They call him The Storyteller because he distills life into words. Behind any story worth telling, you’ll always find another story. Maybe if we can get behind some of his best stories, we can reverse engineer the alchemy of Tom T. Hall. Maybe we’ll find the story about who he is and how he’s able to do what he can do with the English language…

Probably not but, worst case scenario, it will be an incredibly entertaining waste of time. Beginning with a condensed history of country music radio, we follow Tom T. from his early days as a young DJ into a seemingly effortless realization of his destiny to become one of country music’s greatest songwriters ever.

This episode is highly recommended for fans of songwriting, arguing about music, Net Neutrality, the music business, Bobby Bare, Dave Dudley, Jimmy C. Newman, Hank Cochran and songs for children.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

In addition to The Library, these books were used for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

What’s Hit?

For the past couple of weeks, I’ve been using “Harper Valley PTA” as the gateway into a conversation about hit country songs. Shelby Singleton showed us what a real promo person will do behind the scenes to make a hit happen. Jeannie C. Riley showed us plenty of the downsides to being used as the pretty face for a hit, how roughly the business can put you back down after it’s lifted you so high. The writer of “Harper Valley PTA” – Mr. Tom T. Hall – I think he can show us some things about how most fans experience hit country songs: country music radio.

One reason this podcast will never do an episode on someone who wasn’t impacting country music before the year 2000 is that it’s impossible to tell who won a war until after the war is over. Every generation of country music radio has been a war. Those of you old enough to be paying attention in the ’70s, ’80s, even the ’90s, know how much perspective on the genre is gained with the passing of time.

What is this “real country music”? Can anyone define what it sounds like?

I’m sure many of you remember in the ’90s, older country artists talked a lot of trash about what was being played on the radio. Waylon Jennings may never have really used that extremely vulgar simile to describe Garth Brooks’ music but he did say very critical things about Garth Brooks. Now, you go listen to the trash Luke Bryan puts out and tell me that doesn’t make Garth Brooks sound like Buck Owens.

Well, that’s not what a lot of fans of “real country” thought in the ’90s when Garth Brooks “ruined country radio.” Or, in the ’80s, when Urban Cowboy “ruined country radio.” Or, in the ’70s when Olivia Newton-John won a CMA award for Most Promising Female Vocalist of the Year and a bunch of traditional country acts, like Porter Wagoner and Conway Twitty, all got together at George Jones’ and Tammy Wynette’s house to form the Association of Country Entertainers to protest smooth pop “ruining country radio.” But, in the ’60s, the Nashville Sound had already “ruined country radio.” And that started in the ’50s because Elvis Presley “ruined country radio.” When drums started showing up on more country records in the ’40s, well, it flat out “ruined country radio.” And that only happened because in the 1930s people like Bob Wills couldn’t settle the hell down and play some nice, pure country music, like Jimmie Rodgers or The Carter Family.

I’m not sure there’s ever been a time that country radio wasn’t hated by the fans of the previous generations’ country music. Ask a fan from any point in history to define the sound of country music and they’re likely to say something along the lines of, ”Well, it’s sure not what they’re playing on the radio these days!”

The Saddest Songs You Ever Heard on Your Radio

I see a few things happening, here.

One, country music is a traditional genre. You can easily trace its sonic roots and performative function at least back to the troubadour ballads of the Middle Ages in Europe. At every phase of its evolution between then and now, there’s been a tug-of-war with tradition holding one end of the rope and creativity holding the other. This is art. Artists want to explore their medium and they are inherently influenced by the world around them, which is different for every artist and changes every day.

The progression of technology speeds up this entire process. For a lot of people, the devolution of country music goes hand-in-hand with musicians and producers being able to create sounds they’ve never heard before. Give a kid a toy and they’re going to play with it. If the kid makes country music, it’s guaranteed to piss off some people listening to their radio. This is why there’s always been some movement of relative outsiders keeping alive the “real country” from the sidelines – Neo-Traditionalists in the ’80s and ’90s, so-called Outlaws in the ’70s and ’80s, the Bakersfield Sound of the ’50s and ’60s. Some of these people did have commercial success but some of the greatest country music ever was made by people you’ve never heard on the radio; people who built underground followings, often through constant touring, often staying on the road until age or illness physically prevented them from going on. That being said, talking about commercial success (or the lack thereof) is essentially the only way we can discuss this past with objectivity. Everything else is just me telling you what I do and don’t like or you telling me the same thing. Comparing record sales and radio hits, though by no means a pristine data point, is the closest thing we have to a measuring tool for this music.

Now, another problem with country radio is a problem with all of radio. The story of music radio from its beginning until now is a story of homogenization. Decades ago, we were able to turn a knob and find a DJ who’d earned our trust by being the first person to play our favorite songs when nobody else was playing them. That DJ would say, “Hey, listen up! Here’s the new thing.” And we would listen. If you want to read about why that doesn’t happen on big radio stations anymore, go read about the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Those bastards deregulated how many radio stations could be owned by the same corporate entity and, all of the sudden, your playlists started being handed down from HQ. The radio stations, the publicists, the record labels – now, it’s all just a big machine. Tom Petty made an entire album about this, called The Last DJ, in 2002. I promise you, things have not improved. Clear Channel banned the title track for being “anti-radio,” even though it sounds pretty pro-radio, to me – or, at least, what radio should be. This is another reason why it’s only worth talking about what singles were radio hits up to a certain point. Because, after that point, they’re basically just letting us know what they’ve decided the new hits will be.

This brings us back to technology.

“We don’t need real DJs on the radio anymore because, now, they’re on the Internet and we call them curators and tastemakers.”

“The Internet gives everyone an equal chance to be heard.”

It sure does. But almost nobody is listening. There’s an unprecedented amount of noise competing for our attention online. How many of us are really digging any deeper than what gets put in front of our faces? Hey, maybe you are but you’re very much the exception. It’s easy to assume everyone else is doing what we’re doing, listening to podcasts on our smartphones, checking that indie reviewer’s Twitter account to see what’s good or listening to curated playlists to support baby bands. Most people who listen to music are not doing these things. According to the latest Nielsen Research data I could find, from August of 2017, over 80% of US consumers age 12 and older and 9 out of 10 teens are still listening to radio. 87.9% of Americans aged 12 to 17 listen to 10 hours of radio a week. 75% of adults listen to radio in their car. If that big machine decides kazoos are the next trend in country music, guess what’s happening next year? It’ll be you and me complaining and kazoo country blaring out of every college party. The Internet can’t stop it. I’m not saying this is anything new but, now, the machine is bigger than ever and it’s getting away with all the things it always wanted to do.

Now, to bring it all back home, why does this have to result in country music that isn’t country music at all? Why can’t they do everything they’re doing with “real country music,” that’s good? One word: money. Pop music, by definition, outsells country music. When country music does pop sales figures, you’ll see that country music on the pop charts. What possible reason would the big machine have for not wanting to be there. Tradition? Artistic integrity? Get real. Go the opposite direction. When country music comes nowhere near pop sales figures, the country artist who made it is in danger of losing their record deal. Like how Columbia Records dropped Johnny Cash in 1986. (That happened.)

Okay, so, you’ve got A&R people and you’ve got in-house producers working at these record labels, right? These are the people responsible for bringing these artists to the label in the first place and they’re influencing what kind of music they make. They want to look like they’re good at their jobs by working with bands who move units and make money. Look at the list of people who always get the credit (or the blame) for the Nashville Sound, that first great banishment of country music sounds from country music radio. It was all producers and suits at the label – Owen Bradley, Bob Ferguson, Steve Sholes. The only one who’d ever really been on the other side of a record deal, Chet Atkins, was very much acting as a producer here. The Nashville Sound wasn’t an organic evolution of country music from artists exploring their creativity. It was another form of homogenization, a calculated effort to de-countrify country and sell it to pop audiences to stay competitive. Artists who didn’t play ball were left to rot while promotional resources were thrown behind whatever new pop/country hybrid represented the labels’ most recent swing for the crossover fences. It’s been happening ever since and it will never, ever stop.

Jim Reeves & Chet Atkins

Meanwhile, we’re still left with the same problem we started with. How do you define country music? Like most people, I like to think I know it when I hear it. Or, maybe it would be more accurate to say I like to think I know it when I don’t hear it.

The Person Comes First

Tom T. Hall – a man who broke into the music business by working as a real DJ, a man who, to say he had a way with words would be an understatement – when he got around to answering the question “what is country?” he didn’t say one word about the way it sounds…

Odds are you’ve got a favorite song by Tom T. Hall, even if you don’t know it, and it’s a safe bet that it isn’t “Harper Valley PTA.” George Jones called Tom T. Hall “truly one of the greatest country songwriters of all time.” Tom T. Hall’s writing has such a distinct voice that, to this day in Nashville, other writers will refer to their own work as a Tom T. Hall-type song. There are not very many names we use that way.

One word often used to describe Tom’s writing is “literary.” Similar to Bobbie Gentry’s best work, there’s a quality to Tom’s narratives reminiscent of the great American short story writers in the 20th century. Sinclair Lewis, Flannery O’Connor, Ernest Hemingway – these are Tom’s influences. His nickname is The Storyteller. It fits. Ask him what one of his songs is about and more often than not he’ll tell you a story about something he saw or did or something he heard someone talking about somewhere. The story that ends up in his song almost always starts with a story outside his song. Naturally, this is something plenty of people attempt to do but it’s possible nobody does it as well as Tom T. Hall. Like the greatest at anything, he even manages to make it look easy.

Perhaps even more notable in Nashville than his talent is the fact that Tom T. Hall seems to have always been a genuinely good person. There isn’t anyone with many negative things to say about him.

Unlike the other two major characters responsible for “Harper Valley PTA,” he’s a Kentucky boy, born in 1936, the fifth out of eight Hall children. (His poor mother.) Eastern Kentucky’s never been a place of wealth and it certainly wasn’t in the early ’40s. His father worked in brick factories and, later, became a reverend.

One of Tom’s earliest memories, from around the age of four, is of his mom waking him up in the middle of the night to listen to Ernest Tubb on the radio. According to Tom, he’s been working on music since 1940, joking, “I started playing the guitar when I was four years old and I’m just as good today as I was then.” But, seriously, the family moved into a new house when Tom was five or six years old. The previous occupants had left a guitar behind – nothing special but, with a little work, playable. His father fixed it up and that was Tom’s first guitar. If there was something else Tom was meant to do with his life, nobody ever got the chance to find out.

Oh, sure, he had odd jobs. And I do mean “odd.” At the age of 12 or 13, Tom had a summer job mowing grass in a graveyard. A couple of years later, he was working in a hundred degree clothing factory. Then, a funeral home. And, later, as a salesman. Tom had dropped out of school in his early teens and none of those jobs were a passion. They were just ways to put money in his pocket and have a distraction to keep him from getting in the way of whatever song was currently being written in his head.

He says his first song came at the age of nine, after hearing an argument between the young, married couple next door. The husband asked the wife, “Haven’t I been good to you?!” That sounded like a country song to Tom, so he made one up. His first band came within a few years of that. The Kentucky Travelers were just a group of kids who liked bluegrass enough to want to play some but they managed to get an audition at a local radio station…

It’s funny how similar podcasts are to old school radio in a lot of ways. If you listen to a lot of podcasts then you’ve heard at least one where the host reads advertisements themselves instead of just playing a commercial from their sponsor. Well, that’s how radio used to work back in the day. And, if the radio segment you were listening to was hosted by a band, then they may even just write a song for their sponsor and perform that. Probably the most famous example of this is Pat Twitty’s jingle for Martha White Self-Rising Flour, performed about a bajillion times on the radio by Flat and Scruggs. So, when the Kentucky Travelers got their radio job it was with a station sponsored by Polar Bear Flour. Little Tom assumed he was supposed to write them a jingle, so he did and they just loved it. That’s the secret to a long career in radio, people – keep the sponsors happy.

The Kentucky Travelers held that gig until the Korean War broke out and took some of the older boys away from the group. The radio station kept Tom on, which is how he got that first job as a DJ. This was in 1950, making him 14 years old. That’s very young to be a DJ but he must have been good. They kept him on the air until he left for the army, himself, in ’57 or ’58.

Before leaving, he pulled a funny little publicity stunt in the name of charity. There was a March of Dimes fundraiser and Tom had the bright idea to get locked up in the local jail until they raised $500. Well, maybe the town took the name of the charity too literally because the average donation came in the form of coins and Tom had to broadcast from jail for a full week before raising that $500.

According to Tom, he joined the army while bored on his lunch break one day. He just happened to wander into a recruiting center. According to his boss at the station, Tom went on a bender for three days, came into work drunk and got fired. Tom says his old boss made that up after he told him he quit because the boss needed an explanation for why Tom was so suddenly gone. Either way, Tom did four years in the army, mostly stationed in Germany. He used the time, wisely, to finish a high school-level education and even pick up some college credits. They put him on the Armed Forces Radio Network over there, so his broadcast skills stayed fresh and he had a band going, too. When he got some leave, he’d hop over to another country for a while, see a little bit more of the world.

Little Commercials for Life

Spring of 1961. Back in the US, Tom tries to get a band going with one of the original Kentucky Travelers but it doesn’t really work out. He ends up back on the radio mic, moving from station to station, wherever the pay is better. Mostly, that means West Virginia.

It’s probably worth noting that most of these gigs require Tom to write his own copy for the commercials he reads on-air. These are not songs, just tiny little scripts to read – again, like you hear in a lot of podcasts these days. But being forced to churn out disposable content like that can really make a writer out of someone. (If it seems funny that writing commercials could make you a better songwriter, well, try thinking about songs as little commercials for life.)

So, he’s in West Virginia. It’s the radio job in the day; nights back in the room where he lives, above a library, to fill his head with writers, like William Faulkner, Sinclair Lewis, Ernest Hemingway, Mark Twain, until he gets tired and goes to bed. Get back up the next day and do it all over again, every day except Sunday. On Sunday, Tom goes over to the Moose Lodge to play poker and get drunk. And, like every other artist we’ll talk about who worked on the radio, here and there, Tom books live appearances and promotes them on-air.

Hanging out with everyone after a show one night, playing songs for each other, a guy from a publishing company in Nashville hears some Tom T. Hall songs and takes them back to his bosses to see what they think. His bosses are Jimmy Key, Jimmy C. Newman and Dave Dudley at Newkeys Music. In October of 1963, Jimmy C. Newman’s new single, “DJ for a Day,” comes out on Decca. The writer on the label is listed as Tom Hall. You can already see how Tom draws from his own life experiences, right from the beginning.

When “DJ for a Day” goes Top Ten for Jimmy C. Newman, Newkeys Music tries to talk their new hit writer in to moving to Nashville. Tom knows for certain that he wants to be a writer but he’s not so sure about this songwriter business. He goes to Salem, Virginia, instead. There’s another radio job there – one that doesn’t require him to write ad copy or do anything else besides be a DJ, leaving time for him to take college courses in formal writing, as applied to fiction and journalism. Of course, he kept sending songs to Nashville, they kept getting cut and, the thing about this songwriter business is, when those checks start showing up for doing nothing but writing down some words to a melody, it gets a lot harder to walk away.

Even after making the decision to move to Nashville and really be a songwriter, Tom wants the date to be “auspicious,” so he waits until New Year’s Eve to leave, arriving on January 1st, 1964. Other sources have this move taking place after Dave Dudley’s recording of “Mad” became another early Top Ten hit for Tom. (Side note: that single was on Mercury records, co-produced by Shelby Singleton and Jerry Kennedy. It didn’t come out until August of ’64.) Though, there’s no reason it would be important what month in 1964 Tom T. Hall moved to Nashville. What matters is there isn’t a radio job waiting for him this time. Newkeys Music pays him $50 a week, so he can survive long enough to write songs and bring in enough royalties to pay back all those $50 a week loans. This is called being on a draw.

His royalty checks do keep getting bigger but a songwriter life in Nashville is way more expensive than a bookworm life in Salem, VA. This is when Tom becomes a song plugger. We haven’t talked about this yet, either, so here’s what a song plugger used to be. The entire record industry was built on songs, obviously. But there’s no telling how many dozens of songwriters showed up to Nashville every single day with dreams of getting their songs recorded. Record labels, producers, artists who’d already made it – these people could literally open the front door of any bar downtown and yell, “Anybody got any songs to record?!” and probably cause a bar fight from every writer rushing to get there first. Some of those writers may even be good. Most of them would not have been. What you need is a bit of quality control. You need someone who’s already listened to all the new songs in town and pulled out the good ones to show you when you come calling, like how the bartender at your regular spot knows your drink and starts making it as soon as you walk in. That’s a publishing company and the actual person you’d be talking to is a song plugger. You could go to their office, if you want. More often than not, the song plugger would come to you – at the record company’s office, the artist’s home or hotel room, even straight to the recording studio in cases of emergency – always with a box full of tapes and lyric sheets.

In his book, The Storyteller’s Nashville, Tom tells a story about a difficult song plugging session for Rex Allen. By the time Tom arrives, there are empty bottles and reels of tape all over the hotel room. This one’s been going on for a while. Rex isn’t hearing anything he likes or, maybe more accurately, isn’t seeing any names of songwriters he recognizes on the lyric sheets. He keeps saying he wants a hit. He keeps asking, where’s the stuff from the hit songwriters. Tom waits with the other pluggers, watching Rex lay on his bed in a bathrobe, listening to him complain. Then, it’s Tom’s turn. He hands Rex the lyric sheet of each new song, hits play on the tape, repeating the process every time Rex interrupts the song to say “next.” Four songs into this, Rex starts in on another long tirade about needing a hit, so Tom just packs up his stuff and leaves. This was probably pretty typical of a hotel room song plugging session.

Thankfully, Tom didn’t have to be a song plugger for very long. I would never accuse him of pushing his own songs to the top of the pile in those sessions. But he did keep getting his stuff recorded by his bosses, Dave Dudley and Jimmy C. Newman, as well as artists, like Flat & Scruggs, Billy Grammer, Nancy Sinatra (with Lee Hazlewood), Jean Shepard and Johnnie Wright. Johnnie took Tom’s song “Hello Vietnam” to #1 in 1965. You may have heard that one a couple of decades later at the beginning of Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket.

Two things happened around the time “Hello Vietnam” went #1. Tom had a song on the b-side of The Statler Brothers’ monster hit, “Flowers on the Wall.” That b-side was called “Billy Christian” and nobody talks about it much anymore but “Flowers on the Wall” was a Top 5 hit on the pop charts. Everyone who bought the front of the record bought the back of it, too. Those b-side royalty checks cash just as good as the a-side checks. The other thing that happened in 1965 is, Tom began working on a song that would become “Harper Valley PTA” when he finished it in 1967.

Probably some time in 1966, Jimmy Key started trying to convince Tom he should record an album of his own songs. Just like Jimmy had a hard time getting him to move to Nashville, he had a hard time getting him to record an album. It took about a year and Jerry Kennedy finally getting in his other ear about it for Tom to get on board with the idea. Jerry told him that, while amazing, his songs were often too personal to Tom’s own life experiences for other artists to want to record them. In July of 1967, the first Tom T. Hall single came out on Mercury Records. They added that “T.” to give his name a little more character and, hey, maybe it worked because “I Washed My Face in the Morning Dew” went to #30.

The standard line on Tom T. Hall as a singer is that he sure is a good songwriter. He’s no George Jones but he’s certainly no worse of a singer than, say, Johnny Cash. Some might say every Tom T. Hall record sounds the same because his voice always sounds the same. I would counter that Tom T. Hall writes very memorable melodies and there has never been a time when a song was playing and you weren’t sure whether or not it was Tom T. Hall singing. His voice stands out. It’s recognizable and, by the fifth time you hear it, you probably know the words.

I Want to Tell You All the Story

If you pick up all the pieces from various versions of how Tom came to write “Harper Valley PTA,” it comes together something like this. The inspiration for Tom to begin writing the song, like always, is in his own past. Tom writes, “When I was a small boy, in the town where I grew up, there was a lady who used to have parties on Saturday nights. Obviously I changed her name in the song. She would have people over and they would have drinks and talk and listen to records. It wasn’t a crack house or anything wild like that. They were all pretty respectable people and she had a daughter. This is all in the song.” That’s the memory Tom carried around his whole life and where he started with the song.

Skip ahead to 1967. A radio station outside Nashville is hosting a “listener appreciation day” party. Tom’s there and so is Margie Singleton with her new husband, Leon Ashley, as in Ashley Records. Margie’s talking to Tom and she tells him he ought to write her a song like Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billie Joe.” On his way home from the party, Tom drives by a sign that reads “Harpeth Valley Utility District.” He changes “Harpeth” to “Harper” and finishes that idea he’d started a couple years back. He makes an acoustic demo for Margie but she’s out on tour. Tom files the song with Newkeys Music and it gets to Billy Grammer. Grammer takes it home but brings it back, saying his kids don’t like it but he’ll record it if he can change it around some. Tom’s not into that and I still wonder if Billy Grammer ever forgave his children…

While that was going on, Margie Singleton’s husband, Leon Ashley, cut a demo of the song with Alice Joy. This is the demo that sits in Shelby Singleton’s desk for months, while he waits for a Jeannie C. Riley to come along. [This is where I’ll remind any Tom T. Hall fans checking out this podcast for the first time, I don’t do much recapping. You’re missing a lot if you skipped the previous two episodes on “Harper Valley PTA.”]

According to legend, the Friday night of the “Harper Valley PTA” recording session, Tom’s drinking at Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge. It’s possible he’s working. Many years later, he said there was a time when he could write a song and carry on a conversation at the same time. He’d sit, drink a beer and talk to people in Tootsie’s while working on a song in his head. Anyway, someone stops by the bar, tells Tom his song is being recorded and it sounds like a hit. Tom runs down the street to the studio. He’s supposed to have gotten there in time to hear the second take. If that’s true, he hears a small change to his lyrics.

The way he’d written the final line in the song was “that’s the day my mama put down the Harper Valley PTA.” Shelby Singleton’s second wife, Barbara, is in the studio that night. After the first take, she suggests changing the line to “the day my mama socked it to the Harper Valley PTA.” (“Sock it to me” was the hip new catch phrase, thanks to Laugh-In.) Jeannie sings the new line and all the things I already told you about happen.

Speaking on the immediate popularity of the song, Tom T. Hall once said it was like finding $100,000 while walking down the street. Since he was the guy who wrote the hit, they hit him up for a few more songs on the Harper Valley PTA full-length. None of those songs were hits but that’s a bigger royalty check with every sale of the LP. Tom once met a guy in West Virginia who bought a copy of the album, even though he didn’t own a record player and had no way to listen to it. That’s how you know a song has become bigger than itself. That’s hype.

In later years, Tom would always maintain that he never felt interested in trying to duplicate “Harper Valley PTA.” It’s quite likely that is true. But, if it is true, then I’ve got another Shelby Singleton story for you. In 1968, Dee Mullins, Shelby Singleton’s go-to guy for trying to piggyback off a hit or a headline, releases the single, “The Continuing Story of Harper Valley PTA.” Sole writer, Tom. T. Hall. Or, at least, that’s what you’d believe, if you only saw the label of the single that was released to the public. Look up the copyright info on the song or find a picture of the label for the radio promo 7” and you’ll see two other writers listed, Clark Bentley and Jerri Clark. Considering that “The Continuing Story” is written so poorly that it isn’t even funny, I suspect those writers were brought in to milk every last cent out of this cash cow. Since Tom would have to be listed any way for writing the original, it seems they decided to just make it look like he wrote the second one all by himself, too.

But Tom T. Hall had surely moved on to better things.

His first Top Five single, as an artist, came out within a month of “Harper Valley PTA” leaving the #1 position on the country charts. You can hear Jerry Kennedy’s dobro on the track, too. “Ballad of 40 Dollars” was inspired by that first summer job mowing grass in the graveyard. He talked about it at a Country Music Hall of Fame event, “Of course, when they had a funeral I had to shut down the mower… That song is about my experiences shutting down the mower and watching the funerals. The irony is, when somebody else dies, I don’t know how it got to be this way, but the rest of the world more or less forgives their sins. They say ‘Oh he was a wonderful guy, a good person’ which is one of the ironies of philosophy, I think.” That became the title track of Tom’s first album, released in 1969, which opens with his own excellent recording of the song Bobby Bare would hit with in 1970, “That’s How I Got to Memphis.”

With plenty of supply to meet the new level of demand, Tom actually put out two albums in 1969, both produced by Jerry Kennedy, who once said, “I used to get all fired up when Tom would call and say ‘Hey I got a batch of new things I’d like to play for you.’ It was like opening things at Christmas. I knew out of that batch there were gonna be some killers; there always were. It was just like watching a movie when I’d hear these things – you could actually see the story unfolding.”

The killers are packed into his second album, Homecoming. There’s “Margie’s at the Lincoln Park Inn,” which had already been a hit for Bobby Bare. Then, Tom’s first #1 with his own song, “A Week in a Country Jail.” That one isn’t about the week Tom spent in jail for charity. Just like it says in the song, it’s about a different time, when he was arrested for speeding. Only, he had the bad luck to be arrested just as the judge had to leave town for a funeral, so it took close to a week for him to be released.

Now, we’ve been talking about some major songs in this episode already and it’s easy to lose perspective on how big of a deal each of these achievements is on its own. Put it this way, three singles from Tom T. Hall’s second album were Top Tens: “A Week in a Country Jail,” “Shoeshine Man” and, the miniature masterclass in breaking every rule of writing a hit song, “Homecoming.” There’s no chorus. The word “homecoming” isn’t even in the song. We could spend hours just talking about Tom T. Hall songs but let’s talk about his life for a second.

Like a Fox on the Run

If fame and fortune ever really does change people, it doesn’t seem to have changed Tom at all, besides giving his eccentric tendencies a little more room to breathe. Before he was rich, Tom started his days with coffee and writing, believing the best stuff came when he was fresh from sleeping. After he got rich, Tom started his days with coffee and writing. The only thing that changed is where he was doing the writing.

In 1969, Tom put a dent in his bank account by purchasing Fox Hollow, 60 acres of farm land, half an hour outside of Nashville, where he moved with his wife, Dixie. Long, white fences; big, plantation-style home; a lake on the property – the whole thing was like a dream come true.

Dixie Hall was a songwriter herself and she’ll definitely pop up in some other episodes. She lived with Mother Maybelle Carter for a while in the early ’60s. You know, when Johnny Cash was trying his damnedest to marry into the first family of country music? But those are different stories.

Dixie & Tom T. Hall at a BMI event

Tom and Dixie met at the BMI awards one year because they were the writers of opposite sides on a hit Dave Dudley record from 1965. Dixie and Ray King wrote the a-side, “Truck Drivin Son of a Gun,” and Tom wrote the b-side, “I Got Lost.” Seated at the same table for the dinner part of the evening, Tom asked Dixie if she liked potatoes. When she said she did, he followed up with, “Is that how you got fat?” Since she was clearly a slim woman, this was plainly meant as a joke and Dixie either thought it was funny or felt sorry for the idiot because they eventually got married, in March of 1968, just before “Harper Valley PTA” took over the world. The relationship seems to have organized itself pretty quickly. Dixie – the grownup, handling business and finances.

Tom? Same old Tom. Mild-mannered but up for a good time. Responsible, until an opportunity to have a good story presents itself. Like the one from the late ’60s that George Jones tells in his autobiography.

It’s one of Tom’s early road gigs in Texas. George Jones, Willie Nelson and Wynn Stewart, with Tom making $750 to open the show. Well, out of that $750, Tom had to pay for the tour bus they rented and pay for his band’s food and hotel rooms, so he was barely making any money on the deal at all, especially after losing at poker to George and Wynn. Tom had to go wake up his manager in the middle of the night to settle with the guys. I’m sure he’d do it again the exact same way, just to have the story of losing at poker to George Jones and Wynn Stewart. And, anyway, I guess George figured it was even after he cut some of Tom’s songs, later on down the road.

Tom’s brand of drunken mischief never seems to take the dark, depressing turn we almost always have to take when talking about country musicians who drink. It’s quite the opposite. One time, Hank Cochran got drunk and passed out at a Fox Hollow party. Tom eventually got tired, himself, but he didn’t want to go to bed because he was worried that Hank would wake up and try to drive himself home while still drunk. So, the solution Tom found was to roll Hank up in the rug he’d passed out on (presumably, with Hank’s head sticking out, so he could breathe) and, then, lay the rolled-up rug on top of a pool table, so Hank wouldn’t be able to get out even if he did wake up before everyone else.

Of the three main actors who created “Harper Valley PTA,” there’s no question that Tom T. Hall came out the other side in the best shape. He got the money and didn’t blow it. He respected the person he married and got to share most of his life with a loving partner. He gained the respect of industry peers and audiences, which he’s maintained for over 40 years. It would have been so easy for him to start phoning it in at any point past the ’60s, yet the quality of his work never diminished. If you were ever a Tom T. Hall fan, it’s safe to say you’ll always be one because all he’s ever done is be great at being Tom T. Hall. Bob Dylan has taken a shot or two at Tom but you can choose what you think is the worst Tom T. Hall album and I’ll choose what I think is the worst Bob Dylan album and we can sit down and compare those any day you want to do that.

In the 1970s, as an artist, Tom put 16 of his own songs in the Top 10. Six of those went to number one. Here’s another way to look at it: of the 30 Tom T. Hall singles released from 1970 to 1979, only 4 failed to hit the country Top 20 and all 4 of those were in the Top 40. He literally released nothing, as an artist, but hit singles for a decade. Not bad for a songwriter. And, of course, that’s not even mentioning the many hits other artists had with these songs. But let’s stay focused on Tom.

His first #1 of the ’70s was “The Year That Clayton Delaney Died.” Clayton Delaney was just a name that Tom made up for a real musician in his hometown named Lonnie Easterly. When Tom says his songs are based on true stories, he’s not always talking about only his life. These aren’t audio documentaries. He starts with something that happened to him but, by the time it’s done, there’s usually more there than even he may realize. Like with “Old Dogs, Children and Watermelon Wine,” his next #1 hit, in 1972. Reading the lyrics of the song, it seems like straight autobiography and it’s quite possible Tom even believed that’s what he was doing when he wrote the words down. There’s something hidden in there, though, and according to Tom it even took him two years to see it himself.

A thing maybe worth knowing about the conversation in the song is that it happened the night Tom played a concert with George Jones and Tammy Wynette across the street from the 1972 Democratic National Convention in Miami…

Being the guy who wrote “Harper Valley PTA,” you may expect Tom T. Hall to be pretty outspoken in his politics or, at least, out there, pointing fingers in his songs. He did a little bit of that but not very much. There’s a killer song from 1970, on his fourth album, I Witness Life. The song is called “America the Ugly” but it’s not nearly as inflammatory as you would expect from that title. The song talks about homeless drunks, hungry children, able-bodied men unable to find a job, all of that – ending on a call for us to figure it out with the line “if we get heads and hearts together, we won’t have to hear them say America the Ugly today.” It’s vague enough that both liberals and conservatives (and everyone in between) could think it’s written by one of them. Add that to “The Man Who Hated Freckles” or “I Want to See the Parade,” both about the ignorance of racism, and that’s about as political as Tom ever got on his albums. Though, he did, later, consider running for governor, presumably as a Democrat.

So, after the infamous 1968 DNC in Chicago turned into a bloody riot, there were some concerns about the 1972 DNC. The political arena hadn’t calmed down much and people like Hunter S. Thompson were worried they could be in for a “week-long orgy of sex, violence and treachery” at the 1972 DNC in Miami. Activist Jerry Rubin went on television to promise 10,000 naked hippies would descend on the convention for non-violent protests. Somewhere in there, someone thought it would be a good idea to have some country music happening in Flamingo Park, across the street. Back to Tom, “This was just across the street from the convention center, so these young people became more interested in the music than in the politics. They all came over and brought a case of beer and fired up a joint and sat around in the grass. And we played music for them. They left the convention alone.”

After that show, Tom went into the hotel bar for a whiskey or two before bed and was told by an old housekeeper that the only three things in this world worth a solitary dime are “old dogs and children and watermelon wine.”

Tom, in a later interview, “The classic bartender was standing, wiping a glass, and I don’t know why they do that but he had this one glass and he was wearin’ it out wiping it. And watching ‘Ironside’ on TV. I figured out later that the old man in the song was retired. He said ‘I turned 65, by the way, a few months ago.’ What he was telling me was he didn’t need this job. He was on Social Security. You know, I’d written this song and it took me two years to figure out what that line was about.”

In other words, there’s a fourth thing in this world “worth a solitary dime” and that’s finding a way to make yourself useful. But you don’t need to know the specific age of retirement to pick that up from “Old Dogs, Children and Watermelon Wine.” Part of what makes Tom T. Hall one of our best songwriters is that he knew there was something worth keeping in that line, even if he didn’t know what it was until later on down the road.

There was a 10am session booked in Nashville the following morning, so he had to get up early to catch a plane. Tom wrote “Old Dogs, Children and Watermelon Wine” on a vomit bag during the flight. His producer, Jerry Kennedy, who was waiting on him at the studio, said, “His plane was late gettin’ there and he walked in with that song written. He didn’t even have a melody finished for it. All of that was finished right on the date, and to me, that’s one of the best songs he’s ever written.”

Just Like Tom T. Hall’s Blues

1973 and 1974 are the best years for Tom T. Hall, as an artist, if you’re going by radio and record sales. He had a four-single run of hits, three number ones and a number two, starting with “I Love” in 1973. This is the particular song Bob Dylan was talking about when he criticized Tom T. Hall in his MusicCares Person of the Year acceptance speech, calling it “the little baby duck song.” It is a simple song. It’s also his biggest hit as a singer. This thing crossed over to the pop charts and went to #12. Whether or not you love it, a lot of people did.

Tom may have been giving a nod to critics of “I Love” with his next single, a hit song about hit songs, “That Song Is Driving Me Crazy.” Then, back to that list format for “Country Is” and “I Care.”

Many songwriters go through a phase of writing list songs. (Bob Dylan did, too, in case he’s forgotten “Gotta Serve Somebody” or “Man Gave Names to All the Animals.”) A list song is exactly what it sounds like: pick a theme, make a list, sing the list. “I Love” was a list of things Tom loves. “Country Is” was a list of, you guessed it, what country is. Tom tells us that country is all about having the good times, listening to music, singing your part, walking in the moonlight, etc. It came out at a time when everyone was in the middle of yet another debate over what was and wasn’t country music, who should and shouldn’t be considered a country artist. Then you’ve got “I Care,” the only single released from Tom’s album for children, Songs of Fox Hollow. It’s a list of circumstances when Tom T. Hall wants you to remember that he cares about you.

So, yeah, these list songs may be seen as a departure from The Storyteller’s trademark style but these were some of his biggest hits. People responded to them. These simple words express complex feelings and you could say that about the entire genre of country music. Those of us capable of expressing these feelings ourselves may not resonate with it but not everyone who cares about another person has such an easy time communicating that. Some of us have a roadblock between the feeling and the words. Having “I Care” by Tom T. Hall on a record we can give to another person, that means something.

Anyway, some people say Tom wasn’t cut out to be as famous as his list songs made him. In 1973, at the very first Willie Nelson 4th of July Picnic in Dripping Springs, Texas, Tom broke a string on his acoustic guitar. Not a big deal, except, instead of handing it off to a stage hand to change the string, Tom threw the guitar into the audience, which started one of several fistfights that day. It could have seemed like a funny thing to do at the time, you know? Only, this isn’t an isolated incident…

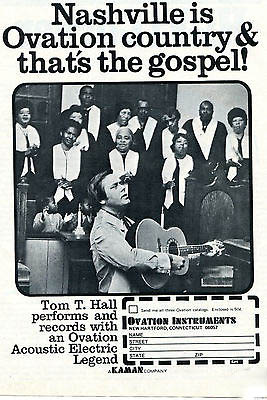

At this time, he had an endorsement from Ovation guitars and they actually had to have a talk with Tom because they didn’t see how it was possible for him to go through two guitars a week. Apparently, any time something would go wrong in his show, he’d smash his guitar onstage and throw it out to the crowd. Of all the people famous for smashing their instruments on stage, Tom T. Hall must be least likely of the bunch. Although, it could be naive to believe anger was the motivating factor, here. Go back to the Louvin Brothers episode. Ask yourself if Ira Louvin would have stopped smashing his mandolins should some company giving them to him for free ask him to stop? Of course not. Ira smashed his instrument because he couldn’t control his rage. Tom did it for show. This is a man who rarely seems to lose sight of the perspective that he’s living his own personal dream. When he really was displeased with something, his typical reaction was to simply walk away.

He joined the Grand Ole Opry in 1971, while it was still at the Ryman Auditorium, in downtown Nashville, where it had been since 1943. In 1974, the program moved out to the new Opry House, where it is now at the Opry Mills Mall but what was then a country music themed amusement park, called Opryland USA, like a Six Flags-type of thing. Tom resigned from the Grand Ole Opry. Six months later, he gave a reporter the explanation that the new venue just didn’t have the same thing going for it as The Ryman, “As soon as we moved to the new place, I immediately and instinctively did not like it. The Ryman was different. It was almost an ego trip, really, standing on the same stage where Hank Williams once performed and knowing there were people out there who appreciated what you were doing, who had driven in some cases a couple hundred miles to see it. But the audiences now don’t know what they’re looking at. The old time acts are being put down and dismissed. They’re playing to people who don’t know what they are seeing, who stop in at Opryland on their way to Florida and take in a performance of the Opry and think, “What the hell is this guy doing?”

Without getting all the way into it right now, Tom T. Hall was definitely not the only country artist who had this opinion. But that may not have been his only reason for quitting the Opry. In the six months between his disappearance from the Grand Ole Opry lineup and his giving an explanation to the public, the press had themselves a grand ole time stoking a fire under the rumor that Tom had quit due to uptight rules not allowing him to use banned instruments onstage, namely a horn section. Now, it’s a fact that horns were not allowed on the Opry stage and his most recent hit, “That Song Is Driving Me Crazy,” featured a full Dixieland jazz band arrangement with heavy use of horns. Tom, from then until now, has consistently downplayed this as a reason he left. His resignation was communicated through a private and respectful letter with Opry personnel. Tom didn’t smash anything or rush to the media in a fit of anger. This just happened to be a time when Tom was at the height of his popularity and only six months after the Opry faced a different controversy over Skeeter Davis…

Around Christmas of 1973, she saw some “Jesus people” being arrested on her way into The Ryman. She went onstage, made a statement about how much it burdens her heart to see police arresting people just for saying “Jesus loves you” and, then, she sang “Amazing Grace.” Religion is welcome on the Opry stage. Criticizing police is not. Skeeter was suspended from the Opry that night. This sort of thing sells a lot of newspapers. Following that, anything that looked like a scandal at the Opry, the media wasn’t gonna let go. They kept calling all Tom’s people, trying to get an explanation for his absence, until, finally, his booking agent’s son yelled something about them not letting Tom have his horn players and slammed the phone down. Many people, to this day, believe that’s the only reason Tom quit the Opry. Not that it would make him irrational or hot-headed – others have quit the Opry for less – but, according to Tom, it’s just not the truth.

In 1975, those horns were back in Tom T. Hall’s final #1 as an artist, “Faster Horses.” It goes back to that “Old Dogs, Children and Watermelon Wine” template. Tom puts a version of himself into a conversation with an old cowboy version of – well, actually, it’s another version of himself. Tom was walking around New York City with a country boy friend of his. The friend made a comment about it being a tough place. Tom replied, yeah, New York City is all about faster horses, younger women, older whiskey and more money. Of course, that wouldn’t have been as good as it coming from an old cowboy, so that’s whose mouth Tom put the words in for another hit. He kept hitting the Top Ten into the ’80s, so it’s not like this is his swan song or anything, but if we’re sticking to the number ones, which is probably the exact wrong way to go about listening to Tom T. Hall, the trail ends here.

If you can’t tell from reading, it is my belief that you should absolutely go buy this man’s albums. As always, there are links in the Liner Notes at the bottom of this post. Start at the beginning and work your way forward. Take your time with each album. There’s so much more here than the greatest hits and I’m even having to skip over some of those just to keep this at a reasonable length. Unlike nearly every artist I’ll talk about on this podcast, I really don’t believe there’s a bad phase of Tom’s career. For instance, after “Faster Horses,” Tom got back in touch with his bluegrass roots on an album of covers and originals, called The Magnificent Music Machine. It really is magnificent. Listen to his cover of “Fox on the Run.”

Fought a Mighty Big Machine

In the late ’70s, Tom was offered a hosting job on Pop Goes the Country, a 30-minute country music variety show on TV. Despite telling interviewer Alanna Nash that he didn’t want to take the job, in 1980, he took the job, replacing Ralph Emery and staying with the show for three years. In 1982, Jim Varney, a.k.a. Ernest, was given his first real job doing characters and the title of the show was changed to Tom T’s Pop Goes the Country Club. The show was syndicated, the implications of which I’ll talk more about in a couple of weeks with Buck Owens & Don Rich, but, for right now, let’s just say it means a lot of people were watching. Everyone who tuned in usually saw Tom open the show with a song and, from there, it stuck to the typical comedy/country TV show format, only with much more screen time dedicated to musical performances than to anything else. You can still find some decent clips on YouTube. You can also find one of the commercials Tom did for Tyson chicken…

In 1982, still sticking with that banjo sound, Tom T. Hall and Earl Scruggs recorded Bob McDill’s “Song of the South.” Bobby Bare and Johnny Russell also had early versions of what would become one of Alabama’s greatest hits later in the decade.

Tom had published his first book in the mid-70s, called How I Write Songs, Why You Can, which was later reprinted as The Songwriter’s Handbook. I haven’t read that one but judging by the cover, which you should always do, a summary for all you songwriters may be contained in this quote, “In order to write songs, you have to be able to recognize what a song is. You have to recognize the importance of something that is entertaining, and you have to say what you want to say very briefly.”

In 2016, he told Peter Cooper that “songwriters aren’t good songwriters. People are good songwriters […] You sit down as a person and write a song. If you’ve written a song by the time you stand back up, you’re a songwriter. But the person comes first.”

In 1986, Tom essentially retired from being an entertainer, perhaps due to embarrassment from becoming a songwriter for two hours in 1984 to make “Return to Harper Valley” at Jeannie C. Riley’s request. Just kidding but that story is in the previous episode if you want it. There was another album of children’s songs in 1988 but no tour to support it. You’d see him on TV or in the paper every now and then, appearing on a special, presenting or receiving an award. He spent most of his time writing and releasing fiction (which is obviously very good); writing book reviews for our local paper, The Nashville Tennesseean; and simply enjoying life at home with family on Fox Hollow.

In 1996, Tom released an album that included a song called “Little Bitty,” which was a ridiculously big hit for Alan Jackson that same year. Although, Alan did something a little bitty different with the production. Lyrically, “Little Bitty” was totally unlike anything else on the radio at the time. People still bought CDs in the mid-90s and, if they liked a song a lot, they even looked at the liner notes to see who wrote it. Alan Jackson’s cover led to many younger people learning about Tom T. Hall for the first time. Tom wasn’t even really trying for a comeback. He was still writing great songs but also still not touring. In fact, we’re told he tried to completely retire from music but his wife, Miss Dixie, wasn’t having any of that.

Hardcore bluegrass fans are probably annoyed that I’ve gone this long without mentioning just how important Dixie Hall has been to the genre. To keep Tom from leaving music for good, Dixie had to start writing songs again with him. When she passed away in 2015, she left over 500 songs in her catalog. Like I said before, you’ll be hearing her name in future episodes.

It’s possible the final Tom T. Hall album was released in 2007. Though I have every confidence that, at over 80 years of age, he could put out a fine collection of original material if he wanted, listen to “Once Upon a Road” and I think you’ll agree: if Tom T. Hall Sings Miss Dixie & Tom T. is the last album he releases, it’s one hell of a note to go out on.

Thank you for listening to (and reading) Cocaine & Rhinestones. This and every other episode of the podcast is written and produced by me, Tyler Mahan Coe. You can find me on Facebook and Twitter at that name, if you’d like.

If you have any questions about the podcast or anything else in life, the final episode of the first season will be a Q & A session that you can take part in by sending an email to questions@cocaineandrhinestones.com. BONUS: Cocaine & Rhinestones Season 1 Q&A Episode!

Please share this episode of the podcast (or this blog post) with one person. Anyone interested in songwriting, on any level, should be interested in this, I would think.

This episode is supported by Goodbuy Girls. If you’re looking for a good buy in Nashville, well, Southern Living Magazine named Goodbuy Girls one of the ten best places in the south to buy boots. Shop in true Nashville style on racks that have dressed Margo Price, Elizabeth Cook, Shovels & Rope, Lady Gaga and many more rad individuals, artists and musicians. Goodbuy Girls offers a mix of what Nasty Gal calls “Western Cult, vintage and new.” Check out the website at goodbuygirlsnashville.com. Follow them on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Make sure to swing by the next time you’re in Nashville. Tell them Cocaine & Rhinestones sent you and they’ll give you 10% off your purchase.

Next week on the podcast its the first of two episodes on Buck Owens and Don Rich. It’s taking me two episodes to tell the story, so you can imagine there’s a lot there. It’s got a little bit of everything for everyone. The story has significant connections to at least four previous episodes of this podcast and sets up some other stuff for future episodes still left in the first season. I think it’s going to be a big one.

-TMC

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [linked, if available]:

- Garth Brooks – “Not Counting You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Lee – “Lookin’ for Love” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Olivia Newton-John – “Let Me Be There” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jim Reeves – “This Is It” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Elvis Presley – “I Forgot to Remember to Forget” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Pee Wee King & His Golden West Cowboys – “Tennessee Polka” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bob Wills – “Steel Guitar Rag” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Carter Family – “Keep on the Sunny Side” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Chris LeDoux – “Working Man’s Dollar” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tompall Glaser – “Texas Law Sez” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wynn Stewart – “Playboy” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom Petty – “The Last DJ” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Browns – “Three Bells” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Flat & Scruggs – “Martha White Self-Rising Flour” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jimmy C. Newman – “DJ for a Day” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dave Dudley – “Mad” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Wright – “Hello Vietnam” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “I Washed My Face in the Morning Dew” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jeannie C. Riley – “Harper Valley PTA” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dee Mullins – “The Continuing Story of Harper Valley PTA” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “Ballad of 40 Dollars” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “That’s How I Got to Memphis” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “Homecoming” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dave Dudley – “Truck Drivin’ Son-of-a-Gun” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dave Dudley – “I Got Lost” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “I’m Not Ready Yet” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “The Year That Clayton Delaney Died” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “Old Dogs, Children & Watermelon Wine” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “America the Ugly” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “I Love” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “That Song Is Driving Me Crazy” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “Country Is” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “I Care” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “Faster Horses” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “Fox on the Run” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Earl Scruggs & Tom T. Hall – “Song of the South” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “Little Bitty” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Alan Jackson – “Little Bitty” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom T. Hall – “Once upon a Road” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Excerpted Video

These may be removed from YouTube in the future (for any of a number of reasons) but, for now, here they are:

Commentary and Remaining Sources

Everyone always makes such a big deal out of how great a songwriter Tom T. Hall is that I thought it would be interesting to make a point of emphasizing how successful he was as an artist, while still getting the songwriter stuff in there.

There’s another butterfly effect tangent on Shelby Singleton, here, if you want it. Take Shelby out of the music business and it’s even more likely that “Harper Valley PTA” never would have happened in any timeline. Because Shelby’s ex-wife, Margie, had to move to Nashville with Shelby, get divorced and be at that radio party with her new husband to ask Tom to write her a specific type of song, which had him thinking about that specific type of song when he drove by that sign that had the word “Harpeth” on it, etc. It’s crazy.

I do like to think that Rex Allen later saw a picture of Tom T. Hall and recognized him as the guy who left that hotel room when Rex wouldn’t stop complaining about not being shown any material from a hit songwriter. Probably not but it’s funny to think about.

Tom T’s Pop Goes the Country Club was filmed at Opryland USA, so he apparently thought it was just the Grand Ole Opry that shouldn’t be made out there. And Tom didn’t only do commercials for Tyson chicken. You can find a ton of Tom T. Hall commercials on YouTube. I’ve even seen him joke about how many product endorsements he did.

I failed to mention this in the Liner Notes for the previous two “Harper Valley PTA” episodes but, obviously, the books I read for any individual episode of this little series should be considered a source for every episode in the series, even if that information isn’t explicitly used in that episode. I read all these things for all three of these episodes. All the things I read informed my understanding of the events for each episode.

Okay, here are my sources for this one.

There is, of course, the Tom T. Hall book, The Storyteller’s Nashville. Naturally, anyone who enjoyed this episode should own and enjoy that book.

Tom has a piece on writing “Harper Valley PTA” in one of those Chicken Soup for the Soul books, called Country Music: The Inspirational Stories Behind 101 of Your Favorite Country Songs.

There’s a book called Watermelon Wine: Remembering the Golden Years of Country Music, that’s by Frye Gaillard. It’s not about Tom T but he is talked about a lot in there, as you would expect, the title being one of his songs and everything. It’s a good read to place his work into context of other things that were happening around him. I’d recommend it.

The “Hank Cochran wrapped up in a rug on a pool table” story came from a book called Tales from Country Music by Gerry Wood. It’s not a wonderfully written book but if you like stories like that then you’ll probably like it.

George Jones’ autobiography is called I Lived to Tell It All. There’s a lot that doesn’t get talked about in there and a lot that does. It’s worth reading, for sure. Like I said, that’s where I got the story of Tom playing poker with George and Wynn Stewart. By the way, kids, probably don’t play poker with someone if their first name is Wynn. You know, just an idea.

I was not making a wild inference when I said that Tom didn’t smash his guitars out of anger. He says as much in that interview with Alanna Nash in her book Behind Closed Doors.

Now, I need to clarify something about this show (and maybe about myself) that, based on some emails I’ve received, is being misunderstood.

When I make an episode of this podcast, my ultimate goal is to put you in the time and place of the main artist I’m talking about. Whether that’s by showing you things from that artist’s perspective or the perspective of their fans and critics who want something different than what that artist is giving them, the perspective of historical context by examining world events or the perspective of the conversation around mainstream country music during the time of that artist’s work – taking on any of these perspectives requires me, the writer and host of this show, to assume a voice that may or may not represent my personal feelings on whatever is being discussed.

Let me just give you an example of what I’m saying. When I talk to you about The Louvin Brothers, whose career was totally derailed by Nashville’s attitude towards traditional country music in the 1950s, the things I say about The Nashville Sound are not going to be very complimentary. Next week, when I start talking to you about Buck Owens, the things I say about the Nashville establishment in general are going to sound quite nasty. These are not necessarily my personal beliefs. In a few weeks, when I tell you about The Judds, some people are going to hear that episode and think I’m calling fans who want to hear “real country music” on their radios a bunch of whiners. And that’s not what I’m doing, either. All I’m doing is telling you a story, one little piece at a time, the only way I know how.

I see why the confusion is there because you’re just listening to me talk (or reading the words I write) but, if you must know, some of my favorite country music artists jumped headfirst into The Nashville Sound, making some of the greatest music of their careers in doing so. You can’t love Patsy Cline’s music and hate The Nashville Sound. You can’t be a George Jones fan and hate The Nashville Sound. (And, please, don’t write me to say that George Jones didn’t use The Nashville Sound because he was “countrypolitan.” That is a ridiculous, made up word for people who talked too much shit about The Nashville Sound and then had to think of something else to call it after they realized they liked a lot of it. It’s the same thing.

For the record, I like most of the songs I used (and referenced) in the intro of this episode during the “ruined country radio” segment. If you think that segment was about me trashing all those artists then you totally missed the point I was making. Conversely, I really do think Luke Bryan’s music is trash. So, you see, sometimes what I’m saying is what I, Tyler Mahan Coe, personally believe and sometimes it’s not. You probably shouldn’t spend any time worrying about it, though, because the only reason I’m saying it is to make the story work. What music I do or don’t like definitely does not affect how this show gets made.

The only agenda I have with this podcast is to attempt to document a little slice of history in each episode. I know that’s going to be misunderstood by some percentage of listeners no matter what I say or do. I knew that before I even got started. But I do have the option of leaving these words here for those with eyes to read them and that’s what I’m doing now.

And I know I told you in the liner notes of the “Okie from Muskogee” episode that my personal opinions will inevitably factor into the content of this show. That was me being honest with myself and with you about human nature. That wasn’t me telling you that I’m constructing false narratives to build a version of history that I want to be true. My aim is objectivity. It seems impossible that anyone could ever understand how important it is to me to try and get these stories right but let me just say that I know what it’s like for someone to get your story wrong. I know exactly what that’s like. I would never knowingly do that to another person – celebrity or not, living or dead, doesn’t matter – and the thought that I might do it on accident does actually keep me awake some nights.

Drinks with Tom T. Hall – American Songwriter

In the Words of Tom T. Hall – CMT.com

Nov. 1973 issue of Texas Monthly

Dixie Hall, prolific bluegrass songwriter dies at 80 – Tennessean