What do you do when an entire country misunderstands your song and turns it into one of the biggest hits of the year?

That doesn’t happen often.

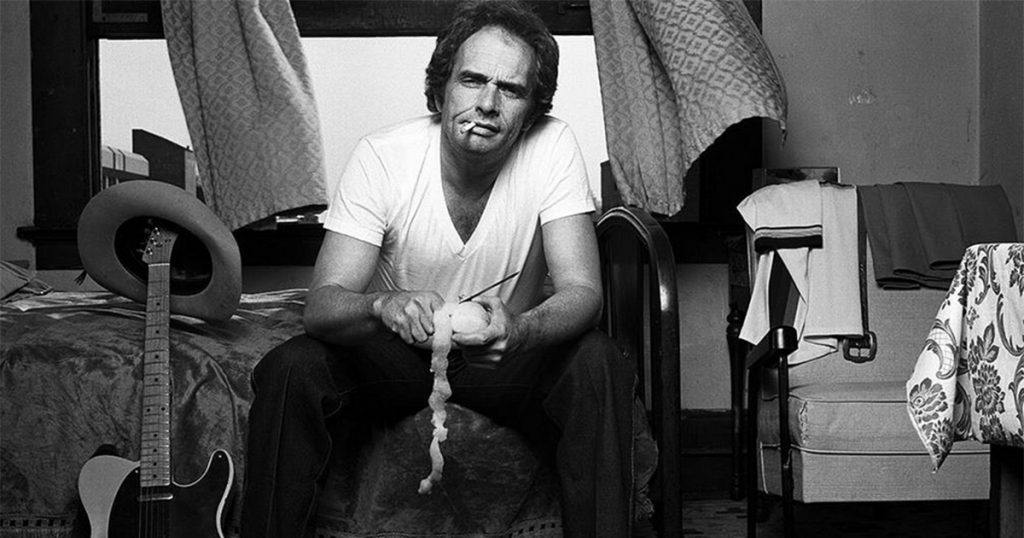

This episode looks at what Merle Haggard did when it happened to him in 1969 with “Okie from Muskogee.”

The song was just what so many Americans needed at the time. Conservatives needed someone to stand up and defend small town, traditional values. Politicians needed someone to justify America’s continuing involvement in the Vietnam War. Oklahomans needed someone to redeem the meaning of the word “okie,” a hateful slur that arose from The Great Depression.

The only thing is, Merle Haggard wasn’t doing any of those things when he wrote the song. Then what the exact hell was he doing, you ask?

Maybe things will become a little bit more clear once you know what Merle Haggard knew about Herbert Hoover, The Great Depression, The Dust Bowl, okies and satire. Maybe.

This episode is also recommended if you like: Gram Parsons, Ray Wylie Hubbard and the Revisionist History podcast.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

In addition to The Library, these books were used for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

Shut Up and Keep Singing

The popular understanding of “Okie from Muskogee” is that it’s a conservative anthem about the way America ought to be and how liberals are a bunch of whining pansies. This is what most conservative Americans think about the song and it’s what most liberal Americans think about the song.

They’re all wrong.

A lot of people think the country music singer-songwriter, Merle Haggard, and the character singing “Okie from Muskogee” are the same person. This is absolutely incorrect and that is not my opinion. It is a fact.

In February of 1970, Merle Haggard told a reporter, “We wrote it to be satirical, originally, but then people latched on to it and it really turned into this song that looked into the mindset of people so opposite of who and where we were.” He’s straight up telling us the song was written as a joke.

It’s not making fun of all liberals but it’s not making fun of all conservatives, either… I believe the butt of this joke is a very specific type of person who we’ve all met. But what do you do if you sing a joke to an entire country, they all think it’s serious and they can’t get enough of it?

You shut up and keep singing.

Now you need to know what Merle Haggard would have known about The Great Depression and The Dust Bowl.

The 31st President of The United States

Herbert Hoover attended Stanford University in its first year, despite failing every entrance exam except math. A professor admired the “strength of his will” and gave him a chance. Hoover didn’t waste it. Graduating in 1895 with a major in Geology, he was a retired multi-millionaire by the age of 40, his fortunes made in mining operations around the world. From Australia to China to Russia to Africa, the man knew how to run a mine and he made bank. In 1914, Hoover’s worth would be nearly $100,000,000 in 2017 money.

When World War I broke out, he was not only in a financial position to help out but early retirement gave him plenty of free time to organize relief efforts. First, he helped over 100,000 American citizens in Europe get back home safely. Then he got to work keeping millions of citizens in German-occupied Belgium from starving to death. This required Hoover to personally and independently negotiate with leaders of multiple countries at war with each other to arrange shipments of food through borders and make sure it really got to Belgian people instead of German soldiers. The Germans resented him for obvious reasons. British leaders, including Winston Churchill himself, also did not appreciate Hoover involving himself. Still, his efforts were successful. Pretty impressive for some rich guy with no political experience.

Fast forward to 1927.

Hoover’s back in the U.S. and he’s been appointed Secretary of Commerce under President Coolidge. Typically, that position would have no involvement in disaster relief but when the Mississippi River floods ten states, the governors of six of those states request Herbert Hoover’s direct oversight. Feeding half a million Americans left homeless by a flood should be a cakewalk compared to what he’d done in The Great War.

Hoover has to raise private money for the Red Cross because no federal funds will go to the cause. Hoover gets the money. The Red Cross is technically in charge but they’re more than happy to let Hoover call the shots from up top. His big idea is to send in the necessary supplies for volunteers from local communities to build their own shelter camps, leaving Red Cross personnel free to work on coordinating shipments of food, clothing, medicine and doctors.

Local Red Cross chapters will also be given some military resources to help round up survivors and get them safely into the shelter camps. You know… soldiers… with guns… taking instruction from community leaders in the South… in 1927…

Did I mention that at this point in history 75% of the Delta lowlands population was black and they performed 95% of the farm labor?

So those soldiers, under local direction, aren’t there so much to safely direct people to the camps where they can receive help, as they are to round up black men and force them at gunpoint to build the camps, then keep them there to carry the best relief supplies to the separate and much nicer camps for white people who performed little to none of this work. There is at least one documented case of a local white police officer murdering a black man who refused to be treated like a slave. The crimes against humanity here are lengthy and a matter of historical record. Feel free to look into it but make sure to check the source of whatever you read because Herbert Hoover went to great lengths to cover this up. If you see a report from the Colored Advisory Commission in the footnotes, that’s the product of a real dirty deal.

Hoover got news of how his Washington D.C. plan was playing out in Southern reality. He knew he could not let the rest of the country find out about it. See, all the goodwill he’d built up since World War I had him on the fast track to the Oval Office. Hoover met with leaders of the black community and told them he needed to form a committee to “investigate” these troubling rumors and draft “an official report” on the situation. Essentially, he’s gonna be the next President as long as everything looks good and if everything looks good (*wink wink*) then these black leaders will be given an unprecedented level of access to and important positions in his administration.

It worked.

The committee submitted a report that did detail how black men were being held captive, beaten and forced to work. However, the report also included a note suggesting that Hoover should “feel free to make any changes or additions that may seem desirable.” The head of the committee, a Mr. Robert Moton, would periodically go on the radio and advise black people to stay in the South because, “The white man of the South loves the negro. Many who have gone north have not found conditions as they had expected. There is less reason now for negroes to leave the South than ever before.”

Months later, in 1928, despite never having held elected office of any kind, Herbert Hoover wins the presidential election by a ridiculous margin. It’s not even close.

One of his campaign ads in The New York Times had suggested a promise of a chicken for every pot and a car in every backyard. This idea connected with lower income Americans because the post-war economy wasn’t doing so great. The value of pretty much everything related to agriculture had fallen immediately after the war’s end. With no enemy to fight, new technology invented for the war was turned toward farming machinery. Productivity went way up but human jobs became obsolete. The market ended up with way more supply than demand, causing prices to crash.

It does not help when Hoover takes office and pretty much tells everyone, “Great! Now go kill a chicken for your pot and buy a new car!” Americans don’t seem to have understood that Hoover believed their own hard work and determination would deliver on his promise of a chicken in every pot and a car in every backyard. He believes American citizens will carry the nation through any so-called recession. It certainly isn’t the government’s place to give any handouts. He goes so far as to block government proposals which would subsidize American farmers, giving them money for their undervalued crops.

By the way, the Colored Advisory Commission is not rewarded for their part in covering up the crimes of The Great Mississippi Flood. No positions in the President’s cabinet. No unprecedented access to his administration. Black survivors of the disaster move out of the South in large groups, taking their cheap field labor with them.

In 1929, the stock market crashes. Everyone looks around at what they own and tries to figure out how to hang on to it for as long as possible. Against the advice of over 1,000 economists, Hoover raises taxes on products from other countries. The idea is to make buying Made in America the more affordable option. The problem is, other countries return the favor, raising taxes on American product. Our import/export trade is cut in half.

Americans pull their cash out of banks. The banks look to farmers to repay their loans. Farmers can’t do that and the banks begin to fail. Businesses downsize. Millions of Americans lose their jobs and then become homeless.

The recession turns into The Great Depression.

Herbert Hoover, who’d begun his presidency with a constant presence in the media, hides from the spotlight, only coming out once in a while to stick to his philosophy that the American government isn’t responsible for bailing out its own citizens and we can all come out of this thing okay if you just pull yourselves out of it. Much of the nation feels abandoned.

When the 1932 election rolls around, Hoover’s campaign tour is swarmed with angry mobs of people who throw rotten food at him. Multiple assassination attempts are prevented by the Secret Service. Needless to say, Hoover is not re-elected.

Before leaving office, he does finally begin work on aid programs that would become part of Roosevelt’s New Deal but Herbert Hoover’s legacy had already been destroyed.

The Dust Bowl

Meanwhile, back at the ranch…

Farmers in the Great Plains of America didn’t realize that using all that modern machinery to prepare more land for crops had removed native species of deep-rooted grass which held soil together in times of drought. The 1930s bring times of drought. 100 million acres of land centered on the Oklahoma panhandle turn into a geological Dust Bowl. Parts of Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas and Oklahoma become home to dust storms of Biblical proportion.

Perhaps the worst day is April 14th, 1935. Black Sunday.

60 mile per hour winds gather up 300 million tons of soil into a mountain in the sky and throw it at towns full of the poorest people in America. They say the approaching storms look like tidal waves of land. One woman sees it coming and, believing it must be the actual beginning of Armageddon, considers murdering her own child as an act of mercy.

When the storm hits, you find yourself in a blizzard of dirt, darker than night. Children suffocate within shouting distance of their homes because they can’t see to find the way. All that dirt swirling around generates enough static electricity to knock two fully grown adults down if they try to grab each other for support. Blue sparks dance over metal like electric fire.

Those who manage to get inside find the dust just comes through any cracks in the walls or windows and it’s only a matter of time before it gets into your lungs, causing dust pneumonia. Woody Guthrie is in that storm and others like it, as you can hear in his song, “So Long, It’s Been Good to Know Yuh.”

“So long” because we’re all probably about to die. But also “so long” because if we don’t die then we should all get the hell out of here, right?

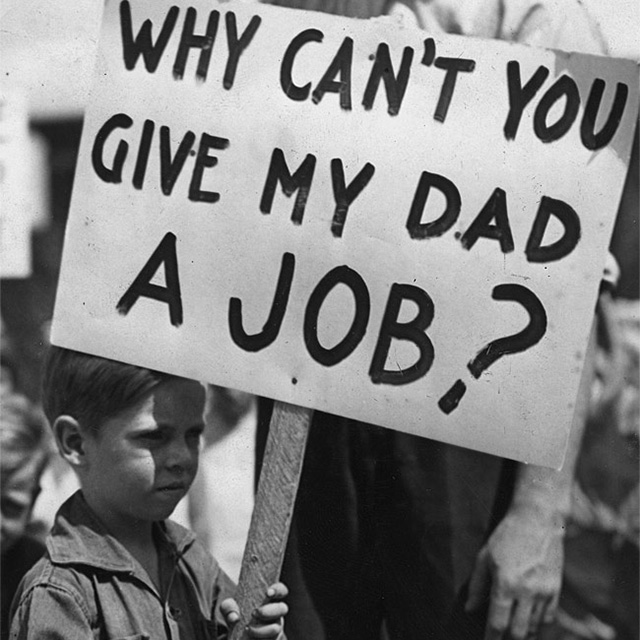

This entire country suffers under The Great Depression but The Dust Bowl is a living Hell. The nearest refuge is anywhere on the other side of the Rocky Mountains. A lot of people go that way and end up in California. Enough migrants arrive with sandblasted faces, no money and the word “Oklahoma” to answer the inevitable “where did you come from?!” that anyone who shows up hoping to find honest work while looking that poor starts being called an “okie,” even if they aren’t one of the ones from Oklahoma. It isn’t a term of endearment.

2.5 million people fled the Dust Bowl in the ’30s. Most of the ones who were able to find work found it in a field – unskilled labor. But California hadn’t been sitting there full of empty houses just waiting for families to move in. The biggest farms with the most work to offer ended up with shantytowns thrown together at the edge of the property. These shantytowns were sometimes called labor camps because anyone who had work to offer could drive by and get cheap labor. The camps were also known as Hoovervilles, named after the man most people blamed for this mess.

Migrants built tiny shacks out of scrap lumber and rusted metal – no electricity, no indoor plumbing. They got water from nearby irrigation ditches, which inevitably became contaminated with waste from poorly built outhouses, leading to constant disease and death in these camps. In more ways than one, shit rolls downhill.

This was a group of people who others in these hard times could and did look down on to feel better about their own circumstances.

“Times are hard but at least I’m not an Okie.”

“Get outta here, Okie. Go back to your camp where you belong.”

Signs in store windows read NO COLOREDS – NO OKIES. It was a hateful slur directed at the poorest of the poor – black, white, Native American, Mexican – all okies. Even after World War II pulled the economy out of The Great Depression, decades after the last Hooverville was bulldozed, “okie” remained a charged word. Say it the wrong way to the right person and you’d better have damn good health insurance.

These days all the electricity’s gone out of it, probably because of Merle Haggard.

Merle’s parents moved from Oklahoma to a Bakersfield apartment in 1934. His father, James, had a good job with the railroad in California. When a lady in the area asked if a railroad boxcar on her property could possibly be converted into a home, James bought the lot with that boxcar on it and expanded it into a 2-bedroom, 1-bath house with a kitchen. This wasn’t a shantytown shack. They had electricity and indoor plumbing. This is where Merle Haggard was born, in 1937, on land his father owned.

This isn’t an episode about Merle’s whole life, so I’m skipping a lot to get the part where he writes the song this episode is about. I’ll come back someday for the rest of it.

That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore

The story goes like this.

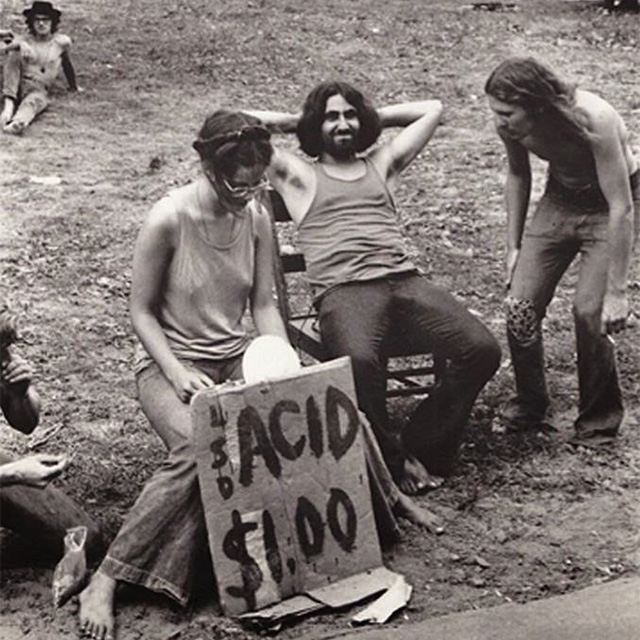

Merle and his band are riding down the highway in the tour bus. Some versions have a lit joint being passed around, which would explain why, when they pass a road sign showing how many miles they are from a town called Muskogee, one band member pipes up, “I bet they don’t smoke no marijuana in Muskogee!” If nobody on the bus is smoking at the time, that’s one hell of a non-sequitur. Either way, more one-liners follow and, in only a few minutes, Merle has a new song. His drummer, Eddie Burris, gets a cowrite credit.

Some nights later, they’ve got a pretty dead crowd in a North Carolina military town. The audience is full of Green Berets and, it doesn’t seem to matter what the band plays, everything gets the same reaction, which isn’t much. Merle decides to try out the new one. Three lines into the first verse, Merle sings about how “they don’t burn their draft cards down on Main Street” and every soldier in the place goes crazy.

You don’t need to know the story of how “Okie from Muskogee” was written to know that it’s a joke. There are clues everywhere in the words of the song.

We cannot begin to understand the genre of country music without understanding satire. Satire will almost always exaggerate some genuine aspect of its subject, in order to illustrate how silly that concept is when pushed to the extreme. If you can’t tell whether or not a song is satirical, start looking for contradictions in the logic of the characters. Like how the first two lines in the song are about the illegal drugs they don’t do in Muskogee, then, right after presenting the town courthouse with the American flag as twin symbols of patriotism, a line about about how much they love moonshine in Muskogee. If I’m not mistaken, making moonshine is still illegal in the entire state of Oklahoma and it was definitely illegal when this song came out. The lines about the courthouse and the American flag and the moonshine are brought back to end the song, so the entire song is literally framed in a philosophy that would be idiotically hypocritical if the person singing it really believed it.

We also learn how the people in Muskogee like “livin’ right and bein’ free.” Well, if there’s only a right way and a wrong way to live then what kind of freedom is that? If the right way to live includes breaking the law to make and enjoy moonshine then what is the right way to live, who decides what is the right way to live and what are we even talking about? There’s no answer because it’s ridiculous logic because it’s satire.

“Leather boots are still in style for manly footwear.” I’m sorry, manly footwear?! Who would ever say that with a straight face? It’s ridiculous. It’s satire.

But this is all irrelevant to what happened after the song came out. Every songwriter knows what you meant to write in a song does not matter. It’s what people hear that determines the meaning of a song. Soldiers heard a guy who sounded like he was saying, “Fuck everyone who burns their draft card!” People from Oklahoma heard best-selling country music artist Merle Haggard redefining the meaning of “0kie,” somehow associating pride with the word. And most everyone else heard Merle coming out as a hardcore Republican, a member of the so-called silent majority.

Merle Haggard vs. The Vietnam War

The single drops in September of 1969. That one line in the song about draft cards leads people in both political parties to treat it as a pro-war anthem. Some radio stations ban the song. You’d think a commercial for armed conflict would have more than a solitary, indirect line about war but, one reason people hear “Okie from Muskogee” as a patriotic call to arms is, Merle’s next single comes out only four months later and it’s called “Fightin’ Side of Me.”

This song, from beginning to end, specifically takes war protestors to task and a lot of what gets said about “Okie from Muskogee” after the fact is because it almost always gets lumped in with “Fightin’ Side of Me,” as if the two songs are the same song, saying the same things. When interviewers ask Merle to give his thoughts on both songs, he typically answers with a defense of the more severe “Fightin’ Side of Me” leaving everyone to assume that “Okie from Muskogee” is the same type of song.

It’s not.

Here are Merle’s comments when he’s asked only about “Okie from Muskogee.”

…the song actually said some things on behalf of the people who were rebelling against society, too. First of all, no one, I think, considered themselves a hippie. I think pride and patriotism were the things that actually sold the song and the rest of it was kinda immaterial. Lots of people didn’t listen past that point; lots of people confused the words or added words for their own benefit. – Merle Haggard

Compare that to when he’s asked only about “Fightin Side of Me.”

I’m not saying you can’t stand up and say what you believe in. That’s one of the most important rights we have and that’s what I’m doing. But I am saying – and I am attacking – anything that might destroy democracy. If we hadn’t defended our way of living, our American way of life, in the past – well, there wouldn’t be anything to tear up today. – Merle Haggard

Those are two very different answers for two very different songs. The further away from 1969 you get, the more likely you are to get the same answer from Merle when asking about either song. He focuses on the pride and patriotism each song made Americans feel and brushes the origin stories aside.

His real personal stance, then and always, seems not to be so much that he’s for the Vietnam War but that he’s against the methods people were using to protest. Whether you agree with him on that or not, consider the 1968 presidential election. Both the Democrat, Hubert Humphrey, and the Republican, Richard Nixon, campaigned on ending the Vietnam War. Many historians make the argument that it was more difficult for then-Vice President Humphrey to distance himself from President Johnson’s persistent escalation of the war effort. Nixon was better positioned to say he was against the war and he won the election. So not many people really thought the Vietnam war was still a good idea but Merle Haggard, apparently, didn’t think we should be fighting ourselves in the streets over it for all the world to see, especially since most of us agree with each other.

Something I haven’t mentioned and it may be possible you are not aware of: Merle Haggard is an ex-convict. He served time in prison. In prison, you take your friend’s side in an argument while you’re in public and wait until you get somewhere private to say, “You know you were wrong, right?”

Merle Haggard vs. Hippies

Possibly the only things Merle Haggard had in common with the narrator of “Okie from Muskogee” were patriotism and a genuine dislike of hippies. In May of 1970, calling hippies “barefooted bums,” he says he doesn’t understand where they came from and, “I don’t like their views on life, their filth, their visible self-disrespect. They don’t give a shit what they look like or what they smell like.”

He must have met a smart hippie after that because, a month later in June of 1970, he says, “Some of the hippies have good minds but I don’t believe in the filth and some of the other things they seem to represent sometimes. I’m not against long hair. I might decide to wear my hair long next week. I have nothing against long hair as long as there’s nothing growing in it.”

Keep in mind, “Okie from Muskogee” came out in September of 1969. The Manson murders had already happened but the general public had no clue who was responsible until several months later. So, the hippies in “Okie from Muskogee” are Woodstock/Haight-Ashbury hippies, not creepy crawl murder hippies. And Woodstock hippies weren’t only protesting the war. They seemed to be protesting the existence of western civilization.

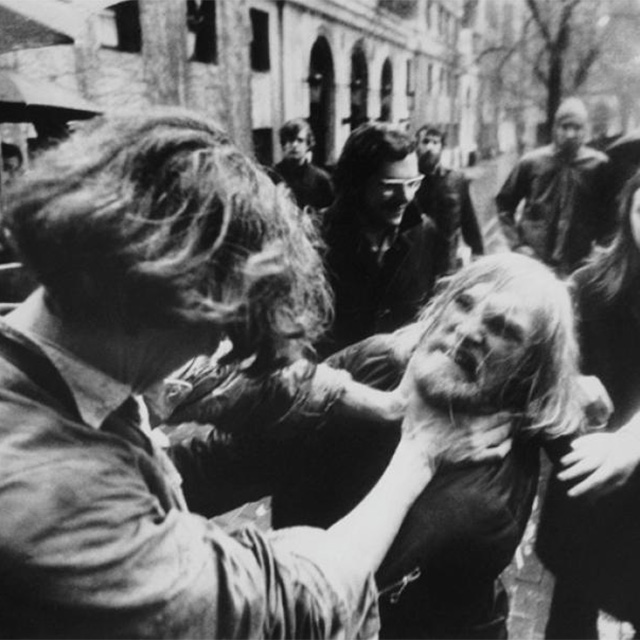

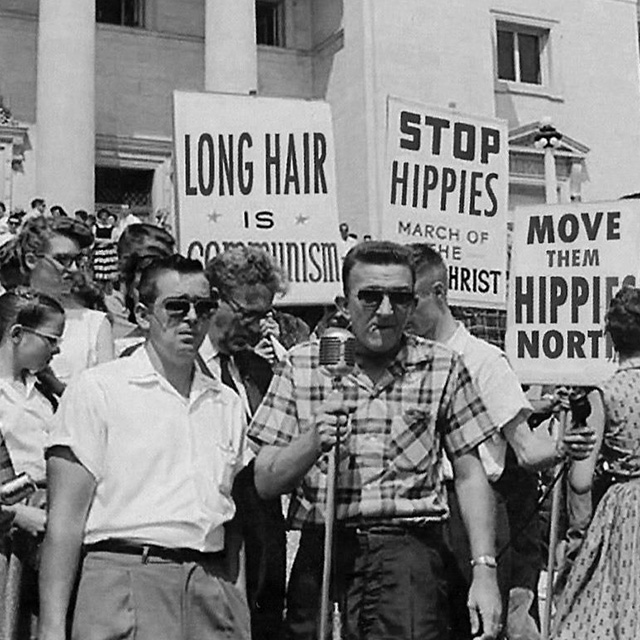

To many Americans, “turn on, tune in, drop out” looked like a bunch of self-indulgent assholes who simply didn’t want to take showers and get jobs like the rest of us. This pretty quickly became more than a conflict of ideas and Merle Haggard’s song was right in the middle of the violence.

Merle Haggard vs. Bigots

In her book I’m with the Band, Pamela de Barres remembers going to see The Flying Burrito Brothers at The Palomino Club. She specifically mentions this is during the point in time when “Okie from Muskogee” is the most popular song on the jukebox there and Gram Parsons can’t get through a show without audience members heckling him and calling him a “faggot” for having long hair. That’s a singer, onstage, at a nightclub in Hollywood. Out in the middle of America, looking like a hippie could get you beaten within an inch of your life.

A few years later, Ray Wylie Hubbard actually wrote his own song hinting at the place “Okie from Muskogee” held in this conflict. “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother” starts with the line “he was born in Oklahoma” and the “he” being described is one of these violent rednecks, mindlessly assaulting people who are different than him because that’s how his momma raised him. Haggard’s name is even mentioned in the song. It’s deeply ironic that not everyone who knows all the words to Ray’s song is in on his joke, either. Plenty of people to this day think his intention was to glorify “kicking hippies’ asses and raising hell.”

This is the most difficult thing for artists who work in satire. Not only do you run the risk of having the irony in your art misunderstood or taken wildly out of context but some of the people who take you seriously may belong to militant groups who engage in violence and hate crimes while holding up your work as a banner. They believe you’re the same as them. They think you would be proud of the things they do. If Merle Haggard wasn’t already aware of this and expecting it, he was made aware of it when George Wallace asked Merle to join his very racist 1970 campaign for governor of Alabama. Merle said “no” to Wallace and he told David Duke of the KKK to “fuck off” when David Duke tried buddying up to Merle.

Merle Haggard vs. The State of Oklahoma

Perhaps the most lasting impact of “Okie from Muskogee” has been the shift in meaning of the word “okie.” Even critics who understand the song was written as a joke mostly come up empty when it comes to explaining how the chorus could be a joke. How could Merle reconcile making fun of okies when the history of that word is so dark and so close to Merle’s family?

Well, I don’t believe he was making fun of okies.

Merle Haggard was proud of his roots. In 1970, he walked out on a taping of the Ed Sullivan show because they wanted him to sing “Surrey with a Fringe on Top” from the musical, Oklahoma. As far as I know, Merle never made fun of his Oklahoma heritage. His parents didn’t live in a labor camp and neither did Merle but he had an aunt and uncle who did live in a California labor camp and he’d go visit them sometimes as a child. He saw first-hand what the word “okie” meant. Why would Merle ever mock that?

That word isn’t the joke. I think “from Muskogee” is the joke. An “okie” from Muskogee is a contradiction, typical of satire.

The narrator of the song would only truly be an “okie” if and when they escaped The Dust Bowl during The Great Depression. They wouldn’t even need to be from Oklahoma to be branded an “okie” upon arrival. The narrator in the song is pretty clearly singing from a place of comfort “in Muskogee Oklahoma, USA.”

There are no okies in Muskogee.

To say it as directly as possible, and, of course, intending no offense, I think it’s quite likely that the line, “I’m proud to be an okie from Muskogee,” was poking fun at people in Oklahoma whose ancestors had never left the state but these people tried to wear the horror of those California labor camps as a badge of honor. We all know a person who identifies a little too much with the hardships or accomplishments of distant relatives. You know, “My great-great-great-great grandfather fought in the American Revolutionary War, so how dare you call me a coward?!” People do this with all sorts of things they have even less of a claim on – every guy you’ve ever met who always uses the word “we” when talking about his favorite football team, like he sits on the bench. Of course you’ll see the same thing with people who just happened to be born in the same state as some other group of people.

I’m imagining here a backstage scene at a concert in Oklahoma. Some annoying drunk guy from the area, feeling a little too familiar, puts his arm around Merle’s shoulders and says, “You know us okies gotta stick together.” Maybe Merle doesn’t say anything but something about it bothers him. It sticks with him. And, later, he realizes it’s because that guy wasn’t an okie at all. Merle saw okies.

Again, I’m only imagining that scene but if the chorus of this song isn’t a joke about that kind of person, then I’ll admit right now that I don’t have any idea what this song is about. But I don’t believe anyone else does either because, until this song became so phenomenally misunderstood, the word “okie” carried no pride with it. There’s no pride to be found when you’re slowly and senselessly dying in a Hooverville full of dysentery and starvation. The thought of being proud of that is insane.

If the song was just called “I’m Proud to Be an Okie,” none of the lyrics would take place in Oklahoma and it would be one of the darkest, most sarcastic songs you can imagine. Randy Newman would have retired after hearing it.

And I sometimes wonder what was going through Merle Haggard’s mind when the mayor of Muskogee made him an “Honorary Okie” in the middle of his concert there on October 10th, 1969. I mean, they made an album of the show, so you can hear the joke he cracks in the moment but I do wonder if he ever took a second to think about how absurd it was.

In any case, the chorus of the song, along with the rest of it, was largely taken at face value and, today, all “okie” means is a person from Oklahoma. That’s probably for the best.

Merle Haggard vs. His Fans

By the way, Merle Haggard did know the song would be taken seriously before he recorded one second of it. That first night he played it, when the soldiers went nuts over the “draft cards” line, he knew what caused that reaction but a song that can get a response like that from a crowd is hard to come by. You don’t put it on the shelf because some people will misunderstand it. Merle also had good reason to believe all public opinion wouldn’t be as one-sided and extreme as what a bunch of soldiers heard in the song.

“Okie from Muskogee” was by no stretch of the imagination Merle Haggard’s first hit. He had every reason to assume the public image he’d spent years building would help some people to get the joke. Merle’s first three #1 hits were all about the time he’d served in prison. His next #1 was about the outlaw antiheroes, Bonnie & Clyde. Another prison song with “Mama Tried” and then on to “Hungry Eyes,” about being poor in a labor camp despite working hard. Then, “Working Man Blues,” about working hard despite being tired of working hard. All #1 hits and every one of these songs could be viewed as anti-establishment, in one way or another.

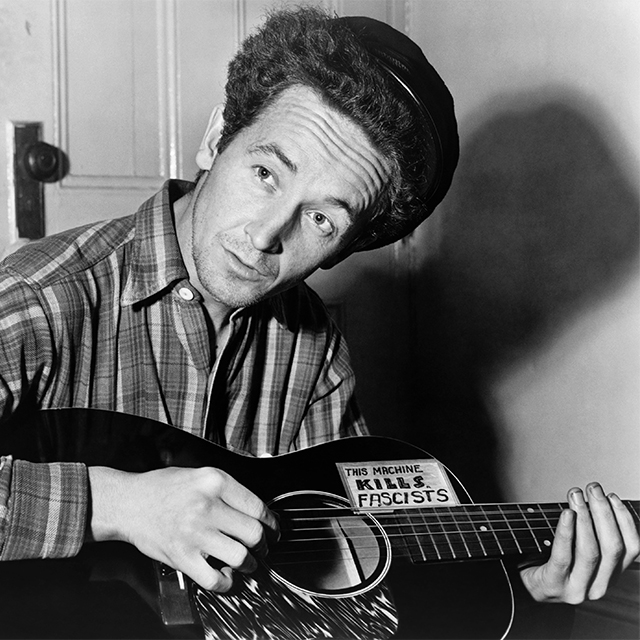

In the 1960s, the Arkansas prison system came under fire for some pretty extreme human rights violations. Investigation turned up cases of abuse and torture and quite a few unmarked graves on prison property. Merle spoke about this to the media as a human rights issue and many people thought they had an idea of who this Merle Haggard guy was. In 1969, Rolling Stone magazine praised Merle Haggard as a continuation of Woody Guthrie’s legacy. Woody Guthrie – the guy who had “THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS” written on his guitar… The guy who didn’t seem to care much whenever people would assume that he was a communist…

Then, “Okie from Muskogee” came out and fans wondered if they were wrong about Merle. Then, “Fightin’ Side of Me” came out and they were certain they’d been tricked. Many music critics and liberal fans forgot everything they knew about Merle Haggard because they felt betrayed. This was way worse than Bob Dylan going electric.

But Merle didn’t want to follow “Okie from Muskogee” with “Fightin’ Side of Me.”

Merle Haggard vs. Capitol Records

The song he wanted to put out as a single after “Okie from Muskogee” is called “Irma Jackson.” It’s another one sung from a narrator’s perspective. This time he starts out right away in first person, none of this royal “we” shit: I’d love to shout my feelin’s from a mountain high / An’ tell the world I love her and I will ’til I die / There’s no way the world will understand that love is color blind / That’s why Irma Jackson can’t be mine / I remember when no one cared about us bein’ friends / We were only children and it really didn’t matter then / But we grew up too quickly in a world that draws a line / Where they say Irma Jackson can’t be mine / If my lovin’ Irma Jackson is a sin / Then I don’t understand this crazy world we’re livin’ in / There’s a mighty wall between us standin’ high / But I’ll love Irma Jackson ’til I die

Irma is obviously not satire. Although doing a song about interracial love shouldn’t be confused as a statement by Merle Haggard in support of or condemning interracial love, anyone who takes “Okie from Muskogee” literally would have to do the same thing with “Irma Jackson.” In other words, a literal read on “Irma Jackson” doesn’t necessarily come out as a Civil Rights anthem but it does have Merle Haggard professing his undying love for a black woman. If nothing else, following “Okie from Muskogee” with “Irma Jackson” may have led a lot of people to understand that a song and the person singing the song are not always the same thing.

But Capitol Records had a little talk with Merle about “Irma Jackson.” I presume the words “career suicide” were mentioned and “Fightin’ Side of Me” came out as the next single.

Merle Haggard vs. Politics

There’s no doubt that it pained Merle Haggard to see his music politicized in ways he hadn’t intended.

In 1980, the writer Nat Hentoff reads to Merle this quote from a different writer, Peter Guralnick, “Merle Haggard has achieved more success than he ever intended and cannot come to terms with this success.”

Merle’s response?

That’s true. Success has its benefits and its holdbacks. There are just as many in either direction, you know. It’s no secret I’ve been in prison and I sometimes feel that all I’ve done since is just secured myself in a prison I can’t escape from. – Merle Haggard

He goes on to talk about the rule of show business every performer knows: play to the crowd in front of you.

Over the past year, I’ve come to accept it, give up to it and have fun when I can. Like, when we’re working, we can’t play everything we want to do. We have hardcore country fans in the audience and that cuts down on the jazz we can play some places. And sometimes you have to get loud and do the old country boy nightclub act. But, somehow or another, we get in enough to please ourselves. I guess I’ll stay in this prison. Where else would I go? – Merle Haggard

That’s why Merle sent his joke into the world knowing not everyone would laugh. That first crowd of Green Berets let him know he was holding a hotter hand than what he thought, so he played it. His record company pushed him to go all in with the next single, so he did. But after “Fightin’ Side of Me,” he backed off on the stuff that could be taken as anti-liberal until the 1980s. It’s possible that a bummer of a time performing at Nixon’s White House in 1973 made him realize playing music with political subject matter is nowhere near as much fun as playing music for the love of music. That upper class, Washington D.C. crowd sat there the whole show at The White House, cheered for “Okie from Muskogee,” the one song they knew, and then went back to not caring about country music for the rest of the night.

If you’re wondering about Merle Haggard’s real life politics, well, he says he never voted. My guess would be, like most people, he thought of himself as neither a Democrat nor a Republican, though he did write a song for Hillary Clinton’s 2008 primary campaign, which is the most he ever did for any politician, and we know he was definitely not on board the Trump train. Before he died, Merle told Rolling Stone magazine, “Trump’s not a politician. I don’t think he understands the way things work in Washington. I don’t think he realizes he can’t just tell somebody to do something and have it done.”

From 1966 to 1985, every single that Merle Haggard released went Top Ten Country and most of them went to #1. That adds up to 60 Top Ten singles in a row and Merle wrote most of the best ones himself. “Okie from Muskogee” came out three years in to maybe the most impressive career plateau in the history of country music singer songwriters. Whether you loved or hated the song, the simple truth is, it didn’t make or break Merle Haggard but it would be the biggest chapter in the book I would write about his music.

Oh, and Merle Haggard 100% smoked marijuana, though, maybe never in Muskogee.

Thank you for listening to and reading Cocaine & Rhinestones. Every episode is written and produced by me, Tyler Mahan Coe.

This episode is supported by drunkMall. Christmas is coming up and, if you’re like me, that pretty much just means stress. Money’s tight. Time is tight. Turns out you love way too many people and you’d like to get them a gift that’s at least memorable in the age of two-day shipping, where anyone can get anything they want sent right to their house. drunkMall.com is the answer. I should know, I made it. Go check it out but maybe not at work. Yeah, don’t go to the website at work or in public. It’s NSFW: drunkMall.com!

There are still nine more regular episodes after this of this first season and I want to thank everyone who’s helped me gain such a big audience for this show already. As always, I will ask that you share this episode or its companion blog post with just one person. If you know anyone who has ever expressed any kind of an opinion at all on the song “Okie from Muskogee” or Merle Haggard then they’ve just gotta hear this, right? I mean, there’s no way they knew all of this stuff. Unless you heard them saying exactly everything that I said in this episode, there’s something here that they’re gonna want to hear. So, share it, you know?

I’ve had some people ask why I’m only asking you to share it with one person instead of asking you to post it on Facebook or Twitter, like everyone else does. A few reasons. One, I have done a lot of work in marketing and I know that no one really gives a shit. Unless you have like a million followers, in which case, please do share my podcast. But, mostly, I really would like to think that there are people out there having real world conversations about this show. I think if you think of one person to share it with then it’s more likely that will happen and that makes me happy. So, that’s why I’m only asking for one person from you and thank you so much for doing it – really, sincerely.

Next week’s episode is about The Louvin Brothers, Charlie and Ira. This story is one that I knew I was going to tell as soon as I had the idea to start this podcast. It was almost my first episode. It’s got everything you could want. I don’t want to spoil anything but I’m pretty sure even people who think they already know this story are going to hear some things they’ve never heard before. If you’re not already subscribed to the show somewhere, make sure to subscribe so you can hear that as soon as it comes out. And, if you know a diehard Louvin Brothers fan, definitely go ahead and give them a heads up about it. They might want to catch up on the rest of the podcast before next week’s episode. Also, in this episode on “Okie from Muskogee,” I told you about how Capitol Records talked Merle Haggard out of releasing “Irma Jackson” next? Well, the specific person at Capitol Records who talked Merle out of it was a guy named Ken Nelson and next week you’re gonna hear a lot more about Ken Nelson. So, if you have fun connecting the dots between these episodes (like I do), you’re gonna love it.

Now, I said there are nine more regular episodes left of the first season…

If you want one more bonus episode at the end then here’s what you need to do: email me a question at questions@cocaineandrhinestones.com. If I get enough questions then I’ll do a Q & A episode to close out the first season. You can send me a question about anything you want – this episode, another episode, the show in general, questions about country music in general or anything else that isn’t even related to country music. If I can answer it, I’ll answer it. BONUS: Cocaine & Rhinestones Season 1 Q&A Episode!

-TMC

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [linked, if available]:

- Merle Haggard & The Strangers – “Okie from Muskogee” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Woody Guthrie – “So Long, It’s Been Good to Know Yuh” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Merle Haggard & The Strangers – “Fightin’ Side of Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Flying Burrito Bros. – “Sing Me Back Home” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ray Wylie Hubbard – “Redneck Mother” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Merle Haggard & The Strangers – “Irma Jackson” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Excerpted Video

These videos were either excerpted or referenced in this episode. They may be removed from YouTube in the future (for any of a number of reasons) but, for now, here they are:

Commentary and Remaining Sources

I’m really interested to see the response to this episode because this is a song everyone made their mind up about decades ago.

I did make sure to find a conservative website with an article written by a guy with a painfully obvious agenda to retain the song’s status as a conservative anthem and to paint Merle Haggard as a human individual who subscribes to strictly conservative political ideals. It’s not worth arguing against point by point when you’ve just heard what I think is the truth in this episode. I will say that it generally seems to me as if this writer is misrepresenting and omitting things as he sees fit to suit his purpose. Go read it, if you want. Make up your own mind, please, do.

How hilarious is it that Rolling Stone magazine was calling Merle Haggard the new Woody Guthrie less than a year before “Okie from Muskogee” came out and everyone did a hard 180?

I have seen so many people who think they’re so smart talk shit on this song without even coming close to comprehending it. Like Bill Maher, who went on TV and smugly attacked it as being a “country anthem from the hippie era that put the counterculture in its place.” It’s amazing to me how the dumb redneck songwriter was always smarter and funnier than the smart, funny TV guys…

There are a lot of musicians who got the joke (or at least seemed to get the joke) right when the song came out. Either that or they thought they were turning the song into a joke by embracing it, which is another possibility. Arlo Guthrie, Phil Ochs, The Grateful Dead and The Beach Boys all played the song at their shows. [Beach Boys live footage posted above.]

I do believe that Ray Wylie Hubbard knew that “Okie from Muskogee” was intended as satire. Even if not, he was absolutely a Merle Haggard fan. When Merle died, Ray Wylie told Lonestar Magazine, “You know the thing about Merle, he was known as a country artist but as far as songwriting, there’s kinda Merle and then there’s everybody else. When you mention songwriting he’s gonna be in the Top 5. Dylan, Gershwin, Willie, Townes… he’s in there. His legacy is unblemished and unequaled as far as songwriting goes. And, of course, being an entertainer, he wrote from a place that only the true poet knows. He wrote from a place that very few are aware of.”

Ray then goes on to tell the story of his opening up for Merle and being nervous about playing “Redneck Mother.”

And, obviously, Gram Parsons and The Flying Burrito Brothers were enormous Merle Haggard fans. There is something so deeply sad to me about that part of this episode. You’ve got Gram who, love him or hate him, his utter devotion to country music as a fan can not be called into question. Pamela des Barres also wrote about how she went over to some house where Gram was and, when she got there, he was crying while listening to George Jones. She wrote something like how she couldn’t imagine crying over a hillbilly with a flat-top haircut. So, Gram has this intensely emotional connection to this music – it means more to him than maybe anything else – and then you’ve got these other assholes who think the exact same music would make a great soundtrack to beating the shit out of Gram Parsons in the alley out back. That’s really upsetting to me.

It’s probably worth mentioning how many parodies of “Okie from Muskogee” there are. You’ve got “Asshole from El Paso” [written by Chinga Chavin, not Kinky Friedman], “Hippie from New York City,” “Nosha from Kenosha.” You know, this rhyming scheme is pretty nice. It’s almost like you would use it if you were trying to be funny or something…

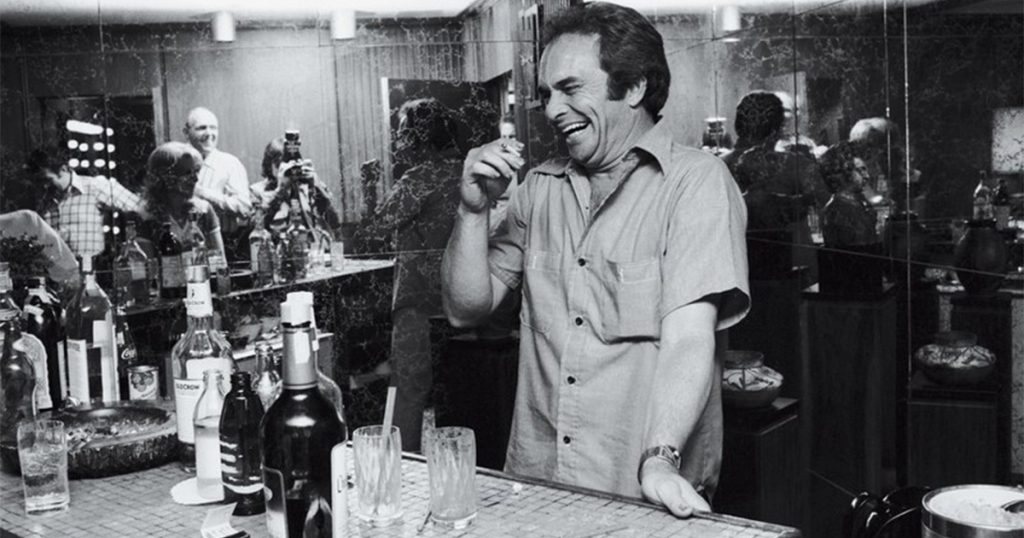

Nixon obviously didn’t end the Vietnam War as soon as he got in office but he did campaign on ending it. I was pretty surprised to find out that there is video of Merle playing that White House event. [Posted above.] It’s definitely worth watching. I wouldn’t want to presume to know what Merle is thinking but you can plainly see that something is really cracking him up for maybe twenty whole seconds around the 6:10 mark of the video. It honestly looks to me like he’s worried he might not be able to get through the song he’s laughing so hard and you can see how much of an effort he has to make to get himself back under control to finish the song. Plus, it’s worth watching to check out his awesome snakeskin boots. Manly footwear, indeed.

If any of you are economists or historians, I’m sure you’re well aware that I am not. As a matter of fact, I dropped out of high school but I don’t think I said anything controversial about Herbert Hoover or The Great Mississippi Flood or The Great Depression. There are different schools of thought about some of the cause-and-effect of this stuff and the relative importance of certain events but I went with what looked right to me.

I’m aware that, technically, Hoover himself did not place the campaign ad in the New York Times with the “chicken in every pot” line. It was placed by some “Republican committee” or something but, come on – it ran in the New York Times, he had to be aware of it, it’s not like he denounced it or issued a statement saying it was misrepresentative of his campaign.

There’s always going to be some of my opinion mixed into every episode of this show. That’s just unavoidable. I’m the one doing the research. I’m the one telling the story. This is all being filtered through me. All I can do is try to be careful with my language to point out when I’m giving an opinion or a fact. Please, feel free to disagree with my opinions. I honestly hope that some of you do because there’s nothing more boring than only talking to people who agree with you…

But, I really want to be clear about this: this episode is, I’m guessing, roughly 95% objective fact and, like, 5% my opinion. The chorus of the song is the only part of my analysis where I really see any room for disagreement about the original intention of the song.

You might ask, if I’m right about the chorus, then why didn’t Merle ever explain it in an interview? To which I would respond, a lot of artists hate spelling out the meaning of their work and we shouldn’t ever expect them to do that. But, also, why would Merle Haggard ever in his life tell a reporter that his intention was to make fun of millions of people who are now ride-or-die Merle Haggard fans. There’s no reason to do that.

There’s another Merle Haggard quote about “Okie from Muskogee” that I saved for right here: “It has so many different messages. It has messages that I didn’t even know were there.”

So, it’s not like reporters stopped asking him about it. He just always had a cagey response so he didn’t have to burst anyone’s bubble. (In my opinion.) Because that would have been a dick move.

For anyone who would like to say, for whatever reason, that the meaning of the word “okie” had shifted back to mean only a person from Oklahoma before this song came out, that is objectively untrue. The year before “Okie from Muskogee” came out, the governor of Oklahoma launched a PR campaign to try and make “okie” into a positive word. His political opponents (very expertly) ran a counter-campaign and the effort to change the meaning of the word okie was by all accounts a total failure. [1, 2] All evidence that I’ve seen points to Merle Haggard’s song changing the meaning of the word, which, I feel quite strongly, backs up my interpretation of the chorus. If “okie” had a positive meaning then, the year before the song came out, the governor of Oklahoma wouldn’t have launched a PR campaign to try to change it.

I would like to reiterate what I said in the episode: the misinterpretation of the chorus is for the best. Merle Haggard took a word that had a very negative meaning and completely changed it to mean something positive. Imagine if you could do that with other words that I’m sure we can all think of right now. Wouldn’t you do that? I would do that. There isn’t a single good reason for Merle Haggard to come out and say that’s not what he meant to do.

That crowd full of Green Berets that went crazy the first time Merle played the song? They didn’t just start yelling and clapping. They actually rushed the stage and Merle thought they were all coming up there to kick his ass. Once he realized they liked the song and wanted the band to play it again, that’s when I think he really started to figure out what he had accidentally done.

Alright, there are SO many books used as sources for this one. You wouldn’t think an episode on just one song would require a dozen books for sources but there is so much political understanding required to place this song into context and the song itself was the center of so much more political action. I really wanted to make sure I read as much as I could.

James N. Gregory wrote two books that I used. One is called American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California. The other is The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America. The titles of these are pretty self-descriptive but the one on okie culture in California, in particular, is very pertinent to the subject of country music. You don’t get Western Swing in California without that migration. You don’t get The Bakersfield Sound without Western Swing and so on. I’ve got a few more episodes coming up in this first season that will really dig in to how important California has been to country music and that’s because of okies.

Peter La Chapelle’s Proud to Be an Okie: Cultural Politics, Country Music and Migration to Southern California also covers a lot of this same ground.

Lanterns on the Levee: Recollections of a Planter’s Son is the autobiography of William Alexander Percy, which is where I got a lot of the information on the crimes against black people in The Great Mississippi Flood. And, if you think I found some super-liberal, alternate version of history: William was a white man, directly involved with carrying out the relief efforts of his friend, Herbert Hoover, and he says a lot of extremely white supremacist shit in this book.

Timothy Egan wrote a book called The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of The Great American Dust Bowl that is essential reading for anyone remotely interested in understanding this part of American history.

David Cantwell’s Merle Haggard: The Running Kind is an entire book that’s pretty much dedicated to unpacking the politics of Merle Haggard’s music, like I did here. If you enjoyed listening to this episode and you like to read books, I think it’s very safe to say that you would enjoy that book.

There’s a collection of Merle Haggard lyrics called Merle Haggard: Poet of the Common Man with an intro that gathered a lot of Merle Haggard interview quotes about the song. That was nice to have.

The quote where Merle is talking about getting out of prison and into another type of prison is from an interview with Nat Hentoff, which you can find in a collection of his writings, titled The Nat Hentoff Reader. Great journalist.

Paul Hempill, another great writer, has a piece on Merle Haggard in a huge compilation book called Stars of Country Music. If you enjoyed Paul’s book, The Nashville Sound (and I don’t see how you could not have enjoyed it), this is worth getting.

I already told you that Pamela des Barres’ I’m with the Band: Confessions of a Groupie was used as a source.

Wrong’s What I Do Best: Hard Country Music and Contemporary Culture by Barbara Ching is… Well, I don’t always agree with her interpretations of country lyrics and the meaning behind a song but her understanding and my understanding of this song are very similar, very similar. So if you thought this was cool, you might want to check that out.

Rednecks, Queers and Country Music by Nadine Hubbs was used for this episode and you’ll hear me mention it as a source for other episodes down the road, I’m sure. Nadine actually went on NPR [I keep calling these radio shows NPR on my podcast and then later realizing they aren’t. Full disclosure: I don’t listen to NPR, so if something sounds like NPR then I guess I assume that’s what it is.] a few weeks ago to talk about the assumptions people make about country music and its fans and how wrong a lot of these assumptions are. She talked about the “Irma Jackson” thing and I thought she did an amazing job. I checked out NPR’s tweets about the segment and there were so many people with terrible, knee-jerk reactions just to her saying that country music is not inherently racist. So, I’m really glad that she was willing to go into that place and say the things that she said to the people that she said it to. It’s extremely important for people to do that and I’m really proud of her for doing that.

The following books all spent some time on what “Okie from Muskogee” did to American politics and music in the late ’60s/early ’70s, with varying degrees of understanding for the song: Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks by Travis D. Stimeling, The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture by Bruce J. Schulman [This one’s pretty terrible, probably don’t buy it.] and Controversies of the Music Industry by Richard D. Barnet and Larry L. Burriss.

Okay, that is finally the end of these Liner Notes.

Thank you so much for enjoying this podcast about country music. I will be back next week to talk about The Louvin Brothers. Get ready, people.

“Sometimes I wish I hadn’t written Okie from Muskogee” – The Telegraph

Why “Okie from Muskogee” Was Merle Haggard’s Contradictory Masterpiece – Rolling Stone

The Pop Life: Riding the Country’s Wave of Patriotism – New York Times