Two words to sum up the career of Shelby Singleton?

Publicity stunt.

You think all it takes to make a hit record is to find a good song and get a good performance of it?

That’s cute. Have a seat and let an old-school record man show you how it’s done. This is Shelby Singleton.

When it took driving a trunk full of records around the country to make them into hits, that’s what he did. Then he became a producer. Then he became a VP at Mercury Records. Then he founded an independent musical empire in Nashville and really got to work making new enemies.

This episode is recommended for fans of: marketing, publicity, controversy, rockabilly, Supermensch (the documentary on Shep Gordon), George Jones, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis Presley, David Allan Coe, Margie Singleton, Jeannie C. Riley and Roger Miller.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

In addition to The Library, these books were used for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

What’s Hit?

The earliest use of the word “hit” was as a verb: the act of happening upon a person or thing. We still use it this way to describe a fortunate meeting or locating the solution to a problem. We “hit it off” with a new friend at the bar. We “hit upon” the answer to a question that’s been bothering us.

At some point in the 15th or 16th century, it had been used enough to describe “hitting upon” one’s target in battle, that we started saying “hit” to describe physical assault. “The stranger insulted the man’s wife, so the man hit the stranger.”

It wasn’t really until the 1800s that the word “hit” started being applied to creative endeavors that performed well with an audience, the way we use it today to talk about movies, podcasts, songs, etc. “They’ve really got a hit on their hands with this one.”

You could say all of the original meanings of the word are there when we talk about a hit song. Broadly speaking, the creators of a hit song hit upon the correct arrangement of sound and words to give us what we want to hear. We, in turn, hit upon the song in the aisles of a music store or while skipping between stations or playlists. The physical sound waves actually hit our eardrums. And, if you’re listening to country music, then you may be inclined to hit the bottle in response to what you hear.

In other words, any hit song is really a series of hits. Even when we’re talking about a great singer/songwriter like Willie Nelson – one person, capable of writing the song himself and performing it himself in a way that millions of people will want to hear – well, there was someone who hit upon Willie when he was just a young songwriter or else we’d have never heard of him. Today, I want to talk about that type of someone, that type of hitmaker. Because the hit he made happen is one of the biggest in country music history…

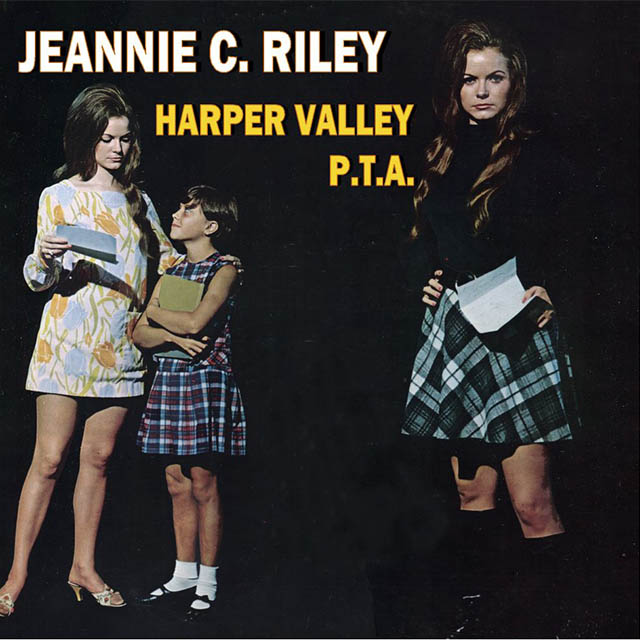

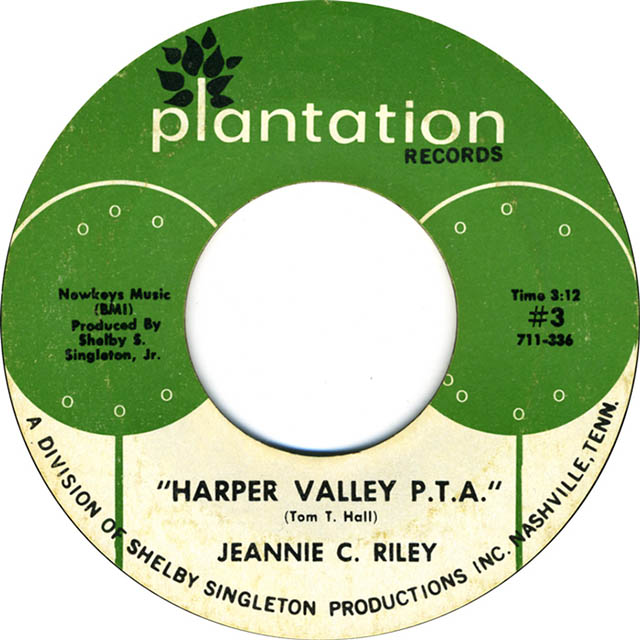

“Harper Valley PTA” isn’t a novelty song – but it’s close. We’re hearing the story from a student at Harper Valley High School and she’s been sent home with a note from the Harper Valley PTA about her young, widowed mother, Mrs. Johnson. The PTA, even though it’s none of their business, want Mrs. Johnson to know that they don’t approve of her wearing miniskirts and going on a lot of dates with men. Mrs. Johnson goes down to the PTA meeting, wearing one of her miniskirts, and, essentially, calls everyone out on their bullshit.

Now, the musicians on this are great players but what they’re playing here is not remarkable in any way. The vocal performance is hardly what you would call singing. Anyone could walk into a karaoke bar and do this just as good as the record. Nearly every person involved in making “Harper Valley PTA” has gone on record saying they were consciously trying to replicate Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billie Joe” from the year before. It makes a ton of sense once you start hearing it that way. Both of these songs have a bare-bones musical arrangement, featuring a “lead” instrument interacting with the vocal throughout – strings on “Ode to Billie Joe” and dobro on “Harper Valley PTA.” Where “Ode to Billie Joe” is more subtle in its condemnation of small town America (and you can listen to episode 4 of this podcast for more on that), “Harper Valley PTA” is 110% direct attitude. That’s what made it a hit.

This is a “fuck you” song and that’s what millions of people wanted to hear at the time because they were tired. Tired of the hypocrisy in everyday life. Tired of being told “do what I say, not what I do” by every authority figure. This is a time in America when the idea of protesting Western civilization itself was starting to gain serious traction. It’s the only explanation for how a song released on an independent record label in August of 1968 could make the biggest jump of the decade into the pop Top 10, from #81 to #7 in its second week on the Billboard Hot 100. By September 21st, it was the #1 pop song in America. By Sept. 28th, the #1 country song. That’s not people buying a record. That’s a feeding frenzy. This single sold 1.6 million copies within 10 days of being released and it just kept selling… 3 million… 5 million… Who knows where it’s at today?

They made a movie based on the song in 1978. That worked out so well, they turned it into a TV show that ran for two seasons, thirteen years after the single was a hit. A lot of you heard the song in season six of Mad Men. It’s safe to say it’s still bringing in major royalties.

I’ll get to Jeannie C. Riley, the girl who sang it. I’ll get to Tom T. Hall, the guy who wrote it. Today, I want to talk about the guy who made it happen.

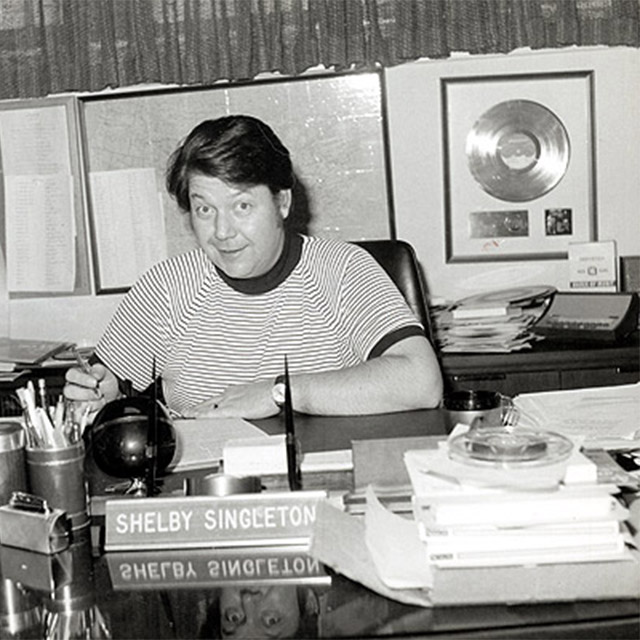

Good Times, Great Oldies

Readers of Paul Hemphill’s 1970 book, The Nashville Sound, may recall a scene where Paul is sitting in Shelby Singleton’s office, attempting to interview him while Shelby doesn’t even pretend to give his full attention to the situation. Instead, he’s sorting through his mail, answering calls on the phone and, generally, acting like a big shot, which, to be fair, he very much was. This scene takes place right in the middle of the aftermath of “Harper Valley PTA”’s explosion. Shelby’s segment of the book ends with him saying “goodbye” to Paul by telling him to make sure and write in his book that Shelby Singleton had 39 gold records before he ever laid eyes on Jeannie C. Riley. I don’t know if that number is exactly right but there’s certainly no reason to doubt it.

Shelby Singleton’s fortune in the record industry is enough to make you question if a rose really would be a rose by any other name. Singleton. It’s as if the man was born to put out hit singles. On the other hand, he may never have entered the music business, if not for his wife, Margie.

Margie and Shelby Singleton

Shelby was born in December of 1931 on the Texas side of the Texas/Louisiana border, near Shreveport. When he was 17, he married a 13-year-old girl, named Margaret. In 1949, there was nothing unusual about their ages. They had their first child together in 1950. Shelby had joined the Marines and, after his discharge, worked for Remington Rand in Shreveport, as an industrial engineer. They made typewriters, computers and, sometimes, weapons. That was Shelby’s day job but, on the side, he helped Margie pursue her interest in becoming a songwriter and a singer. Near Shreveport, the closest brass ring to reach for would have been the Louisiana Hayride.

The Louisiana Hayride was another one of these shows just beneath the Grand Ole Opry in terms of popularity and influence in country music. If you became one of the main attractions there, you were almost guaranteed a spot on the Opry if you wanted it. The Hayride program played a big role in the early careers of many major artists, like Hank Williams Sr., Elvis Presley, Webb Pierce and George Jones, who was the big star being made by the Hayride when Margie Singleton began coming around, in 1956 or 1957.

Margie Singleton on the Lousiana Hayride

The timing of all this is enough to make you dizzy, so stick with me. And, remember, if any of these things didn’t happen, “Harper Valley PTA” may never have happened. George Jones’ first single comes out on Starday Records in 1954. One of the founders of Starday is Pappy Daily, George’s first manager and his producer from that first single all the way until 1971. By 1957, around the time Margie started showing up on the Hayride, George Jones has four Top Ten country singles on Starday: “Why Baby Why,” “What Am I Worth,” “You Gotta Be My Baby” and “Just One More.” Mercury Records decides the solution to some problems they’ve been having is to merge their country roster with Starday’s to form a label called Mercury-Starday. The Starday people will sign and record country artists, who will then be distributed through Mercury’s much larger sales network. This deal goes into effect on January 1st of 1957.

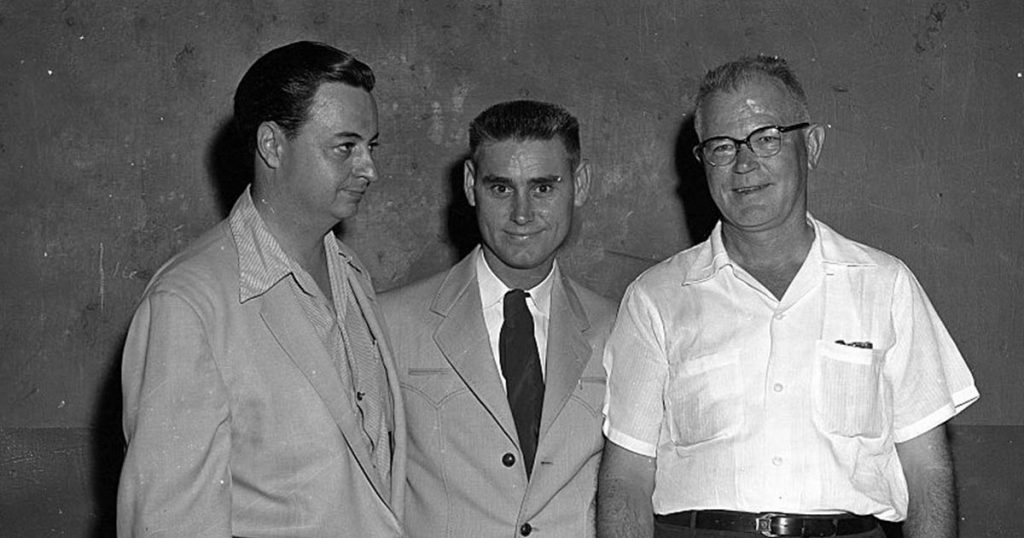

Hal Smith, George Jones & Pappy Daily

Now, when Margie Singleton started playing the Louisiana Hayride, Shelby Singleton and Pappy Daily became friends, which leads to Margie getting a record deal with Starday, not Mercury-Starday. Dailey’s partner at Starday, Don Pierce, is in charge of Sales and Promotion for Mercury-Starday and he hates Margie Singleton’s music: “I hated her records. Terrible!”

I’ve heard much worse than Margie’s first record on Starday, “One Step Nearer to You.” In fact, I think it’s pretty great. I think Don Pierce’s problems with Margie are that he’s, personally, a country music purist and his job is to push country music in a time when rockabilly is more popular. A lot of Margie’s early stuff is rockabilly, like 1958’s “Teddy.” With Margie signed to Starday and not the higher priority Mercury-Starday, she isn’t really Don’s problem. So, he doesn’t make a big deal out of not liking her music, which is good, because it turns out his new workload is much bigger then he’d expected.

Mercury does not want Don to only promote Mercury-Starday records. They want him to promote the entire Mercury catalog, every genre, in addition to all the other stuff he’s supposed to be doing. They clearly need to hire someone whose only job is promotion. That’s how Shelby Singleton gets his first real job in the music business, in October of 1957, working closely with Don Pierce as Southern Promotions manager for Mercury. This, essentially, means driving boxes of records around to people who can turn them into hits – radio programmers, distributors, DJs, etc. – and, in Shelby’s words, staying up for two or three days and outdrinking everybody. Good times, great oldies.

Don Pierce outside Mercury-Starday’s Hendersonville, TN office

Shelby and Don spend a lot of time together on the road, with Don unloading all his wisdom onto Shelby. Like, how you should never stop at a restaurant that advertises ice cream. Instead, stop at a restaurant that advertises liquor because liquor makes more money so they can afford to buy better quality food. I’m not so sure that’s the way it works.

Either way, by August of 1958, Mercury-Starday is no more.

The label hasn’t produced any more hit makers like George Jones, so Mercury keeps George, a few other artists, Pappy Daily and Shelby Singleton. Half of the Starday catalog and the Starday name are left with Don Pierce. Mercury-Starday existed for only 18 months but, if it hadn’t happened, then we might not be talking about “Harper Valley PTA” today because we might not be talking about Shelby Singleton – even though it’s hard to imagine a world without Shelby working in the music business. He’s a natural for promotion, just extremely good at his job, and he very quickly moves up the ladder at Mercury. When a producer can’t make his session, due to a snowstorm in Chicago, Mercury tells Shelby to produce the session himself. He does so great, that gets added to his job description. His first side to hit is Brooke Benton’s cut of “The Boll Weevil Song,” recorded in 1960 and a #2 pop song in 1961.

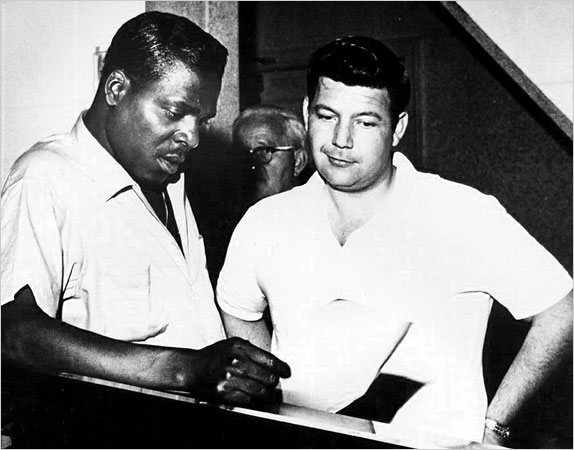

Brook Benton with Shelby

We’re Gonna Get Rich & Be Famous

When Shelby produces a session for Mercury, it’s often in Nashville. He makes the trip up from Shreveport, usually bringing a kid named Jerry Kennedy with him to play on the session. Jerry had played guitar for Faron Young, Johnny Horton and in the house band at the Louisiana Hayride. Shelby likes the way he plays and they get along well. For Shelby, who’s not a musician, Jerry serves as something like a musical translator for what Shelby wants other musicians to do on a song. It’s a hit-making partnership.

In 1961, Shelby’s promoted to head up the office Mercury opened in Nashville during the Starday merger. Shelby talks Jerry Kennedy into moving up there, too. Jerry remembers he didn’t want to move to Nashville at all, “Shelby talked me into it and, against everything I believed in, I came up here to try it. He told me we were gonna get rich and be famous.”

Shelby wasn’t lying to Jerry and the move works out well for Margie Singleton, too. She and Shelby would get divorced about three years after this but not before Margie got signed to Mercury and cut some hits. In 1962, the second duet between Margie and George Jones goes to #11, “Waltz of the Angels.” A couple years later, she hits #5 with Faron Young.

Shelby (left) and Jerry Kennedy (seated w/ guitar)

By 1962, Shelby is a Vice President at Mercury Records – overseeing operations for Mercury and at least two subsidiary labels, splitting his time between New York City and Nashville and producing hits for artists, like Clyde McPhatter, Leroy Van Dyke, Joe Dowell and Ray Stevens. It’s around this time that Shelby instigates one of the most infamous pranks in the history of the entire music business. If you haven’t heard the one about Quincy Jones’ first visit to Nashville, get ready to be uncomfortable.

In the record industry, you go where the work takes you. That’s why Shelby was splitting his time between Nashville and New York City. Quincy Jones and Shelby had worked together quite a bit and there came a time when it made more sense for Quincy to come down to Nashville for a session than for that session to go to him. If you’re unaware, Quincy is a black man from Chicago whose parents moved out of the South before he was born. This being the early ’60s, he was pretty nervous about going to Nashville. Talking about it with his black friends and hearing their horror stories made him even more nervous. I’m going to tell the rest of this with a quote from Jerry Kennedy but his version is fundamentally identical to any other that I’ve read or heard over the years.

Shelby sent out and got sheets and pillowcases for all the musicians – to wear. I still remember Quincy’s face when he came in and saw all these musicians sitting with their instruments ready to play, in white sheets and pillowcases. It was just a great way to break the ice. In fact, for years Quincy told the story all over the place too. I was one of the first people he saw when I came out from under the sheet and he cracked up. – Jerry Kennedy

Now, if you somehow have no idea what he’s talking about there, members of the KKK, a white supremacist organization responsible for countless hate crimes and murders, used to hide their identities under pillowcases. It’s possible that Quincy didn’t think that was as funny as Jerry says he did. Or, at least, Jerry may be underplaying Quincy’s fear before the reveal to make it seem more like a harmless prank.

Shelby’s version from another source that doesn’t mention Quincy by name, “I was the only one in there that didn’t have a hood on. He came running at me and grabbed me around the neck saying ‘What’s happening? What’s happening?'” It’s also possible Shelby is exaggerating there and Quincy really did laugh about the joke. Maybe they had that kind of friendship. I honestly have no idea.

Shelby & Quincy Jones (right) at a party for Lesley Gore

There is no indication that Shelby ever pulled something like this with anyone else and Quincy probably wasn’t even one of the first one hundred black people he’d recorded with by this point. In fact, Nashville was still segregated in the early ’60s. There really were people who would have been angry to learn that white and black musicians were working together in recording studios. Shelby was clearly not one of them. There was at least one black hotel in Nashville at the time but when black musicians or producers like Clyde McPhatter or Quincy Jones came to Nashville to work with Shelby, they were invited, even encouraged, to stay with Shelby in his home. Being a persuasive man, I’m sure most of them took him up on the offer.

Shelby talked Ray Stevens into moving to Nashville by offering him a job as a gopher and giving him his first session work as a piano player. One night, Shelby was eating at a diner in Printer’s Alley (in Nashville) with some Mercury executives. They noticed Roger Miller sitting in a corner across the room. Now, Roger was signed to RCA but the word around town was that he didn’t think they were handling him the right way. Someone at Shelby’s table said they should try to sign Roger to Mercury. So, Shelby got up, walked over there and came back in less than a minute saying, “Yeah. We got a deal.” Roger Miller was signed to one of Mercury’s labels, Smash, where he would have most of his “smash” hits in the ’60s – “Dang Me,” “Chug a Lug,” “England Swings,” “Engine Engine #9,” “King of the Road,” you get the point – and most of those hits were produced by Shelby’s right hand man, Jerry Kennedy.

A Single Corporate Entity

At some point, Shelby must have taken a look around and realized how much work he was doing just to get a piece of what he was bringing in for Mercury. In 1966 (a year or so after divorcing Margie, by the way), Shelby resigned and began building his own empire, The Shelby Singleton Corporation.

He’d hustled his way from the bottom, all the way to the top. There wasn’t anything that Shelby didn’t know about the record industry.

One thing you would do is have a single corporate entity release music as several different labels. It would essentially be the same crew working on everything behind the scenes but R&B got released on this label, country songs on that label and so on. It was about the label, literally – like, the actual, physical label that would go on the records. By building each label around a specific genre, that label would develop an identity and reputation in that genre. Say you had monster hit on a little blues label. Three months later, a DJ could see a new record with that label’s label on it and know this might be the next monster blues hit. If you’ve got big band jazz, blues, rock, pop and soul all showing up looking like the same thing, that specialty reputation will never be there. So, The Shelby Singleton Corporation was not a record label. It was a parent company, a corporate umbrella, under which many record labels would come to live, as well as recording studios, a management agency, an advertising agency, a film production company, on and on and on…

But, at the beginning, two of Shelby’s first labels were SSS International and Plantation. SSS (Shelby’s initials, by the way) was for R&B music. Plantation was for country music.

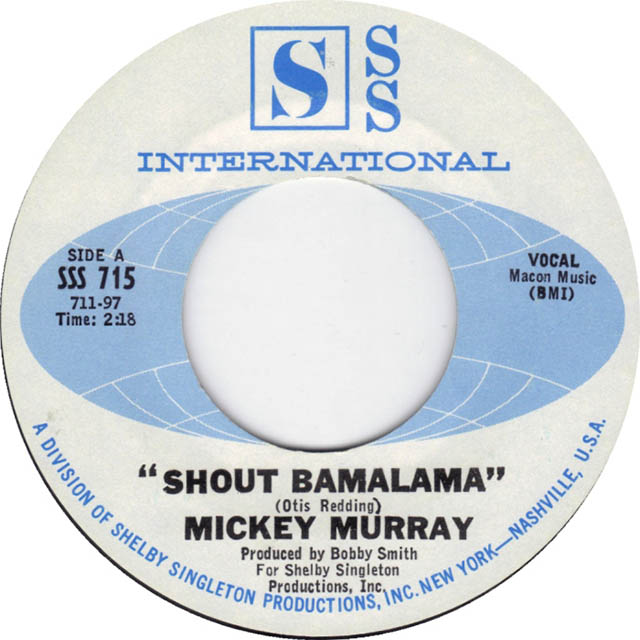

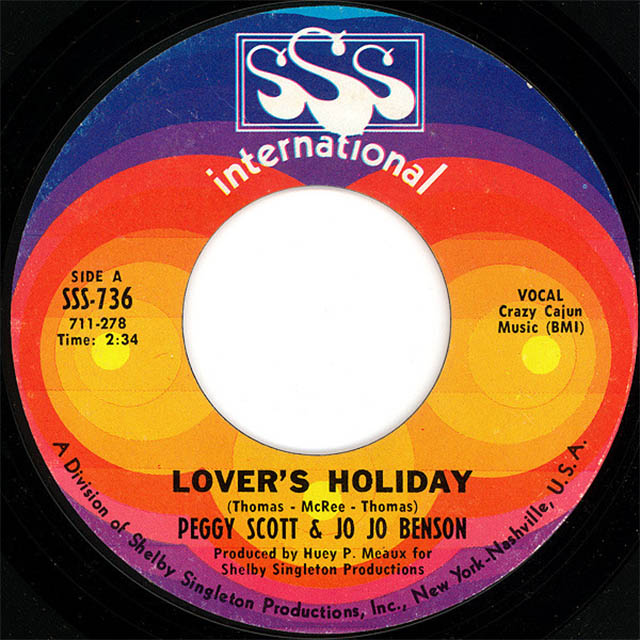

SSS International’s first minor hit was Mickey Murray’s cover of Otis Redding’s “Shout Bamalama” in 1967. Spring of 1968 brought a Top 40 record in Peggy Scott & Jo Jo Benson’s “Lover’s Holiday,” which reportedly sold 900,000 copies.

When Shelby turned his attention to country music, the first single released on Plantation Records ended up being “Flag Draped Coffin” by Tom Sawyer, an example of the “fallen soldier” sub-genre of miserably sad country songs about Vietnam. The second single released on Plantation was “Big Fanny” by Neil Ray, a truly bizarre song about a disgusting behemoth of a woman who fought the Viet Cong, fought a grizzly bear, then went back to Vietnam to fight more VC. If you’re sensing a pattern here, you may be starting to understand Shelby Singleton.

Without Mercury’s big machine behind him, Shelby leaned hard into any sort of gimmick that might help him out on the marketing/PR front. Here, in the second half of this episode, you may start to get an idea of Shelby as sort-of the PT Barnum of the Record Business. I would say that’s accurate because Shelby was willing to go one step further than the next guy but these Hail Mary stunts for exposure are highly typical of entertainment industry types. In other words, the music business is full of PT Barnums. The only thing that separates Shelby from the pack of guys like Shep Gordon is that one step further Shelby was willing to take. Because Shelby was never afraid of a little controversy… or a lot of controversy. Check his production credentials and you’ll see Shelby was in the control room for Ray Steven’s 1962 Top 5 pop hit novelty, “Ahab the Arab,” a song you’d have to be certifiably insane to try and record for a major label today.

So, those first two Plantation singles didn’t find a home on any side of the Vietnam zeitgeist but the third time’s the charm. Shelby got it right on Plantation’s third single by broadening his scope and aiming at something an entire generation could get on board with: condemning the hypocrisy in small town social politics.

According to Shelby, he kept a demo tape of “Harper Valley PTA” in the drawer of his desk for at least six months. The singer on the demo was a girl named Alice Joy. Shelby knew there was something in the song but he didn’t think Alice was right for it. You can try to imagine her version if you want by listening to the a-side of what may be Alice Joy’s only single ever, “He’s Coming Back to Me,” from Ashley Records in 1967.

Shelby never explicitly said what kind of singer he was looking for to do the song but, based on a couple quotes from later on, we can put it together: not so much a singer as a voice, not so much an artist as an attitude, not so much a person as a caricature.

A disc jockey friend of mine was managing a girl named Jeannie C. Riley. He brought me a demo of her singing. ‘Bring her by here,’ I said. ‘I’ve got a song that I think is a hit if she’s got the right image that I want to sing this song.’ – Shelby Singleton

Funny way to put that, don’t you think? The right “image” to “sing” this song?

Alright, so, you know how slasher horror films have certain rules for survival? Never open the closet door. Don’t drink or do drugs or have sex at the big party. The main character will be a popular girl who’s too pure to go all the way with her boyfriend and she’s the one who survives to the end and defeats the killer, right? Okay, well, if this is a slasher movie, then a young Jeannie C. Riley looks like that girl’s best friend, who gets killed in the backseat of a car with a guy in the first scene. And it’s safe to say that’s what Shelby Singleton’s looking for because, as soon as he gets a look at Jeannie C. Riley, the wheels are put in motion.

Jeannie C. Riley

They schedule the Nashville A-Team for the session: Buddy Harman on drums, Bob Moore on bass, Shelby’s old pal, Jerry Kennedy, on dobro and, possibly, Harold Bradley, Ray Edenton or Chip Young on guitar – plus Pig Robbins on that organ that comes in for the dramatic key change. Pete Drake is also booked for the session but I don’t hear any steel guitar in this song, unless that’s him buried in the mix in the right channel.

Here’s another quote from Shelby Singleton, “That night we knew the record was a hit but we didn’t realize how big it really was. You know it’s a hit when you’re staying around after a session, playing back takes, and all the musicians stay, too. None of them leave. They keep listening to it over and over.”

According to Jerry Kennedy, Shelby has an acetate of the session made right then and takes it over to WSM. Ralph Emery’s late-night radio show has an open door policy for artists, songwriters and cool industry types. Legend has it, he’s the first to play the song, on the same Friday night it’s recorded, and, by Monday, it’s a monster hit. Recorded in August of 1968, Harper Valley PTA is #1 in September. Shelby takes out a loan from a bank in order to print enough records to meet the demand. He makes it back and then some, grossing somewhere between five to seven million dollars in the first year but he also knows he’ll end up paying a ridiculous amount of income tax if he doesn’t find a way to dump that money into acquiring assets. Knowing the value of song catalogs, he starts buying up everything he can, as fast as he can. The Shelby Singleton Corporation absorbs publishing houses and record labels of any and every kind. He even buys Sun Records from Sam Phillips.

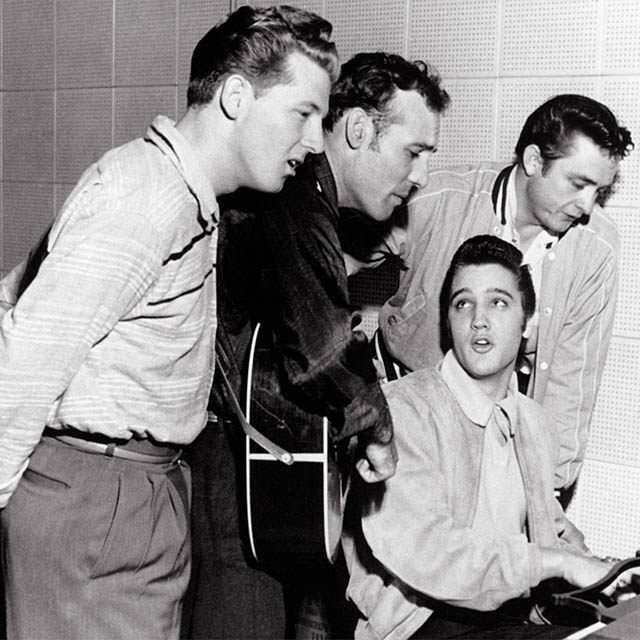

Now, Sun Records is far too big of a subject to fully get into here and I’m sure you know enough about it anyway. But, just to cover my bases, it’s the independent Memphis label where Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison and Jerry Lee Lewis all got their start. It also gave us two incomparable record producers in Cowboy Jack Clement and Billy Sherrill. Shelby Singleton and Sun Records founder, Sam Phillips, go way back. Shelby had tried to get Sam to sell Sun to Mercury for years, starting in the early ’60s. That’s another story, all in itself, but the two became friends (sort of) and, on a phone call in December of 1968, they set up a meeting. In July of 1969, for $1,000,000, Shelby Singleton becomes 80% owner of Sun Records.

Shelby and Sam Phillips signing the papers

The Vault

What Shelby bought when he bought a controlling share of Sun Records wasn’t just a roster of artists or the right to put Sun labels on records by whoever he was working with. What he bought was the master tapes of pretty much everything Sun had ever recorded, except for the tapes of Elvis Presley, which had already been sold to RCA Victor. This includes music already released by Sun, as well as everything deemed unworthy of release by Sun at the time it was recorded – music that had been shelved and forgotten about by Sam Phillips.

For one thing, it’s a treasure trove of unreleased rockabilly. This 1950s genre has a comeback in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Shelby Singleton is the only guy around with unreleased, first wave rockabilly from the Sun Records vault. Like Warren Smith’s classic, “Uranium Rock,” recorded in 1958 and unreleased until 15 years later in 1973.

But that’s not all that’s in this vault.

Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison, Charlie Rich, Jerry Lee Lewis – these guys recorded for Sam Phillips for several years at the beginning of their careers. Since that time, they’ve all gone on to become world famous recording artists. Sessions that Sam Phillips hadn’t felt were up to par back in the ’50s, these things are now worth thousand of times their weight in gold. Shelby starts putting out previously unreleased singles from artists who are now signed to major labels that Shelby has nothing to do with. He repackages their old hits into greatest hits collection after greatest hits collection. It pisses off a lot of people, for many different reasons. Say one of these artists puts out a new album with their current label and has a hit. This artist is out there, doing all the things artists do to promote that current hit. Our boy, Shelby, can slap a greatest hits tracklist together, give it a slick looking cover and get it on record store shelves with a sticker calling it the “NEW COLLECTION OF HITS” from that artist. Everyone finding out about this person for the first time can play catchup by buying this greatest hits. Shelby doesn’t even have to buy advertising because the major label that artist is on now has already dumped thousands into getting their face all over the place.

Here’s a specific example: We all know Johnny Cash’s song “Get Rhythm,” right? Well, that song was originally released on Sun Records in 1956 as the b-side to “I Walk the Line.” In 1969, a year after Johnny Cash’s live At Folsom Prison album and the same year as his live At San Quentin album, Shelby takes that Sun Records tape of “Get Rhythm,” adds in the sounds of a cheering crowd to make it sound like a live recording and puts that out as a single. People assume it’s from one of Johnny Cash’s wildly popular prison albums and it goes to #60 on the pop charts. I guarantee you that Shelby Singleton made some enemies by doing that and he definitely did not give a fuck.

Having Sun’s back catalog at his disposal is also the explanation for how, when “Harper Valley PTA” is made into a feature film in 1978, starring I Dream of Genie’s Barbara Eden, Shelby is able to stack the soundtrack with songs like “High School Confidential” by Jerry Lee Lewis and “Ballad of a Teenage Queen” by Johnny Cash. The movie is such a hit, they begin working on a TV series, also starring Barbara Eden, right away.

Business as Usual

Where many people would have been content to retire and live off “Harper Valley PTA” money for the rest of their lives, Shelby is a hustler. He doesn’t know anything except the game and he never stops trying to do the biggest thing he’s ever done. Repackaging old Sun material is a favorite project of his but he keeps making moves with his other labels as well.

Plantation Records, in particular, now has some serious weight to throw around. “Harper Valley PTA” did very well by playing into a social attitude that was popular at the time, so Shelby keeps up a steady stream of releases that seem to take one sort of position or another on quite potentially controversial social issues – war, race, religion. Pretty much anything is fair game and Plantation releases songs that play to both sides of these fences because each side has money. For example, as you heard a couple of episodes before this, Capitol Records talked Merle Haggard out of releasing an interracial love song (“Irma Jackson”) as a single. When word gets out about this, Shelby rushes out a version by one of his own artists, Dee Mullins.

It looks like Shelby’s biggest move for Plantation after “Harper Valley PTA” was to try and break the first female black country superstar, Linda Martell. Charley Pride had already hit in 1966, so why not? It looks like there was a lot of time and money put in to Linda Martell. I found a five-page spread in the March 1970 issue of Ebony. It’s loaded with pictures of Linda hitting all of the “next big thing out of Nashville” checkpoints – wearing a (presumably) custom-made rhinestone suit, being interviewed by Ralph Emery, getting introduced on the Grand Ole Opry by Roy Acuff, everything everyone does on the way to the top, everything Jeannie C. Riley did in her victory lap after “Harper Valley PTA.” In fact, there’s a picture of Linda hanging out with Jeannie, as if to say, “Get ready, folks. Here comes the next Plantation superstar.”

Roy Acuff with Linda Martell on the Grand Old Opry

Linda’s album, Color Me Country – yeah, the title is a little on the nose – but the music is very good. Her first single goes to #25 country. It’s a cover of an amazing soul song by a group named The Winstons, “Color Him Father.” The next single, a pre-Freddy Fender version of “Before the Next Teardrop Falls,” doesn’t do as good. Third single does worse. Her fourth, “Bad Case of the Blues,” does nothing, despite some – and I can’t believe I’m about to say this – some really good yodeling.

But don’t think Shelby didn’t hedge his bets with the other side of this coin. Black girl on the country label? White guy on the R&B label.

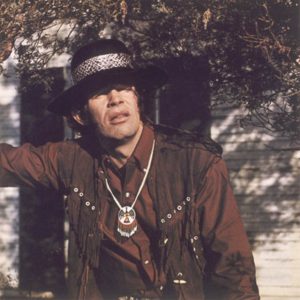

David Allan Coe

David Allan Coe’s first album, Penitentiary Blues, comes out on SSS International the same year as Linda Martell’s album – also first-rate stuff, also failed to really gain an audience at the time. But David Allan Coe would go on to play a big role in the history of country music and Shelby Singleton deserves some credit for that. Penitentiary Blues has since been rediscovered by David Allan Coe fans and is today regarded as a classic album.

These are two examples of slightly gimmicky things that were actually really good and just didn’t work at the time. A lot of what came out on Plantation after this is gimmicky to a fault. It’s difficult to find any value, here.

Like, it’s hard to imagine how anyone ever thought T. Tommy Cutrer’s “The School Bus” needed to exist, at all. It’s a song about a small town whose own schoolhouse now stands in ruins because they were forced to get a school bus and send their kids over the river to an integrated school “where the races were combined.” Well, they couldn’t afford anything but a dinky, old, used bus but they bought it and, then, one rainy night, that bus careened off the bridge and the child passengers all drowned. So, now, all the kids in this town are dead – all the white kids and all the black kids – and, if you can’t blame affirmative action, then who can you blame? The song ends with a chorus of, I assume, ghost children, singing “My Country ‘Tis of Thee.” Truly tasteless stuff. And that’s just one example of how far Shelby would go to try to push society’s buttons and get a hit.

His belief that anything was fair game in the pursuit of publicity entered a whole new realm of weird when Elvis Presley died.

Hail to the King, Baby

Now, it probably always bothered Shelby that he wasn’t really allowed to make money off of the music Elvis recorded for Sun Records. He could and did print up t-shirts and hats with an image of an Elvis record that had been released on Sun but he couldn’t use any Elvis tapes so he didn’t even bother with looking for them.

Until Elvis dies in 1977.

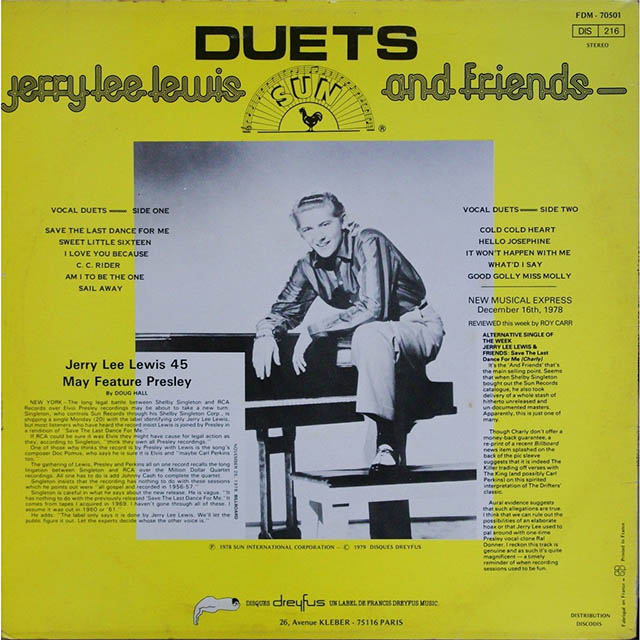

Shelby puts out a documentary with a little bit of Elvis music in it and gets sued by RCA. Then, he finds the Million Dollar Quartet tapes, a recording from 1956 that’s supposed to have Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins and Elvis Presley messing around together with some songs in Sun studio. Shelby immediately goes to court to fight for his right to release this tape.

Meanwhile, he’s up to his old tricks with the tapes he is allowed to use. Five years earlier, in 1972, he’d released a couple of old Elvis covers sung by a kid who would probably not like me to call him an Elvis impersonator but that’s what I’m gonna do, named Jimmy Ellis. Some of the labels on the record were printed with no name where the artist’s name would typically be, causing some fans and some critics to speculate that it was low-key really Elvis singing. So, when Elvis dies, Shelby reissues those Jimmy Ellis covers, again with no artist name on the label. Again, some people assume it’s an old Elvis recording and Sun just can’t put Elvis’ name on it for legal reasons.

In November of 1977, Sun puts out two Christmas songs by a different guy trying to sing like Elvis and, this time, there’s a big question mark where the artist name should be on the label. But, this guy? Not as good. No Elvis fan would believe this is Elvis.

Then, Shelby decides to stop fucking around.

He takes some old Jerry Lee Lewis tapes that he’s allowed to use and brings Jimmy Ellis back in to sing like Elvis on those recordings. Shelby releases this in 1978, as an album called Duets, credited to Jerry Lee Lewis and Friends. The liner notes don’t say who these “friends” are and, in fact, go to great lengths to stoke the imagination that this could really be Elvis singing with Jerry Lee Lewis.

Then, shit gets weird.

There’s a pretty crazy documentary on what I’m about to tell you, called Orion: The Man Who Would Be King. Here’s part of it. Some Elvis fan had written a novel, called Orion, about an Elvis Presley-ish rockstar who decided to fake his own death. Next thing you know, Jimmy Ellis is wearing an oversized, Lone Ranger-type eye mask that covers approximately half his face, calling himself “Orion,” putting out records on Elvis Presley’s first record label, Sun Records, and refusing to directly say “no” when the media asks if he’s secretly Elvis Presley.

“Orion” & Shelby

Now, if you’ve ever wondered why so many people, to this day, believe that Elvis Presley is really alive? I’m here to tell you, I think Shelby Singleton might deserve credit for that, too. His role in this charade freaked out even some people you probably think are un-freak-out-able. Here’s a David Allan Coe quote from a 1980 interview with Alanna Nash:

I have another friend named Jim Owen who does a Hank Williams impersonation show and it’s scary sometimes. Shelby Singleton is like my foster father and Shelby has a kid named Orion who sounds so much like Presley it’s frightening. Well, Shelby cut a song with Orion and Jim Owen called “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” right? So he’s got Orion singin’ like Presley and he’s got Jim Owen singin’ like Hank. And it’s scary! It’s almost like them two suckers have come out of the grave and are talkin’ to you. It just brought chill bumps all over me. And I said, “Man, you all are messin’ around with these people’s corpses. There’s gonna be somethin’ bad happen here eventually.” – David Allan Coe

One of the few men to ever live who could take a gimmick too far for David Allan Coe. That’s saying something. That’s Shelby Singleton.

Thank you for listening to (and reading) Cocaine & Rhinestones. Every episode is written and produced by me, Tyler Mahan Coe. Make sure to checkout the Season 1 Giveaway, if you’d like to have a chance for me to mail you my copy of one of the books I read for the show. If you’re enjoying the show, please, leave a good review on whatever app you’re using to listen because that really does a lot to let people who are looking for a new podcast know that this one may be worth their time.

I will ask you to, please, tell one person about this episode. You’ve got to know a George Jones fan, a rockabilly fan, an Elvis fan, a Sun records fan – any of those people.

This episode is supported by Midnight Rider. Midnight Rider proudly makes licensed classic country music merchandise in the USA on the softest of tee shirts – featuring musicians like Waylon Jennings, Johnny Paycheck, Townes Van Zandt, among others like ZZ Top and Janis Joplin. Check out www.shopmidnightrider.com for their men’s and women’s comfortable tees. Listen, I’ve got to own 7 or 8 of these shirts by now. They’re some of my favorite t-shirts. If you’re doing Christmas shopping right now, this will make an amazing present for anyone who’s a fan of any of the artists they have t-shirts for – get your order in by December 17th if it’s a Christmas present for someone.

Next week on the podcast, it’s the continuing saga of “Harper Valley PTA.” We’re talking about Jeannie C. Riley and I’m just gonna come right out and say it: I think I found something. I think I found something in this story that nobody else has ever found because I can’t find anyone else who’s ever talked about it. And, I’m going to try my absolute hardest to give you the real story without getting sued but you need to make sure you’re subscribed to this podcast. Because I’m not a lawyer, I’m dumb enough to not have consulted one and I honestly do not know how long the next episode is going to be allowed to remain online.

So, come back next week. Let’s find out what happens.

-TMC

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [linked, if available]:

- Jeannie C. Riley – “Harper Valley PTA” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “No Money in This Deal” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Margie Singleton – “One Step Nearer to You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Margie Singleton – “Teddy” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Brook Benton – “Boll Weevil Song” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones & Margie Singleton – “Waltz of the Angels” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Roger Miller – “Engine Engine No. 9” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Mickey Murray – “Shout Bamalama” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Peggy Scott & Jo Jo Benson – “Lover’s Holiday” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom Sawyer – “Flag Draped Coffin” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Neil Ray – “Big Fanny” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Alice Joy – “He’s Coming Back to Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Warren Smith – “Uranium Rock” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Cash – “Get Rhythm” (“live”) [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dee Mullins – “Irma Jackson” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Linda Martell – “Color Him Father” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Linda Martell – “Before the Next Teardrop Falls” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Linda Martell – “Bad Case of the Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- David Allan Coe – “Death Row” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- T. Tommy Cutrer – “The School Bus” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Million Dollar Quartet – “Blessed Jesus (Hold My Hand)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jimmy Ellis – “Blue Moon of Kentucky” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- ? – “Don’t Cry for Christmas” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jerry Lee Lewis & Jimmy Ellis – “Save the Last Dance for Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Orion – “Honey” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jimmy Ellis & Jim Owen – “So Lonesome I Could Cry” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Commentary and Remaining Sources

As I said at the beginning, I don’t believe there’s any such thing as “the” story of a hit song. Every piece connects to so many other pieces. Every hit song has so many stories to go with it but the story of “Harper Valley PTA,” for me, is one that really brings out the “what if” questions. You know, change one thing and what timeline are we living in then? This song needed so many things to come together for it to happen and so many things happened as a result of how huge it was. You can go deep into The Butterfly Effect with this one. Just change one thing. Say, if Shelby Singleton got behind Alice Joy singing “Harper Valley PTA” instead of waiting to find Jeannie C. Riley, what would happen then? Does the song become a hit still? Does Jeannie C. Riley ever make it? Or, go back further than that and ask if the Mercury-Starday merger – which seems like it was never even a good idea in the first place – if that wasn’t a thing for just 18 months of time on this planet, how much does that change of what has happened since? Shelby told Paul Hemphill that he had 39 gold records before Jeannie C. Riley came into his life. Every one of those gold records was a hit. How many stories are there behind each individual one of those? Are you starting to feel like you smoked a joint yet? It’s mind-boggling.

For everyone who doesn’t already know, David Allan Coe is my father. Naturally, I’ve had a lot of people ask me when I’m going to do an episode of Cocaine & Rhinestones on David Allan Coe. I’ll tell you, straight-up, I don’t know if that’s possible. I don’t know. The biggest reason is that I don’t know if I could approach that episode with the same objectivity I give to any other artist. It wouldn’t be fair to anyone involved, including you. There are several other reasons why it would be more trouble than it would be worth for me to do it and I’m not saying it’s out of the question – it’s not a priority at this point. I have a very clear vision of the timeline for this story I’m telling, at least through the next two seasons. David Allan Coe is not a main character yet, although, he may pop up in a supporting role from time to time like he did here, which, by the way, I was not expecting at all when I went into this episode.

Of course, what all of that means is, I did know Shelby Singleton. It’s crazy to go back and look at pictures of him when he was a younger man – this big, powerful figure. By the time I knew him, he had already grown small with old age. But he always had the trunk of his Cadillac full of Sun records swag. I can’t tell you how many Sun hats and shirts and whatever else I ended up with over the years. That old school record promoter inside of him never died.

Shelby did pass away in 2009. He was 77 years old. After they gave him the diagnosis of terminal cancer, he went out and bought a Rolls-Royce because he always wanted one and he knew that it was now or never.

That Quincy Jones story was not fun for me to tell. The only other detail I can add here is a quote from Buddy Killen, who was also there, also under a pillowcase, “Jones laughed a lot about the joke but only after he stopped gasping from the shock.”

I do want to emphasize that I was being sincere when I said I have no idea what kind of friendship Quincy Jones and Shelby Singleton had. Regardless of what kind of jokes they did share, what Shelby did in this specific instance was inherently racist. I don’t see how there could be any question about that. He would never do this to a white man because there would be no point, ergo, it is racist. I did run a lot of searches for things like “Shelby Singleton” + “racist, racism, KKK,” etc. – just to see if there was more to this than “it was the early ’60s and everyone acted like idiots.” There really does not seem to be anything more there. There’s a quote from Linda Martell talking about Shelby making the decision to put Linda on the Plantation label. Linda remembers that Shelby said something to the effect of, “We’ll put her on Plantation. She’s a black artist. That’s a selling point.” That’s really what it always came down to with Shelby: will this sell?

Linda Martell was actually the first black female artist to perform on the Grand Ole Opry. I didn’t mention that. I should also say that Charley Pride wasn’t the first black country star or even the first black country superstar. His success is, however, specifically what Shelby Singleton would have been trying to replicate with Linda Martell.

You totally heard the word “colorblind” being censored in that Dee Mullins recording of “Irma Jackson.” I couldn’t find confirmation of this anywhere but I would be amazed if Shelby didn’t censor that himself to make the song sound even more controversial, playing into the hype that this was the big bad song Capitol Records wouldn’t let Merle Haggard do. And, yeah, it sounds a lot like they’re trying to fake a sitar sound in there with a banjo or something. I guess Shelby figured it was a counterculture song, hippies are counterculture, hippies seem to like sitar, what the hell, throw it in there. Again, if you want to say that a song like “The School Bus” means that Shelby Singleton, as a person, was a hardcore white supremacist, then you have to say that “Irma Jackson” means Shelby Singleton, as a person, was all about getting those races mixed together. It just doesn’t add up, especially when there’s a much better explanation staring us in the face, which is that controversy sells, gimmicks sell, anything that sells, that’s what Shelby Singleton wanted. For some of you, that’s no excuse – I get it – but stick around for the Doug and Rusty Kershaw episode of this podcast if you want to hear about a person in the music business who I think we have every reason to believe was a straight-up white power activist. They were out there and I don’t believe Shelby was one of them.

I can’t imagine anyone not knowing what a gopher is when I said that was Ray Steven’s first job in Nashville but that’s a person that you pay to hang around and go get whatever you need whenever you need it. If you need food, cigarettes, beer, they “gopher” it.

I did intentionally mispronounce “Arab” in the episode when discussing the Ray Stevens song. Pronouncing it correctly felt just as incorrect because that’s not how Ray says it in the song. Whatever.

I said that in 1972 Jimmy Ellis recorded a couple of Elvis covers. Obviously, Elvis did not write “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” What I meant was that Jimmy covered Elvis’ versions of those songs. Probably could have found a better way to say that but it wasn’t worth going back to fix.

I haven’t played a video game in years but I guess that Warren Smith song, “Uranium Rock,” was in Fallout 4. If that sounded familiar and it’s been driving you crazy where you could have heard it.

Some of you probably think it’s totally insane that anyone would ever believe Jimmy Ellis, a.k.a Orion, could possibly have been Elvis Presley. Well, remember that we’re talking about a world before the Internet. You couldn’t go to a magical little box and pull up 5,000 pictures in high enough resolution that you could zoom in to examine bone structure. As for the sound of his voice, I’ve read some pretty compelling arguments that the current quality of technology actually impacts the way we process information. So the better quality of recordings we hear and become used to, the better we get at hearing the things in those recordings. I would assume this translates to other senses because I’m in my early 30s and if I watch an action movie made in the last 5 years, any time there’s a fight sequence, I can’t tell what the hell is going on because of how fast the cuts are. This is apparently not a problem for younger people. All of which is to say, yeah, I think our eyes and our ears are better trained than those of previous generations and it’s really not surprising to me that people believed Orion was Elvis, especially once you consider how many of them just wanted it to be true for emotional reasons. You know, they didn’t want Elvis to be dead.

If you enjoyed this episode then the one book I would recommend to you more than any other is called Record Makers and Breakers: Voices of the Independent Rock ’n’ Roll Pioneers by John Broven. It’s over 600 pages of just stuff like this – old school music business hustlers, trying any and everything they can to get ahead from outside of the major label establishment. There’s a ton more about Shelby Singleton in there and you’ll learn a lot about so many other people just like him in the ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s.

How Nashville Became Music City, USA: 50 Years of Music Row by Michael Kosser is a good look at the world we’re entering with this three part series on Harper Valley PTA. When I say any hit song has many stories behind it, this is the kind of thing I’m talking about: the business of trying to get all the pieces put together in just the right way to come out the other end with a whole bunch of money. That’s Music Row.

There’s also Producing Country: The Inside Story of the Great Recordings by Michael Jarrett. This is a book that I almost don’t even want to tell you about because of how often I’ll be using it as a source but go ahead and read it, if you want to spoil half the episodes I’ll be making in the future.

Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock and Roll by Peter Guralnick. If you’ve read more than five books about southern music, Peter Guralnick probably wrote one of them. He knows what he’s talking about. This is the book for anyone interested in Sun Records, Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, rock and roll in general – must read.

You heard a lot more about rockabilly in this episode than any other so far. If those clips grabbed you and you want to know more, I would recommend Rockabilly: A Forty-Year Journey by Billy Poore.

The Starday Story: The House That Country Music Built by Nathan D. Gibson. Holy shit, what a book. I wish every little country label had a book like this written about it. Fantastic.

Country Soul: Making Music and Making Race in the American South by Charles L. Hughes is, as the title suggest, a look at race relations behind the scenes of the southern music business. I’d say it’s fairly objective, though some statements are factually untrue. Like, when the author writes that Plantation Records was started just to be an outlet for Jeannie C. Riley, completely untrue.

Country Boys and Redneck Women: New Essays in Gender and Country Music has an essay by Diane Pecknold on how Jeanne C. Riley and Linda Martell were treated by Plantation. I don’t always agree with her interpretation of the information but there’s a lot of good information here. For example, Diane writes about how Linda Martell’s time with Plantation came to an end. Linda’s husband was trying to take more control over Linda’s career and Shelby dropped her from the label. The author seems to think that has something to do with Shelby, as a white man, demanding absolute deference from his black artist and her husband. I don’t know how familiar this author is with the music business but, as I told you, Linda’s album was not a hit, which is the only thing Shelby ever cared about. Listen to next week’s Jeannie C. Riley episode to hear how her husband was also a problem for Shelby Singleton. And, if you think this is starting to look like sexism and Shelby exclusively felt the need to control female artists this way, watch that documentary on Orion.

And, of course, the David Allan Coe quote is from the collection of interviews by Alanna Nash titled Behind Closed Doors: Talking with the Legends of Country Music. Every person interviewed in that book will be featured in an episode of this podcast in some way. It’s essential reading.

Alright, that’s all.

Next week, Jeannie C. Riley. Let’s see how much trouble we can get in.

Shelby Singleton at the Rockabilly Hall of Fame Website

Shelby Singleton, Nashville Producer, Dies at 77 – New York Times