[This episode of Cocaine & Rhinestones will be particularly upsetting for many of you. The details will not be as graphic as they have been in the past (such as in the Spade Cooley episode) but there are multiple instances of child abuse, child molestation and sexual assault in this episode. This was not what I expected to find when I chose today’s subject but, now that I’ve learned about it, I won’t pretend that it’s not there.]

Some people think we have all these “authenticity tests” in country music. We don’t. There’s only one test. Wynonna passed it. Then, everyone thought she’d cheated. The answers lie somewhere in her past…

From somehow surviving a childhood full of several types of abuse to a years-long reign over country music radio with her mother in The Judds, this path was not easy to travel and the end of it is only the beginning of another, much more treacherous road. Forget everything you think you remember. This isn’t a Lifetime movie. It’s rated R.

This episode is recommended for fans of: Harlan Howard, Merle Haggard, Charley Pride, Asleep at the Wheel, Ashley Judd, guns, dysfunctional families and liars.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

In addition to The Library, these books were used for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

The Only Test

You do not have to be born in a certain state to become a country music star. Hank Snow, Anne Murray and Shania Twain are all Canadian. If you’re not aware, Shania Twain is the single best-selling female artist in country music history. Being poor isn’t required to have artistic integrity in country music. If it was, then you’d never have heard the name “Gram Parsons” in relation to the genre. And, if you have no love for what Gram Parsons did with country music, then how do you feel about the songwriting of Townes van Zandt? His family was so rich they have a county in Texas named after them. Affluence is not a dealbreaker. You do not have to be white. Ask Freddy Fender, Neil McCoy, Charley Pride, Johnny Rodriguez or any other non-Anglo Saxon country superstar. I would go so far as to say there are no special circumstances of birth required to understand or create country music.

All you have to do is mean it.

Read Charley Pride’s autobiography. The racism you expect is there but, according to Charley, nearly none of it was the knee-jerk racism of white people not wanting a black person to make country music. It was almost entirely a secondary form of prejudice and it came from black people as well as white people. Everyone saw Charley Pride and made a snap judgement that he must be a failed R&B or Soul singer, putting on an act to try and make it in country music. (That’s, obviously, not what Charley was doing but that sort of thing did and still does happen.) Black singers and musicians were always telling Charley he could drop the act when there weren’t any white people around. Only, Charley wasn’t acting. Suspicious fans and country musicians would interrogate Charley before and after concerts to see if he was “for real.” They could see he wasn’t white, so that wasn’t the test he needed to pass. They weren’t asking him where he was from. They weren’t asking if he grew up poor. They wanted to know about his favorite singers and his favorite songs – what he liked, why he liked it, all the stuff music fans geek out over. Once they were satisfied it wasn’t a trick or an act, Charley was for real about this music, he was instantly accepted.

There’s a Hank Williams quote that fits here, “You ask what makes our kind of music successful. I’ll tell you. It can be explained in just one word: sincerity.”

Country music is a genre that deals with serious pain and sorrow, sometimes with gallows humor but often looking it square in the face. There’s a certain degree of trust that has to be there for that to work. You don’t have to play 200 shows a year for 10 years in Texas to be a great singer. You don’t have to work in a coal mine to know struggle. You don’t have to be poor to get your heart broken. But do you mean it? Because that’s the only test you have to pass. It’s an easy one to pass. All you have to do is be sincere. You can use a stage name, start wearing different clothes, have a toupee, get plastic surgery, create an entire alter-ego for yourself but you’d better mean it.

And: “Shouldn’t it just be about the music?”

Of course it should be about the music. It is about the music. It’s about keeping it honest. That’s why Charley Pride’s first records were shipped without the usual promo photo. That picture would have made it about the black man singing country songs, instead of being about the country songs sung by the black man. His team made the music more important by not shipping it with the backstory. Even though the backstory was amazing, it would have been a distraction from the honesty of the music. Because if we think we’re being sold a story or a gimmick or a lie, if that suspicion builds before an artist gains momentum, the music may never have a chance to get heard.

I didn’t know any of this when I was a child, in the ’80s, when I first heard Wynonna sing with her mother in The Judds. I didn’t know their label found a mother/daughter act with a seemingly legit backstory and a country music sound that was smooth enough to sell to pop audiences, while still being traditional enough to appeal to all these whining fans who say Nashville isn’t making real country anymore. I didn’t know any of that. I just thought The Judds were country music and I thought they were good. I still think both of those things. I remember The Judds breaking up and Wynonna coming out with an album of her own. There’s one single, in particular, that I remember very well. I thought that was country, too – and I guess I still do – but, listening to it now, I honestly could not tell you why.

If we’re going to try to understand Wynonna Judd, we have to try to understand her past, her family and, specifically, her mother. Since Naomi Judd, Wynonna Judd and her sister, Ashley, have all written at least one autobiography each, you’d think this would be easy…

Your Kentucky Girl

Naomi Judd’s real name is Diana but this is all going to be confusing enough anyway, so I’ll keep calling her Naomi. Born in Ashland, Kentucky, in 1946, her daddy owned a gas station. They weren’t rich and her father didn’t like to spend his money but they certainly weren’t poor. Decades later, Naomi would tell her daughters that she had a happy childhood. Her bedroom was kept clean. She got good grades. She saved her earnings from babysitting jobs to pay for her own tap dancing lessons. She was popular at school.

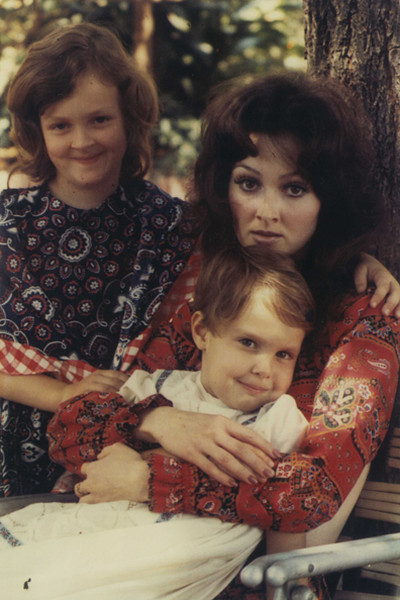

At 14, she began dating a 16-year-old boy, named Michael Ciminella. Michael was handsome and his family was well off. He had his own car to drive himself to and from the military academy he attended in Virginia. That meant he could take Naomi on dates to the movies or to the country club his family belonged to. Naomi liked that. For Michael’s part, well, just from looking at pictures, Naomi Judd had to be the most beautiful girl he’d ever seen in person. He proposed marriage on their first date. She, of course, said no. After graduation, Michael went to college for a year, socialized instead of studying, flunked out and came home. In Lexington, KY, a couple of hours away from Ashland, Michael found less distraction and maintained a 4.0 GPA. He and Naomi continued to date. When she became pregnant in 1963, at the age of 17, Michael again asked Naomi to marry him. This time, she said yes. When her parents learned she was pregnant, they freaked out. Naomi’s mother sent her to live with Michael’s family. Christina Ciminella was born in 1964. To keep it simple, I’ll be calling her Wynonna. After a year or two with the Ciminellas, Naomi and Baby Wy were able to move with Michael into a small apartment near his school.

After graduating college, Michael got a job that moved the family to California, where a second child, Ashley, was born. It’s in California that Naomi, for whatever reason, seems to begin hating Michael. From here on out, any house with the two of them living in it is the polar opposite of a happy home. Little Wynonna finds escape in visits to her Kentucky grandparents, the Ciminellas. She’ll fly back and be made to feel like the center of their universe – shopping for new clothes, endless treats and snacks, days in the country club swimming pool – much better than life at home, where Naomi goes full-tilt California: hippie ideals, anti-war protests, checking in and out of religions, from Theosophy all the way back to Baptism. She chops off all her hair into a pixie cut, similar to Mia Farrow’s in Rosemary’s Baby. In one of their last family photos taken before the inevitable divorce, Naomi looks like she should be a movie star. According to Wynonna, Naomi often talks of what their lives will be like after they make it, fantasizing aloud of becoming famous and rich. When little Ashley begins walking and talking, Michael nicknames her “Ashley Famous.” In spring of 1970, Naomi signs a lease on a two-story house off the Sunset Strip, forcing her family out of the valley and in to Hollywood. This fixes nothing between her and Michael. They argue more than ever. She starts smoking more pot. He sleeps on the couch more often. Wynonna is certain this is all her fault. Under the stress, in the L.A. smog, she contracts asthma and begins sleepwalking. For Naomi, moving her family to Hollywood is probably an attempt to break into show business. Within a year, she’s spending an inappropriate amount of time with a wannabe actor neighbor. In September of 1971, Naomi kicks Michael out of the house. She is now a single mother with no job and no car. She and her young daughters are about to find out what it’s like to live with a physically abusive man.

Wynonna remembers her mother taking any job she can get. Eventually acquiring a car, Naomi finds work as a secretary, a model, a game show contestant – whatever comes up, the closer to being in front of a camera, the better. Her image goes from that pixie haircut, miniskirt mod thing to a vampy red lipstick and Victorian blouses thing, then to an Appalachia-meets-American Indian blend of ankle-length tapestry skirts, turquoise jewelry and leather moccasins. Wynonna also remembers walking to West Hollywood Elementary and back, every day, often alone, down Sunset, past strip clubs and the Whiskey A Go-Go. She’s 7 years old with a house key that she wears on a necklace. One day, coming home from school, a man pulls his car up to the sidewalk and cruises along with her walking pace. He says some stuff, gets her to look down at his lap and he’s been jerking off the whole time he’s talking to her. She runs away screaming.

It’s around this time that wannabe actor neighbor moves in. He goes by the ridiculous name of James Dean Jr. (No credits on IMDB.) James sometimes makes lunch for the girls and babysits them. He also sometimes hits Naomi and knocks the girls around a little bit. There’s an incident where he throws Wynonna up a staircase. Again, she’s around 7 or 8 years old. Naomi eventually kicks James out. He moves into an apartment across the street and takes up some new hobbies, like leaving cheap wristwatches under a tire of her car so they’ll be smashed as Naomi leaves, letting him learn her weekly schedule. He also develops a taste for breaking into her home and attacking male visitors. Hobbies like that. The police have to get involved before it all stops. Michael Ciminella tried moving back in during all this but he and Naomi still couldn’t keep it together. It seems that Naomi truly despises him. She tells little Ashley that her father is a liar and a cheater, sometimes going so far as to say Michael tried to convince Naomi to abort Ashley. Other times, she tells Ashley that she was an accident of faulty birth control, a “foam baby.” Confronted with this lie in later years, Naomi will confess that Ashley had, in fact, been well planned. Here, in California, in the early ‘70s, Naomi insists Michael abandoned them all because he did not love them and that he refused to help out, financially. Michael later tells the girls he always wanted to be around and help out but Naomi would never let him. His job takes him to Chicago but he soon decides to quit and go country. Near the end of 1974, Michael moves into a rundown fishing shack that he calls Camp Wig. It’s on the Kentucky River, only heated by a wood burning stove but it does have indoor plumbing, which is a luxury for the area.

Tell Me ‘Bout the Good Old Days

Naomi wasn’t the only one who’d smoked pot in California. Michael had even dabbled in stronger psychedelics on the weekend with friends. He’d grown up in a country club family and married a woman who dragged him straight into Hollywood, the unofficial capital of materialism. Traveling that road brought one big headache after another, so maybe getting out of the rat race and away from the city lights is where he’ll find happiness.

With her dreams of fame not working out, Naomi sends the kids to live with Michael at Camp Wig and heads to Austin, Texas for a while. She gets into the music scene there, a bit, then heads up to Kentucky as well, having decided to become a nurse. Michael lets her move into Camp Wig. The beginning of 1975 finds the Ciminella family under one roof again. Both daughters’ memories of Camp Wig read like a commercial from the Kentucky Board of Tourism: their father catching fish or hunting up their dinner, spending days swimming in the river, jumping from a fence onto the backs of unsaddled horses to ride as far as they can before falling off, chasing fireflies at sunset through grass grown over their heads. This is where both girls remember music becoming a major part of their lives. Michael plays a little guitar. He has hippie friends out for parties and there’s always some album playing by Warren Zevon, The Rolling Stones or Joni Mitchell.

They’re living as if in deep poverty. When it’s hot, they sweat. When it’s cold, they shiver. When the river floods, they get scared. But, unlike the neighbors, they can leave anytime they want. The Ciminellas are slumming it. The constant fighting between Michael and Naomi, combined with a particularly bad instance of the river flooding, cause the adults to realize their time at Camp Wig must to come to an end. Michael moves to a place in town, where the girls live with him until the end of the school year. They sometimes visit Naomi for a weekend at her one-room bungalow in the nearby town of Berea, the Folk Arts and Crafts Capital of Kentucky. One of these mother/daughter weekends in Berea, driving somewhere during a rainstorm, Naomi sees an elderly woman slip off the curb into the street, clearly injuring her ankle. They circle back, get the woman to a hospital and wait around to take her home. Chatting during all of this, Naomi mentions her current situation, explaining they’d been out driving to look for a new place where she could live with her daughters. The next time Naomi checks her mail, there’s a letter, not from the woman she’d helped but one of that woman’s colleagues: Mrs. Allen, a music professor at Berea College. Mrs. Allen writes that she heard a nice young lady was looking for an affordable place to live with her two daughters. She gives a time and place for Naomi to come meet her with a little map of how to get there.

The next weekend, Naomi and the girls follow the map to a gated property and meet Mrs. Allen in the front yard of a two-story, four-bedroom house with hardwood floors, entirely furnished with antiques, a Steinway grand piano in the living room and a stone fireplace. There are berry bushes in the back yard. A huge picture window by the piano in the living room looks out onto an apple tree in the front yard. Mrs. Allen explains, this is her property and this is her house but she does not live in this house. She is a wealthy woman. This house, named Chanticleer, is just one of two houses on the property. She lives in the other. There are also some small cabins for a children’s music camp that Mrs. Allen hosts once a year. During the camp, students stay in the cabins and instructors stay at Chanticleer. The rest of the year it’s totally unoccupied. Seeing as how she doesn’t really need the money, Naomi and the girls can move into Chanticleer for, how does $100 a month sound?

Ashley is now about 7 years old and Wynonna around 11. Naomi, still in nursing school, often leaves her daughters to entertain themselves. Ashley creates a fantasy world for herself with fairies and imaginary friends. Wynonna wraps herself up in music. Naomi’s owned a guitar since receiving one as a going away gift in California. Michael taught Wynonna some chords at Camp Wig. Here, living on a college music professor’s property with a piano in her living room, Wy’s relationship with music moves beyond a childhood whim into something like fascination, an obsession. She’s listening to Emmylou Harris, Bill Monroe, Ralph Stanley and Doc Watson. The real stuff. Mrs. Allen gives her piano lessons but she’s far more interested in guitar, practicing for hours and hours on her own.

The elementary school in Berea is a bit of a drive from Chanticleer and Naomi has college classes that start very early, so everyone has to be up and in the car by 5:00 in the morning. Naomi drops the girls off at the house of some schoolmates. After school, the girls come back to this house to wait for Naomi to pick them up. Or not. Sometimes they just wander around town, unsupervised. You know, like how kids used to be able to do back in the good old days. Wynonna will walk down to the student center at the college to play pool. She’s apparently good enough to hustle $5 games from college students and go play pinball with the money. Sometimes she does this instead of going to school at all. Ashley, left similarly unattended, even though she’s only in first or second grade, is sexually molested by a man in Berea. The first adults she tells do not believe her, so she tells no other adults. She does not tell Naomi.

Despite spending most of her childhood living in close quarters with her mother and sister, Ashley sinks into isolation from an early age. Extreme isolation. Not out of some inherent introversion but because she feels she’s clearly not a priority, to her mother, maybe not to anyone around. These feelings are magnified by the increasingly codependent relationship between her mother and sister. Wynonna seems to have had a pretty healthy head start on becoming a typically histrionic teenager. Here at Chanticleer, her fights with Naomi are already intense and frequent. At the other end of the spectrum, their bonding sessions over music are equally intense – learning to play and sing songs together – bluegrass, Merle Haggard and Dolly Parton. Whether Naomi and Wynonna are fighting or practicing, Ashley is left on the sideline. Wynonna and Ashley do love each other dearly. After all, they’re the only ones around who know what it’s like to live with Naomi. But Ashley sometimes becomes the target of Wynonna’s wilder impulses. One of everyone’s favorite stories to tell is about what happened during the family’s move away from Chanticleer.

If You’ve Never Made It

First of all, you’re probably thinking a person would have to be entirely out of their mind to leave such an amazing house with such low rent. Well, according to Naomi, there was an unpleasant situation with a neighbor who broke into Chanticleer and stole some stuff. After the police interrogated the suspect, one of the family’s pet cats shows up murdered on the welcome mat outside their front door, traumatizing the girls and setting in to motion a chain of events that lead to her decision to leave Chanticleer. Neither daughter mentions a murdered pet. Ashley says they left Chanticleer because Naomi’s parents were getting a divorce and Naomi was being asked to testify on behalf of one against the other, so she ran away. Wynonna’s explanation is that’s just what Naomi does. She gets restless, packs up and leaves.

With her younger brother, Mark, to help drive, Naomi packs up a U-Haul and aims it at California. Wynonna and Ashley are put in the back of the truck. Naomi rigs the pulldown door to stay open a little bit, so the girls have “fresh air” back there, and they hit the road. If you’ve never made that drive from Kentucky to California, it’s long as hell. Wynonna, bored and pretty pissed off about having to leave Chanticleer, takes it out on the only person around: her little sister. She jumps on top of her and keeps licking her face until Ashley pees her pants. When she escapes, Ashley takes off her shirt, sticks it through that crack in the door and starts waving it around like a flag, hoping someone will rescue her. There just so happens to be a police officer behind them at the time, so Naomi gets pulled over for a lecture on how irresponsible it is to put small children in the back of a U-Haul, at all, let alone with heavy furniture and Wynonna gets a spanking from her Uncle Mark.

When they reach California, it’s back to the old way of doing things for a few years. Naomi and the girls cram in to a one-bedroom apartment next to a bar, then a duplex. During their music sessions, Naomi and Wy shut the bedroom door to keep Ashley from bothering them. Naomi gives little assignments – learn these lyrics or this chord progression by the next practice – and, if Wynonna doesn’t do it, Naomi calls her lazy and they fight. Michael Ciminella is entirely absent from these years, no cards, no letters. Though, he later insists that he did write and send checks, which were always cashed by Naomi.

At 14 years old, Wynonna finds a job cleaning tack in the stables of a nearby ranch. The radio there stays tuned to a local country station. She sings along with the hits of late ‘70s country radio while she works. One day, the station has a contest for some Merle Haggard tickets. She’s not the lucky caller but, Merle being one of her favorites, she tells Naomi she’ll save the money and buy the tickets herself, if they can go to the concert. Naomi agrees. Wy saves the money. They go to the show. Wynonna remembers them leaving Ashley at a friend’s house. Ashley remembers being left alone at home. Naomi only tells the first part of this story.

After pulling into the parking lot at the venue in Oakland, Naomi leans out her window, flashes a smile at the parking attendant and asks if it would be alright for her to park back by the busses. Oh, by the way, even though Naomi is living paycheck to paycheck and struggling to make ends meet, she drives a red ’57 Chevy with a personalized license plate that says RED HOT and she’d just put a set of whitewall tires on the thing. That’s the reason she gives the attendant for wanting to park by the busses instead of out in that crazy public parking lot. It works. And, wouldn’t you know it, Naomi and her daughter happen to be right there, dressed like movie stars from the 1940s, when Merle Haggard gets off the bus to walk his little dog, Tuffy. After speaking with them for a little while, Merle invites them onto the bus. This isn’t Naomi’s first brush with a famous musician. Back in Kentucky, she and her sister had met The Band one night. Levon Helm even took a liking to her, though Naomi insists she didn’t go back to his hotel room and that Levon was pretty upset about it. Here in Oakland, Merle suggests they watch the concert from the side of the stage instead of sitting out front. This is where Naomi’s version of the story ends.

Wynonna’s version has Merle making another suggestion after the concert. He suggests Naomi and her 14-year-old daughter join him on the bus for a few days. They go. Ashley remembers being left alone for days. RED HOT, Naomi’s beautiful ’57 Chevy that she needed to park near the busses so nobody would mess with it during the concert, stays where it is, sitting in that parking lot. Merle Haggard’s sons, Marty and Noel, are with him for Wynonna to make friends. She, of course, develops a powerful crush on Noel and, after a few days, mother and daughter fly home with a new favorite hobby. Turns out Naomi has a real talent for getting backstage at concerts. They get to see Emmylou Harris, Dolly Parton, Ricky Skaggs, Doc Watson, plus some non-country acts like Tower of Power and Huey Lewis & The News. Naomi’s drive to make music with her daughter kicks in to overdrive. She begins playing harmonica and making connections in the local music scene. After 4th grade, Ashley is sent to her Kentucky grandparents for the summer. At the end of that summer, Ashley is left in Kentucky and Naomi pulls Wynonna out of school so they can focus on music together. This is where Naomi stops going by Diana, the name she was given at birth, and starts going by Naomi. They get matching jackets with the words HILLBILLY WOMEN embroidered on them. They get on some very small shows in L.A. They move to Austin, Texas, just long enough for Naomi to date the harmonica player of Asleep at the Wheel and Wynonna to ditch her given name of Christina. She takes “Wynonna” from a Bobby Troup song Asleep at the Wheel plays, “Route 66.”

Back in Los Angeles, The Judds enter a talent show at The Palomino Club. They don’t win but Naomi meets a producer from Nashville who offers her a job with a show he’s got in Las Vegas. Despite this having nothing to do with The Judds as musical act, which is supposed to be the whole reason Wynonna isn’t in school, Naomi takes the gig. They move into a suite at The Aladdin. Wynonna spends her days playing guitar in the hotel room and rollerskating. Loretta Lynn’s doing a residency in the showroom, so, at night, Wynonna goes down to watch her perform. It all comes to a screeching halt when this Nashville guy’s production gets suddenly canceled. The type of suddenly canceled where Wynonna and Naomi are packing their bags as fast as they can to get out of the hotel before anyone starts asking questions about who’s paying bills. But that producer guy said he had connections in Nashville, so that’s the next move for The Judds.

The 100-Year-Old Farmhouse

This is near the end of 1979. Of course, that Nashville producer guy ends up being no help. Their first months in Nashville are spent living in cheap motel rooms or house-sitting for friends, if an opportunity comes up. Ashley is brought down from Kentucky before Naomi even has a place for them to live. The kid goes from spending a happy summer with her grandparents to sleeping in random houses and watching TV alone while her mom is out working. When Naomi finds a 100-year-old farmhouse for rent in Franklin, the family settles in to something resembling a routine. Ashley enters sixth grade and spends most of her time wishing she still lived with her grandparents. Wynonna enters 9th grade a year late and spirals deeper still into an unhealthy love/hate relationship with her mother. Naomi starts dating one of Elvis Presley’s old backup singers and the relationship sounds pretty intense. When things are good, he’ll come over and have loud sex with Naomi, the headboard banging against the wall shared by Ashley’s bedroom. When things are bad, Naomi steams open his mail while he’s on tour or secretly follows the tour bus for hours to see if he has any female company when he gets to a hotel. Sometimes he does. Once, Naomi gets so mad at him that she fires a .38 special over his head into the dining room wall.

After that, Wynonna sits there at dinner, staring at that bullet hole, trying to think of ways to keep Naomi happy with her. Getting better at singing and playing guitar is one thing that makes her happy but it isn’t always enough. Their arguments have evolved into full-blown fistfights, by the way. Someone usually calls the cops if Naomi starts acting like she’s going for her gun. Around 11 or 12 years old, when she’s at home alone, Ashley starts getting that gun out, holding it, thinking about what it might be like to shoot herself in the head with it. She writes a long letter to her grandparents about what life with Naomi is like but it never reaches its destination. After placing it in the mailbox, she sees that letter again, sitting on her mother’s dresser. Naomi tells her, “Don’t you ever talk bad about me to my daddy again.” It’s another 5 years before Ashley is able to escape and things get a lot worse for her before they get any better. But this is where we leave her until the ‘90s. On Wynonna’s first day of 9th grade, she’s a year older than the rest of the kids, dressed in her mother’s 1940’s Hollywood thrift shop dresses and driving that red ’57 Chevy. When she walks in, her classmates think she’s a teacher. But when you have a car in 9th grade, you make friends. It’s even better if you haven’t started drinking yet because you can be the DD, drive your friends around to parties, get into bars using fake IDs, all that fun stuff. Very nearly being raped at a party with some older kids, turns her off from that scene.

This whole time Naomi has never given up hustling for The Judds’ musical dreams. In 1980, she talks her way on to Ralph Emery’s early morning TV show. Ralph butchers their names, calling them something like Nairobi and Wyoming. He may have felt bad about that because he has them back on several more times, despite them, frankly, not being very good yet, as heard in one clip of one early appearance. [Posted below.] I could spend time picking it apart but the short version is, they aren’t singing harmonies so much as they are singing the same song, mostly at the same time, mostly on pitch. This is not the blood harmony of The Louvin Brothers. Still, good enough for morning TV.

These appearances give Wynonna some cool points at her school but nothing like, say, a popular cheerleader. Nothing like, say, Diana Maher, a popular cheerleader, one year ahead of Wynonna in school, daughter of Brent Maher, a producer for Dobie Gray, Ike & Tina Turner, Dave Loggins and Dottie West. Diana Maher watches The Judds on Ralph Emery’s morning shows but they don’t know about that until she’s in a bad car accident and taken to the hospital where Naomi works as a nurse. It’s there that Diana Maher tells Naomi she wants her father to hear The Judds. Naomi brings in a tape they’d recorded on a crappy little Kmart cassette recorder. Brent Maher is obviously far more concerned with his daughter’s recovery and whatever previous obligations were no doubt thrown off schedule by all of this but, some weeks later, he does eventually listen to that tape. Producers hear a lot of demo tapes. Great producers hear a lot more than what’s on the tape. Being a great producer, Brent hears potential. Not only that, he knows who The Judds need to work with to realize that potential, a man named Don Potter. Later, Wynonna Judd will single out Don Potter as being pivotal in The Judds making it and keeping “it” together once it was made. Jazz fans may recognize his name from guitar work with Chuck Mangione in the ’70s.

Don Potter

Brent Maher and Don Potter begin coming out to that 100-year-old farm house for long “practice” sessions. Essentially, they’re teaching what we think of as The Judds’ sound to The Judds. Now, of course, Wynonna and Naomi are the women who go in the studio and go on stage to perform this sound, so the the ability was always there. But it’s a lot more than ability that goes in to great musicianship, especially a vocal duet act. Don Potter’s great talent is as an arranger and, over time, he and Brent Maher arrange The Judds’ voices as they would any other pair of instruments – showing them both dynamics and restraint, how to create space in a song, when to leave it, when to fill it, how to stop singing simultaneously and start singing together, helping Wynonna unlock what she can really do with her voice. They do this for maybe a few months before Brent and Don realize that, nearly every moment they aren’t around, The Judd home is a war zone.

One of their big blowups nearly ends everything before it can begin. Naomi’s out on the road with that singer boyfriend of hers when a friend asks if Wynonna will drive them to Atlanta for a couple days. They don’t ask for permission or anything. They just take off in the crappy Honda Wynonna’s now driving. In Atlanta, the friend calls his parents to let them know what’s going on, they flip out and tell him he’s going to boarding school if he isn’t home by midnight. That kid’s headed home on an airplane when the brakes in the Honda go out. Wynonna is stuck in Atlanta. She hits up this singer she knows who says she can stay with him at his mom’s house. She calls Naomi to give her an update. Naomi tells her to not bother coming home because she’s done dealing with her. Then, shit gets weird. This singer in Atlanta who lives with his mom? He’s got problems. First thing, he’s supposed to be on psych meds but doesn’t always take them. Second, his mom seems pretty sure that The Lord delivered Wynonna unto them so she could quit trying to be a singer and start being her son’s girlfriend. Which leads us to the third problem, being the fact that this kid’s already been messing around with some girl who’s one of these psycho stalker obsessive types. Her near-nightly drive past the house lets her see Wynonna living there. This leads to some good, old-fashioned, white trash yelling matches in the front yard. Basically, Wynonna’s gone from a crazy home life to living in a full-tilt-boogie insane asylum and her mom told her to just stay there. But, also, Naomi’s version is that Wynonna stole money from her and ran away from home.

After about a month, Michael Ciminella’s father finds out about this situation. He immediately goes down there to get his granddaughter’s car fixed and help her get to Ocala, Florida, where Michael’s working on a horse farm. I’m not sure how long Wynonna stays in Florida but it’s long enough to cut her hair short and stop dying it red, long enough for Michael to talk her in to going to college. When she does call her mother to check in, Naomi says her boyfriend has a gig coming up in a hotel bar down there. Naomi’s throwing all Wy’s clothing in trash bags and sending it down with him. If she wants her stuff, she can go pick it up. Now, I haven’t been avoiding using this guy’s name for any weird reason. It’s just that right here is where he stops being relevant, after he talks Wynonna in to coming back to Nashville by reminding her she knows her place is onstage, performing. He tells her if she can’t make living with Naomi work, he’ll even help her get her own place. She goes home. Everything picks up where it left off.

Brent Maher

You might think Brent Maher and Don Potter, having spent well over a year developing this act, would be the ones to get them signed to a record deal. Nope. In June of 1982, Naomi meets a publicist, named Woody Bowles. Woody and his money man, Ken Stilts, become The Judds’ managers. The whole time Don and Brent are working on the music, Ken and Woody are out there trying to drum up interest in the backstory. Oh, and the music, too. But, really, their demo tape has been turned down all over town.

In spring of 1983, Curb Records takes the bait. Some small, independent record labels do middleman deals between artists and bigger labels. Curb is one of these labels. They’re not merely interested in The Judds. They see the potential for something big to happen, here, and they set up an audition with the head of RCA’s Nashville division. In-person is good for The Judds – great, even. Brent Maher, after hearing that crappy K-Mart tape, he’d gone over to their house to hear them in person and decide if he wanted to work with them; the 100-year-old farmhouse in Franklin, where Naomi made her own soap, where the back porch had a wringer washer for doing the laundry. Wynonna has always been very public about Naomi playing up the poor country girl act any time she wanted to really push it over the edge, laying on that Southern accent way thicker than it usually was. Get Naomi in a room and you’ll see the same southern charm that used to get them backstage in California.

Dreamchasers

At the RCA audition, Naomi delivers the backstory and they perform two songs, one Naomi wrote, called “Change of Heart,” and a song Kenny O’Dell wrote for them, called “Mama, He’s Crazy.” That gets ‘em signed. They hit the studio with Don and Brent to cut a six song EP and they’re sent to what Wynonna calls “media school.” If you’ve ever seen a stereotypically moody teenager listen to their parents talk, you can imagine why The Judds need to be sent to media school. Naomi will launch into some story she’s told a hundred times and Wynonna’s eyes about roll out of their sockets. If Naomi starts getting too far away from the truth or leaning too hard on that accent, Wynonna’s liable to call her out right there, even if they’re on TV. Here, in a post-Kardashian world, you’re probably thinking “so what?” In the early 1980s, country music audiences will not stand for a child disrespecting her mother that way. RCA doesn’t want these two to meet the world until Wynonna can reel it in a bit.

And it’s not like this record deal has magically repaired the mother/daughter relationship. If anything, now they have more to argue about. Like how Naomi thinks their outfits should always match and Wynonna wants to dress differently to express her individuality. Keep in mind, on top of the dysfunctional relationship with her mother, Wynonna is dealing with all the usual bullshit that comes with being a young woman in her late teens – insecurity, anxiety, body dysmorphia, the early stages of an eating disorder. This is not an armchair diagnosis from me. She’s been open about all of this. Try to remember how terrible you felt about, oh, pretty much everything when you were a teenager. Now, imagine feeling like that on national television or radio, while sitting next to your mother, who drives you absolutely out of your mind. Now, add in the fact that it’s an exceptional day when someone doesn’t ask, “So which one is supposed to be the mother and which one is the daughter?” Add in the fact that Naomi is still so young and petite that people are not joking when they ask that question; some people think they’re lying about being mother and daughter. Not fun for a teenage girl. Five months after signing the contract with RCA, Wynonna moves out of Naomi’s house and into the house of one of their managers.

In November of 1983, the first Judds single comes out on RCA/Curb. The song was written by Dennis Linde and the original recording of it was in 1975 by the ’50s superstar, Teresa Brewer. That arrangement was like a blend between Jimmy Reed-style blues and choir gospel. In 1976, Elvis Presley covered it, in sort of a post-Stevie Wonder rockabilly style. It’s important to note these points because the whole vibe that Brent Maher and Don Potter came up with for The Judds is like “these girls love white people blues and white people rock and they’re from Kentucky so it all sounds country.” Primarily using acoustic instruments, like guitar and dobro, is a conscious decision to keep things sounding smooth and laid back. Naomi would even call this The Judds’ Rule Number 3: acoustic guitars only. Their version of “Had a Dream (For the Heart)” opens with a barely-there acoustic guitar and nothing else but Wynonna’s voice taking a little pre-run stretch for the first 20 seconds, then a solo lap around the first chorus. It’s immediately clear who’s pulling the weight in this act. It’s also clear that the time with Don and Brent was very well spent when Naomi comes in on the verse, in sync and on pitch. So, this first single comes out with its gentle boogie woogie feel and it goes to #17 on country charts. That’s a hit. It’s also the worst performance in America of any Judds single released from here until their breakup announcement in 1991. Only three of their next seventeen singles will fail to hit #1 and those three are still Top Tens. Some people will say The Judds owe that streak to how they were promoted, which I’m about to get into, but I don’t think that’s any more true for them than it is for everyone else. The Judds were sent into the same gauntlet as every new major label artist in the early ’80s: the promo tour.

We all know what it means when a band goes on tour. They either just put out an album or they’re a legacy act (like The Rolling Stones) who doesn’t have to put out albums. They hit the road to hopefully make a bunch of money playing music for a bunch of people in different cities. A promo tour is just like that except, instead of playing concerts to audiences, the band is playing to the media. Playing music but, also, playing nice. You can see a clear example of promo tours at work in the modern movie industry by watching network television for a week or two. You’ll see the same actor pop up on several different talk shows because that actor is on a promo tour. They do those shows and they book hotel suites where all the website journalists come take turns interviewing them. That’s part of what a promo tour looks like for actors in 2018. The 1980s version of this, for musicians, meant going around the country to get interviewed and play a song or two on-air at just about every major radio station. You’d also hang out with all the station employees, sign autographs, take pictures, maybe do a private performance just for them, every bit of that. Then you’d spend the evening schmoozing in a hotel suite party or a rented out bar with the real power players – radio programmers, sales and promo reps, big shots from your record label’s local office. Get back up the next day, go to a new city and you do it all over again. That’s what The Judds do for nearly a year following the release of their first single and continuing into promoting their second single, “Mama, He’s Crazy.”

The song that helped them get signed to RCA is released as a single in April of 1984. By August, it’s their first #1, the first of fourteen #1s in a row. This and their next single both win Grammy Awards. The day “Mama, He’s Crazy” goes #1, Naomi, quits her job at the hospital. She’s 38 years old. Wynonna is 20. It’s around this time that The Judds play their first concert, opening for The Statler Brothers in Nebraska. Yes, you read that correctly. It’s around the time of their second single becoming their first #1 (a month before it went #1, to be precise), that The Judds play their first concert. We’re so used to hearing about bands playing dozens, if not hundreds, of shows before they ever even get noticed by a label that we come to think of that as the legitimate way to work your way up to making great albums. Anyone who doesn’t spend years sweating it out in crappy little venues hasn’t paid their dues. But that’s like saying you need to be a demolition derby champion in order to be able to properly drive yourself to the grocery store. Playing shows and making albums are entirely separate things. Playing a lot of shows can make you a great performer, it’s guaranteed to make you a much better musician and it’s one path you can take to making great albums. But you can learn everything you need to know to make great albums without playing a single concert, especially if your teachers are a world class producer and musician, like Brent Maher and Don Potter. The Judds learned how to make great albums straight from people who make great albums. Then, they made great albums. It’s that simple.

A Cyclical Fashion

Topping their initial hit with a #1 single from that same first batch of songs was enough to let the label know they had something big. The Judds were sent back in the studio to record a full-length album, Why Not Me. If we’re still worried about street cred, here, the title track was written to order by Sonny Throckmorton and Harlan Howard. Brent Maher almost always split The Judds’ albums evenly between five sleepy lullaby-type songs and five mid-tempo grooves. He needed one more of those mid-tempo grooves. He called Harlan on a Sunday, which Harlan had planned to spend fishing but Brent bribed him with some self-tied fishing lures. Harlan wanted those lures but he actually didn’t have any songs at the moment, so he suggested bringing in Throckmorton. Sonny’d been working on this melody for a while and he had a title: “How ‘Bout Me.” Well, Harlan had recently heard a different song called “How About Me,” so he changed the title and here’s him explaining the rest in a later interview:

“Why Not Me” wasn’t a great title and “What About Me” wasn’t either. To get a really good record, you’ve got to write a hell of a song when you’re dealing with a title that average. The only thing I know to do with songs like “Why Not Me” and “Busted,” which I never thought was a good title, is to put the title in there so often that people remember it. The weaker the title, the more you gotta hear it.” –Harland Howard

The finished product becomes the lead-off single and, if you don’t like it, then you don’t like The Judds because this is the sound of them hitting their stride. In the verses, right before she does the thing Harlan talked about by repeating the name of the song, the younger Kentucky girl makes sure you’re paying attention by abruptly throwing her voice higher at the end of every setup line. You can also listen under Don Potter’s excellent guitar playing for the “laid-back” sound of the keyboard player slapping the back of an acoustic guitar, in place of a snare drum. With verses that strong, a chorus is just followthrough. The single comes out in September of 1984, the full-length in October and The Judds are on the road in a tour bus.

Friends, if you know any two people with a talent for not getting along, putting them together in a tour bus for any stretch of time? Not a great idea. The first bus The Judds buy is a Silver Eagle. That’s a 45 foot long vehicle, max, and it could have been 40, even 35 feet. Not very much room at all. There’s the usual couch/kitchenette/dining table in the front but, instead of one suite at the back of the bus, they have two. The only way to get to the suite all the way at the back is through the first one and the doors don’t lock. Naomi gets the suite all the way to the back of the bus and Wynonna doesn’t get even the illusion of privacy. In hotels, she and Naomi are always given adjoining rooms. This is not how young people become self-sufficient adults and it doesn’t seem that Wynonna was ever treated as one. If there’s an award show or televised performance coming up, Naomi chooses an outfit that looks good on her and Wynonna’s clothes are coordinated around that. Management decisions are made between Naomi and Ken Stilts, The Judds’ sole manager after he bought out Woody Bowles in 1986. Wynonna is rarely asked for input, often simply told what to do after the fact. Her voice may dominate their music but Naomi dominates everything else. This daughter begins to feel like an employee of this mother. And you may say, “So what? The family business is turning everyone into millionaires.” Yeah. But something about being raised with the illusion of poverty and an always-there safety net of well-off grandparents by a mother who drives a fancy car with vanity plates when the fridge is empty and you’re supposedly broke and then being left out of practically every decision or even discussion involving finances… Well, let’s just say Wynonna’s understanding of and respect for money may not be very strong.

When The Judds go to New York City, after making it big, right before Christmas, Wynonna and her first credit cards rack up thousands of dollars worth of presents. Ken Stilts takes her credit cards away and cuts them up. This legal adult with no personal space and no autonomy lashes out. One night, after performing near a college, she’s invited to a party and she goes. When she finally returns to the venue, all the busses and semi-trucks are loaded up, ready to go, parked in a line behind Wynonna and Naomi’s bus; everyone just waiting on her so they can drive all night to the next town and do their jobs. Make no mistake, this is wildly unprofessional behavior. If I was anyone in that crew, facing an all-night drive, I’d be pissed off at this kid and you would, too. But we have no reason to expect her to know any better, until now, until she sees all these people waiting on her like that and realizes her behavior now impacts the lives of so many others besides Naomi, who is, naturally, irate.

Codependent relationships usually play out in a cyclical fashion. You could sum this one up as: Naomi inevitably expresses displeasure with something Wynonna’s done. Wynonna, desperately needing to please Naomi, bottles up her feelings of inadequacy to do so until she eventually lashes out. They make peace. Rinse and repeat.

The Judds could never have had nearly a decade of #1 singles without Wynonna’s voice but her talent means nothing without Naomi’s satisfaction. When U2’s Joshua Tree tour stops through Tennessee and Wynonna joins them onstage without Naomi, that may have given her some confidence. Getting her own apartment in Nashville and dating Dwight Yoakam for a year during his mid-’80s breakout stardom, that may have given her some independence. Moving to a secluded log cabin outside Franklin, TN, that may have given her an even stronger feeling of independence. But, for the codependent child, independence soon becomes isolation. In the year 1990, when Naomi learns she has Hepatitis C and will have to quit touring, you may as well have drop Wynonna off on a desert island. It was only at the very end of the ’80s that Hepatitis C was confirmed to exist, so this diagnosis itself, in January of 1990, doesn’t initially look like the giant stop sign that it really is. But Naomi’s condition rapidly deteriorates. By July, with several canceled shows behind them, reality has sunk in. When Wynonna’s finally told Naomi is too sick to continue with The Judds, she says she feels like she’s the one dying. An October press conference at the record label, one month after the release of their final album, updates the world on Naomi’s illness. Behind the scenes, attention is split between planning The Judds’ Farewell Tour and the launch of Wynonna as a solo artist.

The Farewell Tour stretches from February of 1991 until December. They play 116 cities, which sounds like a lot for someone who has to retire due to an illness but Ken Stilts keeps adding dates to make sure they get everything they can out of this final tour. The last show is made available as a pay-per-view television event. The tour grosses 21 million dollars. One of their opening acts is a kid named Garth Brooks. Naomi probably doesn’t have to be talked into any of this, by the way. She clearly doesn’t want to let go and this could be her last chance to soak up the adoration from their fans. That does not, however, keep her from growing weaker. Her daughter now has to help her get ready for the show, doing her hair, getting her dressed. Under the stage lights, it’s all smiling and waving and singing. Back in their connected bedroom suites on the bus, there’s a lot of crying. Naomi says things like she’s bought funeral plots for the entire family so they can all be together forever; she’s gone out and bought a ton of Christmas presents for her future grandchildren, in case she won’t be around to spoil them. So, this is where Wynonna Judd is at, mentally, as her solo career is being planned, not by her but for her.

If you expect Ken Stilts or anyone else to now start including Wynonna in the decisions Naomi was making before, that’s not what happens. They just start making decisions themselves. Such as the decision to drop her last name and have her be known as simply Wynonna, like Madonna or Prince. (This is, ostensibly, to keep her albums from being put with The Judds’ albums in store racks, to give her a separate identity.) And the decision to move from RCA to MCA Nashville, home of Reba McEntire and George Strait, where Wynonna will be produced by the label’s president, Tony Brown, rather than the only producer she’s ever worked with, Brent Maher. These are big decisions for an artist to not be involved in but Wynonna may not even be aware that she has the option to be involved. She never was when Naomi made the decisions so the only thing that changes here is, well, nothing. She’s never known things like how much money is made or what the expenses are per show. She doesn’t even know how much money she’s worth. They put money in her checking account, she goes where they tell her to go and sings when they tell her to sing. That’s how it’s been with The Judds and that’s how we’re rolling into her solo career. But let’s talk about some of The Judds’ biggest hits, so we’re all on the same page with the musical changes that are coming.

There were two more hits on that first album. “Girls Night Out,” a feel-good party anthem for the ladies, rocking out about as much as you can with acoustic guitars. Then, “Love Is Alive,” a song so gentle you could put a baby to sleep with it. Their next album, Rockin’ with the Rhythm, kicked off with the single, “Have Mercy” – slow-motion rockabilly meets boogie bass and piano. Then, ethereal lullaby prettiness for, “Grandpa, Tell Me Bout the Good Old Days.” And, now we’re wide awake again for the title track, “Rocking with the Rhythm of the Rain.” You should be sensing a pattern, here. I mentioned it earlier but Brent Maher always tried to evenly split Judds albums between upbeat and downtempo songs. I’m just going through some singles but if you listen to the full albums, the vibe practically alternates track by track. In the interest of time, I’m going to skip to the title track of their last album, “Love Can Build a Bridge.” It’s sort of their “We Are the World.” It was used by several charities but take away the gospel choir and it’s the same basic formula as always. Despite The Judds’ Rule #3, they did use electric guitar on some songs, even bringing Mark Knopfler from Dire Straits and Carl Perkins into the studio to play on the River of Time album. None of this electric guitar work was ever anything that would rile the feathers of country music fans.

Wynonna…

Okay, now, Wynonna’s first single, which went #1 on country charts and #25 adult contemporary is “She Is His Only Need.” Check it out and I think you’ll agree, it sounds like The Judds’ downtempo stuff, right? The second single, “I Saw the Light,” is another song you could hear The Judds doing but an arrangement featuring mostly electric instruments and male backup singers lets us know the formula is being updated. This also went to #1. They seem to be playing it pretty safe but what they’re really doing is testing the waters. Because Wyonna’s third single had already been put out as the b-side of her first single, maybe to see if it caused any death threats or, at least, angry letters, because it was on some entirely new shit.

It goes #1 country, obviously, and it tops out at #35 adult contemporary but it also breaks into the Hot 100 at #83. That’s Wynonna’s biggest mainstream hit so far. The Judds’ music had always been pop radio-friendly country but it never really got played on pop radio. This song is more like country radio-friendly pop… If you can make yourself forget that this is Wynonna Judd, forget that you’ve thought of it as a country song for the past 25 years, the production sounds like someone took a 45 of Ray Parker Jr.’s “Ghostbusters” theme and played it at 33rpm. It sounds like Whitney Houston’s “How Will I Know” on horse tranquilizers. I like this song and I already told you, I guess it’s a country song. But if aliens land on the planet tomorrow and say they’re eliminating the human species unless I can explain to them why this is a country song, we’re history. And here’s where things get interesting. “No One Else on Earth” is released as an a-side in August of 1992. It hits #1 country on October 24th and stays there for four weeks. Country radio listeners hear this song the whole three months it takes to climb to the top of the chart. During the month that the song is #1, they hear it a lot, enough to maybe start wondering, “Wait, does this even sound like country music?”

The week “No One Else on Earth” leaves #1 it falls to #9. The week after that, #13, and, the following week, on December 5th, her label releases the next single from her album. It’s a major bummer of a heartbreak song The Judds totally would have done, called “My Strongest Weakness.” So why would they have followed up her biggest hit ever with a song that goes back to her sound from before that hit? One reason is because there wasn’t another song on her album that sounded like “No One Else on Earth,” because they were testing the waters. Start with a single that sounds like The Judds. Give them a single that sounds like The Judds gone electric. Then, blow the barn doors wide open with straight-up pop before dialing it back to The Judds’ sound and looking around to see if anyone noticed. Pay attention to how they had that “dial it back” single on the market as soon as the “pop experiment” single began to fall. See, I don’t think they were testing whether or not Wynonna could crossover to pop audiences. I think they were trying to see if her country fanbase would stick with her when she did. Because even though “My Strongest Weakness” is a comfortable return to a sound that fans of The Judds know and love, the song only goes to #4 country. Yes, that’s still a hit but it’s the first of her solo singles to not go #1. I believe this is enough for her team to decide that her country fans will not stick with her if she goes pop and here’s why: Wynonna’s second album makes a hard u-turn back into country music. Jill Colucci, the main writer of “No One Else on Earth,” doesn’t have a song on this album and nothing on this album really sounds like “No One Else on Earth.”

The album is successful. The title track and first single, “Tell Me Why,” comes out in April of 1993 and does even better on pop and adult contemporary charts than “No One Else on Earth” had done. For some strange reason, it isn’t a #1 song for fans of country music. None of the singles on her second album are. As a matter of fact, Wynonna won’t have another #1 country single until 1996 and, unless she has another one after this episode comes out, that’s her final one. It’s almost as if her loyal country fanbase bought “No One Else on Earth,” just as they’d bought everything she’d done before, realized they didn’t think it was country music and felt betrayed. It’s almost as if her team crunched the numbers and decided hitting the bottom of the Hot 100 didn’t make up for not hitting #1 country, didn’t make up for alienating her core audience because singles sell mainstream country albums. I can’t say for a fact that’s what happened but, looking at it from the outside, well, I can’t think of any other explanation that works for why the writer of her biggest hit wasn’t brought back, why the sound of her biggest hit wasn’t brought back and why her status as a country chart topper was so suddenly revoked by country music fans. I’ll point out again that these albums were successful by any benchmark except the one she’d set for herself. Wynonna’s debut album is currently certified 5x platinum. Her second album is platinum. Five million sold versus one million sold is a gigantic difference. Her third album doesn’t come out until three years after the second one and it’s the last of her albums to go platinum.

…Alone-A

What I haven’t told you is that it’s a miracle Wynonna was able to keep it together enough to continue making music at all after the year 1994. A lot happened in the three year gap between her second and third albums. Cast your memory all the way back to the beginning of this episode. Remember how Naomi Judd got pregnant by her boyfriend in high school, married him and had his baby? Yeah, that’s not what happened. When Naomi Judd and Michael Ciminella moved into their first apartment together, he learned a lot more about sex. The most important thing he learned about it was that he and Naomi hadn’t done the part that makes babies before she got pregnant. Naomi misled him into raising a child that was not his. But Michael had asked Naomi to marry him on their very first date and they’re married now, right? So maybe he should just keep his mouth shut about it, which is what he does and, according to Ashley Judd, probably the reason Naomi comes to despise and demonize Michael.

The reason I withheld this information from you until right here is that it isn’t until right here, in 1994, that Wynonna Judd, a 29-year-old woman, finds out that her father is not her father and has to react to that with the whole world watching. Ashley Judd had known this for years. She’s the reason Wynonna is at long last told the truth, in an emergency family therapy session with all three Judd women. Ashley, in effect, commanded Naomi to come clean. In the room, Naomi just cried and couldn’t talk, so Ashley finally said it: “Michael Ciminella is not your father.” Turns out, Wynonna is practically the only person who doesn’t already know. Naomi had told The Judds’ managers and publicists, even their wardrobe assistant. The reason that it’s now an emergency Wynonna be informed is Naomi’s first autobiography came out a few months before this. In this book, she lets the reader believe Michael is Wynonna’s father. She also talks a lot of trash on him, leading us to believe he’s everything from an idiot to the definition of a bad, uncaring parent. So, by this time, that manager Ken Stilts is out of the picture, following a problem with Naomi, which meant a problem with Wynonna and that all ends up in civil court. Wynonna’s new manager is her lawyer, a man named John Unger…

Now, Naomi’s book is published in December of 1993. The next month, January of 1994, Clint Black, Tanya Tucker, Travis Tritt and Wynonna all perform at the halftime show of Super Bowl XXVIII. At the time, Wynonna is the biggest star of the bunch, so she would have been saved for the end anyway but then they bring Naomi out of retirement for “Love Can Build a Bridge” with all the stars coming back to sing again, plus a pre-fame Ashley Judd and Stevie Wonder and, oh, who cares, might as well throw Elijah Wood onstage as well. (It’s posted below.) Michael Ciminella comes to the game and asks if he can ride back to Nashville with Wynonna on her bus. Her lawyer/new manager, John Unger, who knows Naomi’s secret, invites himself on the bus as well, preventing the privacy Michael wants to tell his side of the story. The emergency family meeting is called soon after this. Then, Wynonna learns she’s pregnant. Can you imagine any of this? Can we even begin to empathize, here? Maybe don’t answer yet. It’s not over.

In May of 1994, she mentions her pregnancy to some reporters. I repeat, a female country singer announces her intention to have a child out of wedlock in 1994. If that isn’t a big deal, someone forgets to tell the tabloids. Feeling as though her entire family had lied to her for her whole life (because they had), she retreats into a relationship with the father of her unborn child, a man she refuses to name in her autobiography because of how awful he turned out to be. (And all of these people are still alive and the situation seems not good, so I’ll be leaving identity out of this one.) After moving into Wynonna’s house, this guy has a hand in every aspect of her life, doing just about all the things a personal assistant would do. Nearly every piece of communication with Wynonna goes through him. Soon, she won’t make a decision without his input. All of this, it’s what she’s used to, letting someone else run things. Only this time she’s in a relationship with the person, about to have a baby with the person. When the kid is born, the father throws a fit, right there in the hospital room, demanding his last name go on the birth certificate. He grows more demanding. The romance leaks out of the relationship. They remain unmarried.

The day of that emergency Judd family meeting, Wynonna had spoken to Michael Ciminella. He told her something like he hoped they could now start developing a relationship based on truth. I’m sure he meant that. I’m sure she wanted that. But the only reason Wynonna knows the truth is because of how terribly Michael is being judged in the court of public opinion. Naomi’s out there doing interviews to promote her book and every one is like a slap in the face to Michael and what he knows is the truth. Finally, in 1995, he goes to the press – the same week The Judds are scheduled for a one-off 4th of July celebration in Naomi’s hometown of Ashland, KY. She and Wynonna make a deal beforehand that, no matter what she’s asked by the media, Naomi will not talk about Michael Ciminella. Naomi talks to the media about Michael Ciminella. Wynonna feels betrayed by her family, yet again. She returns home to her now nearly loveless relationship. A few months of that have her just about ready to kick this guy out when she finds out she’s pregnant again.

We’re probably now somewhere around September of 1995. Wynonna hasn’t put out an album since Tell Me Why, her second album in 1993. She hasn’t toured for a year. These things are bad for her career but she had planned to take a year off after the birth of her first child, so, it is what it is. Now, that year’s up and here comes baby number two. She can’t take another year off and she knows it. Even though things are super not great with this guy, they’re about to have two kids together. Maybe she thinks it will be easier to balance her career and family, if she has a husband. I don’t know. She decides to marry him, get a third album out and do as much touring as possible before the second baby is born. A few weeks before the wedding, this guy informs Wynonna’s manager, John Unger, they’ve decided a prenuptial agreement will not be necessary. Fortunately, John Unger, remember, is a lawyer. He explains there will never be a wedding without a prenup. After the wedding, Mr. Wynonna tries to get her to sign over power of attorney to him. Again, thanks to John Unger, this does not happen. Wynonna doesn’t even know what power of attorney means. After it’s explained to her, she calls her husband to ask what the fuck. He laughs it off and says all he wanted to do was sell one of the cars. Gradually, people who’d worked closely with Wynonna for years begin quitting their jobs. Tour dates fall through. Sponsorships are dropped. It seems wherever this guy gets involved, he has to throw his weight around and Wynonna’s professional and personal relationships suffer. She stops talking to her own best friend when that friend gives an honest opinion on the situation. Finally, after losing more employees than she can ignore, she sends Mr. Wynonna home from the tour and things magically get better. Near the end of 1998, she files for divorce. It’s not easy but she manages to escape this marriage.

Nobody Does

If I ended this episode the way Wynonna ends her autobiography, it would look like this has a happy ending. I don’t think I can do that. With Naomi’s health improved, in the year 2000, The Judds do a reunion tour. They still drive each other crazy but they’re older, maybe wiser, now and they deal with their issues openly. Very openly. Extremely openly. They start dealing with their issues on national television with Oprah Winfrey.

Wynonna falls in love with and marries her longtime bodyguard. Then, she finds out she’s going broke after years of overspending. The married couple enters an experimental form of therapy to work on their issues. It seems to work. As she wraps up her story, her life isn’t perfect but she’s grateful. She knows there are problems and she thinks she knows how to deal with them. There’s a wonderful sense of optimism. I truly hope that optimism is still there. Her book was published in 2005. In 2007, her husband was arrested for sexually assaulting a minor. They divorced immediately.

In 2012, Wynonna got married again, this time to Highway 101’s drummer, Cactus Moser. Two months after the wedding, he had a motorcycle accident and lost one of his legs. Fortunately, he’s still able to play. Wynonna’s most recent album came out in 2016. It’s called Wynonna & The Big Noise. I’d recommend checking out the song, “Keeps Me Alive.” You can find out more about what Wynonna’s up to now at www.wynonna.com.

Everyone who still reads the tabloids knows I’ve left out many things. I tried to include everything that seemed relevant to the story I wanted to tell. That story isn’t over yet, so I don’t know whether or not I’ve failed.

Nobody does.

Thank you for listening to (and reading) Cocaine & Rhinestones. Every episode of the podcast is written and produced by me, Tyler Mahan Coe.

Every episode, I ask readers to share what they just heard with one person. You can do that online or by bringing it up in a conversation with anyone. Those of you who’ve read every episode may be thinking, “Listen, man, I’ve told everyone I know! What more do you want from me?” I’m definitely not asking you to camp out on your friend’s front porch until they start listening to the podcast. I appreciate everyone who’s told someone already and, if the people you told started checking out the show, then they’re the ones seeing me say this and now it’s their turn to pass it on. It’s also their turn to hit “subscribe” in the sidebar (or bottom of the page on mobile). That way new episodes will show up as soon as they come out. If you’re new to podcasts and don’t have or want an app for them, you can go hit the “subscribe by email” button to have new episodes sent to your inbox as they come out. I’m pretty sure there’s an audio player right in the email you get and you can listen to without downloading anything or you can just use the email as a reminder that there’s a new episode and go read the post on the website.

Next week on the podcast, I will be telling the story of Doug Kershaw and his brother Rusty. I don’t want to oversell it but I am very excited to be in a position to tell this story. It’s one that’s very special to me for a lot of personal reasons. There is some out-of-this-world music in the episode, pretty hilarious drug stories and it crosses over into the world of mainstream rock music in a really big way, so this is going to be one you can talk about with all your friends who think they hate country music and would never check out this podcast.

-TMC

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [linked, if available]:

- Shania Twain – “Whose Bed Have Your Boots Been Under?” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Charley Pride – “The Snakes Crawl at Night” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Judds – “Turn It Loose” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Joni Mitchell – “River” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Doc Watson – “Country Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dolly Parton – “The Seeker” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Huey Lewis & The News – “I Want a New Drug” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Asleep at the Wheel – “Route 66” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Loretta Lynn – “I Wanna Be Free” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Judds – “Coat of Many Colors” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dottie West – “Lesson in Leavin'” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Chuck Mangione – “Hill Where the Lord Hides” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Judds – “Mama He’s Crazy” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Teresa Brewer – “Had a Dream” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Elvis Presley – “Had a Dream” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Judds – “Had a Dream (For the Heart)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Judds – “Why Not Me?” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Judds – “Girls’ Night Out” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Judds – “Love Is Alive” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Judds – “Have Mercy” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Judds – “Granpa (Tell Me ‘Bout the Good Old Days)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Judds – “Rockin’ with the Rhythm of the Rain” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Judds – “Love Can Build a Bridge” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynonna Judd – “She Is His Only Need” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynonna Judd – “I Saw the Light” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynonna Judd – “No One Else on Earth” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynonna Judd – “My Strongest Weakness” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynonna Judd – “Tell Me Why” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynonna Judd – “Only Love” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynonna Judd – “Rock Bottom” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynonna Judd – “Girls with Guitars” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynonna Judd – “Keeps Me Alive” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Excerpted Video

These may be removed from the Internet in the future (for any of a number of reasons) but, for now, here they are:

The Judds – Ralph Emery Vault from The Judds on Vimeo.

Commentary and Remaining Sources

Every single time I pressed play on one of the songs in this episode was an intensely nostalgic experience, like when you walk into someone’s house for the first time and it smells exactly the way your grandmother’s house used to smell 30 years ago. Something akin to that familiarity. It literally gave me goosebumps. No adult in my life was a particularly big fan of The Judds or owned their albums or anything like that. It’s just that they were on the radio constantly. This is very much the music of my childhood.

This episode is going to end up being one of the longest in the first season, which is pretty funny because, originally, this was just going to be a song episode, like “The Pill” or “Okie from Muskogee.” That one segment where I detail the way “No One Else on Earth” was released and speculate on the strategy and consequences of it? That was the original focus of this episode. I wanted to really dig in to an end-of-the-century example of pop music on country radio and give whatever context may be necessary to understand it. It became clear pretty immediately that I didn’t have the full context myself. I never have been a person to read tabloid journalism and I stopped paying attention to almost everything in the 2000s, so I was not aware that this family has been a very public shitshow for the past two decades. I had a general awareness of how many decisions were not being made by Wynonna for herself in the ‘90s and I expected to talk about that but when I got to the year 1994, I realized this isn’t a story you can look at one little piece at a time.

I’m not sure if this was ever a part of the tabloid narrative – it probably was – but a common conspiracy theory I’ve often heard in person is that Naomi Judd never really had a liver disease. Some people think The Judds just couldn’t stand each other anymore. They think it was a publicity stunt ahead of the farewell tour, a good storyline to launch Wynonna’s solo career. Look, I’m not going to pretend I know the truth one way or the other on this. We’ve seen examples of Naomi being a dishonest person, so everything she says from now on will come under scrutiny. Personally, I don’t see this being a lie. She wanted to be famous her entire adult life. Why would she give up the spotlight? Also, we’ve seen how terrible these people are at keeping secrets. Yeah, she managed to hide the truth about Wynonna’s father all the way through getting a book published but, once the book came out with the lie in it, it was a little over a year before the truth was in headlines. Every time a Judd writes a book or goes on TV to tell their side of a story, another Judd writes a book or goes on TV to tell their side of a story. I mean, if we’re going to get silly about it we may as well say The Judds have always been a perfect family and every disagreement they ever had was to get people hooked on a real-life soap opera. Because they’ve certainly gotten more long-term publicity out of being a dysfunctional family than they ever got from the Hepatitis C announcement.

I said “white people blues” and “white people rock” in this episode so I’m sure someone’s pissed about that. It was a description for the two songs mentioned right before that and, if I may say so, a very accurate description. It was not my intention to insinuate that either of The Judds do not listen to black blues artists or black rock artists because I have no idea whether or not that is the case.

I should also clarify that slowing down Ray Parker Jr. or Whitney Houston would not literally sound like “No One Else On Earth” in any melodic or textural sense. It’s just a way of thinking about the production on the song.

Some people familiar with the full Hank Williams Sr. interview response I used in the beginning may think I was twisting those words to make the opposite of Hank’s point, so let’s get into that. First, though, you have to understand the reason why he was saying any of this is because a reporter asked him to explain the global appeal of a genre of music made by a bunch of American hillbillies, so he’s responding to a direct question about why people can relate to, and this is the important part to specify, a hillbilly singer:

“You ask what makes our kind of music successful. I’ll tell you. It can be explained in just one word: sincerity. When a hillbilly sings a crazy song, he feels crazy. When he sings, “I Laid My Mother Away,” he sees her a-laying right there in the coffin. He sings more sincere than most entertainers because the hillbilly was raised rougher than most entertainers. You got to know a lot about hard work. You got to have smelt a lot of mule manure before you can sing like a hillbilly. The people who has been raised something like the way the hillbilly has knows what he is singing about and appreciates it. For what he is singing is the hopes and prayer and dreams and experiences of what some call “the common people.” I call them “the best people,” because they are the ones that the world is made up most of. They’re really the ones who make things tick, wherever they are in this country or in any country. They’re the ones who understand what we’re singing about, and that’s why our kind of music is sweeping the world. There ain’t nothing strange about our popularity these days. It’s just that there are more people who are like us than there are the educated, cultured kind. There ain’t nothing at all queer about them Europeans liking our kind of singing. It’s liable to teach them more about what everyday Americans are really like than anything else.”