptism of Jesse Taylor” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “The Baptism of Jesse Taylor” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tanya Tucker – “The Baptism of Jesse Taylor” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Oak Ridge Boys – “The Baptism of Jesse Taylor” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Charley Pride – “Then Who Am I?” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ferlin Husky – “Champagne Ladies and Blue Ribbon Babies” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Moe Bandy – “Don’t Anyone Make Love at Home Anymore” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Russell – “The Son of Hickory Holler’s Tramp” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Kenny Rogers – “The Son of Hickory Holler’s Tramp” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bob Dylan – “Baby, Ain’t That Fine” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Carl Vaughn – “Beneath Still Waters” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Beneath Still Waters” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Emmylou Harris – “Beneath Still Waters” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Oak Ridge Boys – “Elvira” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Rodney Crowell – “Elvira” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The First Edition – “Elvira” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Gene Watson – “14 Carat Mind” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Patty Loveless – “If My Heart Had Windows” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dallas Frazier – “The Carousel Girl [Amazon / Apple Music / Dallas Frazier’s Site]

Excerpted Video

These videos were excerpted in the episode. For any number of reasons, YouTube may remove them in the future but here they are for now:

Commentary and Remaining Sources

I should mention most of the photos in this post pertaining to Dallas Frazier came from his official website. Naturally, anyone who enjoyed this episode should go spend some time poking around over there.

Okay, I gotta get outta here but come back in two weeks to meet Virginia Wynette Pugh and hear how she became Tammy Wynette.