The story of a little independent record label in Texas becoming “a force” in the Nashville country music industry brings an outsider’s perspective to the anatomy of a machine. Going from backwoods honky tonks and roadhouse jukeboxes to stretch limos and private planes takes a lot of crooked deals and shameless hustle. When confronted by a powerful enemy, you’ll do whatever it takes to survive the turbulent rock and roll. When the whole world acquires a taste for your strain of Kentucky bluegrass, you’ll rake in the green. When they get their ears on for truckin’ songs, you’ll put the hammer down and stand on it. But don’t let the stars get in your eyes, because this story only ever ends one way.

Contents (Click/Tap to Scroll)

- Primary Sources – books, documentaries, etc.

- Transcript of Episode – for the readers

- Liner Notes – list of featured music, online sources, further commentary

Primary Sources

In addition to The Main Library and the Season 2 Library, these books were used for this episode:

Transcript of Episode

As part of my agreement with Simon & Schuster to publish a book adaptation of Season 2, the transcripts that have been freely available for over a year will be temporarily removed from this website. Please consider ordering a copy of Cocaine & Rhinestones: A History of George Jones and Tammy Wynette through your favorite local bookstore or requesting that your local library order a copy you can check out.

Liner Notes

Excerpted Music

This episode featured excerpts from the following songs, in this order [with links to purchase or stream where available]:

- Red Foley – “Pinball Boogie” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Hank Locklin – “Pinball Millionaire” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Lonnie Irving – “Pinball Machine” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Webb Pierce – “Heebie Jeebie Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Hank Lockin – “The Song of the Whispering Leaves” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Lefty Frizzell – “If You’ve Got the Money (I’ve Got the Time)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Arlie Duff – “Y’all Come” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bing Crosby – “Y’all Come” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “For Sale or For Lease” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “If You Were Mine” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Play It Cool, Man, Play It Cool” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “You’re in My Heart” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “No Money in This Deal” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Sonny Burns – “A Place for Girls Like You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Arlie Duff – “Back to the Country” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones & Sonny Burns – “Heartbroken Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Red Hayes – “A Satisfied Mind” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jean Shepard – “A Satisfied Mind” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Red Foley – “A Satisfied Mind” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Porter Wagoner – “A Satisfied Mind” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “What’s Wrong with You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Painless Heart” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Roy Acuff – “Is It Love or Is It Lies?” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “What Am I Worth” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Why Baby Why” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Seasons of My Heart” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jimmy C. Newman – “Seasons of My Heart” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Cash – “Seasons of My Heart” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Webb Pierce & Red Sovine – “Why Baby Why” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones & unknown artist – “Running Wild” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Elvis Presley – “Heartbreak Hotel” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Heartbreak Hotel” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “How Come It” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Glenn Barber – “Ice Water” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Sonny Fisher – “Pink and Black” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Glenn Barber – “Shadow My Baby” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Elvis Presley – “Teddy Bear” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jerry Lee Lewis – “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Everly Bros. – “Wake Up Little Susie” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ray Price – “I’ll Be There When You Get Lonely” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ray Price – “My Shoes Keep Walking Back to You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Ray Price – “City Lights” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- George Jones – “Just One More” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Benny Barnes – “Poor Man’s Riches” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Wayne Raney – “We Need a Whole Lot More of Jesus (And a Lot Less Rock and Roll)” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Willie Nelson – “No Place for Me” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Slim Willet – “Don’t Let the Stars Get in Your Eyes” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Perry Como – “Don’t Let the Stars Get in Your Eyes” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Goldie Hill – “I Let the Stars Get in My Eyes” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tommy Hill – “Oil on My Land” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Frankie Miller – “Blackland Farmer” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Stanley Bros. – “Rank Stranger” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bill Clifton – “Moonshiner” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Charlie Monroe – “Down in the Willow Garden” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Buzz Busby – “Lonesome Wind” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bashful Brother Oswald – “Black Smoke” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Kingston Trio – “Tom Dooley” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Grayson & Whitter – “Tom Dooley” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Henry Whitter – “Lonesome Road Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Johnny Bond – “Ten Little Bottles” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Guy Mitchell – “My Heart Cries for You” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Guy Mitchell – “Singing the Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Guy Mitchell – “Heartaches by the Number” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Guy Mitchell – “Traveling Shoes” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Glen Campbell – “For the Love of a Woman” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Jimmy Simpson – “Alcan Run” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Tom O’Neal – “Sleeper Cab Blues” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Dave Dudley – “Six Days on the Road” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Bobby Sykes – “Diesel Smoke, Dangerous Curves” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Doye O’Dell – “Diesel Smoke, Dangerous Curves” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Sons of the Pioneers – “Diesel Smoke, Dangerous Curves” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Burl Ives – “Diesel Smoke, Dangerous Curves” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- The Willis Bros. – “Give Me 40 Acres to Turn This Rig Around” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Red Sovine – “Giddy Up Go” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Red Sovine – “Phantom 309” [Amazon / Apple Music]

- Red Sovine – “Teddy Bear” [Amazon / Apple Music]

Excerpted Video

These videos were excerpted in the episode. For any number of reasons, YouTube may remove them in the future but here they are for now:

Commentary and Remaining Sources

The pinball machine sounds in the beginning were from Joker Poker, one of my favorite classic tables. The clip of the mobsters intimidating a soda shop owner about installing some pin games was from an old movie called Bullets or Ballots. And, of course, that clip of Fiorello LaGuardia was just some speech that he gave in which he happened to use the word “machine” and I thought that’d be cool to use. I did read a book called Pinball Wizards by Adam Ruben and some of the info came from there but that book is not really anything like what I did with this intro. There’s a little history but it’s mostly about how the author gets addicted to pinball and gets into competitive play. Really, I didn’t need much of a source for this intro because I’ve been playing pinball my whole life. For all the reasons mentioned, it seems like there were always machines around in the kind of places where I grew up. So a lot of my awareness of the history of pinball just comes from a lifetime of talking to other people who play it. And I did all my usual fact-checking before saying any of those things, using many sources readily available to anyone who runs a quick internet search.

It didn’t really make sense to use a clip of it but if it’s been bothering anyone trying to figure out where they’ve heard Lonnie Irving’s “Pinball Machine” before there’s a chance you heard a recording of The Fall covering it live, as Mark E. Smith was a big fan.

Red Sovine’s “Teddy Bear” is so objectively terrible that I didn’t want to end an episode full of mostly great music by bumming everyone out but if the way I talk about “Teddy Bear” seems excessively harsh in the context of the clip you heard, go ahead and listen to the whole song to have your day ruined.

On the topic of soundalikes, another way labels tried to confuse fans from being able to identify who they were hearing was by using the same pseudonym for multiple singers. So George Jones had soundalikes issued under the names Hank Smith and Thumper Jones but so did Leon Payne. There’s one side of a Dixie EP that has George Jones doing “Heartbreak Hotel” and Leon Payne doing “Folsom Prison Blues” – both credited to Thumper Jones – along with the “original hit recording” of “Seasons of My Heart,” credited to George Jones. Oh, and that soundalike of The Louvin Brothers’ hit with “Running Wild” was, of course, sung by an uncredited George Jones and some other unknown vocalist.

The song “Why Baby Why” was also recorded by Hank Locklin in 1956 and he also had a Top 10 hit with it. Then, almost 30 years later, Charley Pride took it to #1 again, so I’d say that’s a pretty great country song.

I couldn’t find out enough about what happened to bring this up in the main episode but Bill Starnes, Jack’s son who engineered Starday’s recording sessions when he was just a teenager, apparently robbed a bank in late 1956 and this somehow led to his mother Neva being arrested. If anyone out there knows anything more about this, I would definitely appreciate any information because nothing about it makes much sense to me and I’d love to know what really happened there.

Music publishing is a pretty confusing thing to a lot of people so I wanted to specify that Don Pierce walked away from the Starday split with 50% of the publisher’s share of George Jones compositions. It was only after listening that I realized some people could misunderstand what I said to mean Don took money that would’ve otherwise gone to George Jones, which was not the case. And the reason I could see some people hearing it that way is Don Pierce is another one of those music industry guys who has a reputation for being pretty ruthless in his business dealings…

There’s a story about Frankie Miller’s “Blackland Farmer” being signed over to Don Pierce in a way some people feel is unethical. I have not looked into Frankie Miller as deeply as others, specifically Jimmie McDonough, but I have seen Frankie Miller allude to whatever deal he made with Don Pierce and Frankie himself doesn’t seem to believe he was taken advantage of. Don Pierce was absolutely a business-minded, budget-conscious hustler but I do feel it’s important to draw a distinction between characters like him and characters like his old boss, Bill McCall at 4 Star. Looking back on this industry, there will always be outdated practices and philosophies which seem predatory from a modern perspective but were accepted at the time. That’s different from people engaging in behavior that was viewed as unethical even at the time they were doing it. Most of the stories people tell about getting mad at Bill McCall end with them staying mad at Bill McCall. Most stories people tell about getting mad at Don Pierce end with them not being mad at him anymore, either because Don made it right or because, at the end of the day, you just had to accept and laugh about where his priorities were.

There’s a pretty great story in a 1965 issue of The Tennesseean newspaper where an unnamed musician says Don Pierce invited a bunch of industry people out to a lake in the Nashville area for a BBQ. Everyone gets out there, the grill’s goin’, people are drinking beer… Someone eventually says something to Don about how nice it is to be out there by the lake and Don mentions they just so happen to be hanging out near some lots of land he owns and is trying to sell. So, if they’d like to have a reason to come out to the lake more often, then maybe they should talk business. That’s just Don Pierce.

Okay, Season 2 uses information from the same group of reference books I’ve collected on The Library page of the Cocaine & Rhinestones website in order to not have to talk about the same 15 or so books in every episode’s Liner Notes. However, there is also going to be a separate Season 2 Library page on the website for the same reason. Those of you who want to avoid spoilers for the entire season should probably steer clear of that Season 2 Library page until you’ve read another four or five episodes but I will be discussing my sources from that page as they become relevant in the Liner Notes of each episode.

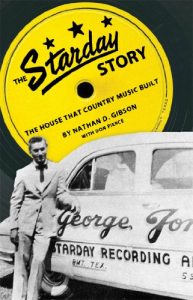

Naturally, one of my main sources for this episode was a book I mentioned last season, titled The Starday Story: The House That Country Music Built, by Nathan D. Gibson. My opinion of this book has not changed. It is still a phenomenal resource. As much information was in this episode, there’s still so much more in that book for anyone interested in the history of Starday. This label existed for decades. There are Starday artists and many stories I didn’t even mention. For example, a guy named Peck Touchton had his only song released on Starday accidentally placed on the mislabeled b-side of a George Jones single. Apparently Jack Starnes tried to warn Don Pierce about the mistake in a letter but, due to some kind of car accident, the letter didn’t make it to Don in time. There are dozens more pieces like this in Nathan’s book. If you liked a lot of the clips in this episode, there were quite a few more songs on the list of things I thought I may possibly use and Nathan’s book is really one of those where you’re gonna want to take it, sit down on YouTube and just listen to all the songs he mentions. You’re probably gonna find something you haven’t heard before that you really like.

The other primary source for this episode is the Bear Family box set of George Jones’ Complete Starday and Mercury Recordings. George Jones is the biggest artist who was associated with Starday for the longest period of time, so a lot of people who write about his Starday years will often throw in little tidbits of info that become relevant to other artists or musicians who were involved. There are a lot of times where that stuff completes pieces of a puzzle I’ve been trying to put together. Bear Family box sets usually come with pretty informative booklets but this one comes with an actual hardcover book by Kevin Coffey and this book was a truly great resource. Even just the data on George Jones’ recording sessions in the back of the book was something I went back to dozens of times to make sure about the dates things happened and which people were involved but there were also many little facts about other artists which plugged right into other threads I wanted to follow. Kevin’s book from that box set definitely made this episode easier to put together.

As mentioned, Neil Rosenberg’s book Bluegrass: A History was one of my main sources for the bluegrass segment and is the definitive work on the genre. If you enjoyed the clips during that segment or the stories about bluegrass becoming a huge fad, that book is highly recommended reading material. As always, there is so much more to the story. Neil’s book will continue to be a source frequently used on this podcast.

Lastly, one of the reasons Season 2 took longer than I expected and became larger than I expected is because I was invited to research in the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s archives. This is not a thing I knew existed when I made Season 1 of the show. The volume and quality of information available in those archives is far beyond anything I could have expected. However many hours I spent in there taking notes as quickly as I could before closing time, it took probably ten times as many hours at home to unpack those notes, research the additional avenues they opened up and plug everything in to the stories I’m trying to tell. As such, there’s really no way for me to distinguish between information which should and shouldn’t be attributed to the time I spent in those archives. While this podcast is not officially associated or partnered with the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, it’s only right for me to mention them as a source for every episode going forward. If you’ve never been to the museum, please do visit them when you come to Nashville. If you are a writer or researcher, I cannot stress how important it is for you to use those archives.

Okay, that’s it. Get ready for Owen Bradley because telling his story requires upending a huge portion of the written history on the entire genre of country music. Long story short, I’m about to start a whole lot of arguments everyone should have had quite some time ago.