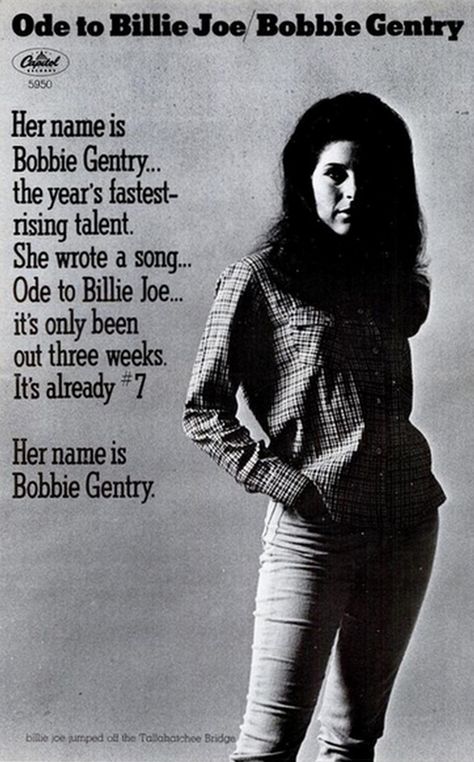

In 1967, Bobbie Gentry’s recording of a song she wrote, called “Ode to Billie Joe,” directly influenced the future of every major musical genre in America. In the early ’80s, she disappeared.

What happened in the decade between?

Why did Bobbie Gentry vanish?

Who was she, even?

Since we can’t ask Bobbie for answers, these are mysteries we either have to learn to live with or try to solve for ourselves.

This episode of Cocaine & Rhinestones examines every little thing we know about Bobbie Gentry, her life and her music. Today’s story takes us from the cotton lands of Mississippi to the music scene of Los Angeles, from a legendary recording studio in Muscle Shoals to the white hot lights of Sin City. We’ll explore major label music marketing, the concept of celebrity personas, the state of American pop/rock in the ’60s, and just what exactly the hell a MacGuffin is.

People you’ll hear about in this episode: Glen Campbell, Elvis Presley, Jim Stafford, Nick Lowe, Kanye West, Eminem, Drake, Lauryn Hill, Snoop, A Tribe Called Quest, Jody Reynolds, Rick Hall, Lou Donaldson, Sheryl Crow, kd lang, Lucinda Williams, Alfred Hitchcock, Barry White, Bobby Womack, Burt Bacharach and, believe it or not, more.

Also, you may not like what you hear if you’re a fan of Jim Ford.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

In addition to The Library, these books were used for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

It’s Not Your Brain

Why would anyone want to be famous?

Or, let’s begin with a simpler question: why does society want celebrities?

That’s easy.

If you’ve ever enjoyed a work of fiction, like a book or a movie, then you know the answer. A celebrity is a living character in a story we’re telling ourselves and each other, a touchstone for a personality type. The fact that it’s a real person, out there, acting on their own free will, only makes the story better.

Sometimes we imagine a celebrity as the best version of ourselves – achieving the goals in the world that we would achieve if we had that body or those opportunities, answering questions and reacting to circumstances the way we like to think we would. We compliment others by telling them they resemble a movie star or sound like a famous singer. Everyone can see how successful that person is and, “You. You’ve got a piece of that in yourself that I can see.” And we’ve all met a person who’s gone out of their way to let us know they frequently receive this type of compliment: “People tell me I look like Ryan Gosling.” “My friends say I sing like Adele.”

Sometimes we imagine a celebrity as the best version of a best friend or the best version of a lover – someone we really understand; someone who would really get us, give us a sense of fulfillment, in one way or another. We listen to the hosts of our favorite podcasts joke with each other and we laugh as if we’re sitting at the table with them, like we’re a part of that conversation. Couples half-jokingly give each other a hall pass for a celebrity they’d be allowed to sleep with if the opportunity somehow presented itself.

Sometimes we imagine a celebrity as an enemy or a hero, a face to fight against or alongside on the social and political battlefield. Kanye West refers to himself as a genius and there’s your uncle ranting about it on Facebook. It gives you a thrill to see Nicki Minaj paying off a fan’s student loan.

My definition of “celebrity” isn’t exclusive to the faces on magazine covers in the checkout lane or the A List examples I’ve been using for convenience sake. Celebrities are people you do not personally know, whose actions or reactions do not represent a direct threat or direct support to your survival, yet you maintain an emotional investment. Kanye West calling himself a genius isn’t going to kill anyone or put anyone in the hospital, so why does your uncle care?

Because he needs an enemy.

Nicki Minaj didn’t pay off your student loan, so why do you care?

Because that’s what you would do. That’s what you’d want your best friend to do if they got rich and famous. Because you need a hero.

Okay. But why on Earth would any individual want to cast themselves in these roles for millions of people? Or even a thousand people? Your every act holding the potential to destroy the fantasy-version-of-you that is so important to random strangers. There becomes an obligation to be the person everyone has decided you are. Doesn’t that sound awful to you?

On top of that, being famous literally shaves years off your life. Analysis of 1,000 obituaries in the New York Times from 2009 to 2011 showed an average age of death of 77 years old for famous people. That’s compared to averages of 81 for academics and 83 for business (and, even military) personnel. Another study of nearly 1,500 musicians who became famous between 1956 and 2006 showed an average age of death of 45 years old for North American musicians and 39 for those from Europe.

Fame kills with stress, substance abuse and psycho stalkers.

Why would anyone want that?

It’s Just the Flame

We often assume the desire for fame is a desire for wealth. Perhaps even most people chasing after fame believe they want it so they can be rich. But every single practical reason you might come up with for wanting to be rich, having money without fame can get you those things. VIP status can be purchased across the board.

You don’t have to become a celebrity to become a doctor or lawyer or software developer. Those are three of the highest paying jobs in existence right now. Maybe not everyone has the resources to become a doctor or lawyer but you can learn to code online for free right now at a library. Between finding a high paying job as a coder and achieving a level of fame that would bring you riches, your odds as a coder are surely much better. So go be a millionaire.

Except wealth is only the second most common reason for wanting to be a celebrity.

The third most common reason people seek fame is to make the world a better place by “being a good role model” and “supporting causes that matter to [you].” Again, you can do those things and, arguably much more effectively just by becoming rich. The more attention called to every minute detail of your life and the less perfect you are, the greater the potential for you to negatively impact your chosen social cause. It’s only a matter of time until you say or do the wrong thing and the opposition holds you up as a bad example of your side of the argument.

So what’s the number one reason people want to be famous?

Because you want to be famous.

That’s it. Full stop. Fame for the sake of itself. You want to be on the cover of a magazine. You want recognition in public. You want to walk into a room and feel the energy change because of your presence. Taken to an extreme, this is a desire for a place in history. But why, though? What is that?

Modern psychology thinks it has answers: narcissism, vanity, egomania…

Various studies have uncovered the relationship between intrinsic or extrinsic goals and mental health. Humans with a focus on achieving intrinsic goals – meaningful relationships with other people, a helpful role in their community, personal growth and self-development – these goals are associated with stronger mental health, general happiness and satisfaction in life. Humans with a focus on extrinsic goals – a desire to be (or at least be thought of as) rich and/or famous, a need to be recognized, a focus on material wealth – these goals have been found to be associated with dissatisfaction and depression.

This isn’t a scientific fact or a law of physics or anything. Behavioral studies like this can only show associations and there will always be unanswered questions. For one thing, how many millionaires and movie stars were questioned in these studies?

I don’t know.

Poor people who want to be rich more than anything and gas station employees who want to be famous more than anything – clearly not gonna be that thrilled with their lives. It’s quite possible the only thing these studies show is that people who set realistic goals for themselves have an easier time achieving them and are, therefore, happier. It’s a lot more difficult to amass financial wealth or become a movie star than it is to make friends and try to be a good person to the people in your life. Most major religious and philosophical ideologies tell us the same basic thing when it comes to chasing after money: even if you get it you won’t be happy because that’s not what’s keeping you from being happy. It seems to check out. Everyone’s heard the stories of how bad things often turn out for those lucky few who win the lottery…

But is it really so easy to lump fame in with fortune and say it’s all so superficial? What about the idea of being destined for greatness? What about the concept of glory?

We internalize those notions from Disney cartoons before learning basic arithmetic. Of course, modern psychology suggests whether or not we become adults with mostly internal or mostly external goals is largely determined by the circumstances of our childhood – what kind of parents we had, how valued we felt, how rich or poor we were.

For example, let’s say there’s a little girl named Roberta Streeter, born in Mississippi in 1942

Roberta

It’s a classic poor country girl scenario.

Roberta’s parents were only able to keep it together for the first year of her life. After they split, Roberta lived with her father’s parents on the family farm outside Woodland, MS. The current population of Woodland is somewhere around 125 people. The farm didn’t have electricity and Roberta didn’t have many toys. But transistor radios run on battery and Roberta was able to pick up radio waves from New Orleans. When her obsession with music became evident, her grandparents traded one of their cows for a used piano. Roberta taught herself how to play it.

When it came time for Roberta to enter 1st grade, she went to live with her father in Greenwood, MS. Today, Greenwood’s population is somewhere around 14,500 people. Still very much a farming area, the official nickname is The Cotton Capital of the World. It probably seemed like New York City to little Roberta. She had electricity in her new home – big step up.

It was sometime around here when she wrote her first song, called “My Dog Sergeant Is a Good Dog.” Perhaps not on track to be the next Mozart but she was listening to more jazz and blues music than anything else. Simple lyrics, straight to the point – that’s the style of these genres. For instance, I’ve heard Billie Holiday sing songs with less complicated titles than “My Dog Sergeant Is a Good Dog.” The important thing is to notice how, even at such a young age, her impulse was to create rather than simply imitate.

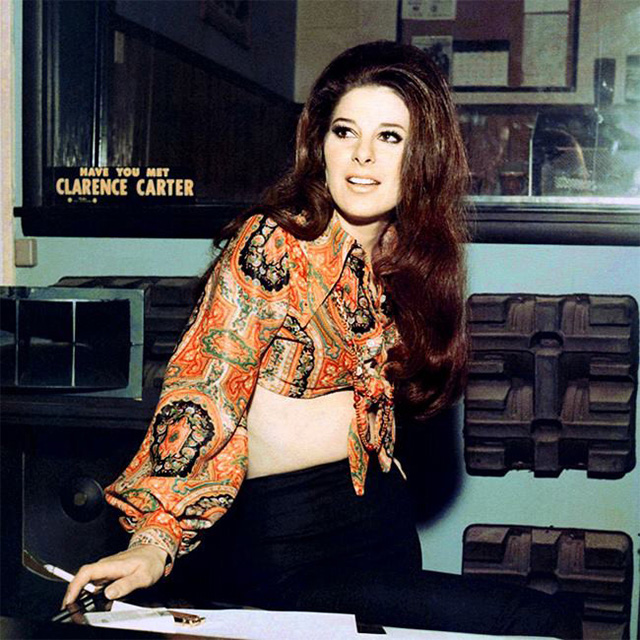

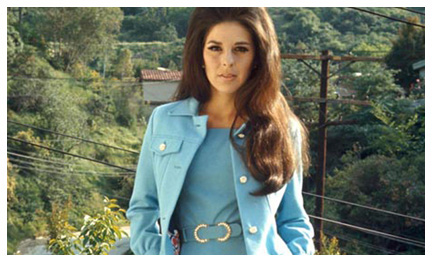

We don’t have much more information about Roberta’s childhood in Mississippi, even though Capitol records would lean heavily on these years when creating her public persona: the poor country girl.

It is a true story but it’s only half of the true story.

Bobbie

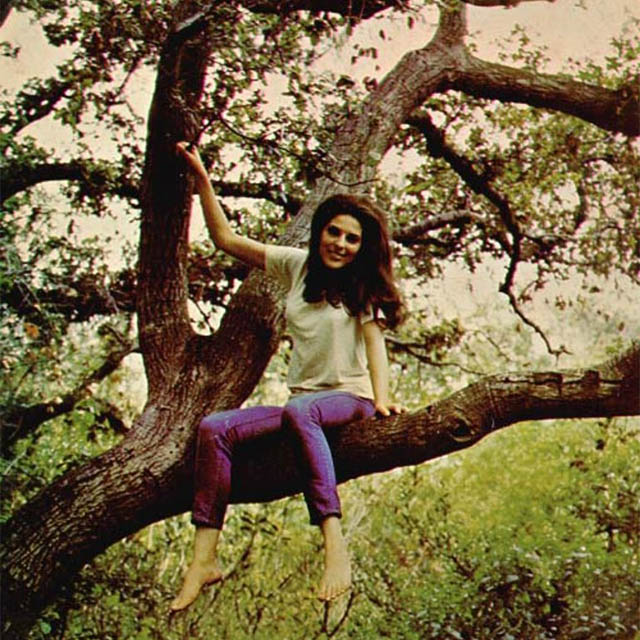

Roberta’s mother’s name was Ruby. Ruby was a looker and seems to have had a real talent for marrying up. In 1957, Ruby’s latest marriage finds her living in Southern California. Thirteen-year-old Roberta moves in with her mother – first in Arcadia and then, a couple years later, Palm Springs. They belong to a country club. Roberta learns to play golf and ride horses, does some modeling and adds art studies to her ongoing interest in music.

Roberta may have been called Bobbie by her family even as far back as the farm. Here, in Palm Springs, Bobbie Streeter gets left in the past. First, it’s Bobbie Meyers – her stepfather’s last name. But when Bobbie sees the movie Ruby Gentry, that’s when Bobbie Gentry is born. The movie is about a poor country girl who marries a rich man even though she’s in love with a not-rich farm boy. The rich husband’s friends do not accept her into high society. Therefore (Spoiler Alert), when the rich guy dies in a boating accident and she inherits his money, she uses the fortune to get revenge on all the upper class types who were mean to her for once having been poor.

There’s more to it than that but that’s the part a half-country/half-country club girl would get excited about. With the main character sharing a first name (and maybe a little more than that) with Bobbie’s mother, Bobbie takes the last name “Gentry” for herself. This is around the time she graduates high school.

1960, at the age of seventeen: Bobbie Gentry moves to Los Angeles to work as a secretary and chase her dreams on the side. Those dreams at this time are to become a songwriter – nothing too ambitious, no deep hunger for the spotlight. She simply feels she’s got something to say, something people would want to hear if they heard it on the radio.

But performing comes easy to Bobbie Gentry, even back when it was Bobbie Meyers, playing in a little mother-daughter act around the country clubs of Palm Springs, just for fun. So when Bobbie arrives in L.A. with not much in the way of connections, one way to make those connections is by taking whatever solo gigs she can get in cocktail lounges and nightclubs. Besides, it’s extra money, it is fun and the thing about Los Angeles is you never know who’s gonna be in any given room on any given night.

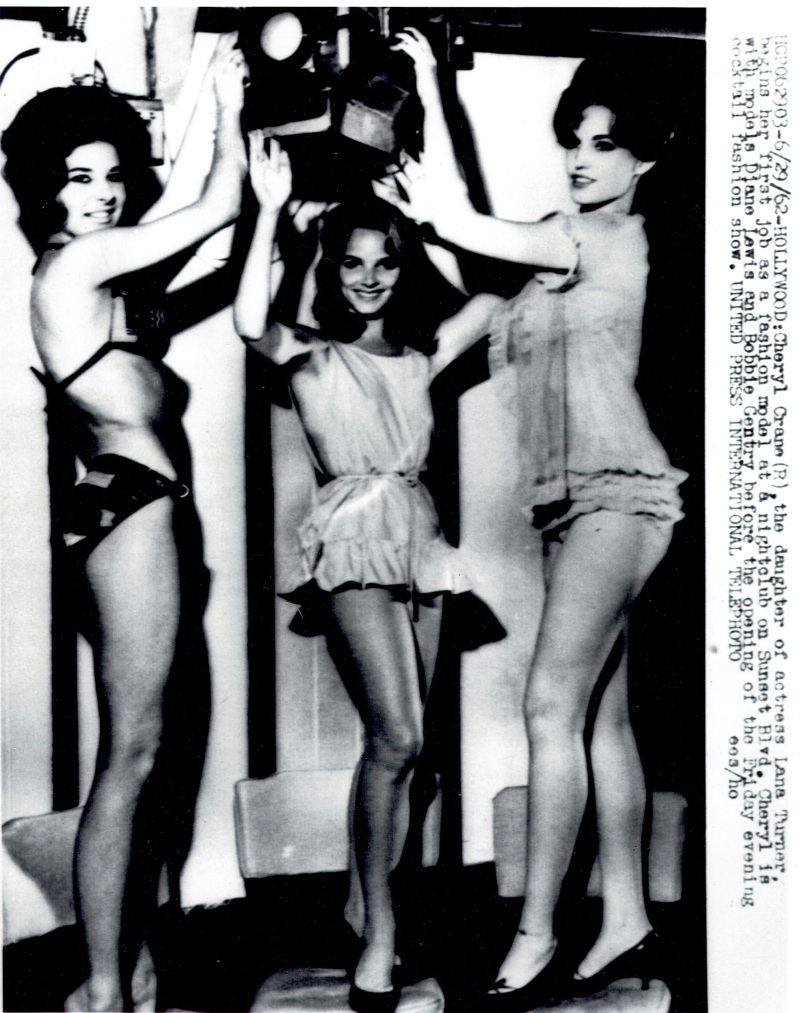

Within a couple years, Bobbie’s dancing in Johnny Ukulele’s Las Vegas act. Johnny Ukulele’s father was literally a Hawaiian prince and Johnny had been playing Hawaiian music in the United States since 1916. Bobbie’s brunette hair is all it takes for American audiences to think she looks the part but she takes her role quite seriously, even studying traditional Hula dancing.

Back in L.A., she puts together her own Hawaiian-themed group to play the Southern California, Las Vegas & Lake Tahoe showroom circuit. She runs the whole act, from hiring musicians to finding a booking agent, outlining the set, even designing and sewing the costumes herself. She’s still touring with this act when her single “Ode to Billie Joe” comes out on Capitol Records and changes her entire world.

But you’ll want to hear how that happened.

There in the Breakers

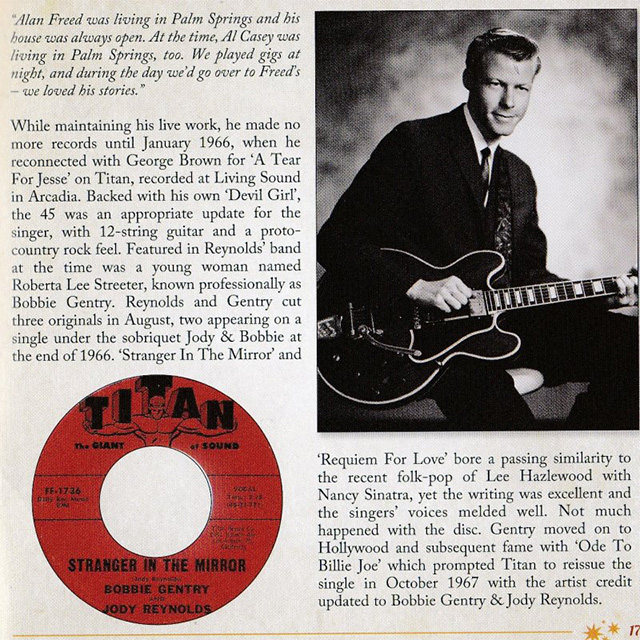

Hanging out in a club one night, Bobbie liked the band. She went up and asked if she could sing a song. They said “yeah” and the leader of the band liked what he heard so much that he asked Bobbie to sing on a record he was doing soon. This guy is Jody Reynolds, whose name you may recognize from his 1958 Top 5 Pop hit, “Endless Sleep.” If you’ve never heard his version, you probably heard a cover from The Judds or Marty Stuart or possibly Hank Williams, Jr.

Jody never had another big hit, which is why, here in the early ’60s, he’s playing some random nightclub. But he gave Bobbie her first experience in a recording studio, singing on “Requiem for Love” and the b-side “Stranger in the Mirror.” She even got to share top billing. The label on the record listed the act as “Jody & Bobbie.”

Now, there’s a lot of confusion about when this single was released. I’ve seen every year from 1963 to 1966. I’m inclined to believe it’s much closer to 1966. If this came out in 1963 then, two years later, Jody & Bobbie could have sued the entire rock music scene of San Francisco for plagiarism. In other words, nothing sounded like this in 1963, specifically the sitar-influenced lead guitar in a rock song. Nobody would have heard that until the Yardbirds’ “Heart Full of Soul” in the summer of ’65 and, by 1966, everything sounded like that. Also, Jody Reynolds never did another single that sounded like this. So either he and Bobbie Gentry invented psychedelic rock in 1963, walked away from it and never took credit for it when it blew up two years later… or they jumped on a fad, which seems more likely.

The only reason it’s worth wondering how close to 1966 “Requiem for Love” came out is because it’s the only indicator of momentum we have for Bobbie before her 1967 debut single as a solo artist knocked The Beatles out of the #1 position on the pop charts and stayed there for four weeks.

This is where we have to start talking about a guy named Bobby Paris. (Don’t get confused between Bobby the boy and Bobbie the girl.) Paris had a little hit in 1966 with a song called “Night Owl” that sounds a lot like a Tom Jones single [“It’s Not Unusual”] from the year before… “Night Owl” got Paris signed to Capitol Records.

Paris saw Bobbie playing in a little bar and struck up a conversation. He needed a rhythm guitar player for some recording sessions, so he and Bobbie made a deal. She’d play guitar on some songs for him. In return, he would use some of his studio time to record a demo tape of Bobbie doing her original songs and help her get that tape to Capitol Records. They also agreed to give each other 1% of each other’s record sales, in case either one of them helped the other one make a huge hit. The demo was made and it did end up at Capitol Records but it’s not exactly clear how big of a role Paris played in that. Although, he would take Bobbie to court later to get that 1%.

M-I-S-S-I-S-S-I-P-P-I

Bobbie’s publisher, a guy named Larry Shayne, is who sent her demo to Capitol. Remember, all Bobbie Gentry really wants is to be a songwriter. She’s got a publishing deal and her songs are in a pile at a major label, so things are starting to look pretty great. When Capitol Records likes her song “Mississippi Delta” that’s even better. Except, they don’t only like the song. They like the recording.

Why find another artist, book studio time and pay musicians to try to recreate a song from scratch when you’ve already got a good take on it?

This is how Bobbie Gentry ends up with an artist contract at Capitol Records. The Gentry/Paris demo of “Mississippi Delta,” with no overdubs of any kind, is what gets released on Bobbie’s first Capitol single. In keeping with the Mississippi vibe, another of Bobbie’s songs, “Ode to Billie Joe,” is chosen as the B-side.

In the last 50 years, it’s been analyzed to death, certain aspects of it taken out of context, magnified and blown way out of proportion. You should give yourself the chance to hear it without expectations before letting me or anyone else dissect it for you.

Okay.

The demo recording of “Mississippi Delta” is packed with a full band and horns. It would have been impossible to neatly add or remove any other sound. That’s why the demo was released as-is. But the Gentry/Paris demo of “Ode to Billie Joe” is just Bobbie singing and playing guitar. When Larry Shayne sold the recording to Capitol for $10,000, his only condition was they not try to add a rhythm section to the song. Just from listening to it, I’m guessing Bobbie recorded the demo without using a metronome or a click track. Trying to add drums to that would have been a nightmare. It would also exaggerate Bobbie’s imperfect rhythm, potentially ruining the song. On the other hand, Capitol felt releasing a “girl with her guitar” b-side on a southern soul a-side would be downright embarrassing. They brought in the composer and arranger Jimmie Haskell to cover it with strings.

Jimmie Haskell, Ricky Nelson and Bob Luman

Haskell had already done the strings for some Ricky Nelson hits, score work on several Western films and he’s also the guy who did the theme song for The Hollywood Squares game show. You can’t say any one aspect of “Ode to Billie Joe” is what makes the song or made it a hit but what Jimmie Haskell did with the strings is practically a miracle.

First, “cover it with strings” was the only direction given to him, at all. He listened to the song a few times, decided the lyrics were telling a story as good as any movie he’d seen and arranged the strings as he would have done for a film. You can tell it isn’t going to be a normal song right away from those wheezing violins on the intro.

The other thing is, Haskell was working with an unusual crew of four violins and two cellos. Normally, it would be four violins, one cello and one viola. Haskell had one of the cellists pluck their notes, which is what sounds like a bass part riding Bobbie’s guitar through the whole song, while the rest of the strings weave in and out in response to the unfolding drama. This cinematic approach is most evident near the end, when the strings go up with the narrator going up on Choctaw Ridge to pick flowers and the strings going down when the narrator throws the flowers down off the bridge.

By the time Haskell gets done with the song, Capitol Records has a problem. It’s too good for the b-side of a record.

The staff producer assigned to work with Bobbie is a brand new hire named Kelly Gordon. At the next A&R meeting, Kelly submits both “Mississippi Delta” and “Ode to Billie Joe” for consideration as Bobbie Gentry’s first a-side. Bobbie’s original demo of “Ode to Billie Joe” was seven minutes long. Kelly Gordon had to chop it down to four minutes and fifteen seconds just so it would fit on one side of a 45rpm 7-inch but that was still a full minute and fifteen seconds longer than any record company wanted a single to be. DJs were more likely to play shorter singles to pack more songs in between commercial breaks. As a result, labels had a tendency to think of three minutes as the limit for any song with hit potential. Still, there was something about this song…

The suits at that meeting rightly chose “Ode to Billie Joe” for the a-side.

“Mississippi Delta” was moved to the b-side and, from there, everything got real crazy, real fast.

Nothin’ Ever Comes to No Good

The single was released in July of 1967. By the end of August, it was the #1 song in America. It would eventually rise to the Top 20 on country charts but this is a pop song. Bobbie Gentry was never a country artist and I’m not doing that whole “authenticity” thing. I don’t believe she ever set out to make country music.

Was her music Southern?

Absolutely, yes.

But so was Gone with the Wind. So was everything that came out of Stax Records in Memphis. Probably the quickest way for you to understand what I mean would be to go listen to Bobbie doing Doug Kershaw’s classic “Louisiana Man.” I’ll wait.

So, we’re all on the same page here, right? Not country music.

Then why am I talking about Bobbie Gentry on a podcast about country music?

Okay.

Like other not-country things, such as Hawaiian steel guitars, ’80s hair metal and pop music in general, Bobbie’s music had a huge impact on country music. We have to talk about her for context before we can even begin to talk about “Harper Valley PTA,” which I’m going to do a few episodes after this one. [I did it.]

Sheryl Crow and kd lang have both hired Jimmie Haskell when they wanted that “Bobbie Gentry” sound. Lucinda Williams cites Bobbie as one of her strongest early influences. But Bobbie also influenced basically every other genre of music.

“Ode to Billie Joe” won a Grammy award for Jimmie Haskell and three Grammy awards for Bobbie Gentry.

Lou Donaldson’s jazz cover of the song has one of the most sampled drum breaks in hip-hop history. It’s on nearly 200 songs, including Kanye West’s “Jesus Walks,” A Tribe Called Quest’s “Clap Your Hands” and other songs you’ve heard by everyone from Lauryn Hill to Drake to Eminem to Snoop. And that’s just music.

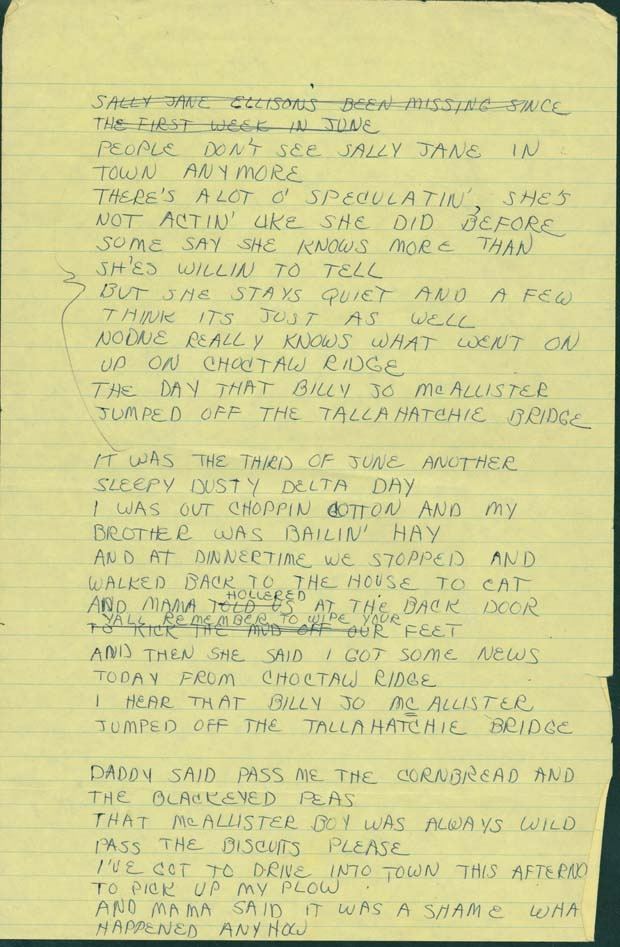

“Ode to Billie Joe” was a revelation for many people’s understanding of what could be accomplished in narrative fiction. Bobbie’s handwritten lyrics to the song are in the University of Mississippi Archives next to works by other Mississippi authors like William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams. If pop music can be considered high art, and I believe that it can, then that’s what this is.

And, for anyone who still hasn’t heard it, who ignored my earlier suggestion – this is your last chance to go and listen before I really get into it.

Alright.

Some News This Morning

The reason “Ode to Billie Joe” is respected as literature is because it tells a story as good as any short story by any other author you’d like to name. The music writer Greil Marcus was driving somewhere the first time he heard the song on the radio and he became so focused on it that he crashed into the car ahead of him in traffic.

It’s narrated by a female character who does not tell us her name. In fact, four of the five verses in the song take place around her family dinner table but we’re not told the names of any of those people, either – father, mother, brother – all nameless. Every character in the song she isn’t related to has a name.

The first name we hear is Billie Joe MacAllister and that’s because Billie Joe has jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge. We’re never explicitly told that Billie Joe died from jumping off the bridge but it’s safe to assume he did based on the response from our narrator’s family. Or, rather, on how she seems to expect a certain response where there isn’t one. Her mother eventually asks why she hasn’t eaten anything but it’s more about how long the mother spent cooking the meal than it is about why the daughter’s leaving it untouched.

The second name we get is Tom. That’s who the narrator’s brother remembers hanging out with when they and Billie Joe MacAllister put a frog down the back of the narrator’s dress at a movie theater.

Third name, Brother Taylor. He’s the local preacher who came by earlier in the day. He’s probably the source of the news of Billie Joe’s death and he apparently mentioned that he’d recently seen a girl who looked a lot like our narrator up on the Tallahatchie Bridge with Billie Joe. They were throwing something off that bridge.

The last name we get is Becky Thompson. It’s a year after the dinner table scene from the previous four verses. The narrator’s brother has married Becky and moved to Tupelo. The narrator’s father caught a virus and died in the last year. Her mother is devastated by the loss. These days, our narrator spends a lot of time picking flowers and throwing them into the water off the Tallahatchie Bridge.

In that quick recap, I rolled right through something that has driven people out of their minds for half a century. Some of you probably didn’t even notice. By all accounts, it was never meant to be such a big deal but listeners became obsessed with figuring out what it was that Bille Joe MacAllister and this girl had been seen throwing off that bridge.

Theories run the spectrum, from plausible to ridiculous, but, before I get into it, here’s the one and only correct answer, straight from Bobbie Gentry herself, repeated on multiple occasions: it doesn’t matter, at all, what was thrown off the bridge.

What’s It?

It’s called a MacGuffin and it’s pretty much always been a thing in storytelling.

A screenwriter who often worked with Alfred Hitchcock came up with a word for it and that’s what we’ve called it since the 1930s. Probably the most well known example of a MacGuffin from modern times would be the briefcase in Pulp Fiction. The plot of the entire movie centers around that briefcase. We never find out what’s in it and it doesn’t matter because the movie’s great. That’s what a MacGuffin is. It’s a random little anything used by a storyteller to move a plot forward. Other examples from movies would be The Maltese Falcon in The Maltese Falcon or the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Sometimes you find out more about the MacGuffin. Sometimes not.

The thing about the MacGuffin in “Ode to Billie Joe” is that it’s so subtle you could listen to the song 50 times and never notice that it’s there. Except radio DJs, music writers, people like me and pretty much the entire media grabbed onto it in July of 1967 and never let go.

Anyone can use a MacGuffin. There’s nothing special about it. It may be what generated so much of the original hype but this song isn’t still held in such high critical regard because it made us all wonder what was thrown off a bridge.

In her own words, as told to the interviewer Fred Bronson:

The song is sort of a study in unconscious cruelty. But everybody seems more concerned with what was thrown off the bridge than they are with the thoughtlessness of the people expressed in the song. What was thrown off the bridge really isn’t that important. Everybody has a different guess about what was thrown off the bridge – flowers, a ring, even a baby. Anyone who hears the song can think what they want but the real message of the song, if there must be a message, revolves around the nonchalant way the family talks about the suicide. They sit there eating their peas and apple pie and talking without even realizing that Billie Joe’s girlfriend is sitting at the table. – Bobbie Gentry

I think what she’s saying there is that it wouldn’t matter if you did know what was thrown off the bridge because you still wouldn’t be able to connect with this girl’s trauma. Her own family can’t connect to it and you don’t even know this girl’s name.

It’s about how nobody can ever truly feel anyone else’s pain and most of the time they can’t even be bothered to try.

Same thing with Billie Joe’s girlfriend. The loss of Billie Joe MacAllister is so devastating for her that it eclipses the grief you’d expect her to have for her own father’s much more recent passing. Instead of being there for her now-traumatized mother, she’s out picking flowers and throwing them off a bridge.

These are complex themes for major label pop music of any era. The fact that a 25-year-old kid was able to present this to the world in such a neat package is impressive. Some people might say it’s a little too good to be true. Those people believe Bobbie Gentry did not write this song…

Jim Ford

Nick Lowe, whose music I love and respect, went on NPR’s Fresh Air to tell Terry Gross how Jim Ford claimed to have written “Ode to Billie Joe.” It’s my understanding that Nick is inclined to believe Jim because, well, you can read it for yourself…

He was an extraordinary man. He wrote lots of songs for Bobby Womack and he also claimed to have written “Ode to Billie Joe.” You know the song? And, really, in the light of what Bobbie Gentry has done… I mean, it’s such an extraordinary song and so typical of a Jim Ford song and Bobbie Gentry’s never really done anything that’s remotely like that. I think that, you know, it might be possible. – Nick Lowe

I’ve got a few disagreements, here, but let’s talk about Jim Ford for a minute, first.

“Harlan County” is the song most people think of when they hear the name Jim Ford. It came out in 1969. It’s a good example of southern soul music and it’s a great song. Jim did not invent this wheel. In fact, he was pretty late to the party because it seems like he spent the previous seven years doing his best imitation of whichever artist happened to be the big thing.

Listen to the song “College Queen” to hear what Jim sounded like in 1962 – basic pop and a fake accent. When Jim Ford pops back up in 1967? It’s with a Bob Dylan impersonation that is frankly embarrassing to listen to, in the form of a song called “Ramona.” Again, 1967 is the year “Ode to Billie Joe” came out and “Ramona” is what Jim Ford, the supposed secret author of “Ode to Billie Joe,” was doing at the time. But he also happened to be dating Bobbie Gentry at the time, which some people think supports Jim’s claim that he wrote the song.

Here’s a fact about Jim Ford: he was a cocaine addict.

Jim had a reputation for writing a song and selling it to as many producers around town as he could until someone realized they’d all bought the same song and it was now essentially worthless. There’s another story about Jim pretending to be too drunk to function in a recording session because he’d already sold all his songs to other producers and didn’t have anything he could record.

Before Barry White was Barry White, he was an A&R man for a small label in Hollywood. Barry remembers Jim Ford bringing Bobbie and “Ode to Billie Joe” to him and trying to sell the song for $50. Barry loved it but his boss didn’t so they turned it down. Now, if Jim Ford wrote “Ode to Billie Joe” and thought so little of it that he was prepared to sell it for $50… Why, after the monumental hit it became, why didn’t Jim spend the rest of his life churning out more versions of this song to make millions of dollars as Bobbie Gentry did?

People who think Jim wrote the song like to say Bobbie never wrote another song like “Ode to Billie Joe.” These people either haven’t listened to much of Bobbie Gentry’s music or their definition of a song like “Ode to Billie Joe” is a song with a MacGuffin in it. We’ll get to the rest of Bobbie’s music in a minute but, I should say, I’m a fan of Jim Ford’s music. I’m very familiar with it and he never in his life wrote a song anything like “Ode to Billie Joe.” The only similarity I can see in his work is drawing images from live in the South but when you take a look under the hood, there’s a completely different engine in there. So, let’s pop the hood.

The vast majority of Jim’s songs follow a simple pop songwriting formula. You could even use the word “trite” to describe most of them. Here are some song titles: “She Turns My Radio On,” “I’m Ahead If I Can Quit While I’m Behind,” “I’m Gonna Make Her Love Me,” “Dr. Handy’s Dandy Candy.” These are mostly good songs but even the best of his writing is a completely different style than Bobbie Gentry’s. You never get the idea that Jim is alluding to something other than precisely what he’s telling you.

The song “Harlan County” has this lyric in it: “Big Jack caught Daddy cheatin’ and he shot him over 15 cents to buy a loaf of bread with.” There’s two entire crimes laid out in one line with perpetrator, victim, and their respective motives described, down to the penny. That’s not even in the same universe as the restraint and narrative control on display in “Ode to Billie Joe” and this level of detail is highly typical of Jim Ford’s songwriting.

Jim Ford’s “Big Mouth USA” has this verse: “just last Wednesday, me and Judy Hensley was down by the river side / Ol’ Widow Brown came ogling around and told the biggest lie around town / you’d have thought Judy was going to have a baby, come Saturday night / and all we was doing was hugging and kissing down by the river side”

See? He has to explain everything in detail. He just can’t help himself. If Jim Ford wrote “Ode to Billie Joe,” we would all know exactly what was thrown off the bridge, exactly when and exactly why.

Here’s what else we know about Jim Ford. When Jim ended up working with Bobby Womack, they were always arguing because Bobby Womack got tired of Jim trying to tinker with Womack’s songs just to get a co-writing credit. Womack would go record the song without waiting for Jim’s notes and Jim would claim the song was stolen away from him. If anything, Jim Ford probably tried something similar with “Ode to Billie Joe.”

Add in the fact that Ford never made any attempt to bring a lawsuit against Gentry or Capitol Records, even after Bobby Paris successfully did so to get his 1% of the song. Add in the fact that the only song on her first album not written by Bobbie Gentry is a song by Jim Ford and the Vegas brothers, who are all given total credit for their work. One of Jim’s closest friends at the time said he thinks Jim was straight up trying to take credit for Bobbie Gentry’s song. The allegations of Bobbie Gentry stealing this song just do not add up.

I love Jim Ford’s music. He was a talented man but it’s time to put this rumor to bed. Jim Ford did not write “Ode to Billie Joe.” A young woman in her early 20s named Bobbie Gentry wrote that song.

Of course, the lifespan of the rumor is not at all surprising. The pop music industry is just as sexist as the country music industry. Jim is not the only man given credit for Bobbie Gentry’s work.

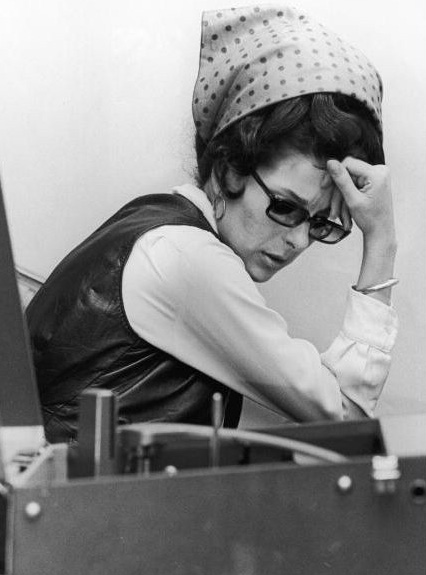

In the Control Room

According to Bobbie, she was always the real producer of her own sessions, even though a man’s name would always end up with that credit on the label of the record. The string arranger? Jimmie Haskell? He’s a great source of information for this time period. With all the drama, Jimmie’s one of the few people with no reason to lie about what happened. In interviews, he’s also maybe the only man who tries to downplay his role in “Ode to Billie Joe,” even though he played a bigger part than anyone besides Bobbie herself.

Capitol Records knew they were following up the single with a full-length album, so they had Haskell back in the studio with Bobbie before the “Ode to Billie Joe” single was even released. Back at their first meeting, Haskell remembers thinking Bobbie was soft-spoken (and he remembers thinking she had the most beautiful legs in the world). As she grew more comfortable in the studio, Bobbie began speaking up, giving production notes on how she thought her music should sound. Producer, Kelly Gordon – who would soon fall madly in love with Bobbie, leaving his family to try and convince Bobbie to marry him – you can imagine he would be inclined to let her have her way.

The full-length album Ode to Billie Joe is mostly built on top of that original demo tape made with Bobby Paris. Demo recordings were not meant for public consumption. They were about capturing the main idea of a song for all the behind-the-scenes decision makers. A song where the lyrics are the main attraction will often be demoed with nothing but a voice and one other instrument, like a guitar or piano. A demo like “Mississippi Delta,” where it’s about a musical vibe, that type of demo will have more going on. Bobbie’s first demo tape was nearly entirely about the lyrics. As a result, her first album, built on top of that demo, gets pretty repetitive. That little bossa nova guitar strum may not have been the only thing she knew how to do with a guitar but, listening to the whole album, it sure sounds that way. The same strumming pattern is in nearly every song and Haskell’s arrangements can only do so much to hide it.

By the way, Haskell and Bobbie went out on a couple dates. Though nothing much came of it, he does relate two things Bobbie said to him. After “Ode to Billie Joe” became a hit but before she was actually paid any of the money from it, Bobbie called Haskell to get the string arrangements for her Ed Sullivan appearance. She told Jimmie that it was freezing in her place because she hadn’t been able to afford to pay her gas bill and the company turned it off. Another time, before that, she told Jimmie her plans for life, “Jimmie, I’m gonna be rich. My mother’s been married twice – once to a regular guy and then to a rich man. I like being rich. If I don’t make it in music, I’m gonna start a company and make really inexpensive dresses out of burlap bags.” Obviously kidding around a little but something she said in a 1970 interview fits in here. Bobbie was talking to the famous Boston Globe writer Marian Christy about what it meant to be a successful artist:

Success is recognition and an open channel for creative energies. But I’m tired of hearing artists say they don’t perform for money. Fame without fortune is empty.” – Bobbie Gentry

When those “Ode to Billie Joe” checks did start showing up (with commas), Bobbie made very smart real estate investments. She was also one of the original owners of the Phoenix Suns basketball team, from 1969 to 1987. Her sense for business served her well when the recording industry did not.

The Chameleon

It’s impossible to say what would have happened if Capitol chose a different song for Bobbie’s follow-up single. They picked “I Saw an Angel Die,” which did not play into their marketing of Bobbie as a barefoot country girl from Mississippi. You’ve gotta think they’d have been better off reissuing “Mississippi Delta” as an a-side, since that’s what got them interested in Bobbie in the first place, or the other standout on the album “Papa, Won’t You Let Me Go to Town with You.”

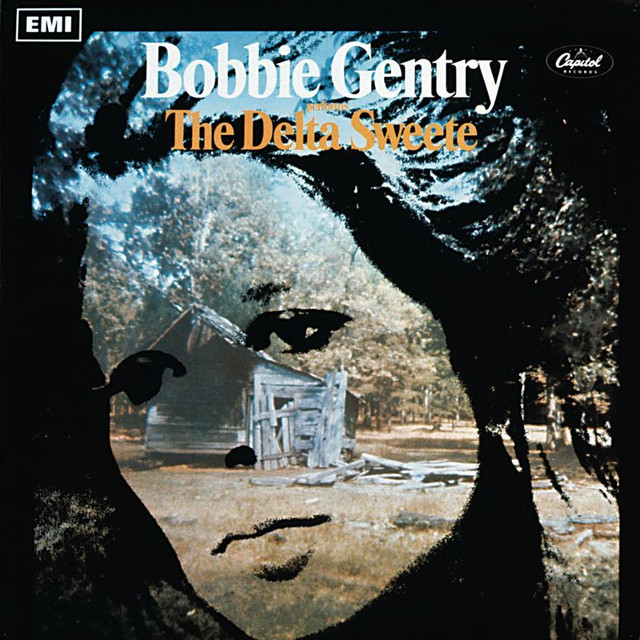

Anyway, when the second single on her first album gained no traction, Capitol rushed Bobbie right back in the studio to make a second album. Her first full-length came out in August of 1967. Her second album, The Delta Sweete, was on sale, in stores, in March of 1968. They were clearly shooting for a followup hit before the public forgot about Bobbie Gentry. It could have worked, if she had any interest in repeating herself.

We can assume Kelly Gordon, a company man, would have tried for another hit like “Ode to Billie Joe,” if he ran The Delta Sweete sessions, as it says he did on the label. On the other hand, if you consider the possibility that this is the first time Bobbie’s had a full major label recording studio and session musicians at her disposal, the drastic change that takes place in her music right here, it makes a lot of sense. Bobbie’s guitar strum does show back up, here and there, but the overall production style is what you would call “kitchen sink.” The Delta Sweete is wildly different from her first album. Again, it’s not country music but this time it’s not really pop music either. It’s more like what a Broadway musical about country music would sound like or if The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper had fought for the confederacy. You’ve got abrupt shifts in tempo, a kaleidoscope of voices talking, singing and laughing all over the mix and weird orchestral interludes between Bobbie’s covers of blues and country music standards. It’s extremely ambitious, more than a little pretentious and wonderful.

Running through the first three songs real fast…

The album opens with the first single, “Okolona River Bottom Band.” The lyrics seem to be some nonsense about a band holding auditions for new members but Bobbie’s very sexual delivery and a pun on her own last name hint toward these auditions being for something else entirely. That song rides an “Ode to Billie Joe” violin swell into “Big Boss Man,” which Bobbie also gives a sexual overtone with her delivery of the line “Gonna get myself a boss man…” And it gets even weirder from there with track 3, a vocal collage titled “Reunion,” which many of you heard in the second season of Fargo.

Then, there’s an I-don’t-even-know-what-to-call-it mashup of traditional gospel songs called “Sermon.” My favorite track is the closer – a lush, looping piece called “Courtyard.” If you can’t tell, I highly recommend this album. Listen to the whole thing. You’ve never heard anything like it before. If it was put out as Bobbie’s third or fourth album, I think it could have been a hit. Releasing it less than a year after “Ode to Billie Joe,” telling fans to forget everything they thought they’d learned about this woman’s music just seven months ago, probably not the best idea.

The Delta Sweete didn’t have a hit on it. Capitol Records doubled down on their strategy. 7 months later, in October of 1968, Bobbie’s third album came out. It was called Local Gentry. If we could go back in time and put The Delta Sweete on a shelf for a few years, Local Gentry’s release date and musical content would make perfect sense as her second album. Production wise, it’s a scaled back, less zany and less-interesting-by-comparison-but-you-don’t-know-that-because-you-haven’t-heard-it version of The Delta Sweete. Where The Delta Sweete mashed up country/blues standards and sweeping, schizophrenic production without explanation, Local Gentry includes three Beatles covers to let us know where Bobbie’s coming from. Unfortunately, The Delta Sweete had happened and Local Gentry wasn’t enough to win her audience back. Fortunately, Capitol Records had given themselves an insurance policy this time.

Glen Campbell, also signed to Capitol, had finally hit in 1967 with “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” and another one in March of 1968 with “I Wanna Live.” Now, remember that The Delta Sweete came out and bombed in March of 1968 and it’s not hard to see Capitol Records’ logic in their next move – “Hey, let’s take this country/pop guy who’s not looking like a one hit wonder and put him with the pop girl we’ve been unsuccessfully marketing as country and see if he can help her out.”

It worked.

The Bobbie Gentry and Glen Campbell album came out a month before Local Gentry, in September of 1968. The single, “Let It Be Me,” went to the Top 20 on country charts and even made it to the Pop Top 40. Bobbie’s next solo album, the excellent Touch ‘Em with Love, was recorded in Nashville. Listen to the title track for a phenomenal example of Southern soul music, a glimpse at the direction her career could have gone with “Mississippi Delta” as her second single. Yet another flop.

In 1970, she was back with Glen Campbell for an even bigger hit than their first single, “All I Have to Do Is Dream.” Despite it sounding like a karaoke backing track or like The Everly Brothers didn’t show up for their recording session and the producer decided to just go with the background singers. This went to #6 on the country charts and #27 on the pop charts.

By this point, it had to be virtually impossible to keep up with who Bobbie Gentry was supposed to be or what she was supposed to sound like. Girl with a guitar? Sgt. Pepper of the Swamp? One half of a Disney Pop Duet? The female Wilson Pickett? I’m not so sure any one of these Bobbie Gentry’s is more real than the others but the general public has met all four of them within three years of becoming aware of her existence. Playing with your persona is fine but first you have to have a persona to play with. Even David Bowie gave us a few years to get to know him before introducing the world to Ziggy Stardust. Following her initial hit, Bobbie’s only real commercial success could be attributed to Glen Campbell’s rising star as much as anything else.

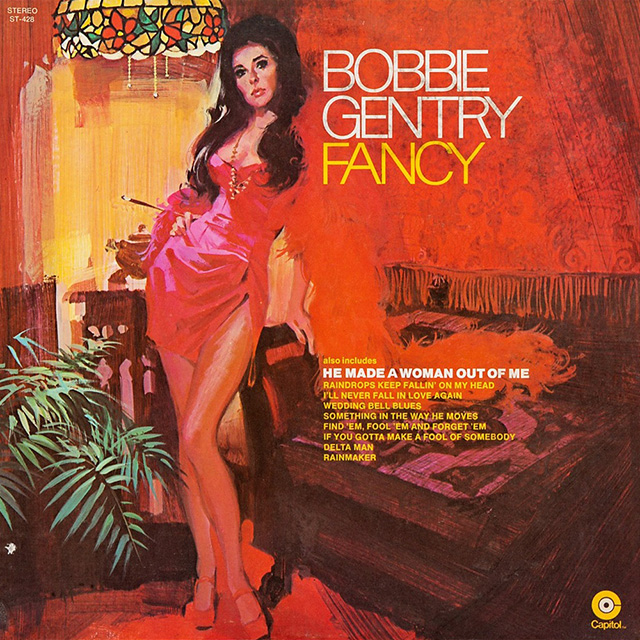

Paydirt

That being said, in May of 1970, all these versions of Bobbie Gentry showed up at Fame Recording Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Studio owner and producer, Rick Hall, was at the control board for this one. I don’t know if he got a whole album of what he wanted out of Bobbie but he got a song. The title track would be her second biggest hit as a solo artist and a Top Ten Country hit, 20 years later for Reba McEntire, called “Fancy.”

It’s the only song on the album written by Bobbie and, according to Rick, he special ordered it. When Bobbie asked Rick to produce her album, she asked what he needed from her. Rick told her to write another “Ode to Billie Joe.” That’s not exactly how I would describe Fancy but it’s certainly another impressive example of Bobbie’s songwriting ability, another great story that had not been told this way.

To put it bluntly, we meet an eighteen-year-old girl who gets turned into a prostitute by her own mother… and she’s glad that happened because she’s done great for herself. This is not some Pretty Woman, “hooker with a heart of gold” who needs a man to save her with his love. Fancy gets into the game, makes enough money that she now owns her own mansion in Georgia and a townhouse apartment in New York and, if she’s still in the game, it’s gotta be because she enjoys it because she hasn’t had to worry about money in 15 years. The story is epic. The production is the secret weapon.

Scattershot drums hit a bullseye Bobbie’s been aiming at since The Delta Sweete. Jimmie Haskell’s “Ode to Billie Joe” strings are back in a heavy way and Rick Hall’s horn section is the actual definition of southern soul music. This one song contains most of Bobbie Gentry’s personalities and, for four minutes and fifteen seconds, it all adds up. It’s very southern. It’s larger-than-life. It’s funky and it has mainstream appeal. The single went to #26 country and #31 pop. Bobbie had another hit on her hands.

Of course, the second song on the album is a Burt Bacharach cover but, don’t worry, that’s also great. She’d actually already done “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again” on Touch ‘Em with Love but, at that point, American radio listeners were being introduced to a new Bobbie Gentry every 7 months. They didn’t go for it. In England, where Bobbie’d been hosting a BBC variety show since 1968, that Bacharach cover was a huge hit. She recycled it on the Fancy LP and added another Bacharach cover but American audiences still weren’t into it.

The next album, her seventh solo album in five years, would be her last.

Nothing to Do for an Hour or Two

Released in 1971, Patchwork is the only Bobbie Gentry album where she’s given full credit as producer of every song.

Like everything that happens when Bobbie’s in charge, it’s theatrical. The overall sound is something like Burt Bacharach’s score for Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid but if it was Kate Bush and the movie was, like, a Robert Altman ensemble piece instead of a western. Most of the actual songs are simple character studies, named for their subjects (“Benjamin,” “Billy the Kid,” “Beverly”) and connected by little musical interludes.

The closing track, “Lookin’ In,” has since been interpreted as a goodbye note to the recording business. That seems accurate. The song ends with some thoughts about “sacrifice” being the ugliest word Bobbie ever heard. It implies the one compromise “that would be one too many for her” would be to blame somebody else for her state of mind. There are many ways to read that but, to me, it sounds like she’s tired of sacrificing her artistic vision. As for the “compromise” part, well – in a sense, compromising your art lets you off the hook. If and when the final product doesn’t work, you get to blame the person who talked you into compromising. Jimmie Haskell says, toward the end of her time there, Bobbie had developed a reputation at Capitol for being difficult to work with. He says, “By this time Kelly Gordon was ill and not working with her. The A&R folks felt she was not worth worrying about.”

If we allow ourselves to read between the lines, here, and take Bobbie at her word that Kelly Gordon was letting her run sessions while he took credit, then it looks like the producer who came after Gordon wasn’t down with that arrangement. Bobbie being an artist (and a woman on top of that), this would be seen as her being “difficult.” Whether it was Capitol or Bobbie who did decide to sever the relationship, we get the same outcome: Bobbie, no longer making records, focused her attention on the award-winning, attendance record-breaking, multi-million dollar Las Vegas shows she’d been producing since 1968.

From all the way back to when she had smaller dreams of being a songwriter behind the scenes of the industry, Bobbie’s interests reached outside of music. In those early days, while working as a secretary in Los Angeles, she attended UCLA as a Philosophy major with some Art classes on the side. If you look at the album covers of Fancy and Patchwork, it’s widely believed that Bobbie Gentry did those paintings herself. In Las Vegas musical theater, Bobbie found a medium where she could take more control, fully realizing her ideas without compromise.

The final episode of this season will really get into how much of a role off-Strip Las Vegas played in keeping real honky tonk music alive in the ’50s and ’60s. The showrooms on The Strip were for more extravagant entertainment – showgirls, costume changes, choreographed dance routines and a big ticket name on the marquee to fill up the seats. You know, showmanship. Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack moved in during the early 1950s and Las Vegas became a place where entertainers of a certain caliber could cash gigantic paychecks with residencies on the strip. And, if you could keep selling tickets year after year, then you could just move to Vegas, stop touring entirely and completely erase from your life issues like missed flights, tour bus accidents, audio problems in unfamiliar venues, sketchy promoters, early morning radio… I could go on…

Viva Las Vegas

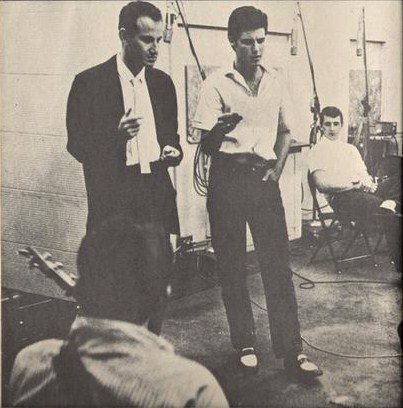

Back in 1967 and 1968, the big names just then arriving to Vegas include acts like Tom Jones, Siegfried & Roy, Elvis Presley and, riding the wave of “Ode to Billie Joe,” Bobbie Gentry.

Maybe she started small with a show built around her playing guitar and piano and singing her own songs. We don’t really have a lot to go on for the early years but, based on reviews of her shows, it’s safe to say it didn’t take very long for her to start finding more and more extravagant ways to spend that production budget. Every premiere of a new show run has people wondering what she’ll do next. Smoke machines simulate pond fog as a gondolier rows her across the stage in a boat. Trapdoors in the floor give her a disappear/reappear act. Rainclouds create storms with real water in the middle of the show. We’re not just talking about shiny clothes, here. Although, if you want to talk about that, a big selling point for one of her shows was a Levi’s jeans-and-jacket combo with over a million dollars’ worth of Tiffany diamonds sewn on before every performance. You could even watch a security detail transport the diamonds from a vault to the dressing room each night.

All these things may sound like typical aspects of Las Vegas shows now but Bobbie had a big hand in setting these trends. The choreography and direction of her shows were usually outsourced but nearly every other detail was planned by Bobbie herself – including the decision to have male dancers come onstage in female clothing, way before things like that became mainstays on The Strip.

Bobbie did an Elvis Presley impersonation that was apparently quite a thing. Word of her Elvis act quickly spread around town. The King is rumored to have waited until the house lights went down one night in order to sneak in the back of the theater and watch the show himself. The gossip goes that he worried it was more of a parody than a tribute. After seeing Bobbie’s great homage to him, Elvis began plugging it from his own stage, telling his audience to make sure and go see Bobbie Gentry before leaving town. This led to Bobbie taking part in several of Elvis Presley’s famous late night hotel room jam sessions, which, of course, led to tabloids printing rumors of a romance between Bobbie and Elvis. She let it slide until one magazine manipulated a photo to make it look like she was pregnant and ran it on the cover with a headline reading: BOBBIE GENTRY TO HAVE ELVIS’ SON!

She took the magazine to court and won a $2,000,000 settlement. This happened in 1974, so it was after she’d quit making music for Capitol Records but her relationship with the media had been rocky from the start. For one thing, they almost always misrepresented her as some kind of smiling idiot, getting ahead in life on her looks, which could not have been further from the truth.

Ain’t Sayin’ She a Gold Digger

Back in late ’69, while she was still moving between casino showrooms in Vegas, Reno and Lake Tahoe, Bobbie married Bill Harrah. That’s “Harrah” as in Harrah’s Casino. Bill was about 30 years older than Bobbie. So, even though she was already a millionaire and making millions more on her own every year, the common perception of the relationship was exactly what you would expect. When the marriage lasted only four months, papers reported it as “singer, Bobbie Gentry,” divorcing “millionaire, Bill Harrah,” burying the lede that the separation involved no alimony and no property settlement.

From then on, Bobbie was treated as a gold digger. When Bobbie sued that tabloid for completely fabricating photographic evidence of her being pregnant by Elvis, it was a knockout punch delivered in response to years of taking jabs on the chin.

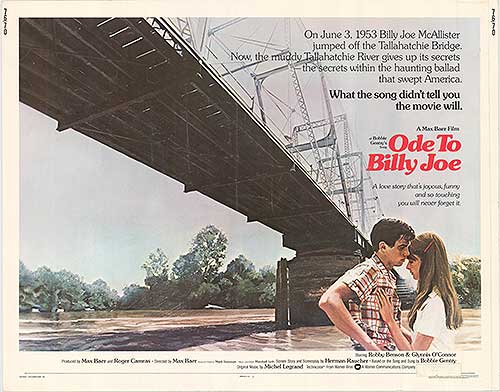

The same year as the Elvis thing (1974), a movie called Macon County Line came out. It was written by and starred Max Baer Jr., who you know as Jethro from the original Beverly Hillbillies. Directed by Richard Compton, who’s since done episodes of dozens of TV shows you’ve also seen, Macon County Line is a pretty typical “murder in a small town” revenge sort of movie. But it was presented as a true story, which it wasn’t, and drive-in theater audiences ate it up. It may have been the single most profitable movie of 1974, grossing $30,000,000 worldwide on just a $225,000 budget.

The theme song for Macon County Line is called “Another Place, Another Time.” When they hit her up to do the song, Bobbie said she’d have to see the movie first and would only do it if she liked it, which she obviously did. So, when the movie that she liked, made by people who she knew, came out and did really well financially, she decided to see what they thought about turning her hit song “Ode to Billie Joe” into a movie. She’d had the idea for a long time, a no-brainer, really.

See, Bobbie initially wrote “Ode to Billie Joe” as a short story. That’s how “Fancy” was written, too, by the way. Given the depth of character in many of her songs, it’s possible Bobbie Gentry is secretly one of the great unpublished short story writers of our time. A movie adaptation of such a big hit was sure to turn a profit, even nearly ten years after the fact, especially with this particular song as the source material. They could market the movie as the answer to The Big Mystery after all these years! That’s what they did, too, right there on the poster: “What the song didn’t tell you, the movie will.”

Many fans wished they’d let the mystery stay a mystery because what happens in the movie is completely out of left field…

Herman Raucher was brought in to write the screenplay. In a 2002 interview, Herman tells the story of meeting with Bobbie Gentry, asking her why Billie Joe MacAllister jumps off the bridge and Bobbie tells Herman that she has no idea. Again, that’s not the point of the song. It’s not why she wrote it and it’s a perfectly acceptable response. But, now, Herman is left holding the bag and my guess is he decides to come up with the most convoluted and unexpected reveal that he possibly can because here’s what happens in the movie…

The female lead, who we know as the narrator from the song, is named Bobbie. This movie does the same thing as Macon County Line, where it insinuates that it’s based on a true story, so a lot of people were made to think this Bobbie character is supposed to be Bobbie Gentry. Bobbie and Billie Joe MacAllister are young teenagers in the 1950s and they’re dating, though Bobbie’s father doesn’t approve. This all fits with the song, so far. No surprises, yet.

Now this Billie Joe MacAllister kid is one horny little dude and he’s always trying to get Bobbie to go all the way. It looks like we’re headed for a baby-off-the-bridge scenario but, no. Bobbie hangs on to her virginity and Billie Joe hits up a party to get drunk, cut loose and, we assume, bang a hooker. Except it turns out we cut away from the hooker scene a little too early because, the next day, Billie Joe’s disappeared. He stays missing for a couple days. By the time he comes back, Bobbie’s decided she’s ready to have sex with him but, now, Billie Joe can’t make it happen. He starts crying and – get ready people, cause here it comes – Billie Joe tells Bobbie that, after the jamboree, he had sex with a man – his boss from the sawmill. That’s why he jumps off the bridge to kill himself.

Of course, there’s more to the plot than that but there’s the big reveal. That’s what everyone bought a ticket to see. Oh, and, the thing the preacher sees Bobbie and Billie Joe throwing off the bridge?

It’s Bobbie’s childhood rag doll she wanted Billie Joe to have for some reason.

If you’re bummed out right now, remember this feeling the next time an artist tells you to enjoy the mystery of not having all the answers. Despite mixed reviews and a plot that turned off many viewers in the intended demographic, the movie seems to have done really well. One more revenue stream for Bobbie Gentry, who by this time had to be an incredibly rich woman.

Lookin’ In

A couple years after the movie, in 1978, Bobbie met Jim Stafford in Las Vegas. He was brought in as an opening act for her new show at the Aladdin. This is five years after Bobbie’s record deal with Capitol came to an end. Jim had already done his biggest hits, “Spiders & Snakes” and “Wildwood Weed.” But, when it came to Bobbie Gentry in Las Vegas, yeah, Jim was still an opener, although the show got bad reviews in the local press.

Attendance was way down from Bobbie’s days of breaking showroom sales records. Still, Bobbie and Jim got to know one another by working together. When she learned the details of his publishing and recording contracts, Bobbie told Jim that he needed new management. Apparently, she also thought he needed a new wife. They were married within six months. There are rumors that they began working on an album together but we’ll probably never know if that’s true or not. According to IMDB, they were both on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show for his 1978 Christmas episode. I have no idea if they performed together or not.

Like her first, the marriage to Jim Stafford didn’t last long. Soon after having a child together, they divorced. Again, Bobbie would take no alimony and the split seems to have been as friendly as these things can be. Years later, Jim would still describe himself as a Bobbie Gentry fan.

The same year she met Jim, Bobbie went back into the studio with Rick Hall from Muscle Shoals to record a couple of covers. “Steal Away” by Jimmy Hughes is a great song but the production on her cover of it is way over the top and not in a good way. As always, it’s hard to know if it’s Rick or Bobbie to blame but the restraint you heard in their previous collaboration on “Fancy” is not here. The vocal effects are out of control. The horns are heavy-handed. It isn’t surprising the promo single failed to do anything with radio. If there were plans for a full album, those plans were scrapped. As of late 2017, “Steal Away” is the last Bobbie Gentry release.

Her final performance in Las Vegas was in September of 1980.

In May of 1981, NBC put on a special called The All-Star Salute to Mother’s Day. Bobbie did a song and dedicated it to her own mother, Ruby, who was in the studio audience. This is likely Bobbie’s final public performance.

Her last major public appearance was either at the 1981 or 1982 Academy of Country Music awards.

After that: nothing.

And it’s not like she just stopped going to awards shows. There are friends and family members who say they’ve had zero contact with her since her retirement. The so-called disappearance of Bobbie Gentry has become a mystery all on its own. The rumors of what she’s been doing are all over the place.

In 1983, she was supposed to have been scheduled to appear somewhere with Mac Davis but then canceled at the last minute. Some people think she’s been recording music without releasing it. Some people think she’s been writing songs under a pseudonym and we’ve been hearing other artists perform her work on the radio this whole time.

Her old string arranger, Jimmie Haskell, says he got a call from Bobbie in the late ’90s. She wanted him to get to work on a new song right away but he was too busy with previous obligations. She never contacted the person he recommended and he never spoke to her again.

In June of 2016, a reporter from The Washington Post tracked Bobbie down through some real estate paperwork. He made a call to what he believes to be her personal residence. A woman answered by saying “hello” and then told him there was no one there by the name he requested, the name listed as the owner of that property. As he began to respond, she hung up on him.

Bobbie Gentry’s retreat from the spotlight isn’t a mystery to me at all.

I believe every piece of information you need to figure out why she went away is in this episode of Cocaine & Rhinestones. Maybe you just missed something? Perhaps you should go back and read it again?

Oh, and, there’s one more thing about fame. Some people say it’s the closest thing to immortality, here on earth. You can be dead and gone but as long as people remember you, listen to your voice, look at your image, tell your story – some part of you stays alive.

I assume Bobbie Gentry will live forever.

Thank you so much for listening to and reading Cocaine & Rhinestones. Every episode is written and produced by me, Tyler Mahan Coe. You can follow me on Twitter or Facebook.

Please share this episode or blog post with one person. You know a person who will like it, so let them know it exists.

Next week on Cocaine & Rhinestones is a complete and total examination of one Merle Haggard song, “Okie from Muskogee.” Whatever you think that song is about, I think you could be wrong. But you’ll need to hear about The Great Depression, The Dust Bowl and all sorts of other things to make an informed decision. Hopefully, you’re subscribed to the show and you’ll hear that right when it comes out.

You can also leave me a good review on iTunes or Stitcher if you’d like to be entered in the giveaway I’m running for this season. I have all these books I had to read to make the show and I’m not going to read them again, so I might as well give them away. Now, full disclosure, I have not treated these books very well. I fold the corners of the pages. I draw little symbols in the margin and, sometimes, I even write full sentences in the books, sometimes curse words. So if you’re just wanting to read the books I read then you should get new copies for yourself. But, if you’re enjoying the show and you’d like to have a piece of memorabilia from the first season, then go to Cocaine & Rhinestones in the iTunes store, or Cocaine & Rhinestones on Stitcher, leave a review, take a screenshot and email it to giveaway@cocaineandrhinestones.com to enter. I will be randomly selecting winners on January 30th, 2018, which I think is the day I’ll be ending this season with a Question and Answer episode. You can participate in that by sending what you want to know to questions@cocaineandrhinestones.com BONUS: Cocaine & Rhinestones Season 1 Q&A Episode!

-TMC

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [linked, if available]:

- Heinz Roemheld – “Theme from Ruby Gentry” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Ukulele – “Jungle Song” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jody Reynolds – “Endless Sleep” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jody & Bobbie – “Requiem for Love” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Yardbirds – “Heart Full of Soul” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobby Paris – “Night Owl” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Mississippi Delta” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Ode to Billie Joe” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Lou Donaldson – “Ode to Billie Joe” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Kanye West – “Jesus Walks” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- A Tribe Called Quest – “Clap Your Hands” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Lauryn Hill (ft. Carlos Santana) – “To Zion” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Drake – “5am in Toronto” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Eminem – “Bad Guy” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dr. Dre ft. Snoop – “Smoke On” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jim Ford – “Harlan County” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jim Ford – “College Queen” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jim Ford – “Ramona” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jim Ford – “Bigmouth USA” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Bugs” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “I Saw an Angel Die” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Papa, Won’t You Let Me Go to Town with You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Okolona River Bottom Band” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Big Boss Man” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Reunion” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Sermon” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Courtyard” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Casket Vignette” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Eleanor Rigby” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry & Glen Campbell- “Let It Be Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Touch ‘Em with Love” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry & Glen Campbell – “All I Have to Do Is Dream” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Fancy” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Benjamin” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Billy the Kid” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Beverly” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Lookin’ In” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Another Place Another Time” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobbie Gentry – “Steal Away” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Excerpted Video

These may be removed from YouTube in the future (for any of a number of reasons) but, for now, here they are:

Commentary and Remaining Sources

I did want to make sure to say that I am in no way pretending to be above celebrity and fame culture. This is a podcast where I spend hours talking about celebrities, so, yeah. Speaking of talking for hours, I’m sorry if my voice being shot made the episode not as good for anyone. I set a schedule for this thing and if I don’t stick to it then it all falls apart.

This episode was a lot of fun because there’s really just not that much to go on except verifiable facts like record release dates and such. I don’t want to talk much more about the process of why that’s fun for me but it becomes a game of what to reveal and when to reveal it that keeps it engaging for me.

Like, the tape at the beginning.

That’s obviously Bobbie Gentry singing into a low budget tape recorder. (I don’t know if someone tried to record over it – or maybe she did that, maybe she was just experimenting with a tape recorder. I used to do that when I was a kid, so maybe that’s what she was doing.) That tape comes from a guy named Bryan Holley, who I think is actually related to Bobbie Gentry, so he’s got, just, a box of her stuff? But he hasn’t talked to her since she disappeared. He gets interviewed in the only book I could really use as a source for this episode, which is Tara Murtha’s Ode to Billie Joe entry in the 33 1/3 book series.

Tara went and hung out with this Bryan Holley guy and talked to him about what it’s like to have this box of Bobbie Gentry’s stuff just sitting in his house. Then, I found an NPR article [I guess it wasn’t on NPR but a local public radio station. See link at end of Liner Notes.] where they must have gotten the tape from Bryan and put it in the article. That’s how I was able to find that and use that. I love things like that. Any sort of found footage, found tape, anything like that – if I ever find things like that I will almost always use it. There’s just something unedited about it that feels like a rare moment that you get to be in on. I hope that worked for you. I could see how it wouldn’t work for some people but it works for me.

Okay, please, believe me when I tell you that I am extremely aware of the very prominent theory of what is in the briefcase in Pulp Fiction. Yes, I gave some light spoilers for a couple of old and relatively obscure films in this episode but I do not think it’s fair of me to assume that everyone who wanted to listen to a podcast on Bobbie Gentry also wanted all-but-confirmed spoilers for a much more recent and much more popular movie. I don’t need tweets about what was in the briefcase.

If you really can’t let the MacGuffin thing go, I did find an early interview with Bobbie (before she figured out that she should shut up and let the hype build) where she says she thinks it was something like a ring or a locket that they threw off the bridge, something to symbolize the end of an engagement. So, there you go. She doesn’t definitively say that’s what it was. She says “she thinks,” implying that it’s open for interpretation still but you can hold on to that as The Big Secret if you want.

This is supposed to be one of those songs where nobody knew the race of the singer when it first blew up. “Ode to Billie Joe” was so popular that basically every genre of radio station played it – R&B/Soul, Jazz, basically any station with songs that have singers (so, Not Classical) – and the song went to the Top 20 on the chart of every genre with stations that played the song. That’s above and beyond a crossover hit. That’s monumental. That is legendary. We will be talking about this song forever. For as long as people care about sounds made by other humans, we will be talking about “Ode to Billie Joe.”

That being said, not everyone loved this song. Apparently, Bob Dylan hates it. Apparently, Bob Dylan hated the song so much that he wrote a parody of it, released as “Clothes Line Saga” on the Basement Tapes. The working title was “Answer to Ode.” I’m a Bob Dylan fan but I find it unlistenable.

Macon County Line did so well they made a sequel, called Return to Macon County, starring Nick Nolte and Don Johnson. Also, Ruby Gentry, the movie Bobbie took her name from, is directed by King Vidor. (He made amazing movies, if you’re not a film person.) That movie is not just some random oddity. You should watch it. It’s a really good movie.

Bobbie was in the music video world really early. She played “Ode to Billie Joe” on some local TV show in Atlanta and Capitol bought the rights to the tape, so they could do whatever they wanted with it. They sent it to Ralph Emery, who played it on his WSM TV show. It got such a big response from viewers that Capitol sent copies to 40 other TV stations and decided to start making videos for all their artists. I read this in Buck Owens’ autobiography because his producer at Capitol, a man I’ll be talking a lot more about, named Ken Nelson, told Buck about it and Buck started making music videos, too.

Alright, that’s it. See you next Tuesday. “Okie from Muskogee”

Whatever Happened to Bobbie Gentry? – Washington Post

On the Record with Grammy-Winning Arranger, Jimmie Haskell – Medium

Fan Finds Unreleased Recordings, Possibly by Vanished Pop Star – SCPR [This headline is misleading. Bryan Holley’s father married Ruby Gentry, Bobbie’s mother.]