The Louvin Brothers are widely regarded as the most influential harmony duo to ever cut a country song. The way Charlie and Ira could sing together is downright otherworldly. There’s even a special term we had to invent for family (it’s always/only family) who can sing this way: blood harmony. That being said, it’s possible we’ve never heard what they could really do.

By the way, do you believe in evil?

This episode delves in to exactly what blood harmony is and how the magic of it can’t save you from beating the living hell out of each other at every opportunity. Here is the story of two dirt-poor brothers who fought for fifteen years to achieve their lifelong dream and what happened after that. (Hint: it involves whiskey and bullets.)

This episode is recommended for fans of: singing, physics, the Radiolab podcast, mandolins and Roy Acuff.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

In addition to The Library, these books were used for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

Sympathetic Resonance

Picture an ocean wave, a big whitecap. Now, zoom in real close on the top of your wave and you’ll notice a mist hovering right above it, traveling with the wave. If you were trying to capture the perfect image of this wave, you could Photoshop that mist out of the picture. It’s just visual noise.

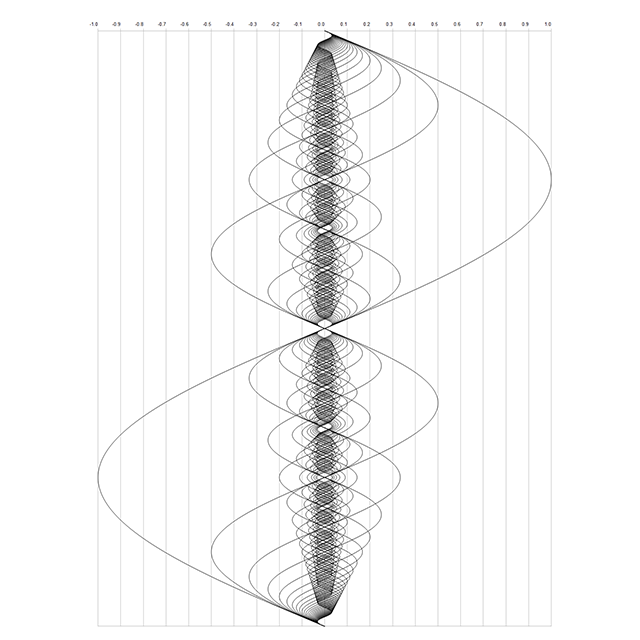

Every sound you’ve ever heard in your life is a wave. Sound waves have that mist above them, too. We call them overtones. Picking a string on your acoustic guitar doesn’t produce a perfect tone of the note you want to hear. Your guitar string mainly produces that tone but you get some overtones in the deal as well. Playing a bunch of different tones together in a chord gives you even more overtones, all splashing into each other. This is especially noticeable on acoustic guitars because of the way they’re built to project sound by allowing it to resonate in the body of the instrument.

The human voice functions in a very similar manner. Your chest, mouth and nasal cavity are three of the seven resonators your body uses to create vocal sounds. An acoustic guitar generates a lot of overtones with one resonating chamber and the human body has seven. This is how we end up with a thing called throat singing. It’s been happening in Mongolia for a very long time. The singer creates a tone in their throat and exaggerates the overtones by manipulating the muscles in their throat and mouth. It’s like a magic trick except knowing how it’s done doesn’t make it any less amazing.

You may be wondering why a podcast about country music is starting off by talking about Mongolian throat singing. Well, in the 1920s, this guy from Texas, named Arthur Miles, randomly started doing it. We have no reason to believe that Arthur Miles was even aware of Mongolia’s existence. It’s quite possible that he thought he invented throat singing.

On one side of the planet, you’ve got a culture singing in an extremely peculiar way for hundreds, maybe thousands of years. One day, a guy on the other side of the planet starts singing that way, too. That’s why we’re talking about throat singing and overtones. Because, if it can happen once at such a great distance, then you’d expect it to happen more often at close proximity, wouldn’t you?

It does.

The Harmonic Series

Going back to the acoustic guitar for a second, you don’t have to play a string for it to create overtones. All you have to do is play any string. If one of the strings you did not play has the potential to create any of the overtones in the string you did play, the unplayed string will begin sounding that overtone all on its own. I’ll say it another way: if two guitar strings share an overtone then you only need to play one of the guitar strings for the other guitar string to start making that sound without anyone touching it. This is called sympathetic resonance. It needs help to get started but every guitar wants to sing harmony with itself.

You can not talk about harmony in country music without talking about The Louvin Brothers. Often cited as the most influential harmony duo to ever cut a country album, they recorded together for only about ten years. The music is exceptional and the legend is huge but, make no mistake, this is a cautionary tale.

The Louvins have one of the most mismanaged careers I’ve ever come across with a strong thread of bloodshed and addiction running through the entire thing. All they ever wanted was to make one dream come true. It takes 15 years, maybe a dozen false starts, three record deals, two wars and, at least, one attempted murder – and they get there.

Some would call it a battle between good and evil. I guess that depends on whether or not you believe in the Devil…

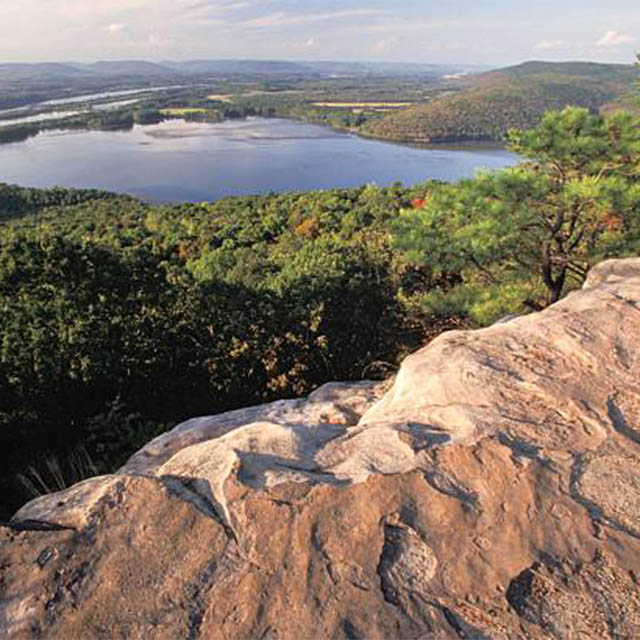

Sand Mountain

Colonel Loudermilk grew cotton on Sand Mountain in Alabama. Growing cotton on a hilly plateau isn’t something you’d normally do but you’d do it if it was the only choice you had to feed your wife and seven children. At least two of Colonel’s kids figured he must be a pretty dumb guy to end up with the kind of life he had.

Charlie Loudermilk and his big brother, Ira, hated every day of picking cotton except one. That was the day Colonel Loudermilk took the three oldest kids out to the field, right at sunup, and showed them all a $5 bill. He said whoever picked the most cotton that day would get to have the money. $5 might as well have been $500 to these kids; they hit the cotton rows at top speed. They’d have spent the entire day in the field anyway but the idea of that $5 bill had them too busy to think about the aches and pains of picking cotton as fast as they could. At the end of the day, Charlie had picked the most. He was shorter than the other two, an advantage when it comes to picking cotton. Charlie got the money and then all the kids got a lesson in how dumb their father wasn’t. Colonel said, now that he knew how much cotton they could pick in a day with the proper motivation, they’d better pick that much every day or they’d get a different type of motivation come sunset.

Sand Mountain

Don’t get the idea that Colonel was a wicked man. This isn’t a Charles Dickens novel. He didn’t beat his wife. He didn’t drink alcohol. You’d have a hard time finding a farmer in 1930s America who didn’t whip his kids when he thought they deserved it. The whole family had to work that cotton field and others in the area so they could survive. It was brutal labor – the kind we have laws against forcing young children into today. In the 1930s, you worked that field or you took a beating. Colonel’s daughters were exempt from physical punishment and they ran off and got married as soon as they could in order to escape the work, two at 15 years old and one at 13. Of course, they just ended up working in their husbands’ fields instead of their father’s fields. Still, the way Charlie tells it in his autobiography, Colonel could go from zero-to-whip-your-ass in ten seconds flat. The oldest boy, Ira, he took the worst of it because whatever dumb thing the boys did was almost always Ira’s idea that he’d talked Charlie into going along with.

Ira could talk Charlie into anything. Like the time with the persimmon tree…

Some species of persimmon tree bear a delicious fruit – only, you’ve got to wait until it gets ripe before you eat it, almost ripe enough to fall off the tree on its own. If you eat the fruit before it’s fully ripe, it tastes awful and your body can’t digest it, so you’ll get sick too. The Loudermilks had one of these persimmon trees growing on their property. Just one. When you’re that poor, every bit of food you can grow for yourself counts.

One year, Ira decided he couldn’t wait any longer for the persimmons to get ripe. He sent Charlie up to the house for an ax and chopped about halfway through that six-inch tree trunk, enough so they could bend the tree over to get at the persimmons. They propped the tree back upright with a small post and ran off to eat the bitter, unripe persimmons and make themselves sick.

Please, understand that these boys 100% knew they’d catch a beating for killing that persimmon tree and they knew they’d kill the tree by cutting halfway into the trunk. When Colonel was simply punishing them for something they knew was wrong when they did it, he’d go out and cut a switch from a hickory tree for the job. That’s what Charlie and Ira thought they were signing up for with the tree.

Well, the day after the boys’ covert operation, Colonel happened to walk by the persimmon tree. He noticed that little post propped against the tree and, not knowing what it was or why it was there, he kicked it away and the entire tree fell down on top of him. You may think that’s funny and I definitely do, too. Colonel did not think it was funny. Not even a little bit.

He was bruised and bleeding when he got home and he beat Ira with the same post they’d used to prop the tree back up. Beat him until Ira lost consciousness. And his mother had to intervene to stop the beating at that point. Their oldest sister was sent for a doctor. It took Ira “a day or so” to recover.

In his book, Charlie spends the next 14 paragraphs, nearly the rest of this chapter, explaining Colonel’s upbringing: how Colonel grew up forced by his drinker of a father to make charcoal, which sounds like it’s maybe twenty times worse than picking cotton, the way Charlie tells it. He shows us little Colonel, down there in a fire pit while grandpa Loudermilk drunkenly swears at his children to work harder. Charlie points out that his father must have felt like he was literally working in Hell.

Take a Pebble and Teach It to Grow

Satan Is Real is the name of Charlie’s autobiography. I’ll be using it as one source for this episode and I’ll be telling some of his stories but listening to (or reading) this episode of Cocaine & Rhinestones is not a substitute for reading Satan Is Real. There are so many great things in the book that I won’t have time to talk about and I’m skipping over a lot. Of course, it’s published under the name Charlie Louvin, which I’ll get to, but it’s essential reading for every fan of country music. You can run it down the checklist of everything a country artist’s autobiography should be. There are dated stories and attitudes virtually guaranteed to make modern readers uncomfortable. Charlie’s established as an unreliable narrator about halfway through the book, so you’ve got more than a few real crazy behind-the-scenes tales that could be total bullshit. Wannabe musicians can learn a lot about what not to do from these pages. And one thing I think it does, perhaps better than any other book, is illustrate the effect that a show like the Grand Ole Opry could have on people living in poor areas of surrounding states.

These two brothers spent days with their mother, Georgie, when they were still too young to work in the cotton fields. The boys helped her with chores around the house, as she taught them to sing songs her ancestors brought over from England – songs that were passed down through generations. Charlie remembers it as feeling like they were singing with ghosts during these early lessons. Many of these songs would later end up on Louvin Brothers records.

There’s a thing called “blood harmony,” which is a term for how freakishly well some close family members are able to sing with each other, especially when they were born around the same time. Listen to The Louvin Brothers’ “When I Stop Dreaming.” Okay, that’s Ira singing the verse. Charlie comes in on the chorus but he’s singing in the vocal range where Ira just was – it’s not Charlie doing the high part. Ira goes up to sing harmony over the part casual listeners often think is still him. If that doesn’t blow your mind, it’s because you live in a world where The Louvin Brothers probably invented this 80 years ago.

It’s not just the genetic similarities, which I’m sure do help. It’s the knowledge of the other person’s voice. Like how kids from the same family mispronounce words exactly the same way? Except nobody ever tells family who can sing blood harmony that they’re doing it wrong and blood harmony only gets better. The understanding of the other person’s voice keeps growing stronger and stronger over time – until you know so completely what it can or can’t, will or won’t do that you can sync your voices together, as if the other voice were an extension of your own. Ira is approximately three-and-a-half years older than Charlie. That age difference is the only time when Ira didn’t know the sounds his brother’s mouth made. Charlie has never known a time without the sound of his older brother’s voice.

When the boys were good enough, Georgie had them sing for their father. He liked what he heard. He liked it a lot. Believe it or not, Colonel was a big fan of music. He played a banjo in the evenings and would occasionally get a bunch of people to bring instruments out to the house to sing songs for each other. When it turned out his boys could sing, he was proud. He wanted to show them off to visitors but the boys were too shy to sing for other people. They had to hide under the bed and sing from there for a while. Never getting any negative reviews, they eventually came out from under the bed. It got to the point where Colonel would make them sing for strangers when they were out in public.

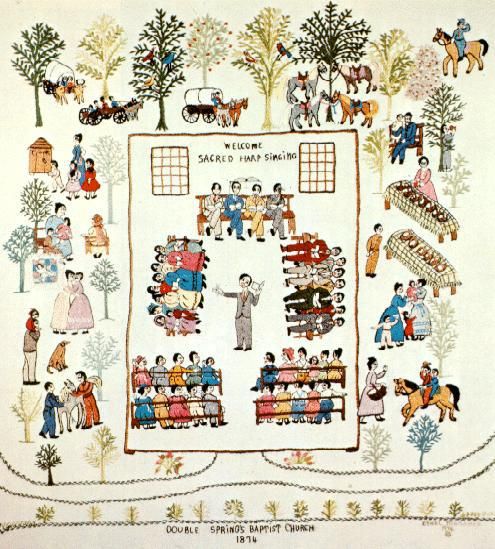

He trained them this way because part of their mother’s annual family reunion involved singing hymns in a special style of singing known as Sacred Harp. There were no harps involved. There were no musical instruments involved. Nothing but voices in a room, organized by their vocal range, everyone facing towards the center, watching the family leading the current song. That’s the Sacred Harp. Charlie and Ira were being groomed to go into the middle and lead the Sacred Harp with their mother. Colonel didn’t sing in public.

Sacred Harp

Charlie says there’s nothing in the world like hearing Sacred Harp singing. He also says it can’t be recorded with a microphone. I believe him.

The very first time the brothers go into the middle to lead a song at Sacred Harp, a girl in the family who leads the song after theirs keeps doing this thing where she sends the pitch of her voice way higher than what everyone else is doing, sings her part up there for a while and then lets her voice fall back down to sing with the rest of them. Ira pays very close attention to her and begins practicing the technique when singing with Charlie.

You’re Learning

By 1940, the boys are hooked on the Grand Ole Opry. Charlie’s 13 and Ira is 16. Every Saturday night, as soon as they get done eating dinner after work, they run to their neighbor’s house to listen to the radio. About 50 people come to this house on Saturday nights – because they have a radio. You can fit 25 people in the living room and another 25 outside on the porch. When your favorite singer is on, you go in to listen, then you come back outside so people who like the next singer best can go inside to hear.

The Loudermilk boys’ favorite singer is Roy Acuff and, one Saturday night, Roy says he’s got a show coming up at the gym of a nearby school. The day of the concert, Charlie and Ira go down there and hang around outside with everyone else too poor to buy a ticket. They can hear the show from out there and see some of it through a window. On the walk home, the brothers decide they’re gonna have to sing on the Grand Ole Opry someday because some of the songs Roy Acuff played that night sound a little better when they do ‘em.

Over the next few years, they’ll play anywhere in the area that will have them. They’re not making any money. Just doing it for practice with a boy from the area who has a guitar. After saving up to get their own instruments (guitar for Charlie and mandolin for Ira), they get a gig at a small carnival that pays them each $50 for the day. There’s no turning back now.

Ira leaves home to work at a cotton mill in Chattanooga, TN, coming back to the farm on weekends to keep playing small shows with Charlie. They enter a Chattanooga radio station contest with the prize of a 15 minute radio show – at 4:30 in the morning. They win, with some help from a murder ballad Georgie taught them, “Knoxville Girl.” (You can read more about “Knoxville Girl” in the intro to Spade Cooley’s episode of Cocaine & Rhinestones, before it gets into the really bad stuff.) Charlie and Ira convince their dad to let Charlie move to TN with Ira, so they can do the radio show. That leads to their second paying gig – $100 each, double what they made the first time.

This is where they should have found a manager because, even though they move up to a bigger radio station in town, the outside gigs start paying way less. They’re doing pool halls where the pay is so bad they clear empty beer bottles from tables between sets for some extra money in their paycheck. It’s good practice performing, though.

Charlie ends up having to enlist in 1945. Once he turns 18, he can’t get a day job. Everywhere he applies, they won’t hire him, since he’ll be drafted for the war by the time they train him for work. Charlie joins the Air Force. Ira had already been drafted and quickly discharged when his back was injured in basic training. When Charlie returns after 14 months in the Air Force, he and Ira decide to shorten their last name from “Loudermilk” to “Louvin.” They’ve noticed some people have trouble saying or remembering the name Loudermilk. Besides, maybe they’ll have better luck with a new last name…

Running Wild

The Louvin Brothers get another radio show. This time, it’s in Knoxville, TN and the show is a gospel format. They’re making such little money that an offer of $20 a week to host a different radio show in Memphis is enough for them to move away from Knoxville. That $20 a week offer comes from a man named Smilin’ Eddie Hill. He has a station in Memphis ready to buy a package radio show but he promised a great singing duo without really having one. Eddie’s that kinda guy. Overconfident, you might say. A hustler.

Living in Memphis makes it easier to travel farther for the small money shows that come from working on a radio program. They take everything they can get. Charlie starts using uppers to get all the driving done. No big deal.

It’s while working out of Memphis that Ira quickly builds an impressive catalog of original material. He’s written maybe 30 songs at this point and they’re having no luck getting them to publishing companies. Eddie Hill finds out about this and offers to take their song over to Acuff-Rose in Nashville. That’s “Acuff” as in Roy Acuff, The Louvin Brothers’ favorite singer from the Grand Ole Opry, and Fred Rose, who had written “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” among other legendary hits. This is not a publishing company. This is the publishing company and Fred Rose loves their material. Amazing news for the Louvin Brothers! Also great news for Smilin’ Eddie Hill, since he told Acuff-Rose that all the songs were written by Eddie Hill and The Louvin Brothers. Unsure of whether or not they’d be able to keep their radio jobs if they called Eddie out on his bullshit, Charlie and Ira stay quiet about it. Eddie Hill keeps a major piece of the publishing on this first batch of songs, some of which the Louvins would still be recording over 10 years later. The boys take their own songs to Nashville from then on. Neither of them can read or write music, so they have to drive up to Fred Rose’s house and record demos in his home studio anytime they have new stuff.

Fred Rose and Roy Acuff

Fred gets them a record deal with Decca in 1949 – only, The Louvin Brothers don’t have control over what they can record. The songs the label want them to record are never written for a harmony duo. They sit out their Decca contract for a year, rather than release music that doesn’t suit their voices. They move back to Knoxville to play on two live radio shows. The Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round and The Tennessee Barn Dance were seen as sort of minor league versions of the Grand Ole Opry. If you did well there, it usually led to becoming an Opry member and the pay is $200 a week. This is exactly what The Louvin Brothers need, a dream gig.

Ira blows it by getting mad that his mandolin won’t stay tuned and smashing it onstage, right in the middle of a performance. (Acknowledging that some dude in Ancient Greece probably did it, it’s possible Ira Louvin was the first musician to destroy an instrument onstage.) They boys are back to bouncing around between bad jobs. They get another bad record deal with MGM. The Louvin Brothers return to Memphis, both of them working at a post office to make up for how little the radio pay is this time.

They’ve been actively chasing a career in music for over 10 years now with nearly nothing to show for it. Charlie’s twenty-five years old and Ira’s two years from thirty. They’re beginning to seriously consider giving up when they catch a real break in 1952.

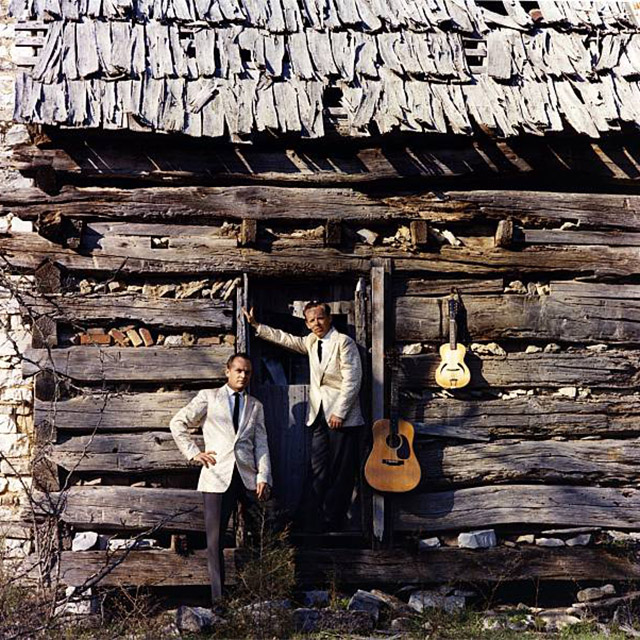

The Louvins with Chet Atkins

Fred Rose is aware The Louvin Brothers are very good and he knows the Decca and MGM deals he got for them were not very good. He keeps trying to make it right and eventually he does. He finds a third record deal for the brothers. This time, with Capitol Records. Fred oversees the recording sessions himself and brings Chet Atkins with him to play guitar. Weeks later, when the first check arrives in the mail, Charlie calls Capitol Records to tell them there’s been some mistake. Someone accidentally sent them a check for $600. He’d never been paid by a record company before.

A Phone Call and a Lie

This all started with a childhood dream of playing on the Grand Ole Opry. The Louvin Brothers decide they’re making money for Capitol Records, so they must be ready for the Opry. They drive to Nashville, to the Ryman Auditorium, ask who’s in charge and play a couple songs for Jim Denny. Denny listens to The Louvin Brothers sing, says “thanks but no thanks” and goes back to whatever he was doing.

This continues to happen over the years. If there’s some Saturday night Charlie and Ira aren’t working, they’ll drive to Nashville and go to The Ryman because they know Jim Denny will be there running the Opry. They get him to duck into a toolshed so they can play him a song or two. Denny rejects them and they drive back home. It becomes sort of a ritual. They know he’ll say “no” again before they even leave home but they still get in the car and go because maybe. Maybe.

Their persistence is rewarded by Charlie being sent into the Korean War. Having served 14 months in the Air Force, he’s still eligible for the draft. Uncle Sam ships him to Korea for another 10 months, yet another aggravating interruption in The Louvin Brothers’ career. Two steps forward, three steps back – every time.

It’s 1953 by the time Charlie gets to come home for good. Their contract with Capitol Records is still in effect and the head of A&R takes on The Louvin Brothers as his own personal project. This is Ken Nelson, producer of Hank Thompson’s “Wild Side of Life” and head of Capitol’s country department. Ken had signed the Louvins on the suggestion of Fred Rose and he now becomes their producer. They get back to making singles and The Jim Denny Rejection Ritual.

It’s fine.

They’re working their way back up to where they were before Korea when Ira talks Charlie into moving to Birmingham for a new radio job there. Then, it’s not fine. After they move to Birmingham, the radio show falls through. It turns out there’s another harmony duo in the area who’ve been adding every new Louvin Brothers song to their own setlist as soon as it comes out. These other guys have been doing this for years and they’ve got a real radio show, so every time the Louvins book a concert somewhere and do their own material, audiences think they’re impersonating this other act.

Charlie can’t take it anymore. They’ve got to get on the Opry. Not only because it’s their childhood dream, either…

America doesn’t have the interstate network for its highways yet. This is decades before cell phones. They were touring off maps, driving on two-lane roads and following scribbled down directions from calls made on payphones. Nashville is already a major travel hub in the South. They have a real highway for anywhere you need to go and, at night, when the airwaves are clear, WSM’s radio signal sends the Grand Ole Opry out to most of the nation. Getting on the Opry will make The Louvin Brothers worth more money on the road, promote their singles to a bigger audience and put them in a location that makes it easier to go play concerts for that audience.

After 15 years of grinding away for scraps, the brothers agree they’re either gonna make it for real or give up for good. Charlie calls Ken Nelson at Capitol Records to let him know The Louvin Brothers are done, unless Ken can get them on the Opry and Jim Denny’s been turning them down for nearly five years. Ken starts laughing.

He tells Charlie that Jim Denny’s just a stage manager at the Opry. All he does is make the schedule for the show and he has no control over who gets on it. This rocks Charlie’s world. He doesn’t know what to say. Ken tells Charlie he’ll call right back because he knows Jack Stapp at WSM.

When Jack Stapp seems wishy-washy, Ken thinks fast. He says let him know soon either way because The Louvin Brothers have an offer from The Ozark Jubilee, in Springfield, Missouri, that the brothers will take if the Opry says no. Now, The Ozark Jubilee was a brand-new show a lot like the Opry, except on television. It was immediately popular on debut, serious competition for Nashville. The Opry had already lost big names to the Jubilee and Jack Stapp didn’t want to see that happen with a new act that could be really good. The Louvin Brothers are on the Friday night Opry that week and the big show Saturday night, if Friday goes well. After all these years, it takes a phone call and a lie to get on the Grand Ole Opry.

The boys head to Nashville.

Revisionist History

New Opry artists go to WSM before the Friday night show and meet all the station executives. According to Charlie, the last office The Louvin Brothers are taken to is that of Jim Denny, the “stage manager” they’d wasted so much time auditioning for over the years. Denny is too busy on the phone to pay them any attention. Apparently, Denny’s just been told that his new publishing company represents a conflict of interest. He must dissolve the publishing company or quit the Opry. Denny’s calling as many artists as he can to try and talk them into leaving the Opry with him. The Louvin Brothers sit there for a while before Ira comes up with a smartass comment to let Denny know they’d got on the Opry without him. The Louvins leave Denny’s office.

Okay.

For everyone who remembers the first episode of Cocaine & Rhinestones, some of this is sounding familiar and some of it isn’t adding up. Right now, you’re probably trying to figure out if Charlie’s full of shit or if I’m full of shit because the story of Ernest Tubb trying to shoot Jim Denny only happens if Jim Denny has control over the Grand Ole Opry. So, why is Charlie Louvin saying that Jim Denny is nothing but a stage manager?

First of all, there are a few verifiably untrue things in Charlie’s book. I’ve found old interviews where he tells stories that later appear in his book with some pretty major details changed.

This kind of thing has a tendency to happen the longer a person lives. We all know the truth of the past can never change but, somehow, the story gets better every time it gets told. One of the things about Charlie’s book is that it was written at the very end of his life. In fact, it wasn’t published until after he died. I’ll talk about this more in the Liner Notes at the end but memory is a funny thing and I don’t believe Charlie is consciously lying. That being said, he is an unreliable narrator. This Jim Denny mixup is one of the smoking guns.

The scene in Denny’s office simply could not have happened like Charlie says it did, certainly not at the time Charlie says it happened.

It’s at least probable that Jim Denny did make those phone calls and it’s a matter of public record that many artists left WSM and the Grand Ole Opry when he did. But what kind of a moron would Jim Denny have to be to make those phone calls with Charlie and Ira Louvin sitting in the room with him?

Next, The Louvin Brothers joined the Opry in February of 1955. Denny was fired from the Opry in September of 1956. In what world does WSM give Denny a year-and-a-half to make up his mind after telling him to fix his conflict of interest or else?

So, okay – it’s possible that Charlie hates Jim Denny for not letting them on the Opry and wants to use his autobiography to make people think that Denny was never very important. A lot of people do hate Jim Denny and Charlie would be just one more on the list. I don’t think that’s what’s going on here. Charlie never seemed that petty, for one thing. But, also, telling the story this way makes The Louvin Brothers look like a couple of dumbasses. Auditioning for the wrong man for five years?! You don’t paint yourself in that kind of light just to kick a little dirt on a relatively unknown guy’s legacy.

Ken Nelson told Charlie that Jim Denny was a stage manager, right before making a phone call that got The Louvin Brothers on the Grand Ole Opry. When someone hands you your life dream gift-wrapped, you aren’t likely to doubt anything else they tell you. The question isn’t, “Why did Charlie believe what Ken said?” The question is, “Why did Ken Nelson say Jim Denny was merely a stage manager in the first place?”

Because Ken Nelson was close with Jack Stapp, Denny’s superior. If you’re friends with the boss, you get to go over everyone else’s heads. It’s possible that Ken had met Denny when he was the stage manager years before this and was unaware that anything had changed since then. Because why would you care if the guy working the front door of a club got a promotion when your name’s on the list at the back door? You wouldn’t. Jim might as well have been a janitor as far as Ken Nelson was concerned.

Now, I can’t give you any answers for why Charlie Louvin would believe the stage manager of the Grand Ole Opry got such a big shot office at WSM’s headquarters or why Charlie would think the owner of a publishing company with Webb Pierce would moonlight as the Opry’s stage manager. What I can tell you is, Jim Denny can’t undercut Jack Stapp’s decision. The Louvin Brothers are on the Grand Ole Opry. Their favorite singer, Roy Acuff, introduces them and the boys are a hit.

The Master Mind

One of the best-selling books of all time is Think & Grow Rich by Napoleon Hill. The front of my copy says “this book could be worth a million dollars to you” and the back says it contains money-making secrets that could change your life, secrets based on Andrew Carnegie’s magic formula for success.

Napoleon Hill

It’s one of those self-help, “be your own boss” things. Although, Carnegie is one the wealthiest self-made men in recorded history and he personally helped Napoleon Hill with this book, so maybe it’s good…

The “Master Mind” may be defined as: Coordination of knowledge and effort, in a spirit of harmony between two or more people, for the attainment of a definite purpose […] No two minds ever come together without, thereby, creating a third, invisible, intangible force which may be likened to a third mind […] When two or more people coordinate in a spirit of harmony, and work toward a definite objective, they place themselves in position, through that alliance, to absorb power directly from the great universal storehouse of Infinite Intelligence. This is the greatest of all sources of power. It is the source to which the genius and every great leader turn (whether they may be conscious of the fact or not) […] It amounts to absolutely nothing until you become active. Every member of the alliance has got to step right in there and start pitching – mentally, spiritually, physically, financially, every way that is necessary. They must engage in pursuit of a definite purpose and they must move with perfect harmony. – Napoleon Hill

I have no idea if either of The Louvin Brothers ever read Think & Grow Rich. It was first published in 1937, which is a few years before Charlie and Ira got serious about pursuing a life in music. So, while it is possible that one or both of them did read the book, I’m not familiar with any evidence that they had.

Still, if you tore out the back pages of their history, it would be the kind of self-made success story we can’t get enough of in America. Two little boys walking down a dirt road, hyping each other up over everything they’re gonna do with their lives when they get bigger. Then they go struggle uphill for 15 years to accomplish all of it. Most people would give up. Most people aren’t The Louvin Brothers.

It’s 1955.

The Louvin Brothers are living in Nashville, official members of the Grand Ole Opry, a goal they’ve had since childhood. They’re playing music and touring with their heroes, recording some of the best vocal performances ever put to tape and trying not to kill each other. They made it to the finish line on a gas tank full of talent and four flat tires worth of bad decisions only to find out that’s where the real trouble begins.

Playing the Opry is everything The Louvin Brothers knew it would be. The Ryman audience loves them. They got signed to a booking agent immediately after their first Saturday night appearance, so, finally, someone who knows what the hell they’re doing is in charge of the Louvins touring. And they’re getting good shows, touring hard – one of the best reasons to be based out of Nashville. But they still have the biggest problem they’ve ever had: God.

God’s music, to be precise.

If We Forget God

Part of their deal with Capitol Records was that The Louvin Brothers would exclusively release gospel records. Capitol already had a brother duo making secular country music and they didn’t feel like they needed two. Gospel music played fine on the Opry. The Ryman used to be a church and that Nashville audience was sitting in pews. Everyone out in America could listen in the comfort of their own home or a friend’s home. The Louvin version of the Lord’s music didn’t play so great out on tour.

Throwing a gospel act on stage in the middle of a bunch of honky tonk acts kills a party full of sinners. You can feel it by the second song, if they’re Ira Louvin originals – full of fundamental certainty and often more than a little judgement: The stories and pictures in most magazines / Now feature new styling unfit to be seen / They’re placed on the newsstand where children can buy / When they go wrong do we wonder why? / If we forget God, His mercy will flee / And sin will cover the land and the sea / If we forget God, Satan will rule / If we forget God, our nation is doomed

On one hand, they could sing so good it was scary. On the other hand, these songs were super Christian. Once the boys got onstage with that routine, some drunks probably thought they’d accidentally wandered into a church service. It made people who wanted to party uncomfortable with how they were living their lives. The show didn’t go over well with church crowds, either. Pianos and organs were godly instruments. Guitar and mandolin, not back then. You’d think this would be something they’d have figured out a long time before this point…

Ken Nelson deserves credit for letting them try some non-gospel originals. The first one The Louvin Brothers come in with is “When I Stop Dreaming,” since recorded by Roy Orbison, Hank Junior, George Jones & Tammy Wynette, Ray Charles and basically anyone else who ever had access to a microphone after hearing The Louvin Brothers version. It’s a hit for the Louvins and all those people who recorded it made the song worth even more money. Our brothers are getting paid. They order two Nudie suits each. Their next single is even bigger. Autry Inman’s “I Don’t Believe You’ve Met My Baby” goes to #1 for The Louvin Brothers.

Louvin Brothers Nudie Suits

Ken Nelson also deserves credit for signing The Louvin Brothers in the first place. Not only did he sign an act that sat out a previous recording contract but he took them on as a personal project, apparently without fully understanding what they can do with their voices. The first recording session with Ken nearly sends him into a fit when he hears the brothers’ singing. He’s blown away.

The song is called “Born Again.” The Louvin Brothers wrote it for themselves and it’s perfectly set up to show off their talent. Charlie’s lead vocals are fantastic but it’s specifically the chorus that’s a revelation to Ken because that’s when Ira comes in. He takes his part way high like he learned from that little girl back at Sacred Harp. Charlie stays lower, matching Ira’s intricate phrasing and pitch control so closely… Well, you can hear it straight away in the intro – the microphone can’t take it. That’s blood harmony. And then you remember Charlie saying he’s never heard a recording of a Sacred Harp singing session that captured what was happening in the room. Maybe it comes through for a second, here and there, and maybe that’s what we’re hearing. I hear it again all over Louvin Brothers recordings… For a second, here and there, it sounds like Arthur Miles’ throat singing.

So Ken Nelson signs these guys without knowing they can do magic tricks with their throats and, then, lets them record secular music against their contract. And they have hit singles with those songs. You’d think everything would be cool. The problem is these are country hits and the first two will be their most lucrative. The closer they get to the 1960s, the less records they sell. Their full-length albums never do really well at the time of release.

This is extremely good country music they’re releasing but Ken Nelson is the head of country at Capitol and this is his pet project. It would be great if they could outsell everyone and nothing he tries can make that happen. This is maybe why Ken Nelson eventually says what has to be one of the Top 5 Stupidest Things Ever Spoken in a Nashville Recording Studio – and that’s saying something…

An Ill-Advised Remark

Now, I’ve already made a point of giving Ken the credit he deserves, here. I’ll also point out that he played a huge role in bringing The Bakersfield Sound to life by working with Buck Owens and many other amazing artists on some of the best material they ever released. You could say he didn’t know what to do with The Louvin Brothers in the studio and you might be right. Still, Ken Nelson was no fool, which makes it difficult to understand or even guess why he would ever tell Ira Louvin that his mandolin was the reason Louvin Brothers records didn’t sell more.

Even if all he meant is the mandolin sound is “old-timey,” there are still so many reason Ken Nelson shouldn’t say this. For one thing, Ira Louvin is a great mandolin player and The Louvin Brothers make old-timey music. Next, The Louvin Brothers are not the only country act with declining sales. Everyone making straight up country music at this time has the same problem: rock and roll. Country sales are down and the country sound is being abandoned, left and right. Many country acts are flirting with rockabilly guitars or embracing that vintage Disney soundtrack vibe of The Nashville Sound, in hopes of crossing over for a piece of the rock or pop audience. Pretty much every episode of this podcast that passes through the mid- to late-50s will at least reference this. There’s no way around it.

with Ken Nelson

It’s not hard to figure out when Ken Nelson put down Ira’s mandolin. The mandolin is all over the 1958 album called Ira and Charlie, recorded in 1957. The year that album comes out, Ken Nelson brings the brothers in for a full week to record enough material for two separate albums – one full of gospel songs that would be called Satan Is Real and the other album ends up being called Country Love Ballads. Guess what was on that one. While you can pick out a mandolin, here and there, buried in the mix as a rhythm instrument, of the twenty-four songs on both albums only four of them feature a mandolin and one of those is just for a couple seconds. Maybe that’s even the song they were getting down when Ken spoke up about it.

Country Love Ballads comes out first. Doesn’t do anything.

Satan Is Real comes out in 1959. A lot of these songs could use mandolin. Instead, we have church organ, which totally makes sense, and a lot of rockabilly electric guitar which totally doesn’t. A single from their 1956 Capitol debut called “Knoxville Girl” goes to #19 on the country charts. This song is not on either of these two new albums. They probably released it as a single because neither album charted and “Knoxville Girl” has been the most requested song at Louvin Brothers shows since 1956. Both of them are sick of playing it.

So Ken Nelson’s big mandolin theory is, obviously, way off. They did things his way and it fixed exactly nothing. One of their older songs becomes a hit, instead. But it’s too late. The damage is already done. Listen to the 1960 album, My Baby’s Gone, and you’ll hear Ken Nelson taking The Louvin Brothers even further away from their sound. You’ll hear a little mandolin because most of the tracks for this album were recorded years earlier, before the shakeup. Now, My Baby’s Gone is really a good album – it’s one of their best – but it features some pretty clumsy attempts at rockabilly production gimmicks. Listen to how goofy Ken gets with the reverb on the vocal track in “Running Wild.” You can find a crappy live recording of the same song from years earlier that makes it clear there are no studio effects necessary for the song.

Anyway, aside from being incorrect, the biggest reason Ken should have known better than to say what he said is because of who he said it to.

One Half That’s True

Ira Louvin is an unpredictably temperamental person. Remember the time he smashed his mandolin onstage? Ruining the best opportunity they had to make it on the Opry at that point in their lives because he couldn’t control his emotions? That wasn’t the only mandolin smashing. It wasn’t only mandolins that got smashed, either. If you believe Charlie Louvin, he and Ira had more fistfights with each other than some amateur boxers have on their entire fighting record.

You can tell Charlie’s spent a lot of time sitting around trying to figure out his brother’s mind. Every so often in his autobiography, Charlie comes up with another guess for why Ira might have been the way he was. If it appears that he’s finding excuses for Ira by bringing up how bad he had it with their father, keep in mind – Charlie isn’t sure if Colonel beat this personality into Ira or wasn’t able to beat it out of him.

As critical as Ira was of any flaw in Charlie’s singing or guitar playing, Ira likely held himself to an even higher standard. He certainly could not handle any criticism from any other people. If Ira played a new song for Fred Rose – one of the greatest songwriters in the world – and Fred suggested a small change of one line, Ira would crumple up the lyric sheet for the entire song and throw it in the trash. Imagine that degree of insecurity. Scrapping an entire work because somebody said it might not be perfect, yet. Starting over from scratch, every time, until your effort receives nothing but 100% praise, as if considering a change to a song would be to admit failure, to accept someone else’s help because you couldn’t do the job yourself. Friends, this is pure Hell in the recording studio. Ira forces take after take after take, often killing the life that was in a song a little more with each repetition.

Charlie guesses a big part of Ira’s problem may have always been God. Ira writes gospel songs more powerful than any sermon you’ll hear, yet his own faith… Well, one night, Charlie walks into the kitchen to find Ira talking to Charlie’s wife. He’s asking if she can prove the existence of God to him…

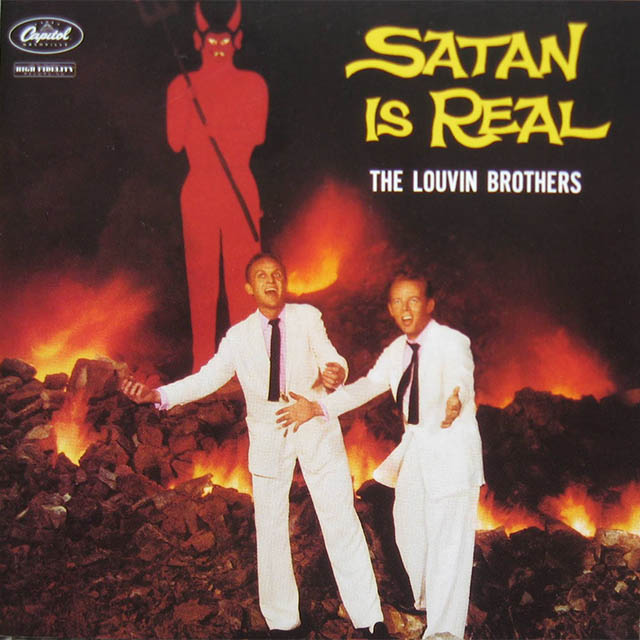

Look at the cover of Satan Is Real. It’s also the cover of Charlie’s book. In a world where Photoshop exists, you’re liable to assume the flames and devil character are edited into the background of a Louvin Brothers promo shot.

Nope.

Ira took control of the art direction for this album cover. They made a 16-foot-tall Satan figure out of plywood, took it down to a rock quarry and set a bunch of kerosene-soaked car tires on fire around it. Then, the guys stood in front of all that, posing, as it began to rain. When drops of water hit the glowing red rocks inside those tires, they’d explode into the air. People usually think the album cover looks ridiculous. You’ll often see it on those Worst Album Covers of All Time lists. But creating this image clearly mattered a lot to Ira Louvin.

The title track of the album is what they call a recitation. There’s a little singing in it but it’s mostly a spoken word number. A tale of what happens in the middle of a service in a little country church. The congregation gets done singing a hymn about the real power of the Lord and, before the preacher can get into his sermon, an old man gets up and warns everyone that Satan is just as real as God: “Preacher, tell them that Satan is real, too! You can hear him in songs that give praise to idols and sinful things of this world! You can see him in the destruction of homes, torn apart! I know that Satan is real…”

It can’t be one half that’s true without the other. This idea means something to Ira. It’s why he gets all hands-on with the album cover. Maybe he thought the presence of evil forces in the world made him less responsible for some of the things he’d done.

The brothers weren’t merely poor while chasing their dream of music. They were poor and dragging families around with them everywhere they moved. Ira’s first marriage was at the age of seventeen and he’d go through two more during the span of The Louvin Brothers’ working relationship, with a fourth at the end. Ira was a womanizer and, when he drank, he became violent. Charlie remembers driving up to a Sunday dinner with his wife, Betty, to discover Ira and his third wife, Faye, fighting in the front yard. Charlie drags his brother away from Faye and he’s holding Ira down when Faye hits Charlie in the head with a cast iron skillet so hard she puts a crack in the skillet.

Charlie waited until he was 22 to marry his wife, Betty, the waitress at a diner across the street from their old Memphis radio job with Smilin’ Eddie Hill. It being right there, they’d all go over to that diner a lot. Charlie started going more often and hanging around longer to spend time with Betty. They married after two years of that and she supported his dreams, sometimes financially, even putting up with Ira. This is impressive when you consider the circumstances. At one point, both Louvin brothers, their wives and their band are all living in the same apartment.

Ira & Charlie with Faye & Betty

That phone call Charlie makes to Ken Nelson to say they’re about to give up for good without the Opry? Charlie had to make that call from a payphone because the phone company had shut off their line at home for not paying the bill.

After the Louvins make it on the Opry, they’re living in Nashville with decent enough money to afford their own houses. Charlie tries to put a little much-needed distance between them. Every time he moves to a house far enough away that Ira can’t drag him in to the drama, Ira buys a house close to Charlie’s new place to keep his lifelong babysitter near.

So that’s the Ira Louvin who Ken Nelson tells his mandolin playing is hurting the sales of Louvin Brothers records. You already know the mandolin went away but how do you think Ira reacted in that moment, in the studio, when Ken Nelson insulted the mandolin to his face with other people standing around and watching? Smash the instrument? Punch Ken? Yell about how it’s all really someone else’s fault?

It’s much worse.

Ira doesn’t say a word. He picks up the mandolin, takes it over to the case, puts it inside and shuts the lid. If featuring the mandolin in Louvin Brothers songs is a problem, then it won’t be a problem anymore. Because, a long time before this, Ken had found a way to show Ira that he knew what he was talking about.

Since Ira was famous for making everyone do take after take, even if Ken told him the first or second take of the song had been perfect, one day, Ken has Charlie and Ira come listen to some old recordings they’d done. He plays them the twenty-sixth take of a song and they all agree that it’s pretty bad. Ira says something like, “Yeah, we just couldn’t get that one right no matter how many times we tried it.” Ken plays him the second take of the song and it’s undeniably much better than the twenty-sixth take. That’s why Ira seems to believe Ken that the mandolin really could be hurting their record sales. Again, it’s not the mandolin. Ken is entirely wrong about it. It’s just that he has one of the few opinions in existence that Ira Louvin respects.

If it feels like I’m making too big a deal out of this, consider that it’s such a serious offense with such grave consequences that Ken Nelson would later deny he ever said such a thing to Ira Louvin at all.

Because Ira putting away the mandolin is the beginning of the end for The Louvin Brothers.

Bottom of the Bottle

Yeah, there was drinking before and it was a problem before. Every story you hear about Ira Louvin acting like an asshole begins with how drunk he was. Those close to him say he was the nicest guy in the world when he was sober. Charlie says Ira’s problem with drinking before the mandolin incident was usually a matter of letting some weekend fun get out of control. Ira’s problem with drinking after the mandolin talk is a matter of beginning and ending a new fifth of whiskey every day, plus beer.

If you thought Ira Louvin was given to smashing a mandolin every now and then before he had a reason to hate them 24/7, go catch a Louvin Brothers show now. While he may not be playing anymore intros or breaks on new songs in the studio, he still has to play the mandolin live to do the old songs right. And he doesn’t seem able to go very long without killing one of them. After a good smashing, Ira sweeps up the pieces into a bag to take it home and glue it back together again. Everybody needs a hobby.

Ira’s graduation to daily drinking isn’t only an issue for his brother and their band out on tour. It takes domestic arguments to a whole new level. If you believe Charlie, there’s never been a fistfight between the two brothers where Ira came out on top. Being taller with a longer reach isn’t always an asset if you aren’t very strong and don’t know how to fight. Even when having a physical fight with his wife, Ira was likely to take a lot of the punches himself. None of his wives ever landed any hits as good as the six bullets Ira’s third wife, Faye, put into him. That story goes like this…

February 1963: it’s a party at Ira and Faye’s place. Shot Jackson, Smiley Wilson and Roy Acuff are all over there. Everyone’s drinking. Faye and Ira begin arguing over whatever excuse they had to fight that night and they take it into the bedroom, so as not to disturb their drinking buddies. In the bedroom, things escalate to the point where Ira has a telephone cord wrapped around Faye’s neck and is choking her. Not how Faye wants to spend her evening. Then, she remembers that Ira keeps a loaded gun under his pillow, so she grabs that gun and starts shooting. Ira takes a bullet in the arm and one in the chest before deciding he should run away, which is when Faye shoots him three times in the back and one more time in the chest after Ira’s on the ground. Lucky for Ira, the gun was a .22 and none of the bullets hit anything important. He survived, though, three of the bullets were close enough to his spine that removing them would risk paralyzing Ira. So those three bullets stayed in his body for the rest of his life. All two years of it.

Ira’s recovery prevents the Louvins from being able to tour for months. Even without the rest period, they’d spent the last few years developing a reputation for concerts that could abruptly end in a temper tantrum at any moment. By the time he can get back on the road, the dates they can book aren’t paying big money. Charlie probably could have lived with that. He made it this far on much less and seems ready to get back out there on the road and show people what The Louvin Brothers can still do. But their days together are numbered.

With everything that’s happened, Ira shows no signs of changing or even wanting to change. The time off at home with his wife and children had surely been an eye-opening contrast for Charlie. Being always away from home and getting cussed out by your drunk big brother is something you can get used to if it’s all you’ve ever done. Then, you spend a few months relaxing at home, realizing all the baby’s first steps and baby’s first words you missed. You learn there’s a different way you could be living your life. That’s a wakeup call.

There’s no big blowup or knock-down, drag-out fight at the end. No fireworks. Quite the opposite. Ira gets pissy first thing in the morning about Charlie setting his mandolin down somewhere Ira thinks it shouldn’t have been set down. That’s it. Such a little thing and Ira doesn’t drop it the entire day. He nags Charlie about the mandolin the whole drive to the show. After the show, Ira tells Charlie he’s breaking up the band and Charlie can go get a job in a gas station somewhere or whatever else he feels qualified to do on his own.

Two to Tango

With the clear good brother/bad brother duality and the gospel connection right there, too many people are quick to call Ira and Charlie a Cain and Abel story. It’s even on the cover of Charlie’s book.

That’s incorrect.

Neither one of them hated the other one. They couldn’t stand each other sometimes and punches were thrown but brothers fight. These two looked out for each other their whole lives.

The first time Charlie was called to sing in front of a crowd, back in the Sacred Harp church, he almost couldn’t make it for stage fright. Ira got him through it. The same thing happened the first time they played the Opry. Charlie’s legs turn to jelly. It’s seeing Ira’s confidence and happiness that keeps him upright.

Ira talked Charlie into doing a lot of stupid things, yeah. Charlie may not have done anything at all without Ira to push him. Ira ruined many opportunities for the brothers, sure. Charlie could have walked away after the ninth or tenth time.

It’s also not fair to say Ira’s voice is what makes The Louvin Brothers’ music remarkable, as many people did at the time and continue to do today. Admitting Ira’s voice is one in a billion, he didn’t craft it as a solo artist. His voice was perfectly molded to fit around the voice of Charlie Louvin and only the voice of Charlie Louvin. Blood harmony. To dismantle The Louvin Brothers’ sound and critique it as anything other than a single, cohesive unit is to miss the whole point.

You can not lay all the credit for their success or all the blame for their failure at the feet of either Louvin brother. Through good and evil, it takes two to tango. Twenty years in and Charlie finally realizes that, by not walking away from Ira, he’s passively endorsed everything Ira’s done. Ira hasn’t ruined Ira’s reputation. Ira’s ruined the reputation of The Louvin Brothers. Charlie’s a Louvin Brother.

Fans don’t walk away from one of the mandolin meltdown shows talking about how nice everyone else on the stage seemed except for the one who threw a fit. They tell their friends buying a ticket to a Louvin Brothers concert, that’s a gamble with their money. The promoter tells other promoters not to book The Louvin Brothers unless they like angry audience members demanding refunds. Charlie’s name gets lumped in with all this, just as much as if he’d been the one throwing a tantrum onstage.

When Ira tells Charlie to start looking for a job at a gas station because the act is over, it’s not the first time Ira’s said something like this. When Charlie tells Ira that he’s right, they had just played the last Louvin Brothers concert, it is the first time Charlie’s ever said anything like that. He means it.

The Louvin Brothers break up in August of 1963.

Born Again

When Charlie gets home he straight away takes his family on a summer vacation to Florida, even going through Sand Mountain to pick up his parents. After a few days in nice weather, surrounded by people who love him and act like it, Charlie’s back in Nashville and starting to get used to the idea of moving forward on his own with music. He calls the Opry and asks if they’ll have him as a solo act. They book him on the next show.

I don’t think anyone can imagine what it’s like to be Charlie Louvin getting ready to perform that night. He’s aware of how many people think Ira’s the one with the talent. For all Charlie knows, he’ll go out there to sing and some smartass will yell “where’s your brother?!” to set off the whole crowd throwing things at him. I’m sure that and a hundred other scenarios ran through his mind before he went onstage.

Of course, it went fine. The audience applauded when he came out and applauded when he was done. Like the first time, he performed on the Friday night show, again on the Saturday night show and, then, got a booking agent to start getting him some dates. This time as a solo act.

If Charlie was still nervous about breaking out on his own after his solo performances at The Ryman, he shouldn’t have been. His first solo album in 1964 put four singles in the country Top Ten. The Louvin Brothers never had an album like that. Charlie’s first big hit is a cover of Bill Anderson’s “I Don’t Love You Anymore” that goes to #4 but my little sister likes “See the Big Man Cry” a lot more. That one went to #7.

When Charlie’s album comes out, Ira’s living back on Sand Mountain. He’d sworn he was done with the music business when Charlie split with him. Colonel gave him a couple acres and Ira had a house built on it for himself and his fourth wife, Anne. We don’t really know what he’s doing for money while he’s out there. It’s likely the low cost of living on Sand Mountain could have been covered by Ira’s share of the Louvin royalties. Despite all that, it isn’t long before Ira starts making moves towards his own solo work.

If he really believed that Charlie was less than half the draw for The Louvin Brothers, Ira could have been inspired by how easy it was for Charlie to go solo. Ira’s first single is a silly song called “Who Throwed That Rock.” I find the b-side a lot more interesting for this story. It seems Ira wasn’t fully ready to step out on his own or he wanted to see if Charlie really was replaceable. Because, if anyone could do Charlie’s parts, then Ira could keep using all his best magic tricks from the duet act. Listen to “Make Believe It’s Me” to hear a duet between Ira Louvin and his wife, Anne.

Needless to say, Charlie Louvin was not so easily replaced. The single didn’t do anything and neither did the one he put out after that. Still, Ira got some tour dates together and he hit the road with Anne.

Are You Afraid to Die?

In June of 1965, Anne and Ira are riding through the night from Kansas City to St. Louis, Missouri, when the car they’re in is struck head-on by a drunk driver veering into their lane. Everyone in both vehicles is killed. The driver and front seat passenger in both cars die on impact. Anne and Ira are in the back seat of the car they were in. Ira bleeds to death before any help arrives. Anne may have survived except the first hospital where she’s taken is too busy or unequipped to treat her and she dies before reaching the second hospital.

This is all tragic for many reasons.

It would later come out that Ira had telephoned his mother in the days before the wreck to say he realized that touring to play music was the major cause of all his drinking problems. He told Georgie that he was going to do these dates to fulfill these contracts and then quit music to begin life as a preacher, his true calling. It’s sad that we’ll never know if Ira really could have changed his life for the better.

It’s also sad because Ira’s death is the true end of The Louvin Brothers. They’d broken up two years earlier and performed together again twice before Ira died. Once, when Charlie arranged a reunion show to help Ira out with some money problems and, another time, when Ernest Tubb got them to sing together on the Midnite Jamboree. One performance together per year they were broken up. Especially if Ira had been able to clean up his act, I’d say the odds of The Louvin Brothers working together again were pretty high until Ira was killed.

Charlie continued on with his own work for the rest of his life, maintaining a steady output and a decent showing on the charts almost into the ’90s. His final album came out in 2010, making his solo career last about 3x longer than that of The Louvin Brothers. Charlie died of cancer in 2011. He and Ira are buried next to each other in a cemetery near Nashville.

There are things we hear in music today that we never would have heard if not for The Louvin Brothers.

Thank you for listening to (and reading) Cocaine & Rhinestones. Every episode is written and produced by me, Tyler Mahan Coe. You can find me on Twitter and Facebook at that name, if you’d like.

I want to mention that I’m running a giveaway for listeners to enter for a chance to win my copy of one of the many books I had to read while making this first season. I also want to mention the Facebook group that I started. It’s not a group for this podcast but if you like this podcast then you’ll like this Facebook group. When I’m working on an episode and can’t find the answer to a question, I’ll post about it in there and usually get some pretty good answers. There’s a lot of first-hand knowledge in that group, if you know what I’m saying.

Please recommend this episode to one person in your life. If anything I talked about reminded you of a conversation you had with someone, tell them this episode reminded you of that conversation. By now, I’ve received enough feedback from people who never cared about country music before to know that you don’t have to be a fan of country music to enjoy this. I see a lot of people sharing it and saying things like “if you like country music…” or “if you’re interested in country music, you should check this out.” I mean, you should definitely check this out if you like country music but even if you don’t, people seem to like it. But, check it out: you and I both know if they keep coming here for these great stories then they’re going to start liking this great music. It’s only a matter of time and then you’ll have one more person to listen to good country music with! This is a win/win situation for everyone.

Oh, and if you’re a music writer reading this or an editor of a magazine or something, there has been exactly zero coverage of this podcast by mainstream music media and Cocaine & Rhinestones still hit the #9 position of all music podcasts in iTunes the first weekend it was added to their directory. It ranked higher than all but one of NPR’s multiple music podcasts. That means, it ranked higher than every other music podcast in the world except for eight of them. I’m not affiliated with any sort of podcast network that helped me with a push on the launch date. Nothing special happened, promotion wise. All I did was put it online and that’s what happened. There have been a few blog posts – shoutout to Saving Country Music, Belles & Gals and Country Music News Blog – but that’s it. Zero presence in the mainstream media. So I think you’ll be surprised at the response a feature on this podcast gets from your readers. Send me an email and let’s find out.

This episode is brought to you by drunkMall.com. You don’t have to go to the mall to do your Christmas shopping this year. You can stay home and go to drunkMall.com instead. The website is slightly Not Safe for Work but you should be using it while you’re at home anyway because that way you don’t have to wear pants. drunkMall.com has gift guides to help you find exactly what you need for your husband or wife or boyfriend or girlfriend, moms, dads, coworkers, best friends. There are even things that would be perfectly acceptable to give to children, if you have to buy something for a kid. (But do not show this website to that kid.) So go hit up drunkMall.com whenever you want. It’s always there and it’s always open.

Next week on Cocaine & Rhinestones, I’m talking about Shelby Singleton. That’s not a name many of you will know. He was a behind the scenes player and the scenes he was behind were major scenes. I don’t want to give too much away but I can tell you that next week’s episode is the first in a three-part series on the song “Harper Valley PTA.” Can you believe that? Three episodes of a podcast about one song? Well, maybe I’ll talk about some more stuff than that but I don’t believe that song would have been what it was without Shelby Singleton, which is why my “Harper Valley PTA” series starts off with him. Come back next week.

-TMC

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [linked, if available]:

- Arthur Miles – “Lonely Cowboy, Part 1” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “I Wish You Knew” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “Mary of the Moor” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “When I Stop Dreaming” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Cork Sacred Harp – “183 Greenwich” [Soundcloud]

- The Louvin Brothers – “Low and Lonely” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Roy Acuff – “Low and Lonely” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “Knoxville Girl” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “Kneel at the Cross” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “The Family Who Prays” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “Love Thy Neighbor as Thyself” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “If We Forget God” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “I Don’t Believe You’ve Met My Baby” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “Born Again” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “Tennessee Waltz” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “The Drunkard’s Doom” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “Running Wild” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “Satan Is Real” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “The Great Atomic Power” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Charlie Louvin – “See the Big Man Cry” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ira & Ann Louvin – “Make Believe It’s Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ira Louvin – “Something Has Just Got to Give” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Louvin Brothers – “I Can’t Keep You in Love with Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Excerpted Video

These video clips were either excerpted or referenced in this episode of Cocaine & Rhinestones. They may be removed from YouTube in the future (for any of a number of reasons) but, for now, here they are:

Commentary and Remaining Sources

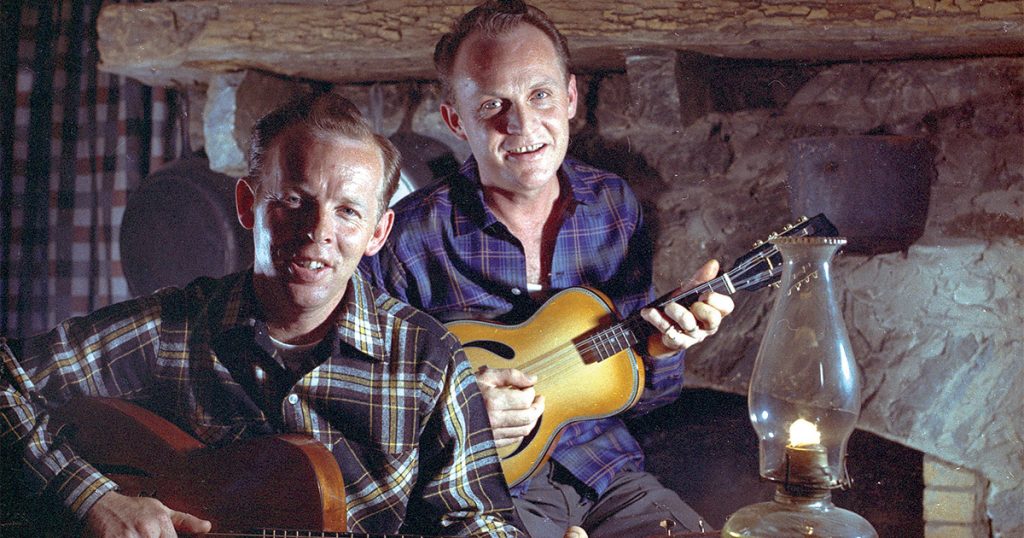

This episode mattered so much to me. You can tell The Louvin Brothers’ music is nothing less than an obsession for me and I think their personal lives are just as gigantic. It’s as if you’ve got the two roads a musician can travel through country music and these brothers are walking, hand-in-hand, each of them on the separate road, from beginning to end. It really reminds me of something you would read in Greek mythology and they even seem to embody these notions, physically. If you look at pictures, Ira is tall and lanky, his face is sharp and angular, he’s got these arched eyebrows – all he’s missing is the devil horns. Then Charlie is smaller with a rounder face like a cherub, you know, like a painting of a little angel guy. You could cast them as those little angel and devil cartoon characters that pop up on the main character’s shoulders when he has a hard decision to make. I can not believe there hasn’t been a movie made about The Louvin Brothers by now. I mean, fuck Walk the Line, let’s make Satan Is Real. Hollywood, let’s do it.

I’ll never forget the first time I read Charlie Louvin’s book. It was definitely in one sitting. There’s no taking a break when you’re in that. It’s short chapters – boom, boom, boom – and it transports you straight back to that time and place. Knowing that not everything in the book is true changes nothing for me. It doesn’t take any of that power away, not for me. People like me, who need to find out what really happened, we should never be solely relying on artist autobiographies for that anyway. They’re notoriously full of shit. I can’t imagine anyone ever treating an artist autobiography as the definitive source for something. This is why I spent some time in the middle of the episode on the Jim Denny thing, instead of saving that for the Liner Notes, like I usually do. It’s really important for us to recognize that even though we love the music made by these people and we respect them and we love the stories that they tell us, that does not mean their own word is the ultimate authority on their own lives or careers. A lot of the time, they have no idea what they’re talking about and, the more famous a person is, the less likely it is someone’s going to tell them that. Satan Is Real captures one man’s experience in life and in country music. It is entirely subjective. While I do believe Charlie Louvin held every word in his book to be true, that is, quite definitively, not the case.

In a book called In the Country of Country, Charlie tells the writer Nicholas Dawidoff that Ira couldn’t be admitted to the hospital when he was shot until Charlie got there to sign some papers. In Satan Is Real, Smiley Wilson has already signed the papers to get Ira admitted before Charlie arrives.

In the same book, Charlie says that Faye cracked a cast iron skillet on Ira’s head. So, either this woman had a real talent for putting cracks in cast iron skillets by cracking people in the head without killing them, or maybe the version where Charlie takes the skillet in the head is the true version and that’s why he gets these stories mixed up sometimes. I don’t know.

There’s some stuff I couldn’t find a way to get into the episode about Charlie and Ira having Faye committed to an insane asylum after she shot Ira. I guess there was some way that Charlie was legally able to get her committed? So, rather than just getting a divorce, Ira talks Charlie into having Faye thrown in the cuckoo’s nest then acts like it was all Charlie’s doing. Roy Acuff and a bunch of Opry people get involved. I think they eventually have to get the governor of Tennessee involved because Charlie can’t just sign her back out. I don’t know, though. It would have taken me a long time to research what really happened and a lot of time in the episode to get into it. Ultimately, I felt like it was a tangent, so read Charlie’s book if you want more of that.

If you listened to the Liner Notes of the first episode of Cocaine & Rhinestones, you heard me talk about a rumor that Clyde Moody helped start regarding Ernest Tubb dying broke and alone in a hotel room. I do not believe that rumor could possibly be true and I stated my reasons in those Liner Notes. Charlie prints the rumor in his book as if it were fact. Again, I believe this is a case of Charlie Louvin being too trusting of the things people say to him.

Also probably the case with Charlie talking about Ira recording a jinxed song before he died, which would be Tommy Hill’s song “I Can’t Fly,” also known as “You’re Looking for an Angel.” Charlie writes that Jim Reeves recorded the song two months before his plane crash and there were maybe ten other artists who all recorded the song and all died prematurely. In reality, Jim recorded the song years before his plane crash. Tommy Hill’s sister, Goldie, recorded the song in 1960 and lived until the year 2005. I couldn’t find anyone else who’s even recorded the song but, seriously, if anyone has proof that this song might be cursed then, right now, I’m begging you to email that shit to me. Let me know. I would love to do an episode on a song that killed 11 people. Send me that.

I truly do not know if Ira Louvin meant what he said in his phone call to Georgie, preceding the car accident. We do know there was a warrant out for Ira’s arrest at the time of his death, related to a DUI. That doesn’t really mean anything either way, though. The DUI could have been the wake-up call he needed to make a change in his life or it could have been an indicator of business as usual. We will never know.

I forgot to say in the episode that there was some family resentment about the boys changing their last name. Incidentally, the Louvins are cousins with JD Loudermilk, the songwriter of “Ebony Eyes,” “Tobacco Road” and “Then You Can Tell Me Goodbye.” His last name did not seem to be a problem.

One person I do want to make sure to mention is Paul Yandell, the Louvin Brothers’ guitar player in the second half of the 1950s. Paul was a brilliant fingerstyle guitarist and he put up with a lot of Ira Louvin’s bullshit on tour. You can see Paul at work in at least one of the video clips in this post.

Something I haven’t talked about but I should is, every single episode of this show, I cut out one of my favorite songs or I cut out a good little story from the episode. The reason I do that is because I know some of you are finding out about these artists for the very first time and I want to leave something out there for you to find on your own. That’s one reason I keep telling you to read Charlie’s book if you want more – there’s plenty more there because I left a lot of it alone. I can also tell you, for this episode, I cut a song from Ira Louvin’s solo album. It’s called “Bottom of the Bottle.” If you haven’t heard that, you really should hear that.

I misspoke in the sympathetic resonance segment when I said the other strings will begin ringing without anyone or anything touching them. Sound waves are things. We can’t see them but they are physical things and they do touch the other strings and that is what causes them to resonate – with sympathy.

In addition to the books I’ve already mentioned, Colin Escott, one of the best music writers that I know of, wrote a book on the Grand Ole Opry, called The Grand Ole Opry: The Making of an American Icon. Charlie Louvin talks more about his early listening to the program and a few more details that I left out regarding Roy Acuff’s status as a legend in the minds of the young Louvin Brothers. The entire book is worth your time.

One more thing: I am not in any way endorsing Think & Grow Rich by Napoleon Hill. If that type of book works for you, that’s great – whatever gets you through to the other side of your goals – but I want to be absolutely clear that I am not saying that book or any other book holds the secret to success. I’m not a rich person. You shouldn’t be taking my advice anyways. Type “Napoleon Hill scam” into Google and just spend 5 minutes reading what comes up. Here’s a very long blog post that claims to reveal how Napoleon Hill’s “business practices” found him on the wrong side of the law. According to this blog post there seems to exist only one photograph of Napoleon Hill with any of the powerful and genius men he claims to have interviewed. That is a photograph with Thomas Edison, which, according to an article written in 1923 was simply a matter of Napoleon going to a convention where he knew Thomas Edison would be and asking to have a photograph made with him. At least one of Carnegie’s biographers failed to find any evidence that Napoleon Hill and Carnegie had ever even met.

Okay, that’s it.

-TMC

Come back next week to have your mind blown by stories of a guy most of you have never heard of, Shelby Singleton.

Musical Overtones and the Harmonic Series