[This episode of Cocaine & Rhinestones is the second episode in a three-part series on the song “Harper Valley PTA.” If this is the first episode of the podcast you’re listening to, I would recommend going back and, at least, listening to last week’s episode before this one, even if you’re just a huge Jeannie C. Riley fan and you don’t even know who Shelby Singleton is. If you haven’t heard (or read) last week’s episode, you’ll be missing out on a lot of context and I’m not going to be doing very much recapping.]

Jeannie C. Riley’s debut single sold over a million copies within ten days of being released but she never wanted to record the song. She’s often considered a one-hit wonder. We can easily disprove that.

In the late ’60s, Jeannie C. Riley became country music’s most blatant sex symbol to date but she never wanted to wear those clothes. Small town girl with big dreams goes to the city and lets it break her in order to make her. Total cliche, right?

Sure.

Except Jeannie’s choice to bury the story in lie after lie turns it into a mystery tale of obscured identity, infidelity and blackmail. In this episode, some truth sees the light of day, maybe for the first time ever.

Recommended for fans of Johnny Paycheck, Johnny Russell, The Wilburn Brothers, Tom T. Hall, Little Darlin’ Records and mystery novels.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

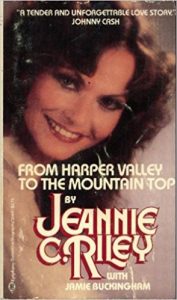

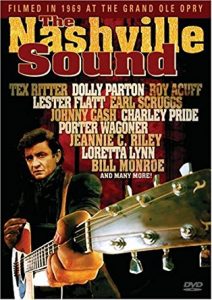

In addition to The Library, this book and DVD were used as sources for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

What’s Hit?

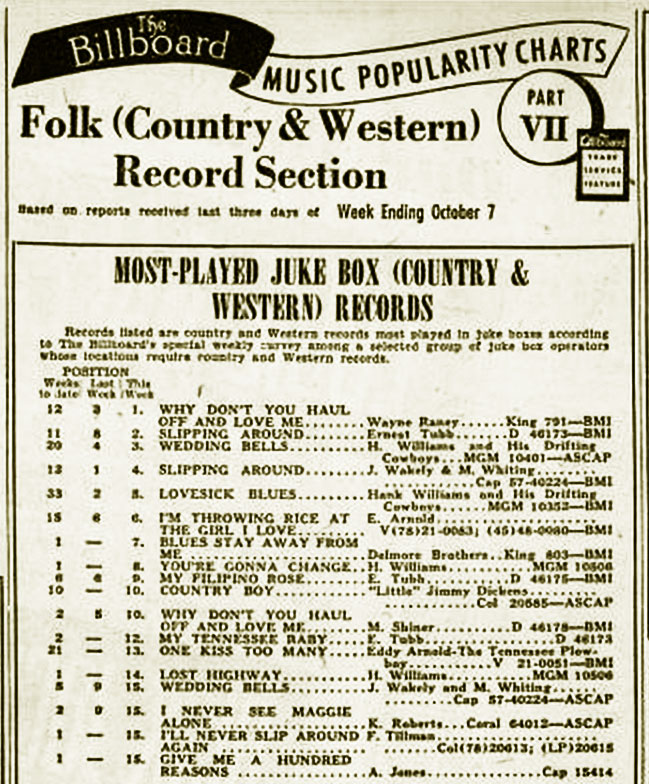

Last week, we spent some time looking at how far outside of the box Shelby Singleton was willing to go for a hit song. Now, are we sure we know what a hit song is? How to define it? It’s safe to say any song that hits the Top 10 could be called a hit, right?

Okay.

This past May, when I began working on this podcast, I spent about a week listening to every song to ever go #1 on the Billboard country chart, in chronological order, from the first year the chart existed, in 1944, until this show’s cut-off point in the year 2000. I needed to make sure I’d heard them all to build a timeline of what happened in the mainstream of country music in the 1900s. There were quite a few songs I’d never heard before. Unless you’ve purposefully sat down to give yourself the same experience or spent the past 70-something years of your life glued to country radio, the same thing is true for you. #1 songs, hit songs – completely absent from our personal experience of country music, even when the song at #1 the week before or the week after is one of our favorite songs of all time.

Now imagine how many Top Ten hits between 1944 and the year 2000 we haven’t heard. Probably hundreds of hit country songs you’ve never heard in your life, I’ve never heard in my life. So we can say “all hits are not created equal.” Not in the mind of the audience and definitely not in the mind of the record industry.

[I should give a disclaimer here that commercial success is obviously not everything, obviously not a gauge of artistic merit. There are brilliant country artists who’ve never had a hit in their lives. That’s not what we’re talking about today.]

If we’re saying Top Ten singles are hits (and I believe we should say that), then just having hits wasn’t enough for this industry. You had to have more hits, bigger hits. It was called the record industry. Move units, make money or get out of the way for the next artist who will. Always be scaling up. Anything that isn’t as good as or better than the last thing you did, you might as well have not done it and you’ll probably end up wishing you hadn’t.

I think the worst thing that could happen to a country recording artist in this climate is for their very first single to become a #1 hit. You can’t do any better than that. The only way to improve on that is to stay #1 for more weeks, sell more copies. Even if you manage to do that, it’s only a matter of time until you put out a song that only goes to #2… or #5…

“But that’s still a hit!”

Oh, sure. Sure it is.

Or maybe it’s the beginning of the end. Maybe you just don’t have the stuff anymore, kiddo. We gotta get those numbers back up to where they were or, well, it ain’t gonna be good.

Imagine you’re a new country artist and your very first single goes #1 country and pop. How screwed do you think you are? There aren’t many people you can ask about this. Billy Swan is one. Jeannie C. Riley, the singer of “Harper Valley PTA,” is the other one. Those are the only two people alive who’ve had their first single go #1 country and pop. Neither one of them ever had another #1 song. I’ve heard them both called one-hit wonders.

Billy Swan never even got back in the Top Ten. Although, he did also write his one hit, “I Can Help” and Elvis Presley recorded that, so I assume Billy’s doing fine.

Jeannie C. Riley put out five more Top Ten hits, four of which crossed over into the Billboard Hot 100. These are country songs, by the way – none of that stripped-down Nashville Sound stuff the industry bent over backwards to push at pop audiences. Jeannie was achieving crossover success with one of the most unsophisticated Texas twangs you’ve ever heard and a hardcore country sound behind it. That’s not what one-hit wonders do. But because her first single sold maybe six million records, nothing she did after that mattered.

Country Girl

Jeanne Carolyn Stephenson was born in a small Texas town in 1945. In 1962, while still a senior in high school, she married her boyfriend, Mickey Riley, and became Jeanne Carolyn Riley. So, “c” stands for Carolyn.

Her uncle was a country guitar player and songwriter. Nobody you’d know but, in the tiny town of Anson, TX, just the fact that he’d gone to Nashville to record in a real studio was a big deal or at least Jeannie seems to think people thought so. Her husband Mickey knew it was Jeannie’s dream to move to Nashville and become a famous singer. He was supportive of that but they decided to wait until Jeannie finished high school and save some money for the move. Then, Jeannie found out she was pregnant and they had a baby… in 1966. Yes, that is four years after they got married and, unless it took Jeannie four years to pass 12th grade, the math doesn’t add up at all for her to use the baby as an excuse for why they stayed in Texas. I’ll get to it in a second.

One day, Jeannie says, she gets a letter from the great pedal steel player, Weldon Myrick, who’d seen her sing at a local jamboree and just had to write her to say that he thought of Jeannie’s singing every time he heard Connie Smith sing “Once a Day.” Now, in just a minute, you may decide Jeannie’s making this part up but it is possible that it’s true. Though you wouldn’t know it from only having heard “Harper Valley PTA,” she was able to sing in a somewhat similar style to Connie Smith. So, Weldon’s letter gives her a little encouragement.

The next time Uncle Johnny goes to Nashville, he invites the entire family on the trip and they go. Still in 1966, here, thirteen people pile into two cars to make the trip. Up in Nashville, they drive around lower Broadway to look at Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge, Ernest Tubb’s Record Shop and The Ryman Auditorium – all that country music tourist stuff. Uncle Johnny gets them backstage at the Grand Ole Opry and Jeannie’s all starstruck. She gets an autograph from Connie Smith. Jackie Phelps, the guy you’d later see playing guitar on Hee Haw, takes Uncle Johnny aside to give him some advice, “Your little niece is a pretty country girl and I’d like to save her and her husband some heartache. If she’s got talent, tell her she doesn’t have to sell her body to make it to the top. She can make it if she knows the right people. But if she gets in with the wrong crowd, they’ll destroy her – and her home, too.”

There Never Was a Time

Okay, freeze.

Jeannie C. Riley’s autobiography is really the only source I can use for this stuff and it’s super sketchy, to say the least. This is the first of several outlandish scenarios where famous people give her incredibly personal advice that is also so extremely specific, it’s almost as if they can see into Jeannie’s actual future mere moments after meeting her for the very first time.

You’re a professional musician. A colleague of yours brings his niece to see a show. You take it upon yourself to call the guy aside and tell him to make sure to let his niece know not to be a hooker? Not likely.

Jeannie does go on to find herself in some bad situations and I don’t doubt for a second that they really happened. But believing her about that does not mean I have to believe everything else she says.

There’s all these run ins with celebrities who seem to have psychic powers. The timeline she presents often makes no sense, fine, but at least one major part of her story is deliberately misrepresented. She is blatantly lying about certain things. There’s even a note at the beginning of the book about how several names and some details have been changed to protect people…

Basically, it could not be more clear that this autobiography is more like what you’d call an autohagiography, the Hollywood movie version of these events. They might as well have printed BASED ON A TRUE STORY on the title page. I should say, this is one of those celebrity autobiographies that’s written with the “help” of an author. So, you know, it’s possible this guy had a hand in these embellishments. You can make up your own mind – that’s what I’ll say – but this is gonna get real crazy so, please, try to remember this.

Here’s an example of a small type of thing that I probably wouldn’t even mention if I only noticed it once or twice. The book opens with her locking up the office building in Nashville where she worked as a secretary, walking over to a recording studio and being greeted by Shelby Singleton handing her the lyrics of “Harper Valley PTA.” We’ve got Shelby saying,“It’s just right for your voice. Tom Hall has caught the angry mood of the country. Let’s see if you can make it sing.” The problem is, as you’ll hear in a few minutes, the entire week before this, Jeannie had been arguing with everyone about not liking this song and whether or not it would be released under her own name or a pseudonym. In the very next paragraph, she says she’d already studied the lyrics, which she would have gotten from Shelby. Why does she have Shelby presenting the lyrics to her here with such pomp, as if for the very first time, as if she’s never heard this song before? Like I said, small thing. I would let it slide. But this is a death by a thousand cuts situation.

There’s at least one scene where two people go back and forth with lines of quoted dialogue, in a conversation that Jeannie was not there for and could not possibly remember with such detail, even if she was blessed with total recall over a decade after the fact.

There’s one more scene where she’s driving her car while upset, “half blind from the tears.” She accidentally speeds over some railroad tracks, just ahead of a crossing train and, I’m quoting here: “The train loomed over me as I roared across the tracks, missing my back bumper by less than a foot. The vacuum created by the rushing locomotive and the rumbling wheels almost flipped over my car. The screeching-” blah blah blah…

“Half blind from the tears” yet she knows within a 12-inch margin of error how close a train passed to the back bumper of her car.

So that’s what I’m working with, here. And… Whatever. You’ll see.

Hanging on the Telephone

Okay, we’re still in Nashville, the night Jeannie’s uncle takes her backstage at the Opry.

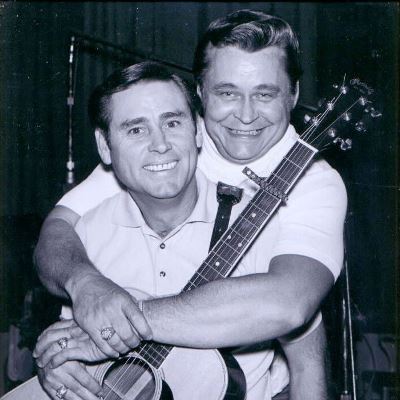

When they leave the Opry that night, Doyle Wilburn of the Wilburn Brothers has agreed to listen to Jeannie sing, if they’ll come by the office of Sure-Fire, his publishing company. A few days later, they drop in to the Sure-Fire office and meet Johnny Russell, who is a staff songwriter there. Johnny Russell listens to her sing. They decide to have her go in the studio that night and the next to record a four-song demo tape. They have a photographer take some pictures of her. Jeannie thinks all of this means she’s on her way to becoming a star.

Johnny Russell

The second night of recording, within 48 hours of meeting her, Johnny Russell pulls Jeannie and her husband, Mickey, aside, to tell them, “I’ve watched you kids ever since you got here and I need to say something to you. Nashville is good to you when you’re on top. But it’s a mean city, too. This business of wanting to be number one gets in your blood. It consumes you until you can’t think of anything else. It’s like drugs, only worse, ‘cuz there’s nothing you can do to get rid of it. You’ll leave your family. You’ll leave your self-respect. You’ll do anything to reach the top – and anything to stay there. I’ve seen it happen too many times. Most people think they are the exception. They come in here with high morals and high ideals – and lose them overnight. The pressures are too much. What I’m saying is this: I don’t think Jeannie can make it here. She’s got a good voice and you’re a fine young couple. But this city will chew you up, swallow the juice and spit you out like a dry hull on the street. Go back to Texas. And stay there.”

Wow, that is one hell of a monologue, huh? I don’t know how anyone gets anything done in the music business when they’re delivering fully polished 150-word speeches like that to everyone they’ve known for 48 hours.

Anyway, after a week or so, the Texas crew heads back to Texas. Doyle Wilburn had told them the Wilburns would be needing a female vocalist for their upcoming September tour of Germany. Jeannie should expect their call. All through July, she expects the call. All through August, she expects the call. Of course, it never comes, so she gets all bummed out, until Mickey comes home from work one day and tells her to start packing. He’s sick of seeing her mope around the house. They’re moving to Nashville.

As they cross the city limits sign into Nashville, she and Mickey make a pact that they’ll always travel together as a family, the baby too: “Show business might chew up other folks and spit them onto the sidewalk but not us. We’d show ‘em. We were going to make it. Together.”

This is the end of 1966. Because of everyone Jeannie starts having sex with and the fact that she changes their names and the names of the companies they work for, it gets really confusing to work out the specifics of what happens when and where for the next year. For instance, she refers to her first manager, Paul Perry, as “Pete Terry” through her entire book because of the affair she later has with him. This other guy gets named “Phil Blackman” and he’s a big shot at “Black Rose Records” based out of New York. Phil Blackman is our Big Bad Wolf.

Uncle Johnny bought a gas station right before Jeannie and Mickey moved to Nashville, so that’s where Mickey starts working. They live in a motel room, then a small apartment. Jeannie keeps calling Sure-Fire music to find out why they didn’t hire her for that Wilburn Brothers tour. She eventually finds out that tour was canceled and then gets to work furthering her career by checking the mailbox and waiting for the phone to ring. She writes that she spends weeks, waiting for the world to notice her, resenting her husband for working 12-hour days at a gas station to support her and the baby, while also begging him to move them to a bigger apartment closer to his work.

One day, she finally realizes she’s going to have to actually try to get people to care that she exists. She gets all dolled up and drives, with her baby, down to Music Row to look for this powerful woman she’d heard of who was from a town in Texas 25 miles away from where Jeannie was from. She apparently thinks she can meet this lady, say “hey, I’m from Texas, too” and get a record deal or something. She has no idea where this lady’s office is supposed to be. She just starts walking into publishing companies to find out if that lady works there or not. When some kid asks if she’s trying to get a demo tape heard, Jeannie pulls out her tape and the kid takes a listen. He seems to like it, plays it for his boss, who says it sounds too much like Loretta Lynn and they tell Jeannie to kick rocks. She goes back to her car with the baby and cries, then decides to drive over to the gas station where Mickey works.

When she gets there, Mickey’s talking to a guy named Jerry Chesnut, a rich guy who owns a vacuum cleaner business but also wants to be a songwriter. (You’ve heard the song he’d write a few years after this called “A Good Year for the Roses.”) Mickey has a copy of Jeannie’s demo tape that he plays in the gas station, just in case someone important happens to come in and hear it – and care. Chesnut isn’t really important yet but he did strike up a conversation and offer to play the demo tape for his friends at Monument Records. A few days later, he calls to say Monument is interested but they want to change Jeannie’s name because they’re already doing well with Jeannie Seely and let’s not get carried away with the Jeannies over here, right? Our Jeannie’s not thrilled about this but Jerry thinks they can get Monument to back off the name change, if they stay on it.

Jerry Chesnut & George Jones

Jeannie gets shown off at a DJ convention, introduced to everyone in town as “Tina Stephens,” the next girl they’re gonna sign and do big things with… but then she gets forgotten about because, apparently, a major female artist on the label doesn’t like Jeannie. Or, Tina. Or, whoever. Back to square one.

Jerry Chesnut meets a radio DJ, named Paul Perry, who knows Phil Blackman, a made up name for a real important guy at Black Rose, which is also a made up name for a real record label. Remember this sentence: that DJ Paul Perry sends Jeannie’s demo and a promo picture to Phil Blackman in New York City.

Blackman expresses interest in recording Jeannie when he comes to Nashville, sometime in January. It ends up being early February of 1967 when Jeannie walks in to Black Rose’s office for the first time. She writes literally nothing about the conversation, only that she finds Phil Blackman very attractive and she leaves with a contract. That night, she begins fantasizing that Blackman will fall in love with her. Within a week, in reality, they’ve kissed. Blackman goes back to New York City for business. When he returns, a few weeks later, he and Jeannie start having a full-fledged affair.

Swallowing the Juice

Now, I don’t like dwelling on this soap opera stuff unless the story cannot be told without it, so here’s the relevant information.

That DJ, named Paul Perry, becomes Jeannie’s first manager. She technically gets a single released on Black Rose Records but it’s only technically released – no money is put into promoting it and not even Jeannie thinks it’s any good. But she does think she and this rich, powerful man are in love with each other, so she’s not too worried about that record.

Then, one day in Blackman’s apartment, Jeannie’s laying naked on the couch, after having sex with him, when she’s suddenly blinded by flashes of bright light. There’s Blackman, holding a camera with a strobe flash attachment. Jeannie freaks out. He tells her there’s no film in the camera. She asks if he really loves her. He laughs at her, says mean things to her about how stupid she is and she leaves, crying.

Fast forward to six months later. It’s early in the fall of 1967. Jeannie’s in Las Vegas for a week, as Johnny Paycheck’s opener. Paycheck is on his way up after having his first Top Ten hit the year before with “The Lovin Machine.” Phil Blackman is also in Las Vegas but Jeannie manages to resist his advances.

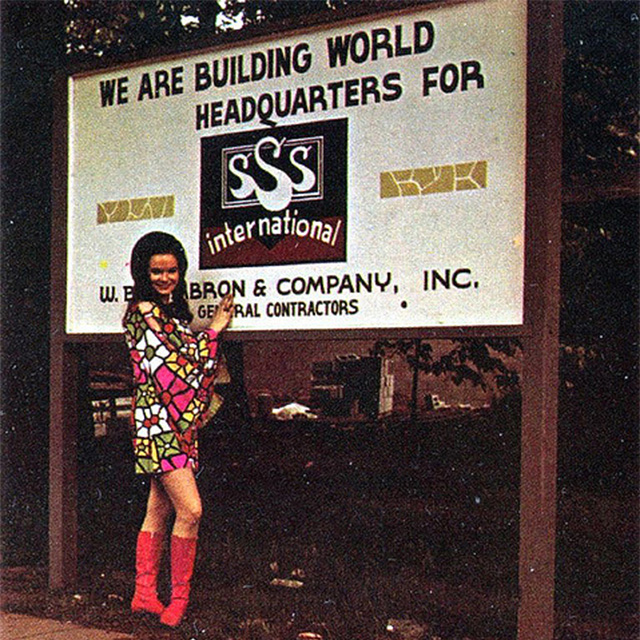

Fast forward, again, to January of 1968. Jeannie gets Blackman to release her from her contract so she can go record for Little Darlin’ Records. This is the record label started by Johnny Paycheck and his producer, Aubrey Mayhew, who had heard Jeannie sing in Vegas and decided he’d like to record her. Aubrey does record her, a single is released on Little Darlin’ but, like the Black Rose single with Phil Blackman, it’s only technically released – not really promoted because they “wound up in contract difficulties.” I will come back to this.

Meanwhile, Jerry Chesnut has decided to get out of the vacuum cleaner business and all the way into the music business, opening up a Music Row office for his publishing company. He hires Jeannie as a secretary, which is where she’s working when a songwriter friend asks her to sing on the demo of his new song he wants Shelby Singleton at Plantation Records to hear. Clark Bentley’s “Old Town Drunk” comes out on Plantation Records in 1968 but, when Shelby hears the demo, he’s more interested in the voice of the singer than the song. If you remember last week’s episode, this is the part where he wants to meet that singer to see if she’s got the “image” he’s looking for to sing “Harper Valley PTA.”

Here, on Jeannie’s side, she wants to listen to “Harper Valley PTA” before she agrees to anything. Her manager, Paul Perry, thinks she’s crazy for not getting on board, sight unseen, but he brings her a tape. She doesn’t like the song. Just doesn’t like something about it. She says it sounds like a soft re-do of “Ode to Billie Joe.” Now, Paul Perry and all her friends think she’s crazy. She agrees to meet with Shelby and there’s something she doesn’t like about him, too.

Shelby tells her they can make a pop hit together but they’ll have to change her name because there’s too many Jeannies in Nashville. Same old story. He wants to call her “Rhonda Renae.” She’s thinking about that when Perry says if Jeannie doesn’t take this deal then he can’t represent her any more. It’s not gonna get any better than this. She signs the papers, goes home and cries about it. Her husband, Mickey, comes home to find her upset, hears the story about them wanting to change her name, calls Paul Perry and yells at him to tear up the contract because Jeannie’s not doing it.

The next day, all the business people convince her they’ll let her keep her own name if she just comes in on Friday after work to record this damn song. The entire day Friday, Jeannie’s pissed off at the world. She feels like she’s being backed into a corner and talked in to doing something she doesn’t want to do. On top of that, she’s sure everyone’s lying to her about getting to use her real name. Still, she goes to the studio, channels her anger into the song and nails it on the second take. Shelby tells Jeannie they’ll use her middle initial to make her stand out more from the other Jeannies and add an “i” to her first name so people know it’s not pronounced “Jean.” Finding out she really doesn’t have to be Rhonda Renae, plus the fact that everyone in the room seems certain she just cut a massive hit song, improves Jeannie’s mood. She calls her mother at 1 in the morning to tell her she just recorded a song that’s gonna be the #1 song in the country.

The masters are mixed and sent to the pressing plant on Saturday morning. Jeannie spends Monday handwriting hundreds of personalized notes to go with promo copies to DJs all over America. Anytime she comes to her own name or the name of the song, she switches from black ink to red so it stands out on the page. A station in Ohio plays the single twenty-six times in one day. Other stations ban it because they don’t like her uppity tone. Love it or hate it, everyone talks about it.

According to Jeannie, she and Mickey take a copy over to Ralph Emery at WSM. This doesn’t necessarily conflict with Jerry Kennedy’s story about Shelby taking over an acetate the night of the session. Jeannie would want Ralph to have a real copy of the record. But, then, Jeannie says Ralph tells Mickey, “Y’all be really careful. So many families break up as soon as the singer hits the big time.”

The next Friday, they’re in Philadelphia for Jeanie to sing her song on TV. Saturday, New York City. Jeannie’s with Mickey, Paul Perry and his wife, Shelby and a dozen other business people from Nashville – a real entourage. They stay in nice hotels, drink champagne, order room service and leave huge tips at dinners. Jeannie doesn’t realize how all this works until later, when she finds out she’s the one paying for all of that. Jeannie and Mickey don’t need the help spending money. They’re throwing down major cash on clothing, jewelry, hairstyles, cars. All the usual rockstar stuff.

A week after New York, they’re in Florida, doing a show with Waylon Jennings. Out of nowhere, Waylon tells Jeannie that she won’t stay married to Mickey for long because “he just don’t fit the scene.” (If you ever need to find out exactly what’s wrong with your life, all you have to do is go stand by a country musician for a few minutes. They’re all psychic and chomping at the bit to give you advice.)

Anyway. Pretty soon, Jeannie starts spending too much time with her manager, Paul Perry. One night, they’re sitting around holding hands and Perry’s talking about how careful Jeannie has to be now that she’s on top. He sure hopes she doesn’t have anything in her past that could come back to haunt her. You know, like, nudie pictures taken by Phil Blackman?

It Really Did, It Happened Just This Way

Back in Nashville, first thing Monday morning, Jeannie heads over to Black Rose Records. There’s Blackman, in his office, packing up a stack of brand new Jeannie C. Riley records, made from her old sessions with him. Now that Jeannie’s got the biggest hit in the nation, these records will sell.

They argue. She demands the naked pictures. He plays stupid, at first, but then says it’ll take him a couple days to get them, come back Wednesday. Skip to Wednesday, Blackman’s got a manilla envelope, like you see in every movie about a private detective, and he wants to give it to Jeannie but, first, she’s gotta sign a new piece of paper saying she won’t sue him for releasing her old recordings. See, he’s legally allowed to do that and she’ll even get paid royalties and everything. It’s just that he lost their original contract, so sign here… and here… and you can have those pictures.

Of course, she signs the thing.

Then, without even looking in the manila envelope, she asks him to burn it, which he does, in front of her. By the time she gets home, half an hour later, the news is reporting that Black Rose Records has filed a lawsuit against “Harper Valley PTA”‘s singer and record label for breach of contract.

Okay. Here’s the thing: Phil Blackman and Aubrey Mayhew are, at least partially, the same person.

You do remember Aubrey, right? Johnny Paycheck’s producer that heard Jeannie sing in Vegas, wanted to record her and that’s why she got Blackman to let her out of her contract in the first place?

Yeah. That’s all bullshit.

Phil Blackman and Black Rose Records are not fake names for someone and something that happened before Jeannie got involved with Aubrey Mayhew and Little Darlin’. Jeannie tells the same story two different ways as a red herring. Black Rose Records is Little Darlin’ Records, which is also the explanation for why Jeannie would be in Las Vegas opening up for Johnny Paycheck when all she’s supposedly done is one barely released single for Black Rose Records.

If you were to back up this post and reread the part about how Phil Blackman came into Jeannie C. Riley’s life, you’d be listening to the story of how Aubrey Mayhew came into her life. You’d be listening to the story of how Jeannie C. Riley came to be signed to Little Darlin’ Records. I know this because it’s described exactly the same way in court documents related to the lawsuit Jeannie just told us about – “As to Little Darlin’ Records, the Amended and Supplemental Bill asserts: That prior to the time complainant was incorporated, its president Aubrey Mayhew did business in New York New York as an individual under the proprietary name of Little Darlin’ Records – that his first knowledge of defendant, Riley, was a letter addressed to him on the date of December 8, 1966 by Paul Perry, enclosing the tape and photo mentioned.”

There was no barely released Black Rose single before the barely released Little Darlin’ single. There was one barely released single. The “contract difficulties” Jeannie mentions to explain why her Little Darlin’ single suffered the same fate as her Black Rose single? That’s this lawsuit. The court document sheds more light on this.

In response to Mayhew’s lawsuit, Jeannie tells the court that Mayhew was never convinced she had enough talent to succeed as a recording artist and did not undertake to produce any records of her voice for general distribution. In other words, Aubrey Mayhew didn’t think Jeannie was that good of a singer. He was using her as little more than a session vocalist for demo tapes he needed done anyway, while letting her believe she was a real recording artist. Jeannie seems to think that one single was just him going through the motions to string her along and she’s probably right.

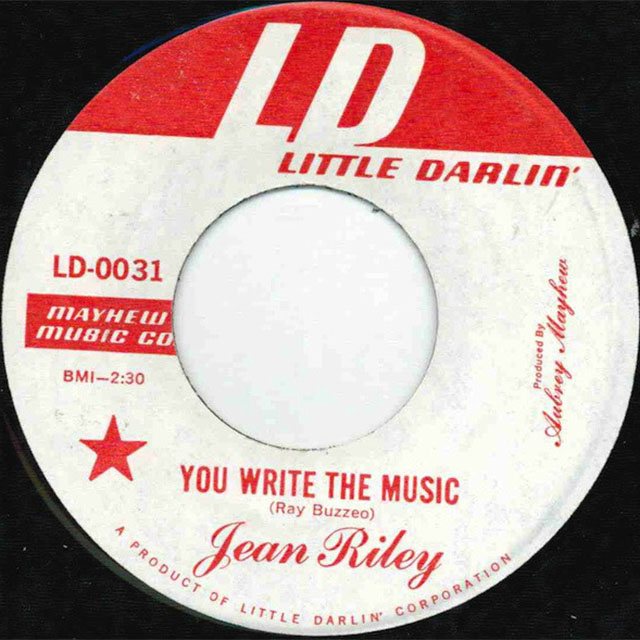

Speaking very strictly, “Harper Valley PTA” is not her debut single, as I said it was in the intro of this episode, but her first single may never have been meant for an audience larger than her immediate circle of family and friends, something physical for Jeannie to play pretend with to keep the whole charade going. It was called “You Write the Music,” credited to Jean Riley, “released” on Little Darlin’ records in 1967.

Aubrey’s first mistake was signing Jeannie to a real recording contract, which stipulated that she be recorded four times a year, a stipulation not met by using her for demo sessions. His second mistake was releasing her from her contract on April 3rd of 1968, four months before she recorded “Harper Valley PTA.”

Now, here are the two big questions I don’t think I can or should even try to answer: Did Aubrey Mayhew and Jeannie C. Riley have an affair? And, did Aubrey Mayhew take naked photographs of Jeannie C. Riley without her consent and then blackmail her?

Technically, Jeannie has never alleged either of these things against Aubrey Mayhew. That was Phil Blackman. I’m going to play it safe and point out that it’s possible Phil Blackman is meant as an amalgamation of more than one person. I’m not, in any way, a professional investigator. All I did was read a bunch of publicly available information and match it to what Jeannie wrote in her book. As far as I can tell, I’m the first reader of Jeannie’s autobiography who cared enough to take the time to look into this. Or, at least, I’m the first one to talk about it. Searching Jeannie’s and Aubrey’s names together only brings up information about them having worked together and information about this lawsuit. But, listen: even if Phil Blackman is 100% Aubrey Mayhew and even if we choose to 100% believe everything Jeannie says about him, that still doesn’t mean Aubrey Mayhew took those pictures. Jeannie says she had him burn the envelope without looking inside. She even brings up the possibility herself that the envelope could have been empty. It doesn’t look like any pornographic photographs were mentioned in the courtroom, at all.

The case was ruled in favor of Shelby Singleton and Jeannie C. Riley.

The Girl Most Likely

Back in the business of promoting their hit single, Jeannie gets sent to charm school to learn how to walk, talk and act onstage. Then, she’s sent on tour – concerts, talk shows, radio shows, live TV appearances. Her hometown names a day in April “Jeannie C. Riley Day” and there’s a big ceremony for that. She gets to do “Pickin’ Wild Mountain Berries” with Glen Campbell on TV. She gets to live her dream of performing on the Grand Ole Opry.

But then she gets her first royalty check and finds out how much of the money being spent is hers – basically, all of it. She’s always expected to hang out and be nice to industry people. One night, there’s a scene with Mickey when a random suit at a party is too persistent in trying to get Jeannie to dance with him. Mickey grabs the guy’s wrist and tells him to back off. Later, Shelby tells Jeannie that Mickey needs to stay home if he can’t control himself and Mickey is banished from the road. If you’re starting to get the idea that Jeannie’s always thought of as little more than puppet for the people behind the scenes of her career, I would say that seems accurate.

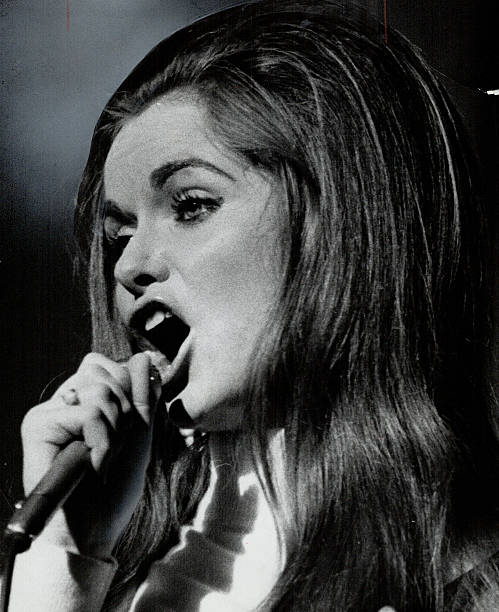

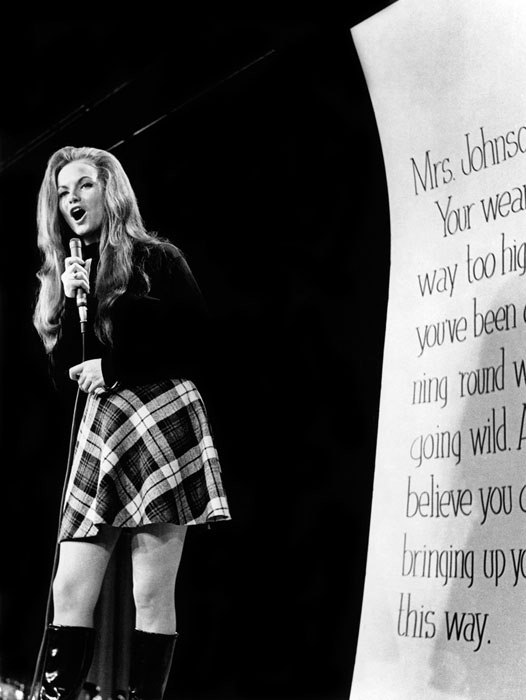

Now, aside from the song itself, the biggest impact Jeannie C. Riley had on country music with “Harper Valley PTA” was in fashion. It seems ridiculous today but, in the late ’60s, that line in the song about the single mother wearing miniskirts? That, in itself, was enough to make a lot of country music fans gasp and turn off the radio. And, while the song is actually sung by the daughter character, who doesn’t dress that way, every time you see Jeannie, she looks like Mrs. Johnson. Her style (or, more accurately, the style she was made to wear) would best be described as “mod,” like Nancy Sinatra in her “These Boots Are Made for Walkin'” phase, way before any other women in country music were dressing that way. We’re talking miniskirts, go-go boots and, in October of 1968 – the first year the CMA awards were televised – a ridiculous dress. The ruffles start halfway up her rib cage and poof way out like they would to make a bell shape down to the ground but then it all just stops, halfway down her thighs, showing off legs and high heel cowgirl boots. She looks like an ostrich.

After seeing the dress but before the show, she called Shelby Singleton to yell at him. In the middle of her tirade – after she tells him she’s not miss Harper Valley PTA, she’s an artist – Shelby interrupts her to say, “You’re not an artist, baby. You’re a commodity – a miniskirted, silver-booted commodity. Now be there early. We’ve got a show to rehearse.”

That’s one exchange that I don’t doubt for a second happened just like that.

The rest of Jeannie’s book is about her struggles with infidelity and conversion to religion. More people seem to have mystical psychic powers. Like, after a divorce from Mickey, a random sales clerk in a department store somewhere stops Jeannie to say, “Your ex husband still loves you. God wants you to go back to him.” Bullshit like that. She tells the story of the first time she tries pot – having an intensely spiritual vision that sends her into a fugue state for close to 24 hours and sounds more like an ayahuasca trip than any weed I’ve ever smoked. From the nightmare she describes, you’d expect that to be the only time she ever toked up but there’s a video clip of Ralph Emery interviewing her (posted below) that seems to suggest otherwise.

Oh, Singer

So, I want to get away from her autobiography for the rest of this episode and talk more about the music Jeannie made after her hit. Because that last sentence is pretty typical of the way people talk about Jeannie C. Riley’s career – a reference to her “hit,” as if she had only one. A one-hit wonder, if you will.

While it’s true she never took another a song to #1 on both pop and country charts, not many people have ever done that. The only other woman to do that in the 1900s is Dolly Parton with “9 to 5” in 1981, making Jeannie the first woman to ever do it. If you don’t count the farce with Little Darlin Records, which you should not, she’s the only woman to do it with her debut single. It’s so unfair to judge the rest of her output against that. That’s like mocking a rookie basketball player for only breaking a world record one time.

Jeannie’s follow-up single to “Harper Valley PTA” was called “The Girl Most Likely.” Sticking with the formula, it’s another song about prejudice in a small town. This time, it’s the girl who everyone thought would be the first one to get in that special kind of trouble only a teenage girl can get in. Only, turns out, it’s the miss goody two shoes of the town who gets knocked up by the town doctor’s son, instead. It went to #6 on the country chart and #55 on the Billboard Hot 100. I would call that a hit song.

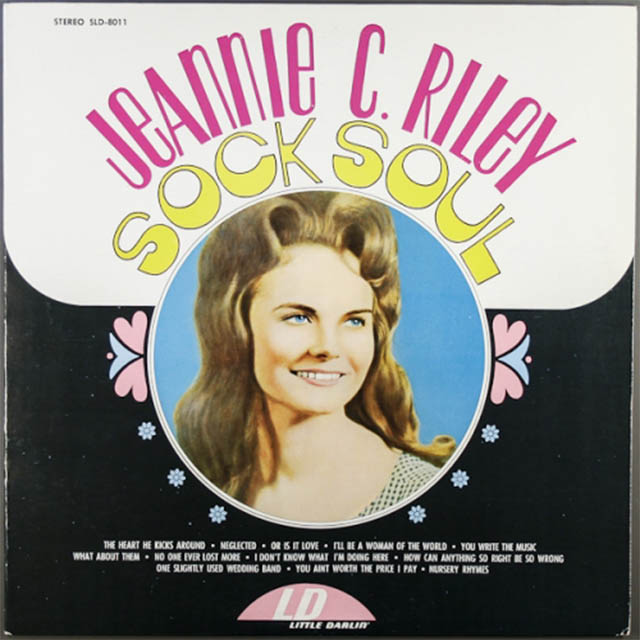

After that, Aubrey Mayhew put out an “album,” consisting of everything he had sung by Jeannie during her time with Little Darlin’. The album is called Sock Soul, I’m guessing, in reference to the line in “Harper Valley PTA” about how Mrs. Johnson socked it to ‘em. But this stuff was all recorded before anyone thought of Jeannie C. Riley as the loudest voice calling BS on American society, so none of the songs fit that album title or her image. The material is good. It’s just in the same vein being mined by every other female voice in country music. “The Price I Pay to Stay” barely cracked the country Top 40.

From there, her singles were hit or miss, if you judge them by commercial results. But even when she released a legitimate hit, nobody saw it that way because it wasn’t another “Harper Valley PTA.” Her first proper single released after that Little Darlin’ compilation (of, basically, demo recordings) was “There Never Was a Time.” It was a Top 5 country hit that also cracked the pop Hot 100. If you want to hear a great song from the same album, listen to the single, “The Back Side of Dallas.” It wasn’t a hit but it’s a damn good song.

Up until the mid-70s, the quality of her music remained pretty consistent. Her next Top Ten, “Country Girl,” shows her starting to branch away from the “Harper Valley PTA” prototype of getting on a microphone and pointing fingers at society. Also, letting Jeannie multi-track her own harmony vocals was a great way to shut up the critics who liked to say she had no range as a singer. And, of course, most of these critics were pop writers who were only aware of Jeannie C. Riley because of the pop success of “Harper Valley PTA” and whose only other frame of reference for country music in the ’60s and ’70s was probably Johnny Cash. Like the L.A. Times pop critic Robert Hilburn, who reviewed a Jeannie C. Riley concert in 1971, under the headline LITTLE TALENT: “Jeannie C. Riley has all the confidence in the world but, unfortunately, very little of the talent. First of all, her voice isn’t any good. Second, neither is her material. That’s two strikes against her. And, as soon as the public forgets Harper Valley PTA, that’s three strikes and she’s out.” [Please see the Liner Notes below the body of this post for accurate information regarding this review. Jeannie C. Riley, yet again, misrepresented the facts in her book.]

Now, maybe that guy was having a bad day or something but he doesn’t know what the hell he’s talking about. He’s wrong on every single point. From everything I’ve seen, Jeannie C. Riley was even better live than on recording. Make sure to check out the videos below for her performance of “Back Side of Dallas.” She always had a crack band behind her (the Harper Valley Express), they usually made the tempo of everything faster to really put some gas in the tank and it’s impossible to deny Jeannie’s charisma as a performer. The song she’s singing is about a woman becoming a prostitute and her expressions alternate between sassy and serious in a way that keeps shifting the meaning of the lyrics. Those charm school classes paid off. She knew how to work a crowd, striking poses and flashing 20 different kinds of smile in all the right places. But that LA Times review of her concert is the sort of dismissive attitude the pop intelligentsia had towards southern culture.

Not only was Jeannie not a one-hit wonder. She made good albums with very little filler. Check out the album track from 1972, never even released as a single, called “Without You.” Her voice is on, the melody is there – what more could you want from a country love song? It’s the kind of track you hope is waiting to surprise you when you buy someone’s album based on one or two of the singles.

“Without You” is from Jeannie’s second album on MGM, after leaving Plantation Records in 1972, in what Shelby Singleton called a breach of contract. Jeannie’s luck in the courtroom held, winning this case as well, though she maintained for the rest of her career that she was never paid what she believed she was owed for “Harper Valley PTA”‘s earnings.

Her full commitment to Christianity seems to have taken place sometime in the ’70s and seems to have caused at least some regret for her previous persona as country music’s most blatant sex symbol to date. The clothing changed, the music took a turn to gospel and, this is purely speculation on my part, but it looks to me like money could have really become a problem for her in the early 1980s.

That autobiography of hers was published in the year 1981, shortly before the release of a gospel album with the same title as the book. Generally speaking, when a musical artist “past their prime” puts out an album right after they put out a book, it’s safe to assume that book is meant to generate new interest in that artist’s music in advance of the new album. In other words, it’s often a promotional strategy. If that’s what happened here, then the only problem is this book was printed by a small publisher of Christian books. It may not be safe to assume that no major publishers were interested and that’s why Jeannie went with the small Christian publisher. However, it does seem very safe to assume that this small Christian publishing house would mostly, if not exclusively, have a promotional network meant to get their product in front of conservative Christians – a.k.a. the exact opposite audience of the only reason anyone knows Jeannie C. Riley’s name, “Harper Valley PTA,” a song highly critical of hypocrisy in social groups with hardcore conservative values. Even the music fans who did find the book wouldn’t be likely to recommend it to a friend because of how poorly it is written and how most of it is irrelevant to her career in music. People who bought the book because they happened to see it on one of their regular trips to the Christian bookstore would no doubt be scandalized by Jeannie’s rampant infidelity and the pot smoking. The used copy that I have once belonged to a library in New Mexico. It still has the stamp card in the back. I can see that only four people checked it out in 1981 (the year it was published), one person in 1982, nobody in 1983 and, one or two readers a year, at best, from there. It was discarded in 1995, having been checked out a grand total of 13 times. Not good, especially if that was the main plan to get people hyped for that new gospel album, which entirely failed to chart.

If she had hopes of getting off the road, where she seems to have been making most of her income, From Harper Valley to the Mountain Top as a book/album combo, did not deliver.

Next move?

Ask Tom T. Hall to write another “Harper Valley PTA,” a thing he’d been very vocal about his reluctance to do. But, also, he’s a big softie. It’s easy to imagine him having a hard time saying “no” when Jeannie came to him about it in 1984. Tom wrote “Return to Harper Valley” for her. He even made all the lyrics fit Jeannie’s new Christian lifestyle.

We’re back at Harper Valley High because our narrator’s grandchildren go to the school now and she’s bought a ticket to the raffle at a school dance. She’s wearing a dress that’s well below her knees because just about every character from the original song is now on the straight and narrow. But wouldn’t you know it? She spots a man giving a cigarette to a school kid and, it turns out, he’s selling drugs in the parking lot. There’s the drummer of the band doing cocaine and these kids are all getting drunk and taking pills and taking off their clothes. She thinks about going home for her gun but, instead, decides to go home, pray with her Bible and, you guessed it, bring all this up at the next meeting of the Harper Valley PTA.

In short, the song is terrible. Nobody cared, at all, even with Tom joining Jeannie for promo appearances on all the usual TV shows, like Nashville Now. There seems to have been a sense of urgency in the writing, recording and release of the song. Whatever the reason for the rush, and even if fans of the original song had grown to develop more conservative values, there simply wasn’t enough interest in this return to generate airplay or sales figures.

Seven years later, in 1991, Jeannie put out what looks like will be her final formally released single, “Here’s to the Cowboys.” The entire review in Billboard is one sentence long: Riley gives a poignant reading of this tribute to “cowboys” who are committed enough to be domesticated.

As some of you may have seen on Fox News in 2002. Somewhere along the line, she apparently forgot that she worked with the guy who was probably responsible for creating the “Elvis is still alive” rumors because she went on TV and told America that Elvis is still alive. His name is spelled wrong on that gravestone because Elvis was too honest of a man to put his name on a grave that doesn’t have him in it. She knows there are people in Nashville laughing at her and calling her crazy but she doesn’t have anything to lose.

Thank you for listening to (and reading) Cocaine & Rhinestones. This and every other episode of the podcast is written by me, Tyler Mahan Coe.

If you enjoyed this episode or even if you’re just excited about someone finally making a podcast dedicated to the history of country music, then, please, rate and review the show in whatever podcast directories you can find it. I will also ask that you, please, share this episode with one person in your life. If you know someone who would like this story but you know they hate podcasts or they can’t figure them out or whatever, send your friend to this blog post to read the story and, hey, maybe someday they’ll give the podcast a chance.

I hope you’re subscribed to the show because next week the “Harper Valley PTA” series is wrapping up with Tom T. Hall. I love Tom T. Hall. Based on how many people requested a Tom T. Hall episode as soon as I went public with this show, it’s safe to say a lot of you do, too. Of course, I had the whole first season written before I released an episode but I’ve got to say I was pretty surprised that Tom T. was such an instant demand from everyone. I thought I was just making an episode about one of my favorite songwriters. so I’m excited for all you other Tom T. Hall fans out there to get your eyes and ears on this one.

I don’t think I should put an ad in this episode, for obvious reasons, so what I’m going to do is tell you about the other podcast I’m doing. The other podcast is called Your Favorite Band Sucks. It’s exactly what it sounds like it is, a comedy podcast, more like other podcasts than this one. Cocaine & Rhinestones is very scripted, very produced. It takes me a long time to make these episodes. Your Favorite Band Sucks is the exact opposite. It’s just a show where my friend, Mark, and I sit down and say some of the worst things you will ever hear about bands that you probably love. It’s currently available in iTunes or you can go listen to it at YFBSpod.com. Our first three episodes are out now. We did an episode on The Beatles, an episode on The Rolling Stones and an episode on Christmas music. Enjoy

-TMC

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [linked, if available]:

- Billy Swan – “I Can Help” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jeannie C. Riley – “Good Enough to Be Your Wife” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Connie Smith – “Once a Day” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “A Good Year for the Roses” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Paycheck – “Lovin’ Machine” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Clark Bentley – “The Old Town Drunk” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jeannie C. Riley – “Harper Valley PTA” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jeanne C. Riley – “You Write the Music” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Glen Campbell & Jeanne C. Riley – “Pickin’ Wild Mountain Berries” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jeanne C. Riley – “The Girl Most Likely” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jeanne C. Riley – “The Price I Pay to Stay” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jeanne C. Riley – “There Never Was a Time” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jeanne C. Riley – “The Back Side of Dallas” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jeanne C. Riley – “Country Girl” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jeanne C. Riley – “Without You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jeanne C. Riley – “Return to Harper Valley” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jeanne C. Riley – “Here’s to the Cowboys” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Excerpted Video

These videos were excerpted and/or discussed in the episode. They may be removed from YouTube in the future (for any of a number of reasons) but, for now, here they are:

Commentary and Remaining Sources

I had no idea what I was in for when I began this episode and I’ll tell you right now that I have no idea what the truth is, here. I don’t even know what I’m really allowed to say right now but I guess if I’m going to get in trouble for this then I’ve probably already crossed that line…

I know there are lies in this episode because I told you which ones I found out about but I have no idea what else is or isn’t a lie. All I can tell you is that I did not knowingly perpetuate a lie.

When I’m reading a book, I pretty much always save the preface and foreword stuff until after I’ve read the book because there have been a few times, reading some classic novel or something, where the person writing the foreword, some scholar or someone, assumes everyone must have already read this book before and they drop major spoilers, right there, before you’ve even read the first page. So, out of habit, I just never read that stuff in the beginning of a book. If the book’s good, I’ll usually go back and read it. Or, if I’m just, like, “What the hell did I just read?” then I’ll go back and read it. That second scenario was very much the case with Jeannie C. Riley’s book.

By the second page of the book, when she was putting those words in Shelby Singleton’s mouth and it just didn’t seem to me like the way he talked and it didn’t make sense the way that she was having him act, based on other information she was giving us at the same time – I had a feeling something was up. Then, a little bit later she’s writing about having just married Mickey while she’s still in high school. This is a quote from the book, “Mickey and I moved into a small apartment and struggled each month to make it on his salary. We postponed going to Nashville until I graduated from high school and we could save some money. I was at the doctor’s office for a check-up when he told me he thought I was pregnant. ‘In another month we’ll know for sure, he said.’ Okay, I didn’t skip over anything there at all. She writes a sentence about waiting to move to Nashville until she graduates high school. Then, the very next sentence is about her finding out she’s pregnant. There’s a four year gap between those two sentences. I still have no idea why that gap is there but that’s when I knew I was reading some bullshit.

So, after finishing the book, I went back to read the stuff at the beginning and I found that disclaimer about the facts being altered. That disclaimer is written by Jeannie’s co-author, who I also failed to mention is a preacher. Here’s what he writes, “To keep from hurting some of the folks Jeannie loves, we have changed the names of several people in the book. In one instance we also changed the details slightly to purposefully disguise a scene. Only those who were involved will recognize what we have done. But all the rest is true – just as it happened when God picked up the Harper Valley girl and set her on a mountain top.”

Even that disclaimer is so entirely bizarre. The whole thing makes me wonder if this guy is even talking about inventing the character of Phil Blackman. First of all, they changed the names to protect people Jeannie loves? Jeannie “loves” the person who blackmailed her with revenge porn? Okay. Next, in “one instance” we have changed the details “slightly” to disguise “a scene”? That is not, at all, an accurate description of Phil Blackman’s existence in this book. There are many scenes that had a lot more than slight details changed, several that had to have been completely fabricated. Anywhere in the book she talks about the first Black Rose single is a lie. Talking about meeting Aubrey Mayhew in Las Vegas is a lie. Talking about getting out of a contract with Phil Blackman to record with Aubrey Mayhew is a lie. It would take me ten minutes to list everything that is for sure a lie and it would probably take me half an hour just to list everything I suspect is a lie in this book. Then, still with this disclaimer, the part at the end, where he writes “but all the rest is true”? He wasn’t there when all of this stuff happened. So, all that means is “this is what she told me happened.” That really makes me wonder if Jeannie came up with this whole Phil Blackman storyline on her own and tried to sell it to this guy as fact. Maybe he figured out she was lying so this disclaimer is his way of covering his own ass, in case, I don’t know, Aubrey Mayhew decided to sue the shit out of ’em. This is all, obviously, wild speculation on my part but, at this point, I’m not sure what other response I could possibly have to this pile of nonsense.

The attempt at disguising the truth is so clumsy that it even presents another possibility, which is that they wanted people to figure out the truth and have it blow up into this big controversy to sell the book. That certainly sounds like a business strategy someone might pick up from, say, working with Shelby Singleton. The only problem being that hardly anyone read this stupid book in the first place, so that didn’t happen.

There’s so much other stuff in that autobiography that I didn’t even get into. Definitely do buy this book, if you want to see a worst-case example of a country singer autobiography. I hadn’t yet been broken down enough by making this podcast to just start writing in the books I read or else whoever ends up with my copy of this one could have looked forward to some pretty intense scribbles all over it, I’m sure. Oh, yeah, by the way, I am giving away the books I read to make season 1 of this podcast. You could end up with my copy of this book with the library card in the back and everything – a real piece of podcast history.

Okay, all of this deception aside, I think we’re starting to get an idea of how differently all the people involved can come out the other side of a hit song. One thing that’s really interesting that we learned today is that, unlike Loretta Lynn’s recording of “The Pill,” the music establishment in Nashville (and everywhere else) mostly just got on board with this song right away. Tex Ritter did say that the song sounded “dirty” and “suggestive” and some radio stations did ban it but who cares? It won a Grammy award. It won CMA single of the year. Sure, the lyrics aren’t scandalous at all compared to “The Pill” but why do you think these two songs were received so differently by the old guard? I know what I think. I think money talks. I think that by the time any of those would-be buzzkills started paying attention, this song was already the #1 pop song in America and it went #1 pop before it went #1 country. Every major record label in Nashville had been falling all over itself for 15 years trying to do that. They’d have made Jeannie C. Riley the mayor of Nashville if she did it a second time. Her second single didn’t get there but they let her hang around a while to see if it happened again. It didn’t and this is the story we end up with.

By the way, I could also get into a whole other ramble about nature vs. nurture, here. You know, is Jeannie C. Riley “the way that she is now” because of everything that happened to her or was she always like that? I honestly don’t know.

After recording this episode, I was checking one more thing and I found a People magazine interview from 1981 that says Jeannie was broke by the mid-70s. So, I was a little late on my guess when I said it looked like money problems were there in the early ’80s but I was right, they were there.

If anyone even cares, Jeannie and Mickey did remarry, after a super long, who-gives-a-shit, “will they?, won’t they?” phase. In that same magazine article he’s quoted as saying, “She’s a little crazy. But she’s just a good ol’ country girl, really.”

Also, after recording this episode I found out that Jeannie C. Riley misquoted the LA Times critic Robert Hilburn in her book because of course she did. Also, the review was from 1969, so it makes so much more sense, knowing that it came from that time rather than two years later, in 1971, as Jeannie stated in the book. This is really aggravating for me because this is just my fault. This is my fault for not fact checking every minor detail of what I was using from a source that I knew was bad. Here’s what Robert actually wrote in his review, “Miss Riley has all the confidence in the world on stage but, unfortunately, little of the talent. Neither her voice nor most of her material (largely drawn from her two albums) is very good. That is two strikes. The day the public forgets ‘Harper Valley PTA’ may mean three.” The difference between what is written there and what I quoted in the episode may seem so small as to not be noticeable to some of you but it’s there and I do see it. My response in the episode to Jeannie’s version of this review is harsher than what it would have been if I was reacting to the real review. So, if Robert Hilburn happens to be reading this, I do apologize to you, sir. We may still disagree about something you wrote nearly 40 years ago but not nearly as strongly as I thought when reading and reacting to it second-hand.

Okay, there are no more books to talk about as sources for this one.

Come back next week. We’re putting this baby to bed. It’s the end of the “Harper Valley PTA” series. We’re talking Tom T. Hall on Cocaine & Rhinestones.