Now that we’ve established Owen Bradley as the single most important producer in the history of Nashville, let’s take it further and acknowledge he’s one of the most important figures in the history of all recorded music, even if for no other reason than assembling the first group of musicians to become known as the Nashville A-Team. Were we to erase their work from existence, every book about pop, rock or country music in the second half of the 20th century would need to be entirely rewritten. Just ask Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan, 3 out of 4 Beatles, The Everly Brothers, Patsy Cline, Ray Price, Loretta Lynn, Dolly Parton, Roy Orbison, Roger Miller, Hank Williams, Marty Robbins, etc. And those are just the people who can speak from first-hand experience. If you want to start talking about the influence of the records, well, strap in.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

In addition to The Main Library and the Season 2 Library, these books were used for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

As part of my agreement with Simon & Schuster to publish a book adaptation of Season 2, the transcripts that have been freely available for over a year will be temporarily removed from this website. Please consider ordering a copy of Cocaine & Rhinestones: A History of George Jones and Tammy Wynette through your favorite local bookstore or requesting that your local library order a copy you can check out.

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [with links to purchase or stream where available]:

- Violet Gordon Woodhouse – “Heddon of Fawsley” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Mark Andrews – “Silent Night” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jelly Roll Morton – “King Porter Stomp” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Roger Miller – “King of the Road” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tammy Wynette – “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Color of the Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Strait – “Amarillo by Morning” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Little Jimmy Dickens – “A-Sleepin’ at the Foot of the Bed” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Webb Pierce – “I Ain’t Never” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Elvis Presley – “Heartbreak Hotel” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Gene Watson – “14 Carat Mind” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dolly Parton – “Jolene” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Arthur ‘Guitar Boogie’ Smith – “Fingers on Fire” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Paul Howard & His Arkansas Cottonpickers – “Drinking All My Troubles Away” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Cowboy Copas – “Opportunity Is Knocking at Your Door” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Django Reinhardt & The Quintet of the Hot Club of France – “Manoir de mes reves” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Autry Inman – “You’ve Got to Leave Those Other Guys Alone” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Webb Pierce – “Wondering” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Eddy Arnold – “I’ve Been Thinking” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Marty Robbins – “El Paso” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Lefty Frizzell – “Saginaw Michigan” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Horton – “Honky Tonk Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Horton – “I’m a One Woman Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Horton – “The Battle of New Orleans” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Horton – “When It’s Springtime in Alaska (It’s Forty Below)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ruby Wright – “Dern Ya” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ruby Wright – “Such a Silly Notion” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Carl Smith – “Why, Why” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Hank Williams – “Move It on Over” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Moon Mullican – “Sugar Beet” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Everly Brothers – “Cathy’s Clown” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ernest Tubb – “Have You Seen My Boogie Woogie Baby?” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ernest Tubb – “The Yellow Rose of Texas” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ray Price – “Don’t Let the Stars Get in Your Eyes” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ray Price – “Much Too Young to Die” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ray Price – “Run Boy” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ray Price – “Crazy Arms” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ray Price – “I’ve Got a New Heartache” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ray Price – “My Shoes Keep Walking Back to You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Brenda Lee – “Heart in Hand” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Patsy Cline – “Walkin’ After Midnight” (re-recording) [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Webb Pierce – “Honky Tonk Song” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Hank Locklin – “Please Help Me I’m Falling” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Grady Martin – “The Fuzz” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Floyd Cramer – “Last Date”[Amazon / Apple Music]

- Skeeter Davis – “My Last Date (With You)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Conway Twitty – “(Lost Her Love) On Our Last Date” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Emmylou Harris – “(Lost His Love) On Our Last Date” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Loretta Lynn – “Success” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Four Flickers – “Long Tall Texan” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Beach Boys – “Long Tall Texan” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dale Potter – “Faded Love” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bill Monroe – “Sitting on Top of the World” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Webb Pierce – “Any Old Time” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Webb Pierce – “Teenage Boogie” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Webb Pierce – “We’ll Find a Way” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Webb Pierce – “I Think of You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Elvis Presley – “Hound Dog” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Elvis Presley – “I Want You, I Need You, I Love You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Elvis Presley – “Don’t Be Cruel” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Brenda Lee – “Sweet Nothin’s” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Carl Butler – “Grief in My Heart” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ann Margret – “I Just Don’t Understand” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Beatles – “I Just Don’t Understand” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Roy Orbison – “Candy Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobby Vinton – “Blue Velvet” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobby Vinton – “What Color Is a Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Merle Haggard – “Mama Tried” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bob Dylan – “Outlaw Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bob Dylan – “Positively 4th Street” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bob Dylan – “Desolation Row” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bob Dylan – “To Ramona” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bob Dylan – “Most Likely You Go Your Way and I’ll Go Mine” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bob Dylan – “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Lovin’ Spoonful – “Nashville Cats” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dolly Parton – “It’s Sure Gonna Hurt” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Chet Atkins – “Mr. Sandman” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Pete Drake – “Forever” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Little Dippers – “Forever” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Roger Miller – “Lock Stock & Teardrops” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Roy Drusky – “Anymore” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Harrison – “All Things Must Pass” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Warner Mack – “Bridge Washed Out” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny PayCheck – “Motel Time Again” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Byrds – “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Alan Jackson – “Remember When” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ween – “Pretty Girl” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Excerpted Video

These videos were excerpted in the episode. For any number of reasons, YouTube may remove them in the future but here they are for now:

Commentary and Remaining Sources

Okay, these Liner Notes could go long because the type of people who care a lot about stuff like session musicians also tend to be the type of people who want to find any pedantic way in the world to have a problem and argue with something another person said about music, even if they 100% agree with the point and only want to argue about the way it was said. So let me start by reiterating what I said in the last episode’s Liner Notes, which is that you listening to my voice say things does not mean the things you’re hearing are my own personal opinions. I don’t intend to repeat this in the Liner Notes of every episode but the rest of this season is going to get extremely messy for everyone who can’t differentiate between hearing me say something and hearing me preach or endorse something. I do understand how convenient it is to dismiss something that doesn’t gel with your own ideas by brushing it off as another person’s opinion which you can just choose to disagree with. But I didn’t start this podcast as an attempt to force my personal opinions to become history. For an example (which really shouldn’t matter as much as I’m sure it does to certain people), I love Elvis Presley’s recording of “Hound Dog.” I think it’s fucking great and that’s something I could talk about for ten minutes. But Gordon Stoker explained on multiple occasions how terrible he thought The Jordanaires sound on that song. I’m not going to have sidebar arguments in the middle of an episode every time my personal opinion doesn’t align with the musician I’m talking about. What I’m going to do, to the best of my ability, is try telling you the story the way you’d have heard it from the people in the story. And the reason why I’m going to prioritize that over any other single aspect of this entire project is I don’t want those people to haunt me in my dreams.

In the interest of trying to preempt as many nitpicky emails as possible, I’ve got to run through quite a few things right now…

There’s always going to be stuff in this podcast that musicians (and especially non-country musicians) will identify as technically wrong. There are a few reasons for that but the main one is I’m trying to tell stories to people who don’t know and will never care about things like the difference between a baritone guitar and a six-string bass. Basically anytime you hear me refer to a baritone guitar at any point in the existence of Cocaine & Rhinestones, what I am technically referring to is a six-string bass guitar. The reason I call it a baritone guitar is because that’s what country musicians called it at a time, even after having it pointed out to them that it’s a six string bass. When you read and listen to members of the Nashville A-Team tell stories, they’ll sometimes even follow up a reference to baritone guitar by clarifying that it’s really a six string bass… before going right back to calling it a baritone guitar because that’s what they’ve always done. There is even an article in Premier Guitar magazine talking about this exact thing, how the phrase “baritone guitar” was in colloquial usage years before that type of instrument was even being mass produced. I would guess the reason A-Team musicians called six-string bass “baritone” guitar is because they treated it more like a guitar than a bass in songs like “The Race Is On,” “Six Days on the Road,” all those Johnny Horton songs and many, many other country hits coming out of Nashville and California in the 1960s. So, yeah, it’s a bass but the musicians called it a baritone guitar and I’m gonna keep calling it a baritone guitar. I’m sorry to the handful of people 50 people this will annoy but it’s not worth derailing the story everyone else is happily enjoying. Same thing goes with the definition of “syncopation” given in this episode. I know you went to music college and it drives you nuts that all these hillbillies and rednecks down in Nashville were making wildly influential hit records without knowing how to read sheet music or properly define the terms from classical music theory that they used in the studio every day. But that’s kind of the point of this whole episode. In every episode of this podcast, there are so, so many digressions I could take off of nearly every sentence. Yes, the way I tell stories does include a lot of tangents but none of them are there just because I can put them there or because I feel the need to explain every little detail. The only reason you’re ever hearing me say anything at all is because I believe it makes the story better to hear what I’m saying. So, yes, I will take the time to briefly explain the core concepts of music theory in order to give everyone an idea of how revelatory the Nashville Number System was because that does matter to your understanding of Music Row’s place in the history of music around the world. And taking the time for that tangent means I’m probably not going to make time to clarify that there are some people in Vienna or Berkeley who would like you to know these A-Team players were using a few words incorrectly. I’m gonna keep calling it a baritone guitar and getting mad at me for it makes about as much sense as getting mad at me for calling a violin a fiddle.

I know someone wants to tell me both harpsichords and pipe organs get louder when you play more notes at the same time because the volume is accumulative. Exactly what I said is each individual tone sounds at the same volume and that is true. The point is if you press an individual piano key with much more force, the tone sounds at a much louder volume and that’s not what happens on pipe organ or harpsichord. I should also say: because of how quickly the pianoforte evolved, we now refer to the original design as fortepiano (or “loud soft”) in order to distinguish it from modern piano.

The intro of this episode wasn’t me saying all of those instrumental parts were dictated to all of those musicians from a piano. It was me saying I know the invention of the piano created the possibility for that to occur, regardless of whether or not it’s what happened with any single one of those parts of those songs.

I said James Burton “copied” Chip Young’s guitar part to dobro and, looking back at that, a better word to use would have been “adapted” because the “What Color Is a Man” part is obviously based around a series of pull-offs that would be virtually impossible to straight-up replicate on dobro. However, the point stands, which is that James Burton was unquestionably “quoting” Chip Young on “Mama Tried.”

I said Hank Williams didn’t put a drummer in his band, which is absolutely correct, but I’m sure to get several emails about it if I don’t point out Hank did have WSM staff drummer Farris Coursey play a brushed snare on the “Moanin’ the Blues” session and Farris is who played what is essentially special FX drums on “Kaw-Liga”

If you listen to the whole song there are technically four snare hits in Ray Price’s “Much Too Young to Die” because the drummer mistakenly hits his snare one time when Ray starts in on the same melody in the first verse. I didn’t count that one because it was obviously an accident and not supposed to be there.

This one is really important. There are quite a few Nashville studio musicians whose names you didn’t hear me say in this or the last episode. This should not be taken as a statement on whether or not those players belong on “official” lists of A-Team members and I would love it if everyone could refrain from asking me which people do and don’t belong on the A-Team. As I said in this episode, the term gets a lot more loose after Owen Bradley sells 804 16th Ave and leaves Music Row. I do think all of the first-call musicians working sessions for all the major labels in town at that time should be considered A-Team players, however I do not have access to any comprehensive resource specifying which players those are. For instance, not counting members of vocal groups, rhythm guitarist Velma Smith is the only woman I know of who regularly played in Nashville sessions but I honestly do not know if she was a first-call player or not. In every resource I use to check the credits of musicians, she’s only listed on a handful of albums. While those lists are certainly incomplete, I can’t speak with any certainty as to how many sessions she did play. Comparatively, I know for a fact Ray Edenton was a first-call player because he worked over 10,000 sessions in his career.

Velma Smith being the only woman who it’s even possible may have been considered an A-Team instrumentalist and Anita Kerr’s frustrations with the Nashville studio system in general raise the recurring issue of Music Row being a boy’s club. No big surprise there but because that was the situation I did want to draw attention to a subtly implied theme of these past two episodes, which is how far Owen Bradley went out of his way to work with and support many women artists during an era when women artists were commonly viewed by the industry as a risky investment. I did not follow this thread in a direct way because it felt like something that would be more appropriate and more interesting to explore during a future season from the perspective of an individual artist who worked with Owen, drawing on the understanding we all now have of him from these episodes. Because I know this will play a huge part in something I have planned for the future of this podcast, I didn’t cover it here in order to avoid retreading the same ground later.

And one last thing for the “gotcha” crowd, I am aware of how many popular songs are founded on pentatonic scales rather than diatonic scales. I didn’t talk about that for the same reason I didn’t talk about minor scales, didn’t mention the F# in the key of G, didn’t talk about modes or borrowing chords from other keys or any other pieces of harmonic theory, which is all those things are too complicated to unpack during what I was doing in that part of the episode. What I said is true: popular music in America exists atop the foundation of diatonic scales. As any student of harmonic theory knows, altering those scales can be as deep and complex as you want to go but the short intro given in this episode is enough for any self-taught musician to start taking everything apart and putting it back together for themselves and that’s what I hope to inspire. For all the musicians who do fall into that category, the next thing I’d suggest looking at is how triad chords are formed by a first, third and fifth. So if you’re looking at your piece of paper with the C scale on it, what makes a C chord a C chord is that all the notes in any given C chord shape are C, E or G, the 1, 3 and 5 on your paper. If you go to the 4 chord in the key of C, which is F, what makes that chord an F is its root note (or 1) being an F and counting forward to the F’s 3, which is A, and forward to the F’s 5, which is C. Do make sure to look up which flats and sharps are in each key before you get way into this but that’s enough to real deep for a long time.

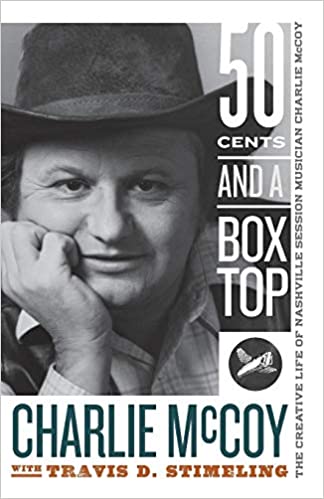

As far as sources for this episode go, it’s the same thing as the last one. Nearly everything you heard me say is a product of researching in the archives at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, as well as the reference materials on The Library page. The only other book I used on this episode was the already-mentioned autobiography of Charlie McCoy, which I can recommend to anyone interested in further reading.

And that’s all for Season 2’s introduction. Next week, we get down to all kinds of business with “White Lightning.”