In North Carolina, way back in the hills, there’s a centuries-old tradition of cooking illegal liquor. Whether you feel that’s right or wrong, good or bad, may be determined by any number of factors but the objective truth is moonshine whiskey greatly impacted the course of United States culture on several occasions. Ever wonder why so many people will never trust the government or politicians? Press play. Ever wonder if the “moonshine” you can now buy in liquor stores is really moonshine? Press play. “White Lightning” was George Jones’ first #1 country record, sure, but it’s also the cork in a jug of profoundly strong history.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

In addition to The Main Library and the Season 2 Library, these books were used for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

As part of my agreement with Simon & Schuster to publish a book adaptation of Season 2, the transcripts that have been freely available for over a year will be temporarily removed from this website. Please consider ordering a copy of Cocaine & Rhinestones: A History of George Jones and Tammy Wynette through your favorite local bookstore or requesting that your local library order a copy you can check out.

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [with links to purchase or stream where available]:

- George Jones – “White Lightning” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jerry Lee Lewis – “Great Balls of Fire” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Maybe Little Baby” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jerry Lee Lewis – “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Big Bopper – “Chantilly Lace” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Rain Rain” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Treasure of Love” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Little Willie John – “All Around the World” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “If I Don’t Love You (Grits Ain’t Groceries)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Waylon Jennings – “It’s Alright” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Just One More” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Color of the Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny PayCheck – “It’s Been a Long, Long Time for Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny PayCheck – “I Guess I Had It Coming” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Mr. Fool” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny PayCheck – “Shakin’ the Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “The Last Town I Painted” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Revenooer Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Who Shot Sam” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Out of Control” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Glad to Let Her Go” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “You’re Still on My Mind” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny PayCheck – “The Window Up Above” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny PayCheck – “One Day a Week” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Aching Breaking Heart” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Tender Years” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones & Melba Montgomery – “We Must Have Been Out of Our Minds” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones & Gene Pitney – “I’ve Got Five Dollars and It’s Saturday Night” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny PayCheck – “A-11” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Walk Through This World with Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Excerpted Video

These videos were excerpted in the episode. For any number of reasons, YouTube may remove them in the future but here they are for now:

Commentary and Remaining Sources

Alright, these Liner Notes should be fun…

When I said the KKK hated what they viewed as a Roman Catholic drinking culture, that is precisely what I meant and nothing more or less. I did not say they were correct in that or any other view and I did not say that members of the KKK were any less hypocritical than nearly everyone else discussed in that segment of this episode. The various groups I referred to multiple times who supported Temperance and Prohibition for religious reasons obviously included many Roman Catholics.

There was this one little thing I found out about while researching this episode that was a pretty amazing connection between the intro and the song “White Lightning” but, from a storytelling standpoint, it just didn’t make sense to include it anywhere in the main episode. So here it is now: Pig Robbins loves going to NASCAR events. There’s an article in a 1982 issue of Illustrated Speedway News with him saying “The thunder of those engines… The smell of burning rubber on the asphalt… The cheering of the crowd, which is almost constant at Talladega because of all the passing… Well, it’s the most exciting thing I’ve ever experienced. It’s hard to describe the tingle that goes through my body. I’m not kidding. It’s almost like a powerful piece of music to me.” End quote. I just thought that was a cool thing and wanted to share it.

I expect a certain amount of people to hear the whole point of this episode as “fuck Johnny PayCheck” just as their main takeaway from the previous two episodes was “fuck Chet Atkins,” regardless of how many positive things I said and how careful I was to supply proper context. So, let’s get into it. First off, talking about a bunch of random people who decided Johnny PayCheck should get credit for something he didn’t do is in no way a criticism of Johnny PayCheck. He wasn’t one of the people who believed this. The reason nobody’s ever gonna find a quote from Johnny PayCheck saying he should get credit for the way George Jones sang is because PayCheck knew who his own influences were. A lot of folks who want this “Jones took a lot of his style from PayCheck” theory to be true are certainly gonna get pissed off by someone saying it’s actually the other way around but I don’t care. They’re wrong.

One reason I know how common this theory is among country fans is also the reason I know how easy it is for everyone who’s not a complete shithead to change their mind about it: I believed it was true for a long time. The reason I thought it was true is the same reason so many people still believe it, which is that until fairly recently the evidence seemed to back it up. Most people have never heard many of the song clips in that segment of this episode because the songs weren’t released until decades after being recorded. Many of the songs that were released still came out at least a few years after the sessions. For everyone paying attention to this stuff in real time, trying to put together a picture of what happened and when, the only thing they had to go on was the records that came out and the labels on the records didn’t include information about how long ago the sessions took place. Now that we do have comprehensive box sets that do come with that information, now that everyone reading this has had that information placed into greater context by this episode, the only way to argue PayCheck dictated George Jones’ vocal style is by ignoring all of the facts, which I would and did call ridiculously ignorant. When I researched a theory I believed to be true, I found out it was based on incomplete and inaccurate information, at which point I understood the theory was wrong and updated my beliefs. Anyone who can’t do the same thing will continue to have huge problems with this podcast.

While we’re on PayCheck, it’s worth pointing out he didn’t only play bass. Among other instruments, he could also play pedal steel guitar and he did sometimes do that as a Jones Boy and in the bands of other country artists.

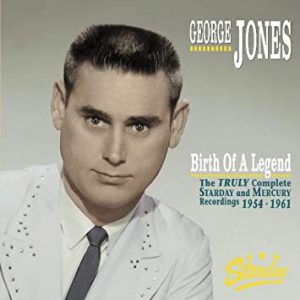

As for my sources, other than those mentioned in the episode, one of the best sources for George Jones’ time at Mercury is The Complete Starday & Mercury Recordings box set released by Bear Family Records. While all of their box sets usually come with pretty great booklets giving all kinds of information on the recordings, this box set actually comes with a hardcover book by Kevin Coffey. There are all kinds of great pictures and the whole first part of the book is sort of a chronological narrative around the recording sessions with bits of biography on George Jones or the songwriters of the material or the musicians, etc. The part that was most useful for me, though, was in the back, where they give as much data as possible on the recording sessions, when they happened, which musicians were in the room and so on.

My other main sources are all on the Season 2 Library page and I think it makes the most sense to discuss each of those sources in the Liner Notes of the episodes to which they are the most relevant. So we’ll get into those later.

The most important source for all the moonshine stuff in the intro is a documentary which I believe may be officially titled The Last One but which I first saw years ago on YouTube with a title something like This Is the Last Damn Run of Likker I’ll Ever Make (video embedded above) and which is, of course, a quote from Popcorn Sutton. (This is the first time I’ve ever had to come back and make any kind of correction on Cocaine & Rhinestones. It’s just a comment in the Liner Notes but, still, worth correcting. I don’t know if it’s due to the name change on that documentary or what but there seems to be some confusion amongst various sources. Popcorn was definitely lying about that being the last run of moonshine that he made because it was filmed several years before his last bit of trouble with the government. And the filmmaker was not involved when Hank Williams Jr. partnered with Popcorn’s widow to make legal whiskey bearing Popcorn Sutton’s name. That’s all.)

As for the rest of the history of moonshine and the Whiskey Rebellion and Prohibition, I did the same thing I had to do for all of the not-explicitly-musical history in this season, which is cast a wide net and try to land a general consensus of what is agreed upon by most historians using the most up-to-date information. As we’re seeing so often in the United States right now and for the past several years, a lot of folks want to pick one source of information for their history and that one source often has a lot more to do with what any given person would like to believe is true than any desire to find out what is true. So I didn’t pick any single source and no significant portion of anything I said was unique to one source to such a degree it would need to be named here. However, this is a pretty fascinating corner of American history, so there are a lot of books written on these topics, from serious and dense to lighter collections of trivia and factoids. Though you won’t find all of the information I gave in these few books, some I can recommend would be Bootleg by Karen Blumenthal, Moonshine by Jamie Joyce and Prohibition by Edward Behr.

Okay, meet me back here in a couple weeks if you’d like to hear some more about George Jones’ time as a Starday recording artist.