Everyone loves Ernest Tubb.

So when he straps on a gun belt one night to head across town and snuff out a character named Jim Denny, well, you might guess that ol’ Jim had it coming. Maybe he didn’t, maybe he did…

For you to make up your own mind, we’ll need to go behind-the-scenes of 650 AM WSM in Nashville, The Grand Ole Opry and the world of country music publishing companies.

This episode is highly recommended for fans of Jimmie Rodgers, Johnny Paycheck, Justin Tubb, George Jones, Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley, Hank Williams, Roy Acuff and Matlock. Yes, Matlock.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

In addition to The Library, these books (and DVDs) were used for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

The Texas Defense

When Andy Griffith passed away in 2012, CNN covered his death off-and-on the entire day.

You’ve all seen this type of news coverage before – an overview of the career, images of the star in their prime, phone-in conversations with other celebrities who were close with the departed. Larry King is one of the people who called in to talk that day. He’d had Andy on his various shows numerous times – and he mentioned something in passing that’s really interesting…

What Larry said, is that a lawyer named Percy Foreman was the man who inspired the character Matlock. This was a weird thing for anyone to say because most people, even today, believe that character to be based on a different lawyer named Bobby Lee Cook. However, in 2015, three years after Larry King said something that most people would assume was incorrect, the creator of Matlock did confirm that the character was based on Percy Foreman.

A criminal defense attorney from Houston, Texas, Percy lost only 53 of the 1500 cases where clients of his faced the death penalty, with only 1 of those losses resulting in an actual execution. Percy was able to achieve this record by being an incredible lawyer, no denying it. But also due to the Texas court system’s practice of using juries to determine guilt as well as sentencing in the case of a guilty verdict.

So, instead of one judge – who’s heard it all before – determining his client’s fate, Percy had 12 average citizens from the local community sitting right there, waiting to be convinced that the victim in this situation wasn’t a victim at all.

They were up to no good!

The community was far better off without that element in it!

Even if his client had killed ‘em, well, Hell… They needed killing!

Foreman called it Misdemeanor Murder. That’s where a jury might convict you of ending another person’s life and send you on your way with the type of punishment you’d receive for a misdemeanor crime, often nothing more than probation. No time, at all. It’s essentially a sanctioned form of vigilante justice.

Percy Foreman had such a long run of wins with this strategy that it’s still being used in Texas today. People who have conversations about this sort of thing will sometimes refer to it as The Texas Defense…

Jim Denny

Now, Jim Denny… wasn’t from Texas.

He was from Tennessee.

The Buffalo Valley area, about 60 miles east of Nashville, was a real poor area in which to be born in 1911. When a 16 year old Jim Denny got hired to work the mailroom of WSM Radio’s parent company, he must have seen it as an opportunity to make something out of himself.

Denny got this job in 1927. That year, the young radio program WSM Barn Dance was referred to as the Grand Ole Opry for the first time, on-air. Every time an odd job came up at the Opry, Jim would take it, so he could hang out backstage, see the artists, and see how the show was made. Within 20 years, Denny had worked his way up to director of the Artists Service Bureau at WSM, which meant he was in charge of booking the acts on the Opry.

Jim Denny & Jim Reeves

There are a few funny things from Jim Denny’s time at the Grand Ole Opry…

Like, the one about Elvis Presley’s big debut…

Elvis was still a teenager when Denny did Sam Phillips the favor of letting Elvis come on the show to play his not-country arrangement of Blue Moon of Kentucky. It didn’t go well. Denny supposedly told Elvis backstage, “You ain’t goin’ nowhere, son. You ought to go back to drivin’ a truck.”

Denny’s also the guy who fired Hank Williams – over the telephone.

And there’s the time when Jim made Johnny Cash wait outside his office for 2 hours before letting him in to ask why Cash should be allowed to play on the Opry. Cash mentioned that he presently had a song called “I Walk the Line” in the top ten…

Jim Denny was what many people referred to in those times as a “hard man.”

Today, I think they’d have some different words for him.

And that’s why Ernest Tubb tried to shoot him in 1957.

Young Ernest

It’s shocking to hear Ernest Tubb’s name associated with any kind of violence, whatsoever. There are plenty of stories about him and most of them are about how great a guy he was. He had an adorable nickname – “E.T.” – you can hear admiration in the voice of everyone who calls him that…

Crisp, TX is a ghost town now. Ernest Tubb was born there in 1914 – into a family of sharecroppers. Like most sharecroppers’ children, Ernest grew up working on farms all over the area. Long days in the field, entertainment from a stereo in the evenings, an early bedtime and you get back up the next day to do it all over again. Typical day for a sharecropper.

Like a great number of artists we’ll learn about in future episodes, it was all over for a 14-year-old Ernest Tubb the first time he heard Jimmie Rodgers sing. The obsession was instant and it would steer the course of the rest of his life. Hearing Jimmie Rodgers is what led Ernest Tubb to decide he simply had to become a country singer. It’s also – very specifically – what caused him, three decades later, to want to shoot a .357 magnum at Jim Denny.

In 1933, Jimmie Rodgers died young of tuberculosis symptoms. He was 35.

The death of his idol was extremely upsetting for Ernest. However, it also made him realize that he was going to have to get serious about chasing his dreams. He moved to San Antonio, made a few guest appearances on a friend’s radio show and managed to secure his own early morning show, which aired twice a week. Not bad for a 19 year old kid.

But don’t get the wrong idea.

He was nowhere near the big time. And the pay was quite slim. E.T. had to keep two other jobs besides the radio gig. Some days, he was a ditch digger. Other days, a drug store clerk. Holding down three jobs at once was necessary to support himself and his young wife, Elaine. They didn’t waste any time before starting to have kids, either.

Young Ernest Tubb

Ernest was more than happy to work hard if it kept him moving toward the life of his hero, Jimmie Rodgers.

He’d had this small picture of Jimmie for years now and it was in pretty bad shape. So he got a phone book and looked up the number for Jimmie Rodger’s widow, Carrie. He called her on the phone to explain that he was such a big fan and to see if she happened to have a bigger, better photo of Jimmie that Ernest could have.

Maybe even one that was autographed…

Carrie was super nice and said she did have such a photo that Ernest could have. She went so far as to invite him out to her house in Kerrville, TX, to get the picture. Ernest drove out there the next Sunday he wasn’t working, taking Elaine and baby Justin on the trip. They’d planned to stay for maybe ten minutes and ended up hanging out for over two hours – looking at costumes, guitars and pictures brought out by Mrs. Rodgers; hearing her stories about how high on the hog they’d lived merely a few years earlier. E.T could never have guessed when he woke up that morning that he’d be laying down to sleep that night having held Jimmie Rodgers’ signature Martin acoustic guitar with Jimmie’s name inlaid in pearl across the fretboard and the word “THANKS” written on the back – upside down – so Jimmie could flip it over to show audiences.

Choose your biggest dead hero and try to think of how you’d feel if a similar experience happened to you – it’s mind-blowing!

Okay, now add this on top of that…

A few months later, Carrie Rodgers called Ernest to say she’d listened for his radio show as he’d asked for her to do. On one hand, she offered to help E.T. out with the access she still had to music business big shots. On the other hand, she didn’t think he sounded like Jimmie Rodgers when he sang, which is basically the only thing in the world Ernest Tubb wanted to do in this phase of his life. And everyone around him had told him that’s exactly what he’d been doing this whole time…

Anyway, she still hooked E.T. up with Elsie McWilliams, the writer of a few great Jimmie Rodgers songs. Ernest Tubb made a couple of records that didn’t sell very well, did some touring and ended up back home – doing low paying radio again and working 2 or 3 side jobs like before. Driving around a beer truck was one of them, this time.

After a while back at home, Ernest had to have his tonsils taken out. He’d later say the doctors told him not to sing (or yodel) for a while after the surgery but he didn’t listen. Jumping right back into his normal routine re-injured his throat.

It changed his voice forever.

No more yodeling.

A New Voice

Ernest held a self-deprecating sense of humor about his new voice for the rest of his life. He loved to say that “9 out of 10 guys sitting in bars around the country could sing better” than he could.

I don’t know if he really believed that. It’s always been strange to me.

I think George Jones – indisputably, the greatest country singer in history – is exactly what happens when you add Ernest Tubb’s new singing style and Roy Acuff’s voice together. Now, George would have told you Hank Williams was his favorite singer but you don’t get Hank without Ernest and Roy. I’ve seen Lefty Frizzell named as an influence on George. Lefty borrowed from Ernest as well. However you want to say we got to George Jones, it always comes back to Roy Acuff and Ernest Tubb, two singers George did grow up listening to on the Grand Ole Opry.

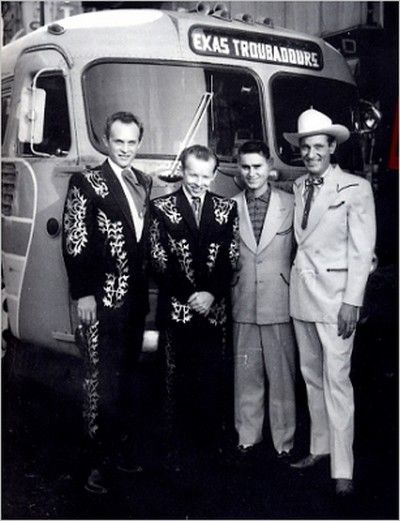

The Louvin Brothers with George Jones and Ernest Tubb

Now, the part of Ernest you can hear in George is the tendency to hold on to a note for longer than you’d expect,

picking the melody up and putting it back down in ways that are impossible to predict when hearing them sing a song for the first time – no matter if it’s a song you’ve heard performed by other people.

It’s possible Ernest really didn’t like his new voice…

About a million people disagree with his opinion.

He had that tonsillectomy in 1939. In 1940, he had his biggest hit, “Walking the Floor Over You.” The song is still synonymous with the name Ernest Tubb. If someone only knows one Ernest Tubb song, it’s usually this song.

E.T. was finally big time.

A Helping Hand

He joined the Grand Ole Opry in 1943 and formed the first incarnation of The Texas Troubadours. Tubb would stay working for the rest of his life, so members of the Texas Troubadours would be replaced every now and then. Buddy Emmons, Jack Greene, Billy Byrd, Leon Rhodes and Cal Smith were only some of the notable players who joined the band on their way up the ladder. This was the first way Ernest found to extend a helping hand to younger musicians like the hand Carrie Rodgers had held out to him…

He was the first one to call names out on records and he loved doing that. He loved the guys. They were a big part of his show and he wanted to make sure they got the credit for it. So he started calling their names out when they took a course. He was never jealous of anybody in his band outshining him. You know, he didn’t mind that at all – as he proved with Jack Greene, Cal Smith, of course he had The Wilburns with him for a while, Skeeter worked some dates with him, George Jones, Stonewall Jackson… and he was always pushing them. And he, like Roy [Acuff], I think, understood that the bigger they became the bigger he became. – Justin Tubb

Now, George Jones and Stonewall Jackson were never Texas Troubadours. Justin meant E.T. took those guys out on tour with him as opening acts to help them build their own following. And, often, he did a lot more than that…

Ernest… One time, I was hangin’ around the streets and it was snowin’. Buddy Emmons took me on [the bus] to meet him […] I had met him but, I mean, I wanted to sit and talk with him. They was gettin’ ready to go on tour and I didn’t have anywhere to stay, you know. I was at that stage in my life. And, evidently, Buddy had told him that because we got on [the bus] and […] I talked to [Ernest] a while and he said, “Well, it’s about time to leave.” […] He asked me if I was workin’ and I said, “No.” He said, “You are now.” He was going on, like, ten days out in Texas and it was snowin’ here in Nashville and I had nowhere to… You know, I was in that place… He took me on the road. Wound up giving me a suit! I didn’t have nothin’ to wear so he gave me one of his old suits and took it to the cleaners and I had it cut down the first date we got in Texas. And it was so – there was two pockets in the back! That’s how much they had to take [it] up! And I still got a picture of me in that suit. He let me go out and I opened his show for him for ten days and he fed me and at the end of the tour gave me some money. So that’s the kinda guy he was. – Johnny Paycheck

You can’t tell the Hank Snow story without talking about Ernest Tubb.

E.T. told Johnny Cash not to smile when he performed “Folsom Prison Blues,” so people in the audience could really feel the song.

Cash never forgot the advice.

Hank Williams Sr. was heavily influenced by Ernest’s music and Ernest is the one who convinced the Grand Ole Opry to bring Hank back after his initial failed audition. E.T. got Hank to promise he wouldn’t touch any booze for three months to swing that one…

In 1947, enough radio listeners wrote letters complaining of not being able to find his music so that he launched the Ernest Tubb Record Shop in Nashville. If you couldn’t make it there in person, they’d ship records directly to you. It was a game-changer for country music fans and would help keep the music alive when rock and roll steamrolled America in the fifties.

The record shop operated at a loss of $10,000 a year for the first two years it was open but Ernest knew how important it was and he kept it alive. The Opry was a great promotional tool for him and he’d started his own show on WSM in the following time slot. When the Opry was over, fans could stay tuned in for the Midnite Jamboree. Ernest played host to Opry stars and newcomers alike – making sure to remind you this music was available for mail order from Ernest Tubb’s Record Shop. He took the chance to keep Jimmie Rodgers memory alive, pitching his records as well.

Ernest Plays on Midnite Jamboree

Ernest never grew out of his fascination with Jimmie Rodgers and he never stopped repaying his debt to Jimmie’s widow, Carrie. Jimmie’s death had left Carrie in a pretty bad financial situation but she still got money from the sales of his records, which were declining. Ernest realized the more Jimmie Rodgers records sold, the better off Carrie would be. So E.T. pushed those records as hard as he could. Carrie loaned and eventually flat-out gave him that guitar of Jimmie’s, which is why you’ll frequently see pictures or videos of Ernest Tubb playing a guitar that says JIMMIE RODGERS on it.

In 1953, Ernest helped found the Jimmie Rodgers Memorial Festival in Rodgers’ hometown of Meridian, MS.

That’s a standup guy.

You can find plenty of people who’ll say the same thing about Jim Denny.

Remember Jim?

Poor kid from TN? Worked his way up from the mailroom to become director of Artists Services at WSM and manager of the Grand Ole Opry?

Opry Monopoly

Director of Artists Services was a fancy way of saying Denny booked the musical acts that played on the radio station as well as the Opry. Denny was a powerful man in Nashville and he acted like he knew it.

Where Ernest Tubb built a reputation for helping young musicians, Jim Denny had a reputation for acting like a dick. The Johnny Cash who E.T. gave advice to is the same Johnny Cash who had to wait two hours outside Denny’s office.

Jim Denny might not have been a dick. He could have simply been a businessman who paid more attention to the bottom line than how many friends he had.

Denny’s the guy who had to be convinced to let Hank Sr. onto the Opry and he’s the guy who called Hank to fire him over the telephone. But Ernest Tubb was standing in Denny’s office when that phone call was made. He said he saw tears in Jim’s eyes.

Hank had missed a scheduled Opry appearance, most likely for no good reason other than that he was drunk. Denny said he thought firing Hank would make him realize he needed to get his act together.

That’s not what happened.

Hank Williams died 4 months after being dismissed from the Opry.

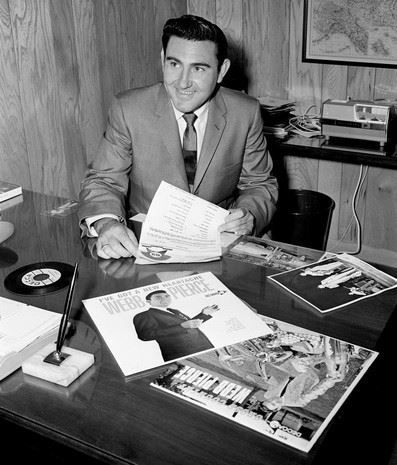

It’s tragic but you can see how Jim Denny thought he was doing the right thing in that situation. This is important to recognize because the year Hank Williams died is the same year that Jim Denny formed Cedarwood Publishing with Webb Pierce.

Webb Pierce at Cedarwood

If you don’t know what a publishing company is, it used to be the heart of the record industry. On the surface, a publishing company’s purpose was to make sure sales royalties were going to the right place. They took a big percentage to do this so anything that could be done to make a hit out of one of their writer’s songs they’d do it. And if they forgot to send you your whole royalty check sometimes, well, shit happens…

Roy Acuff and Fred Rose had started Acuff-Rose Music back in 1942. So many country writers were being screwed over by publishing companies based out of other cities that there needed to be one in Nashville – an honest publishing company, run by country artists, for country artists. They were the best game in town until Jim Denny formed Cedarwood in ’53.

As head of Artists Services at WSM and manager of the Grand Ole Opry, Jim Denny controlled who got to play on the Opry, their place in the lineup and how long they got to play.

Can you see where this is headed?

If Jim Denny owns a country music publishing firm while retaining singular control of the most popular country music radio program in America, then he’s essentially printing his own money.

Once he’s got a writer signed to Cedarwood, then he’s getting a huge piece of any money their songs make. If that writer also wants to be a performer, “Congratulations, you’re on the Opry tonight!” If the writer doesn’t want to be a performer, “Congratulations, Webb Pierce is the biggest star on the Opry and he’s playing your song on The Grand Ole Opry tonight!”

Roy Acuff was pissed off and he didn’t stay quiet about it. Artists signed to Acuff-Rose had a tendency to see Roy’s point. Artists signed to Cedarwood had a tendency to think Jim Denny wasn’t doing anything wrong.

Weird, huh?

Long story short, in 1956, WSM fired Jim Denny over his conflicts of interest.

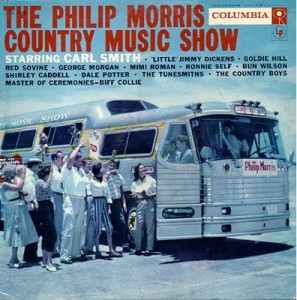

Jim started a booking agency and signed most of the Opry artists, some of whom had resigned when Denny was fired. Then Denny contacted the Philip Morris Tobacco Company. Their competition in the cigarette business, RJ Reynolds, was a sponsor of the Grand Ole Opry. So, when Jim Denny called with a chance for them to get their product associated with all those acts, Philip Morris wrote a check big enough to fund the biggest country music package tour anyone had ever seen.

Half the Opry lineup these fans listened to every Saturday night was coming to stages across America for live appearances. With Philip Morris paying for everything, the admission was even free!

It looked as though everyone was getting what they wanted – until the Philip Morris Country Music Show booked a stop in Meridian Mississippi on the same week as the Fifth Annual Jimmie Rodgers Memorial Festival.

But it was worse. The Philip Morris show would take place on the second night of the two-day Jimmie Rodgers festival.

Philip Morris Country Music Show Compilation from 1957

For 5 years, Ernest Tubb had worked to grow the Jimmie Rodgers festival from scratch. This is a tremendously difficult thing to do. E.T. put in the effort to honor his idol. Jim Denny wasn’t simply setting up shop across the street with some healthy competition. He brought a free show to town on the same night with half the Grand Ole Opry lineup and several big names you would have had to buy a ticket to see on the Jimmie Rodgers event the previous night.

It’s hard not to see that as a giant middle finger.

Can you imagine what would happen if Coachella decided to start a festival 8 miles away from Bonnaroo, on the same weekend, for free?

It would crush Bonnaroo.

This was such a big deal that they didn’t even have the Jimmie Rodgers Memorial Festival the following year. They regrouped to put one on again in 1959 but Carrie Rodgers’ health had already taken a turn for the worse and Ernest Tubb was never involved with the festival again.

Mostly a kind man, E.T. was different when he’d been drinking. A beer or two while gambling with the guys, he’d be fine. It was the times when he’d get to drinking for a whole day or two… or five…

Mirrors would get smashed…

Windows broken…

He had a thing about glass, apparently.

Slap Iron

According to Billy Byrd, Ernest Tubb’s reaction to the Philip Morris Country Music Show undercutting the Jimmie Rodgers Memorial Festival was to get drunk and stay drunk for the better part of a week. They carted him back to Nashville but he was still drinking and he was still mad as hell at Jim Denny.

Finally, he called Denny at home in the middle of the night to cuss him out. Denny said something like, “Well, if you’re so mad about it then how about you just meet me down at WSM right now and we’ll settle things for good?!”

That sounded like a great plan to Ernest Tubb.

He strapped on a gun belt with bullets and a .357 magnum in the holster and drove downtown in his Cadillac, wearing his house slippers.

Meanwhile, when Jim Denny had hung up the phone, he simply took it back off the hook again so Ernest couldn’t call him anymore and then went back to sleep.

So, Ernest Tubb is drunk off his ass with a loaded gun when he stumbles into the lobby of the National Life Building where WSM was located. It’s close to 5:30 in the morning. People are starting to show up for work. There’s more than one version of what happened next.

The gun gets fired in all of them.

Bill Williams, the news director at WSM, says he was walking in to work when a gunshot rang out in the lobby and a bullet went over his head into the wall. He turned around, you know, pretty scared… and saw Ernest Tubb standing there in his house slippers with a revolver. When he asked Ernest what the hell he was doing, Ernest said, “My God, I’ve shot the wrong man!”

Whether or not he’d been actively trying to kill anyone, we’ll never know for certain. It seems to me like he thought he had successfully shot someone and was only upset that someone wasn’t Jim Denny. Either way, Ernest settled down after thinking he’d shot an innocent person. Bill Williams called his boss Jack DeWitt to tell him what happened. Jack told Bill to take Ernest home. He would have except the police had been called as soon as other employees heard a gunshot in the office building. Ernest Tubb went to jail for drunk and disorderly plus carrying the weapon.

It was mandatory to hold public intoxication arrestees for three hours, so Ernest bought cigarettes for all the other inmates and sang songs with them while Bill Williams waited to take him home.

$60 dollars bond got him out and that was the end of that.

Jim Denny’s name was kept out of the papers, though everyone in the business could read between the lines and see who Ernest had wanted to shoot.

The incident seems to have had no effect on Ernest’s career whatsoever. Apparently if all E.T. was trying to do was put a bullet in Jim Denny then that was fine. His career lasted into the 1980s. He was still doing over 200 dates on the road a year and he only quit in 1982 because of problems from his emphysema. In 1984, his lungs killed him, just like his hero Jimmie Rodgers.

The Midnite Jamboree still airs every Saturday night and you can still buy music from Ernest Tubb’s Record Shop.

We’re told that, in 1963, Ernest Tubb made up with Jim Denny before Jim passed away from cancer. The Jim Denny Artist Bureau stayed in business for only a few more years. Jim Denny was inducted to the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1966. Cedarwood, Jim Denny’s publishing company, was sold to Mel Tillis in 1983.

Ernest Tubb had been inducted to the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1965, while he was still alive.

Thank you for listening and reading. If you enjoyed this story, please share the podcast with a friend.

-TMC

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [with links to purchase or stream where available]:

- Dick DeBenedictis – “Matlock Theme” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ernest Tubb – “Tennessee Saturday Night” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jimmie Rodgers – “T for Texas” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ernest Tubb – “Waltz Across Texas” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ernest Tubb – “Married Man Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ernest Tubb – “Thanks a Lot” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Roy Acuff – “I’ll Forgive You But I Can’t Forget” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Just One More” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ernest Tubb – “Just One More” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ernest Tubb – “Walkin’ the Floor Over You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ernest Tubb – “Drivin’ Nails in My Coffin” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ernest Tubb – “I’ll Get Along Somehow” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ernest Tubb – “Slippin’ Around” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Excerpted Video

These live performances are all epic, which is why I used them in place of studio versions in the episode.

I have no idea if they’ll stay up on YouTube but here they are for now:

Commentary and Remaining Sources

Okay, first of all, if I didn’t make it clear – it is impossible to overstate Ernest Tubb’s importance to country music. Aside from influencing basically everyone who matters, he was one of the first (if not, in fact, the first) artist to bring an electric guitar player with him onto the Grand Ole Opry stage. If you want to call it “honky tonk” and it happened after Ernest Tubb, it was influenced by Ernest Tubb.

Before I get to the story, I’d like to address one thing.

In the 1980s, Clyde Moody tried to start an alternative association to the Country Music Hall of Fame called the Country Music Pioneer Association. The CMPA had a trashy newspaper that Clyde essentially used to rant against the industry and print whatever shitty rumors people sent him. Among these rumors was one that Ernest Tubb died broke and alone in a cheap downtown motel, shunned by the country music world he’d done so much to help.

This rumor is still spread as fact and I do not believe it’s true. Charlie Louvin even put it into his posthumous autobiography, which isn’t the only thing Charlie got wrong in that book…

First of all, the source was Ernest’s estranged wife. Next, Ernest died owning 70 percent of the Ernest Tubb Record Shop, which had multiple locations running and was very profitable at that time. He was not a broke man.

I believe Ernest chose to turn visitors away because he was wasting away of emphysema and didn’t want anyone who loved him to have that as their last memory of him. People would try to see him and he’d tell his son Justin to tell them thank you but he’d rather not have the company. The end.

Back to Ernest and Jim Denny.

The roots of country music are growing all over this story. You’ve got Jim Denny showing up right as the Grand Ole Opry is becoming a thing. Ernest Tubb gets in there and his throat is broken so he can’t do what he wanted to do his whole life, which is imitate his hero. His throat gets broken, he has to create this new thing and he ends up influencing Hank Williams Sr. and everyone…

It’s amazing. I love this story.

I won’t even try to pretend I remember the first time I heard this story. The story about Ernest Tubb going down to WSM early in the morning with a gun and firing off a round, that is. I’d always hear it brought up as an example of how wild and crazy those old school guys were, everybody laughs about Ernest being hauled off to jail and ultimately getting away with causing some trouble.

Nobody ever seemed to know why it happened and that’s all I ever really wanted to know.

Ronnie Pugh’s very well done biography on Ernest finally had most of the story for me. The book had the big Jimmie Rodgers Festival thing, why that affected Ernest so deeply, as well as the most detailed account of Bill Williams’ version of the lobby shooting. I went with Bill’s version because a) he was the news director of WSM with a reputation for being able to throw away the day’s script and ad lib the news without making a mistake and b) he was the one right in the middle of it, calling his boss at the station, going with Ernest to jail. (Shoutout to Jim Varney.) Everyone else seemed like a bystander trying to get their name involved. Like a security guard saying he told Ernest to put the gun away and Ernest fired the shot because of the guard basically daring him not to shoot the gun.

Also, I’m aware there are differing revisionist history-type opinions about how well Elvis Presley’s debut on the Opry did or didn’t go. He didn’t get an encore. Special guests almost always got an encore if they were good, so that settles it for me.

I’ve seen every year from 1924 to 1929 cited as the year of Denny being hired at WSM and/or their parent company. Not very important to me.

Let’s see, there was a biography of Johnny Cash that quoted a Rolling Stone interview with Johnny talking about Jim Denny making him wait outside his office for 2 hours.

Larry Jordan’s biography on Jim Reeves had a bunch of great information on the Jim Denny Opry Scandal.

I found a Billboard magazine from 1956 reporting that Philip Morris paid over $400,000 for the talent on that first package tour. That is a mind-boggling number in 1956. $400,000 for maybe ten acts.

Craig Havighurst wrote a book on the history of WSM, called Air Castle of the South, which is just a massive subject in itself, but there was great info there on what really happened with Denny’s firing. Pretty much everywhere else you get that story is from the artist side of things and none of them get it all the way right.

That clip of Justin Tubb talking and the clip of Johnny Paycheck were both from one of the Country Family Reunion DVDs, which are pretty much all amazing. Bill Anderson hosts the series, always with different old school people on there talking and telling stories. Any of the ones with Grandpa Jones or Jimmy Dickens on them are fucking hilarious.

And there’s a book called Andy and Don with that confirmation of Percy Foreman inspiring Matlock. Percy is no longer alive and his New York Times Obituary had some other bits. Like, Jack Ruby asked Foreman to defend him after shooting Lee Harvey Oswald but a communication error kept that from happening. Foreman did represent Martin Luther King Jr’s assassin James Earl Ray but only long enough to convince him to plead guilty.

Oh, yeah, The Texas Defense thing. Uh, I’ve spent a lot of time in Texas and this defense is so effective there that I went into this episode with the understanding that it’s actually a statute on the books. Like, people who’ve lived in Texas their whole lives believe they live in the state with a He Needed Killin’ Law. It was only after uncovering Percy Foreman that I learned it’s just a legal defense strategy that works incredibly well.

[Send questions about this episode or anything else to questions@cocaineandrhinestones.com and your question may be answered in a Q & A episode at the end of the first season. BONUS: Cocaine & Rhinestones Season 1 Q&A Episode! Please share this episode or blog post with one other person. You can share it with more than one person if you want but all I’m asking for is one. I’ve loved the time I spent on doing this but I’ve also had to sideline everything else in my life in order to make that time. If I’m going to keep doing this, there has to be an audience for it. Thank you. The next episode will be on Loretta Lynn’s song “The Pill” being banned from radio, why that happened, how it turned out and what it means.]