[DISCLAIMER: This episode of Cocaine & Rhinestones tells an extremely disturbing story. This is not suitable content for children or anyone who shouldn’t read a graphic and detailed account of torture and murder.]

Spade Cooley came to California in the early 1930s, as poor as everyone else who did the exact same thing at the exact same time. Only, Spade became a millionaire. And all he needed to accomplish that was a fiddle, a smile and a strong work ethic. If it sounds like the American Dream, stick around to hear how it became an American nightmare of substance abuse, mental illness and, eventually, sadistic torture and murder.

If this episode doesn’t screw you up, you’re already screwed up.

Recommended if you like: Western Swing, murder ballads, My Favorite Murder, True Crime Garage (or any other “true crime” or “murder” podcasts, really), Tex Williams, Bob Wills, fiddles and having nightmares.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

In addition to The Library, these books were used for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

Murder Ballads

The word “ballad” comes from a Latin word meaning “to dance.” And, originally, ballads were written to be performed with dancers acting out the lyrics live, like a miniature ballet. “Ballet” comes from that same Latin word. Even after the art forms branched apart, ballads remained focused on telling a specific story through direct narrative.

Ballads have always been written largely by and for the working class. The type of stories you’d hear in medieval ballads are the same stories we tell ourselves in modern movies. You’d have ballads for your “Love Conquers All” romance, immature comedy, tearjerking tragedy, tales of heroic glory and, of course, murder ballads.

While the authors of traditional ballads go largely unnamed, most murder ballads can be traced back to the real killings of real people. Take “The Knoxville Girl,” for example. You may think of it as a Louvin Brothers song but we can trace the roots of this song all the way back to the year 1683, in England, with the murder of a young woman named Anne Nichols. Anne had become pregnant by a man named Francis Cooper and, rather than do the “honorable” thing by marrying Anne, Frank instead chose to kill her and their unborn child. This really happened. Two years after that crime, we have documentation associating this specific murder with a new murder ballad titled “The Bloody Miller.”

The Bloody Miller

“The Bloody Miller” would inspire many alternate versions of the same story, including one named “The Berkshire Tragedy,” which would morph into “The Oxford Tragedy,” then “The Oxford Girl,” then “The Wexford Girl” and so on – until crossing the ocean to America and eventually becoming “The Knoxville Girl.”

The lyrics of “The Knoxville Girl” do not give us much context for the slaying in the song. We’re told that there’s a boy and there’s a girl. It’s implied they’ve been seeing one other quite heavily for some time. They go for a walk one day and the boy picks up a stick and beats the girl to death while she begs him not to kill her. The boy then tries to lie about what he’s done but is caught and placed in prison, presumably, for the rest of his life. Where previous versions of the song tell us why this murder happened, “The Knoxville Girl” does not.

He just kills her.

And I don’t think I’ll ever be able to listen to “The Knoxville Girl” again without thinking of Spade Cooley…

Who Is Spade Cooley?

Every country music fan with more than a passing interest in Western Swing knows the name Spade Cooley.

It’s like a little bit of trivia for the genre.

There are two facts we associate with that name. One – Spade Cooley was “The King of Western Swing” long before that title was transferred to Bob Wills. Two – Spade Cooley murdered his wife.

But there’s a lot of story hiding in those two facts.

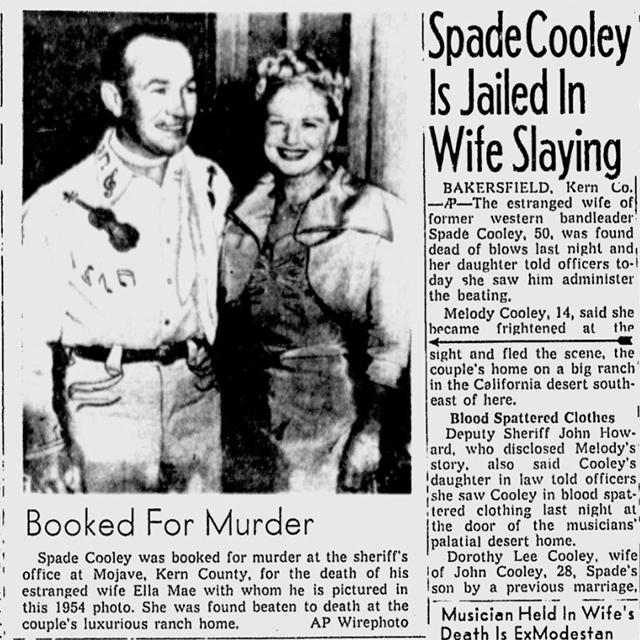

“The King of Western Swing” was more than just a cool nickname. For most of the 1940’s and 1950’s, Spade kicked as much ass as it was possible for a musician in Los Angeles to kick. It would be difficult to exaggerate his professional success. Not only does Spade Cooley have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame but at the height of his television show’s popularity it’s estimated that 75% of L.A. viewers were tuning in on any given night. Put it this way. In 1951, Frank Sinatra already had over 20 Top Ten singles to his name but his career wasn’t doing so hot anymore. He needed a comeback and part of his plan for that was a singing appearance on Spade Cooley’s hit TV show.

Looking back on it now, we can see things ended up working out pretty well for Frank Sinatra.

Spade Cooley, not so much. Because of that second little piece of trivia.

Now, I don’t know how so many people are comfortable using a simple word like “murder” to sum up Spade Cooley’s actions on the day of his wife’s killing. This was not a domestic argument that got out of hand. Not an accident with a dangerous weapon. Not a so-called crime of passion. This wasn’t even an isolated incident. It was a savage and deliberate execution which many people had to have seen coming.

Before we get too far into it to turn back around, consider this your warning: today’s story takes us to a very disturbing place. But we’ve got some other things to talk about first…

Meet Spade

The first 45 years or so of Spade Cooley’s life went more than alright.

Born 1910 in Grand, Oklahoma, with the name of Donnell Clyde Cooley, the official story is that Spade was one-quarter Cherokee. That’s backed up by his attendance at Chemawa Indian School in Oregon, where his family moved when Spade was 4 years old.

Spade’s father played fiddle at local dances and he hoped his son would one day find success as a classical cellist or violinist, a dream that Spade shared as a child and he took his lessons accordingly. Though his classical training did not lead to a classical career, it did eventually lead to paying jobs playing fiddle at local dances, just like his dad.

Performing music and doing a bit of amateur boxing seems to have occupied Spade’s time until he was around 18 years old, which is when he eloped with Anne, a full-blooded Inuk from school and soon-to-be mother of their son, John. A year deep into what is now known as The Great Depression, this young family would arrive in California with nothing but, and I’m quoting Spade here, “a fiddle under one arm and a nickel in [his] pocket.” The year was 1930 and, as it turns out, he didn’t have much to worry over…

Spade Cooley was always the kinda guy to make you feel like his best friend. He called every man he met “son.” He’d put his hand on your shoulder and a smile in your face. When he showed up for a job, he was there to work hard and make sure it got done right. Knowing his way around the fiddle like he did and the ability to sight read sheet music was enough to place Cooley at the top of several call lists for short-notice, pickup gigs. That “down home” good ol’ boy routine helped him move up the ranks of the Los Angeles music scene fast, which is how he came to play with the Jimmy Wakely Trio, Riders of the Purple Sage and Sons of the Pioneers.

Unless you go add it after listening to this, you won’t find Spade Cooley’s name on the Sons of the Pioneer’s Wikipedia page. To be fair, that legendary group is a bigger part of Spade’s story than he is a part of theirs. By the time Cooley came around, they’d already had their signature hit with “Tumbling Tumbleweeds” and the group’s breakout star, Roy Rogers, had mostly moved on to work in major motion pictures. But Roy would still come around every now and then. Someone pointed out that Spade Cooley bore a passing resemblance to Roy Rogers. Before you know it, Spade was bringing down some extra cash by serving as a stand-in for Roy on movie sets during the day, while still playing pickup gigs with multiple bands on the L.A. dancehall circuit at night. With one foot firmly planted in each of Southern California’s most desirable professions, Spade was about to find himself a very rich and very famous man.

King of Western Swing (Warner Bros. short)

The King of Western Swing

There’s a bit of disagreement over the origins of the term “Western Swing.”

In the late 30s and early 40s, that style of music became huge. It was Swing Jazz but played the only way it made sense to play it when featuring a steel guitar and taking cues from the fiddle player. It sounded just new enough that, when it came barreling out of the Dust Bowl, it hit Southern California as a full-blown dance craze.

In 1942, an L.A. area swing jazz DJ, named Al Jarvis, held a contest to see who was the best band leader in the country, a.k.a. The King of Swing. Jarvis probably expected one of the big band leaders like Harry James or Benny Goodman to win and he must have been surprised when Spade Cooley’s countrified take on the sound came out on top in the voting. Jarvis called Spade “The King of Western Swing.” The promoter of Spade’s concerts at the Aragon Ballroom jumped on this and was soon using “Western Swing” in advertisements for his shows.

But Bob Wills was playing Western Swing before an 18 year old Spade Cooley had even moved to California. It might have taken a while longer for someone to figure out what to call this new country/jazz fusion but Bob Wills was one of the guys who figured out how it should sound and he set up shop getting people to dance to it. From 1934 to 1943, Bob Wills and The Texas Playboys were packing as many as 6,000 people into Cain’s Ballroom in Tulsa, Oklahoma, while releasing national radio hits such as “Time Changes Everything,” “New San Antonio Rose” and “Take Me Back to Tulsa.”

Bob Wills

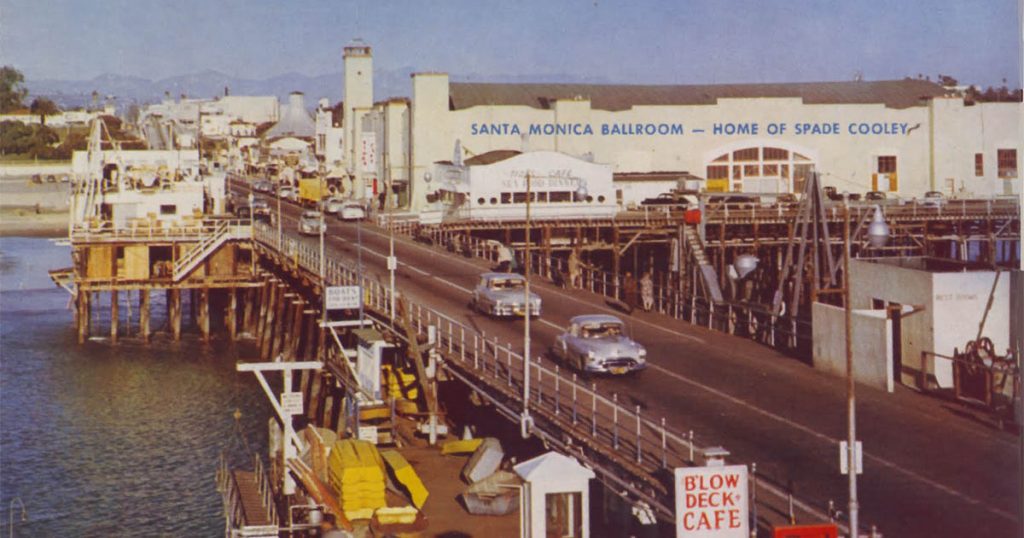

The success of The Texas Playboys is almost certainly what led Spade Cooley to hire Tex Williams in 1943, just after receiving his title of Western Swing’s King. Spade had been sitting in with Jimmy Wakely’s band for a while at this point. They played the Aragon Ballroom at the Venice Pier in Santa Monica on Saturday nights, always bringing out at least a few thousand ticket buyers. When Jimmy landed a movie contract like Roy Rogers, Cooley was asked to take over as band leader. Spade rose to the occasion, hiring new musicians for what he envisioned as a full-fledged Western Swing orchestra and then bringing Tex Williams on board to sing like Tommy Duncan had sang on all those Texas Playboys hits.

While members of the Bob Wills camp and even Wills himself would swear they’d seen the words “Western Swing” used to describe their own Oklahoma concerts years earlier, the fact remains that the earliest uses of the term anyone can find in print are all talking about Spade Cooley’s Western Swing Band. And the second-most cited origin story has Spade Cooley and Bob Wills going head-to-head in an actual battle of the bands at Aragon Ballroom with Spade coming out the winner there to claim the title. Whoever you choose to believe, it seems as though Spade Cooley was the original King of Western Swing.

But it would be easy to believe that Cooley is getting more credit than he deserves. The rest of his career to this point could be viewed as copying Bob Wills and streamlining his product for mass consumption. Where The Texas Playboys leaned a bit more on the “western” part of Western Swing, Cooley had gone around California plucking great players from whatever other genres they happened to play. He’d find jazz up-and-comers from the city, pay $500 a pop to get ‘em in custom cowboy suits, slap some country-sounding nickname on ’em, like Smokey Rogers or Deuce Spriggens (those are real), and throw ’em up on the stage. This led to a tighter, polished sound in Cooley’s brand of Western Swing, a sound that country purists might even call watered down, a Tinseltown facsimile of the real thing.

However you feel about the purity of what he was doing, Spade was raking in serious cash.

Smoke ‘Em if You Got ‘Em

The orchestra was drawing huge crowds everywhere they played, including as many as 8,000 people a night to the Aragon Ballroom during a record-breaking 18-month residency. In fact, Spade Cooley’s Western Swing Band was in such high demand that when someone wanted to hire them for a performance on a date that was already booked, Spade (or his manager) would take the gig, sending in another band that looked and sounded exactly the same. They had three or four of these lookalike, soundalike bands working at the same time.

Spade and Tex

Between 1945 and 1947, the real Spade Cooley charted six Top Ten Singles with Tex Williams on vocals and, this whole time, Spade was still appearing on silver screens around the world. No longer as a stand-in. Spade Cooley’s own name now warranted a place in the credits, usually for non-sequitur musical performances wedged into the middle of Western movies. The hero of whatever-tale-being-told would just so happen to run into his old pal Spade Cooley, who just so happened to have his entire band right there in the bar with him and, the next thing you know, upbeat musical number.

With all this exposure and his being based in Los Angeles, it was really only a matter of time before someone put Cooley front and center in his own TV show and that’s exactly what happened in 1948. The Hoffman Hayride (named for its sponsor) was a completely average variety show. Filmed in front of an audience back at the Aragon Ballroom, Spade would bring on singers, actors, comedians and other celebrities of the day to do their bits. I already told you about that Sinatra appearance. Other guests whose names you may recognize were Dinah Shore, Bob Hope, Tennessee Ernie Ford, Frankie Lane and even Bela Lugosi.

Sounds like a real gas…

But you wouldn’t be able to ask Tex Williams about any of that because he hit the road a year before the TV show. Some people say Tex, the singer on all of Spade’s hits, came around asking for a bigger salary. Cooley refused and Tex quit, taking as many band members with him as he could just to spite Spade. That’s not the story I believe…

The version that looks true to me goes like this: Someone at Capitol Records was paying attention to all the commotion around this Spade Cooley guy. They noticed the person singing all these songs wasn’t getting much attention of his own, so they came around and offered Tex Williams a solo recording contract. Now, we know this is all true so far because Tex Williams’ biggest hit, a song called “Smoke! Smoke! Smoke! (That Cigarette),” came out on Capitol Records in 1947, the year before The Hoffman Hayride went on air. I believe the version of this story that has Tex attempting to turn Capitol’s offer into a good thing for himself, for Spade and for every member of Spade’s outfit. Tex tried to suggest that he could take the contract and continue to sing with Spade Cooley’s orchestra while also hiring them as his backing band for recording sessions and his own concerts, essentially tripling everyone’s paychecks. But that didn’t sit well with Spade’s idea of himself as the head honcho, so he fired Tex Williams and most of the orchestra decided to quit and continue working with Tex rather than Spade.

Of course, none of this stood in the way of The Hoffman Hayride becoming hugely popular on TV, which it was for seven years – until 1955, when Rock & Roll took over the airwaves thanks to artists like Chuck Berry, Bill Haley and Elvis Presley. Spade Cooley was given another TV show after The Hoffman Hayride went off the air but The Spade Cooley Show was also canceled in 1956, after less than a year in existence.

Honestly, Cooley probably didn’t care too much about it. He’s estimated to have amassed a $15 million fortune by the time both shows had gone off-air. (That’s over $120 million in 2017 money, if you’re wondering.)

Having a TV show?

Easy come, easy go.

Even if other kinds of music were more popular, he still had a loyal fanbase out there and he could just go back out to performing concerts if he wanted. So he did, until 1960, when Spade Cooley announced his retirement from music and moved up to his ranch in Mojave to spend time with his family – and, I promise that I’m not making this up – to focus on building a water skiing resort in the California desert.

Now, Spade Cooley was for sure out of his mind (and we’re right around the corner from that part of the story) but building a ski resort with man-made lakes in the desert wasn’t that crazy of an idea at the time. Disneyland had opened its doors to the Anaheim, CA public in 1955. That gave Spade five years to dream up his Water Wonderland. He started buying up property around Mojave and hitting up celebrity friends like Errol Flynn and Clark Gable to become “stockholders” in the company and drum up more publicity for the concept in its developmental stages.

It could have worked.

But it didn’t.

Because I’ve been writing my way around a few missing pieces to this puzzle and it’s finally time to reveal them now.

Meet Spade… Again (And Check Your Sources)

Spade Cooley was arrested for rape in 1945 but acquitted.

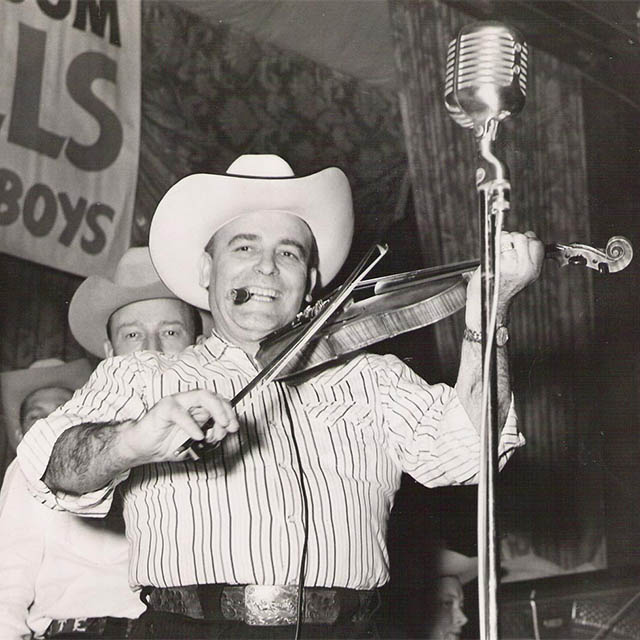

That’s the same year he married his second wife, Ella Mae Evans – whom he’d met three years earlier, while still married to his first wife, Anne. Spade hired Ella Mae as a singer for the band even though everyone you could ask would say her talents were more of the “physical” variety. We have every reason to believe that Spade was cheating on Anne with Ella Mae.

Ella Mae with Spade

In 1946, one year after they were married, Ella Mae was so certain that Spade had been sleeping with other women in their own home, she began packing her things to go to her sister’s place. Spade told Ella Mae that, if she ever left him, he would find her and he would kill her. Their first child, a girl named Melody, was born that year.

Two years after having their second baby, a boy named Donnell, Ella Mae finally did make it out to her sister Elizabeth’s place to escape from Spade. True to his word, Spade tracked her down. He stood in the living room, twisting Ella Mae’s arm behind her back as she screamed, “Don’t let him take me! Don’t let him take me!” over and over. When Elizabeth’s husband tried to intervene, Spade hit him, too.

Everything I just told you is true. But I had to skip over it until now, until we got to a place where we could talk about fact-checking the Spade Cooley story for a second, so I don’t get a bunch of emails from people who don’t see this stuff on Wikipedia.

Sadly, I was not able to gather as many reliable sources as I’d hoped for when researching this story. Typing “Spade Cooley” into Amazon’s book section brings up only three potentially useful results. One book is a collection of trashy tabloid journalism in the vein of Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon, which happens to have a segment on Spade Cooley murdering his second wife. Another book is a novelization of Spade Cooley’s life, which is usually the kind of thing you publish if you’ve got a great story that could get you sued for any number of reasons if you printed it as if it were fact. And the third book is allegedly based on taped interviews with Spade Cooley’s long-time manager, a woman named Bobbi Bennett who is no longer alive.

I do not regard the first two books as reliable sources, for obvious reasons, and haven’t used them for anything in this episode. That leaves Bobbi Bennett as the sole alleged source of information for a couple things I’m going to mention right now, even though I can’t be sure they’re 100% true. But if I had to put money on it, I’d say they’re at least 75% true…

One controversial thing Bobbi allegedly said is that having to clean up the mess after Spade Cooley’s drunken behavior and sexual indiscretions (sometimes with underage girls) was not a rare occurrence over the years. The unpublished manuscript attributed to Bennett states that she paid for ten different women to have Spade Cooley’s abortions in one year alone. That’s a lot of abortions to keep quiet in that era, even by Hollywood standards.

Bennet is also supposed to have written that Cooley’s frequent benefit shows for police departments may have had something to do with the fact that Spade never received so much as a speeding ticket in Southern California. At first, Bobbi’s insinuation seems debunked by that 1945 arrest for rape, which we have court documents to verify. Then again, Spade was acquitted of that rape charge.

And punching Ella Mae’s brother-in-law in his own house while physically assaulting Ella Mae?

Not a problem for Spade Cooley.

Also not a problem when Spade tried to throw a female band member off the Santa Monica pier because she said she was going to have to quit the band. We’ve got multiple eyewitness accounts of that incident. It was even brought up in Spade’s murder trial, years later. And many musicians over the years would tell stories of Spade going on drunken benders, firing half the orchestra, only to hire them back again the next day. This is why I’m inclined to believe that Tex Williams was the good guy.

The ultimate truth is that none of these things that Spade may or may not have done are anywhere near as terrible as what we know he certainly did eventually do to Ella Mae and his daughter Melody at the Mojave ranch home in 1961. So let’s head in that direction…

The Downward Spiral

Once Ella Mae had begun having children, Spade didn’t want her singing with the orchestra any longer. He sent her up to the ranch in Mojave, to raise the kids like a good little housewife while he carried on for years back in the city with work, whiskey and other women.

After retiring and moving up to Mojave full-time himself, Spade’s drinking habit became a much bigger problem. He’d also started mixing the booze with Thorazine, the very first antipsychotic medication created for people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. That drug cocktail sounds worse than it really is but it’s my understanding that alcohol alone can be extremely dangerous for anyone who would have a Thorazine prescription. Just having that prescription means that Spade should probably not have been drinking alcohol at all, let alone consuming many straight whiskeys over the course of his work day and still more in the evenings at home.

With a lot more money going out to the desert water skiing project and not that much coming in for a retired musician plus far fewer opportunities to find distraction in the arms of random women, Spade’s attention turned to Ella Mae in a very dark and abusive way. He seems to have become convinced that Ella Mae was unfaithful to him. Perhaps he started wondering what Ella Mae had been doing with her own time while Spade was fooling around all those years. He’d come home wasted and interrogate his wife. Specifically, Ella Mae had two male friends – Bud Davenport and Luther Jackson. Spade was certain the three of them were having a three-way affair, despite knowing these two men lived together and were all but openly homosexual. When she wouldn’t admit to having the affair, Spade would hit Ella Mae.

In February of 1961, Ella Mae is hospitalized for a nervous breakdown. While in the hospital, she tells nurses that Spade had often hit her over the years but the beatings are growing more severe and Spade has repeatedly threatened to murder her and their children if she tries to leave him. When told that Spade is coming to visit her in the hospital, Ella Mae is positive he’s coming to murder her, right then and right there. She screams that he’s coming to kill her and locks herself in the bathroom of her hospital room until nurses are able to convince her that Mr. Cooley is not around.

Ella Mae has secretly been sending small amounts of money to Davenport and Jackson for safekeeping, in the event that she is able to finally escape the abusive marriage. Even if, by some miracle, Spade decides to give her the divorce she’s at this point begging for, there is no way Spade will be generous with his quickly diminishing fortune.

On March 11, Ella Mae calls Davenport and Jackson from the hospital. She speaks with them on the phone for 45 minutes, of the fear she has for her life and the lives of her children. Spade tries to call her several times during this conversation but the line is busy. When Spade next speaks with Ella Mae, he asks her who she’s been on the phone with for such a long time. He then lies and says he’s had all her calls at the hospital monitored, so he knows exactly who she was talking to and exactly what they were talking about. Ella Mae, presumably taking this to mean that Spade now knows she’s been sending money to her friends to save for her getaway, says, “So what. Now you know.” Spade takes this as a confession of a sexual affair and begins telling anyone who will listen that his wife is cheating on him. He immediately calls two friends for backup and goes over to Davenport and Jackson’s home at 3:oo in the morning to call them homosexuals, lie that he has tape recordings of their phone calls with Ella Mae and punch Davenport in the face. Before leaving, he tells Davenport to move out of California or else Spade will kill him, along with Ella Mae.

On March 15th, Spade finds a receipt in Ella Mae’s purse for a $200 money order. Remember, Ella Mae thinks Spade knows she was sending money to Davenport but Spade had been lying about recording her phone calls. So right here is either where Ella Mae becomes fully gaslighted or else makes a conscious decision to play along with Spade’s version of reality to see if that will put an end to this terrible game. She tells him that she is in love with Bud Davenport and has been sending him money to invest for her. Six days later, on March 21st, Spade files for divorce from Ella Mae on the grounds of extreme cruelty.

But he isn’t done torturing her.

March 23rd: Cooley beats up Ella Mae while waiting for a bank officer to come out to the ranch. When the escrow officer arrives, Ella Mae signs over their real estate property from joint ownership to the sole ownership of Spade Cooley.

March 24th: Cooley calls one of his old violinists to tell her that he will soon be divorced from his cheating wife and has every intention of asking for her hand in marriage. She thinks he is literally joking and says, “Okay.” Then, a few days, later Spade calls back to tell her the exact date they will be married and to put his 14 year old daughter, Melody, on the phone to say she is looking forward to having a new mother. In the following days, Spade will call various people and put Ella Mae on the phone to confess her romantic affairs. If she refuses, Spade will beat her and threaten to kill her. Spade forces Ella Mae to tell their daughter, Melody, that Ella Mae is a “slut” and a “whore” and that she’s been hooking up with other men in trailer parks and motel rooms. At one point, Spade kicks Ella Mae in the stomach and tells Melody, “She only cries when you hit her. She doesn’t care what’s happening.”

March 29th: Spade tells a business associate living in a trailer on the ranch property to move his trailer a mile down the road.

March 30th: Ella Mae calls her sister to say that she’s in bad shape and desperately needs a place to hide from Spade. Her sister tells her to wait for a call from some people who can help her. This is the last time they’ll speak to each other.

March 31st: Ella Mae has to see a nurse after jumping from a moving automobile to get away from Spade beating and choking her while he is driving the car. It is the third or fourth time she’s jumped from a moving car that year and she has injuries consistent with such an event – bruises on her back, tailbone and ankles – but also, a black eye.

Even if you’ve made it this far, I’ve got to tell you – this is about to get so much worse. If you’re at all worried about what you might read here then, I promise you, it is that bad and you should skip the entire next section. Scroll past the bold header beneath this and keep scrolling until you see the next bold header, which will be beneath a Soundcloud widget.

This isn’t fun to read and it’s difficult for me to write. But I feel like it’s important to know exactly what happened, here, because the way this story ends was very nearly a lot more upsetting than it is now.

April 3, 1961: Murder in Mojave

On April 3rd, that business associate of Spade’s living in a trailer on the ranch, Jarrold Enfield, stopped by the Cooley house. Spade told Jarrold that he finally had concrete evidence of his wife’s infidelity and he brought out a written confession from Ella Mae.

Jarrold looked at the confession and said, “Yes. It’s Ella Mae’s handwriting, Spade. But I know how you got it.”

‘What difference does it make?’ Spade replied.

Around 2pm, a couple other business partners showed up to handle some financial matters – signing payroll checks, things like that. He asked one of the guys to go buy a bottle of whiskey and bring it back to the house so they could all have a drink together. That’s what happened.

At 4:00pm, Melody calls from a nearby friend’s house to ask if she and her little brother could spend the night there. Spade said they could. 40 minutes later, a third business associate shows up at the ranch. There are now four men on the scene and they quickly become involved in an argument over the proper way to handle a mundane payroll matter. Spade shoves a guy, challenges him to a fight and then kicks him out of the house when he won’t fight. Then, he starts trying to talk the two remaining men into going with him to fight Bud Davenport and Luther Jackson. Both men decline. One of them leaves.

It’s now just Spade Cooley and L.C. Martin in the room when Ella Mae walks in and sits down. Martin would later recall that her skin looked pale and she had a black eye. There were no other visible bruises or cuts on her face or body. She did not appear to be missing any hair from her head.

Spade kept trying to convince Martin that they should go beat up Davenport and Jackson. Martin finally grew tired of this and left at 5:45pm.

Fifteen minutes later, Ella Mae called the house where Melody was at to ask her to come home, so Ella Mae could explain to her “what this was all about.” Melody said she’d rather not come home. At 14 years old, there’s no doubt that Melody was quite aware of the abuse her mother was taking and she was surely terrified of her father by this time. When Melody said she didn’t want to come home, Spade got on the line to say he understood – Melody didn’t want to come see her mother, did she? Melody told her dad, yes, she would like to see her mom. Spade said she’d better come on home, then.

When Melody got off the phone, she gave herself some insurance. She asked her friend’s mother, a Mrs. McWhorter, if she could drive her back to the Cooley Ranch, drive away and come back twenty minutes later to pick her up again.

Between the time that L.C. Martin left the home and the time that Melody arrived, Ella Mae Cooley sustained the following injuries at the hands of Spade Cooley, not counting the injuries he’d already given her: her lips were split open; the skin of her chin was cracked and bleeding; her neck, nose, shoulder, chest, hip, arms, wrist and legs all suffered deep bruising and/or broken bones or cartilage; the nipple of her left breast was burnt black and partially separated from the breast; she was missing a clump of hair from her head and wounds found in her vaginal and rectal tissues were consistent with a bloody, mucous deposit that extended five or six inches down the end of a broom handle.

When Melody walked in the house, she heard her father telling someone on the phone not to call the police. The furniture in the living room showed signs of a struggle. There were bloodstains on the floor and there was blood and hair in a broken drinking glass on the table, next to a bottle of whiskey. Melody asked if the police were coming. Spade told her yes, there would be some there in a minute, it would all be over in a minute. Then he told Melody to follow him because he wanted her to see her mother…

They walked into the bedroom. There were more bloodstains on the carpet in the bedroom. Blood on the sheets of the bed, blood on a rifle in the bedroom. Blood on an ashtray stand, blood on the walls and blood on her father’s pants. Melody did not see her mother in the bedroom.

Spade walked over to the bathroom area and said, “Get up Ella Mae. Melody’s here.”

No response.

Spade then dragged Ella Mae’s naked body out of the shower by her hair and slammed her head into the floor, twice. Ella Mae did not react to this with any sound or physical response. She was not dead yet but she had massive internal injuries and hemorrhaging.

Spade informed his fourteen-year-old daughter that she had three minutes to get her mother off the floor or she would have to watch him kill her. Then, he went into the living room to yell out a countdown: “One minute left! Half a minute left, Melody! Time’s up, Melody!”

Of course, Melody couldn’t get Ella Mae to wake up. Spade came back in the bedroom and sat Melody in a chair. He said, “Alright, Melody, you’re going to watch me kill her.” Then, he stomped on Ella Mae’s stomach three times with his boot, which medical examiners would later conclude is what finally caused Ella Mae to die twenty minutes after this.

Spade knelt down near Ella Mae and said, “We’ll just see if you’re dead, slut,” and he burned each of her breasts with the tip of his lit cigarette.

No response from Ella Mae.

Melody tried to run from the room but Spade grabbed her. “Alright. I’ll give you two more minutes to get her off the floor-” but the phone rang and Spade went to answer it. When he was done with the call, he came back in the bedroom and told Melody to come out to the living room, he wouldn’t touch Ella Mae any more.

In the living room, Spade had his teenage daughter sit on his lap so he could put his hand on her breast and kiss her in a very non-fatherly way. Spade told Melody that he was going to turn all of his love over to her and to her little brother because Ella Mae had crushed him.

Obviously trying to think of anything in the world to get away from this horror, Melody suggested that she go turn off the shower, which had been running the entire time. Spade seemed to think that sounded like a good idea and told her to pour some water on Ella Mae while she was in there and see if that would wake her up. Melody poured the water on her mother’s chest because the rattling sound coming from Ella Mae’s throat made Melody worry that her mother might drown if she poured the water on her face.

Melody returned to the living room. The phone rang again. It was the private investigator Spade had hired to confirm the details of his wife’s so-called confession. The private eye explained that Ella Mae’s story wasn’t adding up. She appeared to never have stayed at the motels she said were used for the affairs Spade made her invent. While he talked on the phone, Melody kept an eye out the window, expecting and hoping for Mrs. McWhorter to be coming back. When Spade hung up, Melody told him she thought she saw Mrs. McWhorter coming and she’d better go meet her outside to keep her from coming in the house and seeing what was happening. She managed to kiss her father on the cheek to keep up appearances before bolting out the front door. She heard Spade call after her not to tell the police anything or he might have to kill her too.

Outside, Melody hid behind a trailer until Mrs. McWhorter really did arrive and, then, Melody ran across the field to meet her vehicle a safe distance from the house.

Spade cleaned up some of the blood before his manager, Bobbi Bennet, came by for an already scheduled meeting to talk business. In the middle of their meeting, Spade went into the bedroom to look at Ella Mae’s body. He came back to the living room and told Bobbi that Ella Mae was hurt. Bobbi said they should probably call a doctor, if that was the case, and Spade said no. So they called a friend in Los Angeles who was a nurse. That call was at 9pm. Upon being told that there was an accident and she should come out to the ranch, this nurse recommended they go ahead and call an ambulance if it was that serious but she would head there as soon as she could. Of course, no ambulance was called and, when their L.A. nurse arrived at 11pm, she checked Ella’s pulse to find that she was finally, and probably mercifully, dead.

The nurse called a local hospital and, then, the sheriff’s department, trying to get an ambulance out to the ranch. A deputy sheriff was told about “a dead body” and an ambulance arrived at 11:35pm. Spade helped the ambulance driver load Ella Mae’s corpse onto a gurney and rode in the back of the ambulance with her to the hospital. By 3am, Spade was in a room at the sheriff’s department giving an official statement. He’d changed out of his bloody clothes and was wearing one of his Western stage suits as he calmly lied and told the police that his wife had simply fallen in the shower after burning her own flesh with a cigarette to prove that she loved him.

DETECTIVE: Alright, then, after your daughter, Melody, left – Mr. Cooley, you and your wife continued having trouble. Is that correct?

SPADE: We didn’t. We had some trouble but most of it was conversation at that point.

DETECTIVE: At that point…

SPADE: She said- When she told me this, she said to me, “You don’t think I love you? Let me show you.” And I had a cigarette in my hand and she took it and burned both of her breasts briefly. I don’t know how bad but she just touched them.

DETECTIVE: With a…?

SPADE: With a lighted cigarette. “Does this prove how much I love you?” she said.

DETECTIVE: And that was where in your house?

SPADE: Still in my bedroom. Our bedroom.

DETECTIVE: Is that right?

SPADE: Mm-hmm.

DETECTIVE: And it was just you and your wife there?

SPADE: [talking at same time] We call it the den but it’s the largest room.

DETECTIVE: Was she clothed at that time?

SPADE: No, she wasn’t. She had a blouse on that she pulled open.

DETECTIVE: I see. Then what transpired after the burning?

SPADE: She went to the shower.

DETECTIVE: And…

SPADE: She staggered when she walked because she was weak. She had not eaten, as I told you, for days. She got to the shower and she slipped on the floor. The door opened when she opened the door and I heard her head hit a glass container or something in there. I never did look to see what was broken but she had landed flat on her face and there was quite a crack. I would say to you that I believe that the autopsy will prove that she did die of a concussion.

The entire recording of this one hour conversation can be heard here but I can’t say I recommend listening to it.

The Trial of Spade Cooley

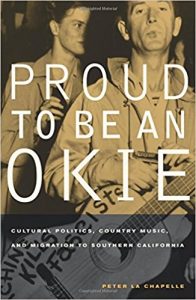

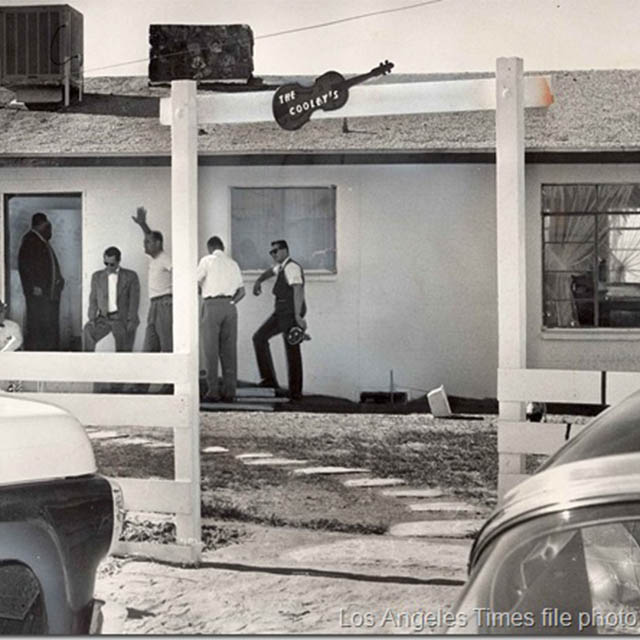

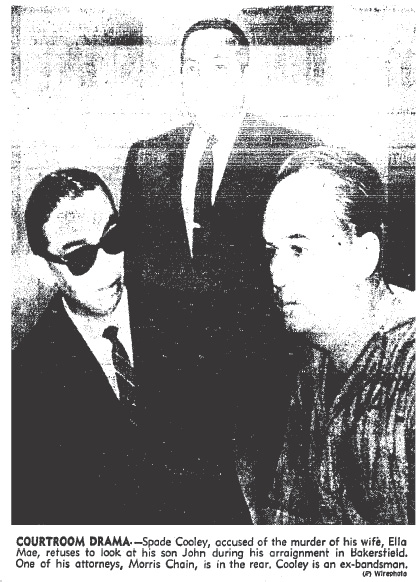

Following the interview and a search of the Cooley ranch home, Spade Cooley was arrested on suspicion of murder and taken to the Bakersfield county jail. [Would actually be the Kern County Jail located in Bakersfield but I misspoke in the episode.]

Detectives at Cooley home on April 5, 1961

The forensic evidence against Cooley was overwhelming but his trial was not an open and shut case. It lasted a month and the media circus in the courtroom has since been compared to coverage of the OJ Simpson trial, many years later. You’ve got to remember just how famous Spade Cooley was. A mere ten years earlier, he was at the peak of his fame. If any of the jurors were younger than 30 years old then they very likely grew up watching Spade on TV. Imagine if Mr. Rogers or Spongebob Squarepants were somehow being tried for murder and you might get some idea of what this was like at the time.

Probably, most people did not want to think that Spade Cooley was guilty of this awful crime. We’re told that Spade was given the run of the jail throughout the trial, permitted to walk freely out of his cell, taking his meals with the guards in their separate dining room where the food was much better. But Cooley’s celebrity was no match for the horrific testimony of his teenage daughter. Even with all the scientific evidence pointing to Spade’s guilt, fans could have made themselves believe a random psychopath had visited the Cooley ranch that night or maybe even that Spade was being framed. Melody Cooley took those options off the table when she gave her memories of what Spade did to Ella Mae that night and everything else he did to her in the days, weeks, months and even years leading up to that night. And Spade had a heart attack, right there in the courtroom.

Spade Cooley was found guilty of first degree murder. Many members of the jury were crying as the verdict was read. Spade had plead not guilty by insanity from the beginning of the trial but withdrew the insanity plea – after the jury found him guilty, before proceedings could begin to determine the state of Cooley’s psychological health. A private investigator hired by Spade’s own defense team would later disclose that Spade Cooley had given private testimony that experts would analyze to say Spade was, himself, a closeted homosexual. If this is true, we can guess Cooley didn’t want that information to be made public, although it would, perhaps, shine a little light for us on his hated towards Bud Jackson and Luther Davenport, who were confirmed to be lovers during the trial. Spade may have been jealous of their ability to accept their own sexuality and be open about it. When Spade had taken the stand to give his own rambling testimony, much of it had centered on the free love sex cult he believed his wife was starting with the two men.

Spade Cooley at his arraignment

After withdrawing the insanity plea, Cooley also waived his right to have a jury decide his sentence. The trial judge sentenced him to life in prison but the story doesn’t end there.

Most convicted murderers in his position would have been sent to San Quentin – not a nice place to be, to say the least. But Spade’s poor health saw him placed at the state prison in Vacaville.

Cooley seems to have mellowed out in prison.Spade built fiddles in the prison hobby shop and taught other prisoners how to play music with them. He reportedly found religion and showed remorse for his crimes, even going so far as to say that if he was ever released then he’d like to become a preacher like Billy Graham.

Five years in to Cooley’s life sentence, Ronald Reagan was elected governor of California. The petitions for Reagan to grant Spade Cooley a full pardon for his crimes came pretty much immediately. That was a little bit much for Reagan but he would recommend, in 1969, that Spade Cooley be granted parole and released from prison. The parole board unanimously voted to approve that recommendation with Spade scheduled to be released the following year, in 1970, having served only 8 years of a life sentence.

With a few months remaining before his release, Spade was taken on a little field trip to perform at a police benefit concert, just like the good old days. Before an audience of roughly 3,000 people, Spade played wonderfully and was given a warm reception from the crowd. Backstage, in his dressing room, during an intermission break, Spade was visiting with some friends who’d come to see him. He expressed surprise and wonder that people seemed ready to accept him back. He even said, “I have a feeling that today is the first day of the rest of my life.”

Those were Spade Cooley’s last words, as he suffered another heart attack and died just after speaking that sentence. What Spade didn’t know was, when he returned to the stage after the break, they were planning to surprise him with the news that Ronald Reagan had decided to give him a full pardon, after all. As if the torture and murder of Ella Mae Cooley had never happened. As if Ella Mae Cooley had never been born. As if Ella Mae Cooley had never lived. As if she’d never died at the hands of Spade Cooley.

Six months later, the building that had once been the Aragon Ballroom on the Santa Monica Pier, where Spade Cooley’s fame and fortune began to rise, burned to the ground and was never rebuilt.

Thank you for reading (and listening to) Cocaine & Rhinestones. Every episode of the podcast is written and produced by me, Tyler Mahan Coe. If you have questions about anything here or anything else, you can send me an email at questions@cocaineandrhinestones.com – your question may be used in a Q&A episode at the end of the first season. BONUS: Cocaine & Rhinestones Season 1 Q&A Episode!

Next week’s episode, I’ll be talking about the wonderful and mysterious Bobbie Gentry. You know Bobbie from “Ode to Billie Joe,” “Fancy” and, not much else, because she disappeared completely in the early ’80s. Her whole story is amazing and I’m really proud of the episode, so I hope you’re subscribed to the podcast for that.

If you have an account on iTunes or Stitcher or any other big podcast directories like that, I would love for you to find Cocaine & Rhinestones there and leave me a good review. As always, I’ll ask that you share the episode with just one person. You must know one person who might like it and if they read or hear it then you’ll have someone to talk to about this horrific thing you both know!

-TMC

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [linked, if available]:

- The Louvin Brothers – “The Knoxville Girl” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Spade Cooley – “South” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Spade Cooley – “Swingin’ the Devil’s Dream” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Spade Cooley – “Miss Molly” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bob Wills & The Texas Playboys – “Take Me Back to Tulsa” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Spade Cooley – “Detour” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tex Williams – “Smoke! Smoke! Smoke! (That Cigarette)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Spade Cooley – “Crazy ‘Cause I Love You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Excerpted Video

The following videos were either discussed, excerpted or used as a source in this episode. It’s possible that they may have been removed for any of a number of reasons since this post was written:

Commentary and Remaining Sources

Researching this episode was a complete nightmare. Every step took it further away from being a dark little piece of trivia and, by the time I got to the court papers with all the details of Ella Mae’s injuries, this murder was fully alive in my mind. I could see it all happening. It was terrible and real. If this is how deep into it those true crime murder podcasts get every episode, I have no idea how they do it. Maybe some of them will do this story after hearing it on this podcast. I’m pretty certain Spade Cooley is the only convicted murderer with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, so that’s something.

I did really enjoy looking into the history of “Knoxville Girl.” I guess that murder is far enough into the past that they didn’t record a play-by-play of the gruesome injuries and that helps it remain a little more cartoonish for me, maybe. I know Charlie Louvin has said the line about the Knoxville Girl’s “dark and roving eyes” is a hint that the narrator of the song murdered the girl because she was unfaithful. You definitely don’t have to email me about that.

It would be fun to do more murder ballad intros, I think. There are a few more murders in country music that I know about but maybe it would be cool to do a whole episode on the true stories that inspired all the murder ballads. I’ve got most of the 2nd and 3rd seasons planned out already but that could possibly fit in to season 4.

It’s interesting how much of this story could be told about so many other people in the entertainment industry minus the murder at the end. You know, all the behavior we write off as the “eccentric price you pay” for artistic greatness. Sorta makes you wonder where the line is… or if it’s even there.

For what it’s worth, I think the Spade Cooley story throws an interesting wrench into the conversation about treating an artist and their art as two separate things. Should you separate art from artist? Should you not? Should you feel bad for enjoying Spade Cooley’s music? I cannot tell you what to think about that but here’s something to consider. If you do want to say that nobody should listen to, or enjoy, and certainly should not purchase, Spade Cooley’s music because of the suffering he caused in this world, well… Assuming they’re still alive, the people in this world who suffered the most because of Spade Cooley are his children. At no point in my research did I come across anything suggesting that Spade Cooley sold or lost the publishing on his music. If he had a will and his affairs were in order, which they probably were, then his children probably inherited the publishing. I’m making assumptions here but all I’m assuming is that things went the route they typically do go. And if that is the way they went here then it would mean the actual, living victims of Spade Cooley directly benefit from the sales of his music.

Kind of a weird catch 22, there, huh?

Dennis Quaid bought the rights to all the Cooley kid’s stories around 2005 but that movie doesn’t appear to be happening. And I don’t know why. I did look to see if any of the children ever gave interviews or anything to suggest they’re open to talking about this. I found nothing.

There are actually quite a few things that may be true about Spade’s personality that I left out of the episode. I really tried to stick with only saying things that come from multiple sources but a couple things that seem probably true to me are…

He liked to gamble a lot and his nickname is supposed to have come from a really good night of poker for him involving the suit of spades. Maybe drawing three straight flushes in the suit or something like that. It’s one of those stories that gets more unbelievable each time it gets told, so I really couldn’t choose one version of it. I think I saw someone say that he drew three straight flushes in spades in a row, which is, you know, not very likely.

Also, Spade may have been a big practical joker. I can’t remember where I read this but the story goes that one time he got a friend of his hired to play at a bar, only when the friend showed up it turned out the gig was in the men’s room. It didn’t seem to fit in the story. I wasn’t making him a jerk or anything for the beginning of the episode but that really just seemed to make him more likable or something. Like I said, I’ve never done this before so I didn’t know if that would come off as dishonest, if I led you to believe that he was this likable guy, which by all accounts he was… If I made him seem like someone you could be friends with, I don’t know. I didn’t want it to come off as manipulative.

Listening back to the episode I noticed that the way I keep using the word “homosexual” may sound weird. That’s the exact wording that was used across the board in the court documents and I figured I’d better play it safe by sticking to the source. I really didn’t want to get in any actual trouble. I’m not too worried about social trouble but actual trouble. In this entire episode, I tried to be extremely careful about my sources on this one.

Some tabloids grabbed on to a story that Ella Mae had an affair with Roy Rogers. That does not seem likely. If I recall correctly, Ella Mae said that while she was hospitalized and Spade had already been “interrogating” her between beatings about the affair he “knew” she’d had with Roy, etc. We know that Ella Mae invented things that she thought Spade wanted to hear, so I don’t see any reason to treat that as any different than what we know for a fact happened.

Local Bakersfield paper with Spade Cooley’s deranged testimony.

That’s it.